Danceteria: Where Studio 54 Met CBGB In 1980s New York

Danceteria sent shockwaves through the city’s party scene when it opened in May 1980, all the way down to the Mudd Club, where its owners had spent a fair amount of time hanging out. Dedicating the basement to DJing, the first floor to live bands and the second floor to video, the venue presented revelers with a novel element of choice—not because of the range of entertainment, but because all of the options were available at once. The shift to sensory overload was unmistakable as two bands appeared live every night, two DJs shared the turntables, and experimental filmmakers curated showings within a groundbreaking video lounge. In isolation, each floor oozed with the alternative inventiveness of downtown. Taken together, they offered a level of explorative creativity that threatened to dwarf the offerings of Club 57 and the Mudd Club. Yet in contrast to both of those spots, Danceteria was located not in downtown but midtown, toward the Eighth Avenue end of 37th Street, where commerce ruled the streets. With Jim Fouratt and Rudolf Piper at the helm, the mongrel explorations of the Lower Manhattan party scene were set to storm the city center.

Raised in a working-class Irish Catholic family, Fouratt moved from Rhode Island to New York in 1961 to study with Method acting pioneer Lee Strasberg, whose insistence that he be true to himself persuaded Fouratt to accept his homosexuality. Radicalized several years later when a judge ruled against him for his behavior at an antiwar demonstration, Fouratt cofounded the Youth International Party (or the Yippies) and a little later the Gay Liberation Front, having witnessed the early flash points of the Stonewall rebellion. To relax, he headed to Max’s, CBGB and Studio 54, although he rarely told his comrades about his trips to the midtown venue. Then, in the summer of 1978, a friend took him to Hurrah, a onetime fashion-conscious club located at 62nd Street that rebranded itself as the city’s first rock discotheque after Studio 54 stole its crowd. Introduced to the owners, Fouratt told them how he thought the spot could be improved. In early 1979, or thereabouts, he landed the task of reviving it.

An occasional visitor to the Mudd Club, which he thought of as being rooted in the social interaction of its customers rather than its entertainment offering, Fouratt hired the White Street alternate Sean Cassette to work as his DJ, oversaw the installation of video screens above the dance floor, and booked punk and new wave bands such as Gang Of Four, Pylon, the Rotating Power Tools and Ultravox. “Disco was something we were moving away from,” he observes. “I wanted to fuse Hurrah with a downtown sensibility that was very art-driven. I wanted to book the same kind of art-damaged acts that would play CBGB.” Yet the promoter also distanced his venue from the leather-jacket roughness of the Bowery venue by introducing the fashion-conscious “See And Be Scene” slogan as well as a door policy that required groups of young men to wait while gay men were let in, only for his run to end the night the owners demanded he pay Klaus Nomi less money, even though 700 people had packed the club. Fouratt stormed out of the venue, but he regretted his decision the following morning, by which time the owners had placed a padlock on his office.

As for Fouratt’s soon-to-be business partner, the West German-raised Piper made his fortune working as a stockbroker and then running a restaurant business in Brazil before he decided to open a club in New York. (He was smoking a joint and enjoying the company of women on an Ipaneman beach at the time of the decision.) “There was Studio 54, which was the greatest in the world, and Xenon and Hurrah, but as a place, midtown was lame,” he concluded soon after arriving in the city. “Downtown there was just the Mudd Club, which was far too spartan in its amenities and didn’t have a good layout, and CBGB, which was this piece of aesthetic shit. I thought, ‘Man, somebody’s going to have to do more than this.’ ”

Piper headed to the Mudd Club on a near nightly basis all the same, in part because it was “intellectually rewarding without being boring,” in part because it was the “perfect place” to get to know the “downtown celebrities of the day,” in part because it was the “best place to pick up chicks” (whom he took back to his room in the Chelsea Hotel with such regularity that nightlife commentator Stephen Saban published a piece in the SoHo News about his activities titled “German Sexual Response”). As the queues on White Street lengthened, Piper concluded that it would be perfectly viable to open an alternative spot, especially if it offered the artist community a place where they could show their art. “I loved the Mudd and it motivated and inspired me,” he confirms. “Ultimately, and now it can be told, I wanted to do a club that would be better than the Mudd!” Steve Mass recalls that Piper virtually lived in the Mudd Club. “He was very friendly, charming and suave,” notes the owner. “He had this kind of European playboy presence. I didn’t know he was going to start a place of his own.”

