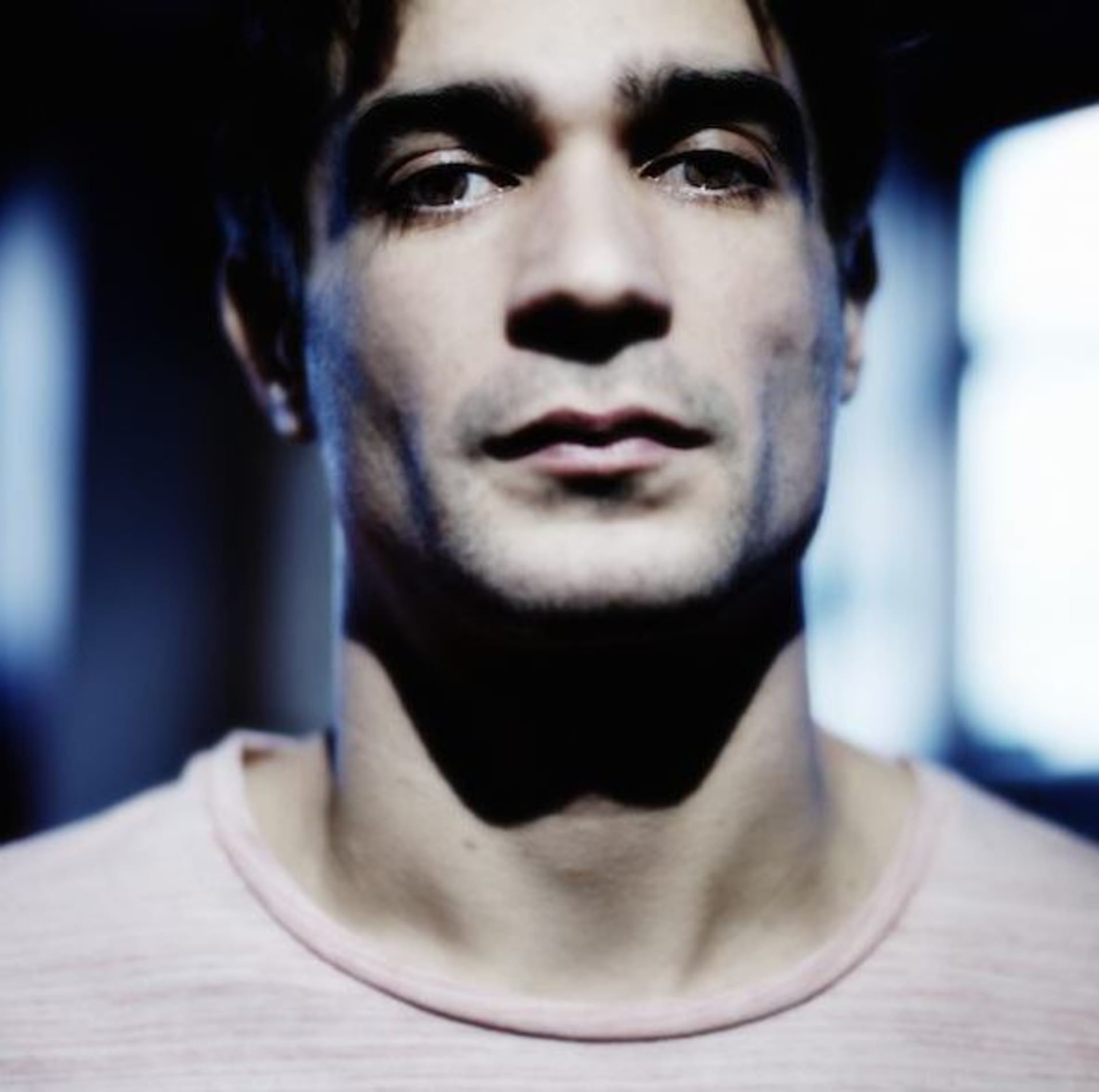

“Brian Eno liked Immunity a lot” – Jon Hopkins interviewed

A year on from the release of his critically acclaimed fourth LP Immunity, we caught up with producer Jon Hopkins backstage at the EB Festival Cologne to talk autogenic training, comedowns and Coldplay.