Careful not to blab that he was, as far as he was aware, the wealthiest person living downtown, Piper had the power to “make things happen” and purchased a three-story building on Crosby Street in SoHo. He planned for “basement activity” in the basement, dancing on the first floor, and a gallery for local artists on the second, because the SoHo galleries “were never interested in the downtown scene,” only to face concerted opposition from artists and the community board to his plans. At that point Cassette introduced the hyper-articulate Fouratt to Piper on the basis that the ex-Hurrah promoter could talk the project out of trouble, and the three of them held brainstorming sessions in Fouratt’s office on Waverly Place, “where the whole concept came together,” recalls Piper. Fouratt made good progress until Piper’s building contractor threatened one of the protestors, after which negotiations broke down.

Naming his venue Pravda after he stumbled across the reference in File and Wet magazines, Piper opened all the same. “It was one of the most fabulous nights in the city,” the owner claims of the launch, which took place on Thursday, 8 November 1979 and featured a fashion show by Betsey Johnson. “Absolutely everybody in town was there. It was the beginning of this bizarre new style.” The party brought together Bauhaus, the iconography of David Bowie’s Heroes, Soviet aesthetics and postmodern irony. “There were a lot more fashion people, a lot more trendy people, a lot more uptown people than there were at the Mudd Club, and they were dressed in a new way,” recalls Leonard Abrams. “There were all these people who were meeting each other for the first time who were doing all these creative things. They were influenced by punk and were reinventing themselves, investing themselves for the first time in throwing out all these ideas. It created a big impression.” Chi Chi Valenti remembers the night captured the zeitgeist by being “almost Russian constructivist yet fetishy at the same time.”

Only the neighbors were underwhelmed and, having registered their unhappiness, city inspectors closed the spot the following day. Piper argued during subsequent negotiations that he wanted Pravda to operate as a venue for the local community, maintaining that SoHo could come to resemble bohemian Paris of the 1920s if it opened itself to pleasure. Distrustful, residents replied that he had lost control of the opening-night party and couldn’t be trusted to run a peaceable venue. “The neighbors wanted to keep SoHo as an exclusive artistic enclave,” reasons the German. “They were too fucking serious and did not understand the concept of uniting art and nightlife. But Pravda made my entire career in New York. The fact that it closed after one night added to the myth.”

Fouratt hit on the venue that would become Danceteria when he agreed to represent a group that was booked to play at Armageddon, a nightclub located on 37th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. When the venue’s Mafia manager told him at the end of the night that he couldn’t afford to pay the performers, pulling out a gun to demonstrate his sincerity, Fouratt offered to tell the manager how he could turn his club around if he settled. The manager paid up and asked Fouratt to take over the venue. “The first thing that Jim said is, ‘We can cut a deal as long as you guys stay away,’” recalls Piper of subsequent negotiations. “They honored their commitment, and that was important because downtown people don’t like the mob, because the mob were Guidos and dressed ridiculously.” Initially skeptical, Piper came round to the idea of opening in midtown after Fouratt took him on a tour of the streets that surrounded the venue, where garment manufacturers and trade retailers imbued the area with a gritty character.

The duo threw themselves into a collaboration that would leave an indelible mark on the era’s party scene. A trained architect, Piper introduced 1950s-style wallpaper, furniture and motifs as an “absurd joke” that mocked that decade’s “dream of finding happiness through domesticity and mindless consumerism,” and he also hired young artists, including Keith Haring, to cover the venue’s walls with xerox art. Fouratt oversaw the upgrade of the venue’s sound system as well as the construction of the second-floor video lounge, which he developed in conjunction with video artists Emily Armstrong and Pat Ivers, who had contributed a video installation called the “Rock and Roll Classroom” to the opening of Long Island City gallery PS1. Having vehemently objected to Piper’s suggestions of the Bunker and the Eagle’s Nest, both of which carried Nazi associations, Fouratt also came up with a name for the venue while walking in front of either a carpet store called Carpeteria (as Fouratt remembers it) or a cafeteria, probably Dubrow’s, a postwar eatery that sported a classic 1950s neon sign (as David King, a British graphic designer, musician and friend of Fouratt, recalls). “That’s it,” Fouratt exclaimed the moment it struck him that the club would present customers with a menu of options, like a cafeteria or the carpet store that played on the café concept. “Danceteria!”