In 2013, Jon Hopkins finally enjoyed solo success that was a long time coming. His debut album, 1999’s Opalescent, caught the wave for slick chill out room ambience—and, strangely, the ears of Sex and the City’s music supervisors. However, his career stalled when his follow-up LP was roundly ignored by the music press. What followed was a decade spent honing a polymathic approach to music, notching up film scores (including the soundtrack to Brit film Monsters), credible collaborations (2010’s Mercury-nominated Diamond Mine with King Creosote) and production work for stadium behemoths Coldplay. When Immunity dropped in early summer last year, its combination of minor key melancholy and abrasive techno headcleaners made it the break-out electronic album of the year. The few non-converts found their resistance weakening when faced with Hopkins’ intense live shows—exemplified by his closing set at EB Festival Cologne. There, we sat down with the celebrated producer backstage to pause and reflect on the year since the release of Immunity.

Jon, I’m really intrigued by your interest in self-hypnosis and autogenic training. Could you tell me a bit about that?

I started doing it about thirteen years ago, when I was about twenty-one. Self-hypnosis is a technique that has a similar goal to meditation: calming yourself down to a point where you can be entirely in the moment. I noticed that music tends to come quite clearly when you’re in that mindset, it just kind of quietens the noise of everyday life. At that time it was really just a therapeutic thing because I wasn’t dealing very well with life as a broke musician; a twenty-year-old not knowing what to do, trying to write an album but not knowing who was going to do it.

That’s an intense challenge for a twenty year old. By that point your debut had come out right?

It came out when I was twenty-one but it was written when I was nineteen and then I sort of fiddled around with it for a bit whilst I was still working as a session musician for a pop producer guy. That made me quite, well, it wasn’t really my kind of thing. He was a lovely guy and really good songwriter, but it was depressing work really.

Why was it depressing?

I’m not a keyboard player for S Club 7, that’s why, and that was the kind of stuff he was pitching. I respect that kind of writing as a skill, but it required me to be a kind of “on cue” keyboard player. Like: “Can you do this style today or that style today?” I can’t really do that. I occasionally could bend things to make it work but there was a lot of conflict between us because I’m not really a natural session player, I’m too much of a musical megalomaniac. I’m more built to be in charge of the productions I’m involved in.

It’s interesting you say that self-hypnosis and autogenetic training quieten down the brain because now, more than ever, our attention are constantly under siege from competing distractions. Do you want to challenge this development?

I want to challenge it, that’s why my songs are reaching ever-longer lengths. I want to do the opposite of providing instant hits. Not hit music, but an instant hit. I don’t want to be a “one listen thing”. I want to create music as a place to exist in for a period of time, or a story, rather than just an immediate sensation.

You mention avoiding the idea of the instant hit—a drug reference right there—and this is detectable in the structure of the record: going out, coming up, coming down. And certainly as much attention is given to the coming down part . . .

More so actually. I find it to be the more emotionally resonant bit of the experience. I guess it’s inspired by some life events, some really long parties, kind of two day parties, where you push it to the absolute limit and you bond with people in an extraordinary way. It’s almost a year of friendship in one night. I’ve had these crazy nights, I went through a phase of really pushing that. And the album wasn’t really started until after that. Because you can’t write when you are doing that but it is maybe something you need to go through once in your life. And I found there is this really melancholy and beautiful element when that feeling finally leaves you. Before you hit the empty few days after. There is the magical bit where you are gently still feeling something.

What parties were you going to?

I’m not really into clubbing so I guess most of these were just at houses of really good friends. Everyone playing everyone all their favorite music and all kinds of emotions going on—no sleep at all. These things sometimes get triviliazied in some way, people say they aren’t real. But it is a very real experience and maybe people who haven’t experienced that don’t understand how profound it can be to go through.

Of course, the memories of those experiences are as real as any other.

It’s totally real. Reality is only perception anyway, if you feel like something, then that is what is happening. The important thing is to be with the right people, because that’s what makes it genuine. We all had nights where you were with a bunch of random people who you realise later on you don’t like. Where you realise when you are back at some random house and go “Who are these people and why am I here?”. That’s not so good.

When you look back and cringe?

Of course. It’s not those ones so much that I am thinking about though. But these days I don’t really party like that at all, but I have enough in my memory. Also, something I found out is that through these experiences, and through meditation and various forms of yoga, is that they all have the same ultimate goal: to be entirely present but also to be open to that feeling of being in a trance and letting things just wash over you and just existing within a period. And that’s when music and sounds are at the best they can possibly sound. The track “Sun Harmonics” is written specifically for the very end of one of those experiences, like midday—or whatever time you finish—really just because I wanted to hear it myself. A lot of music you write because you want to hear it and no-one else has written it.

After the release of your second album you kind of went behind the scenes for a few years. Now that Immunity has been so successful, does it feel strange suddenly having attention directed back onto you?