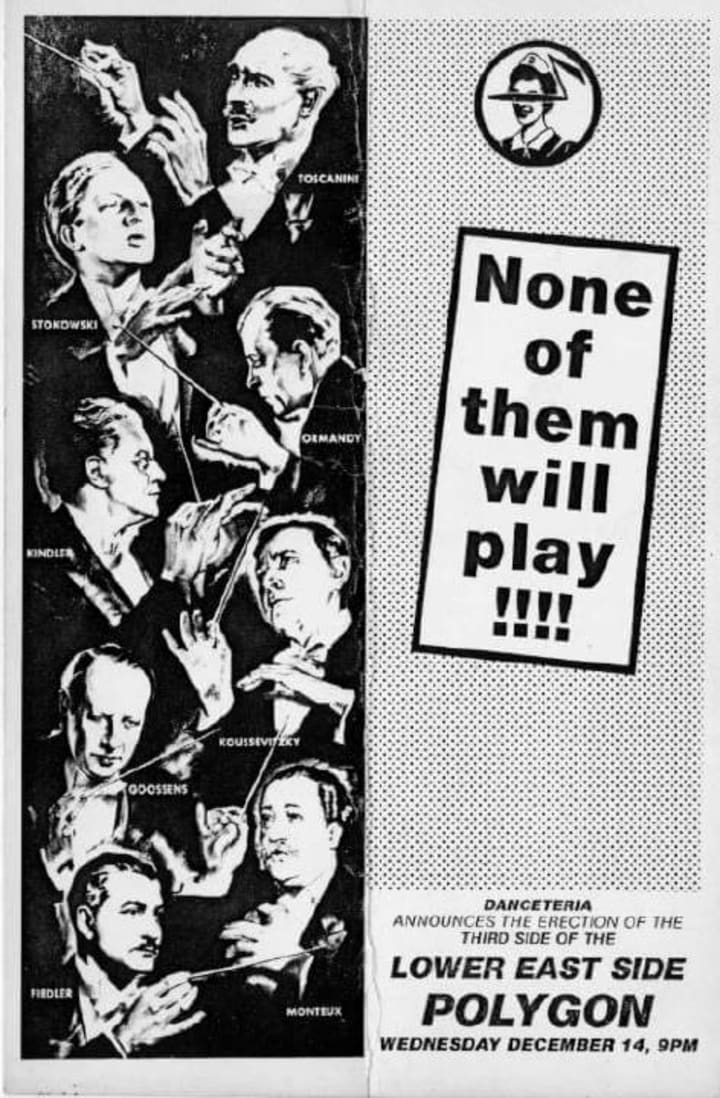

Running from 8:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m., the opening-night party of 9 May 1980 attracted a similar crowd to the one that gathered at Pravda. “We were apprehensive that the venue was outside of downtown’s holy land so we plastered posters all over town,” remembers Piper. “In the end we were jammed beyond belief. There was almost a mass hysteria.” With the sensational ephemerality of Pravda feeding the excitement, Fouratt introduced bands on the first floor, Armstrong and Ivers screened video footage recorded at CBGB plus other independent offerings on the second, and Mark Kamins joined Sean Cassette behind the turntables in the sweaty basement. “From the first night the mix of art, live music, video, fashion, staff and DJing was the formula,” notes Fouratt, who booked the bands and hired the DJs. “Hurrah was the incubator, but because it had one floor, it was limited to the linear moment. Having three floors on 37th Street changed everything. The DJs weren’t in competition with the bands and the video lounge. The floors offered a nonstop choice.” Even midtown had taken a leap into the hybrid unknown.

Regarding the dance floor, Fouratt had wanted to find someone to double up alongside Cassette on the basis that it would be tough for one DJ to play back-to-back 12-hour sets and more interesting to have two DJs share the turntables if the chemistry was good. Raised in midtown Manhattan on 49th Street and First Avenue, Kamins offered contrast, having met “all the gay DJs” while working in a record store before he finally landed a job working the lights and then the turntables at Trax, a 72nd Street discotheque that showcased live bands. “At the time you could go to a disco and hear four-on- the-floor all night,” notes Fouratt, who went to hear Kamins play at the spot following a tip-off from Nancy Jeffries, an A&R talent scout who had signed disco diva Evelyn “Champagne” King and new wave outfit Polyrock to RCA — precisely the kind of combination that he was after. The promoter concluded that Kamins was “much more sophisticated and eclectic” than most disco DJs and would strike “a good balance” with Cassette’s punk-oriented mindset. “I decided he was in touch with what I was trying to do aesthetically,” he says.

The DJs struck up a quick camaraderie, playing mini-sets of two or three records each. “We had no idea how it would work when it was suggested but we agreed to try,” recalls Cassette. “After the fourth spin, having played two records each, the bout started and we seemed to have something. We bounced off each other—it was a dialogue. The secret was we never tired of trying to outdo each other, so the energy came through.” The fact that they were hired to play for 12 hours encouraged the DJs to explore contrasts and correspondences as they juxtaposed Public Image Ltd (PiL) and Bohannon, Killing Joke and Donna Summer, while the fresh wave of recordings that started to layer punk sounds on top of a disco beat provided them with fresh common ground. “We could change the tempo but the vibe—the heart—would stay the same,” remarks Kamins. “The people that liked punk got into Bohannon and the people that were into my underground black music got into English punk and new wave because the vibe was the same.”