Basically if the second album had done well, I would have been doing all that ten years ago. And in fact, as a slightly arrogant young man, I kind of assumed it was going to do big things because I was really proud of it and, you know, spent a year on it. I thought “Am I ready for this? This is going to be so exciting!” and then literally nothing happened at all. And it had tunes on it that were so strong and it had no attention, no reviews or anything. That was quite a massive learning experience and kind of difficult experience to go through. But had that not happened I would not have learned how to work with vocalists and learnt how to do film scores and do all the collaborations that I did. And I was never going to leave solo music alone forever, I just left it alone for a few years. I started writing again slowly by 2006, piecing things together again and by 2008 there was another album ready. Again that one made some inroads and then finally this one, the last one, capitalized on everything that had happened.

Why do you think that second album didn’t land?

Listening to it now, it’s just because it’s really pristine and polite. I thought it was quite edgy then but I just wasn’t listening to much stuff. I wasn’t aware of how much further people were pushing things sonically. I think melodically it has a lot of strength and I would almost like to rework some of those tracks some day although I will probably never get round to doing that. But there is a few tracks in there which can potentially be really big dancefloor tracks but it’s just sonically so pristine and perfect sounding, and not in a very good way, I just don’t think it had any edge.

Do you listen back to your first album at all?

Quite rarely. There are a few tracks on there that I will always like but anything that has drums in I can’t really listen to. It’s just cringeworthy. You know, those beats were done in 1999 and if I was to still think they were good now then I wouldn’t have changed style at all. It’s important to write off your past. But melodically some of it I love. Some of the atmospheres are really nice.

You went on tour with Coldplay. When I spoke to Joe Mount from Metronomy, who also supported Coldplay, he said that there was no one in the audience for them. Did you find it tough?

I had a huge amount of respect for Coldplay for having a complete unknown, because this was even before Insides came out. The music from Insides was a lot edgier in terms of rhythm and weirder than the Immunity stuff. The animations I had with it were completely warped. But it was the only way I could do something that excited me and I didn’t want to re-hash the second album, I wanted to do something really weird. It was almost like a film, a multimedia experience . . . But yeah I didn’t often enjoy the shows because playing to twenty thousand people, you might engage about a hundred of them. Which is still a good amount of people—if you do thirty shows like that then you still got three thousand new fans. But the ratio was not great. If they had a band like Elbow support them instead, people would have flocked to them. But I admire them for being daring like that. I think Chris thought I had more of a live profile than I actually had. It was actually my first tour though.

Oh no. Didn’t they know that?

No, I didn’t mention it. They asked if I wanted to open and I just said yes, because you can’t really say no can you?! He saw a little video, I was doing like maybe one or two shows a year, and he thought it was great. He probably thought “Ok, he can do this”. He thought I was much bigger than I was.

So actually playing must have been really nerve wracking.

Beyond that, really, almost funny. The first show was Brixton Academy, which was a rehearsal show in front of an audience. Four thousand is considered small for them. That was alright, but the next one was Madison Square Gardens, which was twenty thousand people. I was actually laughing while I was playing because I thought, “What the hell is going on here?” It was hilarious. People thought it meant that I was having a great time. I was having a great time! I drank a lot of vodka before the show. Occasionally, when we played in the less obvious places like Salt Lake City or Kansas, where I was expecting to get the worst response, I actually got the best reponse. People that never had seen or heard this kind of thing, the younger crowd were really excited by it. And it was more places like New York or Montreal or Chicago where they didn’t really register. It was weird, you couldn’t really guess where it would go.

You worked with Brian Eno on producing Coldplay. Do you know what record of yours Eno heard where he decided he wanted to hook up with you?

There wasn’t one. There was a mutual collaborator, Leo Abrahams, who is a really old friend of mine and who I had jammed with for years. He met Brian and they made a lot music by improvisation together. And Brian asked if there was anyone else he wanted to invite to join the jam sessions, because he wanted to make Another Day On Earth at the time, and Leo invited me. He actually didn’t listen to my solo music for years, he wasn’t really interested. But he’s just not that kind of listener, I don’t think he explores that many albums by random young artists. But he liked Immunity a lot, he responded really well to that.

What did he say?

Well, his way of telling me that he liked it was that he wrote me an email telling me he had gotten into conversation with a psychologist at a hospital who’d had a lot of success playing it to psychologically ill people. He was trying to explain how it had a lot of therapeutic effects.

How did you feel about that?

Brilliant!

That’s incredible and returns to the idea about creating music for people to exist in. What did he say exactly?

I can’t remember exactly how he phrased it, I should dig out the email really. What’s been weird about it is that I had responses from a really wide cross-section of people. I get really nice messages through my website or whereever from people who found it helpful through some difficult time. Which is always an honor, people saying that. ~

Published June 30, 2014. Words by Louise Brailey.