On the floor above, live bands combined the sophisticated with the popular. “I wanted to try and treat seriously the art that was being developed, but to do it in a non-serious environment that was closer to the mode of pop culture,” Fouratt notes of his curatorial approach. “I always used to introduce the acts and explain why I had booked them. I’m sure I was insufferable but I wanted to provide a window of understanding to the audience.” Devo, the Feelies, Gang Of Four, the Go-Go’s, Ministry, the Plastics, Polyrock, Tito Puente, Pylon, Sun Ra, the Raybeats, Pere Ubu and X played live. On one occasion Generation X lead vocalist Billy Idol jumped on stage during a solo performance by Alan Vega, a member of the punk-electronic duo Suicide, and they started to sing country and western songs. “People liked to pit the Mudd Club against Danceteria,” notes Fouratt. “The Mudd Club was hipper, the Mudd Club was downtown, whereas we were more populist and placed live performance at the core of the club. But I always thought of ourselves as doing the same thing. We spoke the same language aesthetically.”

Unconcerned by sub-rudimentary bathrooms, 2,000 punks, rockers, New Romantics, junkies, whores, sadomasochists, artists, Studio 54 exiles and ne’er-do-wells flocked to the venue every Friday and Saturday, prompting the East Village Eye to remark that the crowd “exhibits that Lower East Side aesthetic (stiletto heels, purple hair and pointy sunglasses).” It certainly began to seem as though downtown was more a “state of mind” or “an identification” than a geographical location, as Fouratt puts it, with the concentration of artists, musicians, performers, photographers and writers who worked at the 37th Street spot illustrative of the way a community and its way of life could shift almost seamlessly between different parts of the city as circumstances required.

“I think it spread word-of-mouth because most of the people who worked there were friends anyway,” comments writer, performer and poet Max Blagg, who joined a team that included Karen Finley, Keith Haring, Alexa Hunter, Zoe Leonard, David McDermott, Peter McGough, Haoui Montaug, Chuck Nanney, Michael Parker and David Wojnarowicz. “So many wildly talented people worked there.” Asked to remove his moustache if he wanted to remain employed, Fouratt having decreed that anyone with facial hair should be automatically turned away at the door, Kamins maintains that it was at Danceteria that he learned that a successful club had to have the “perfect mix” of staff. “The doorman mixes the people, the bartender mixes the drinks, the DJ mixes the music and all three mix the whole fucking cake,” comments the DJ.

Ignoring the blistering heat and lack of air conditioning, dancers partied as though their lives depended on it that summer. Fouratt and Piper held a special event for the Rolling Stones one night and premiered David Bowie’s “Ashes to Ashes” video on another. “Danceteria was very modern and current,” observes Brian Butterick, a Bronx-born drag queen who ended up joining the staff. Piper marvelled at the unfolding scene. “Objectively one cannot describe this, but Danceteria was one of the greatest places ever in terms of its energy,” he reminisces. “There was just something in the air.”

Yet his and Fouratt’s exhibitionist streak, readiness to take out ads in the New York Times and irreverent approach to selling unlicensed alcohol positioned Danceteria as a car crash waiting to happen, and both were absent when authorities raided the venue on October 4, arresting and charging Armstrong, Blagg, Butterick, Haring, Ivers, Montaug, Wojnarowicz and 14 others as they went about their business.

“The dance floor was an inch deep in pills and glassine envelopes,” remembers Blagg. “I was stupid enough not to get out from behind the bar in time and the cop who arrested me stole my tips, the lowdown scum.” Fouratt instructed his attorney to arrange for the employees to be released and headed to the local precinct to ameliorate the situation. “I felt really awful,” he recalls. Blagg notes that “the owners were no heroes,” however, while Armstrong recalls that Ivers was named as the venue’s manager at the eventual hearing. “Danceteria had absolutely no permits whatsoever—it was insane,” reasons Piper. “Then we got busted and we said, ‘OK, next!’”

The partners hit on a new spot after Fouratt went on a reconnaissance trip to G. G. Barnum’s Room, a transsexual-trapeze-disco-hustler bar located on West 45th Street that had recently lost its liquor license after a murder took place on its premises. Checking the basement, Fouratt discovered old signage for the Peppermint Lounge, the original home of the twist, and hurried to tell Piper they had to reopen the legendary spot. They struck a deal, rehired the 37th Street team, and launched in November. Fouratt maintained his edge, booking acts such as Black Flag, the Cramps, Gang Of Four, Philip Glass and X, and he also persuaded David Azarch to move over to the reopened spot.

Agitated that Steve Mass was handing Johnny Dynell and Anita Sarko more time behind the turntables, Azarch knew that the new setting could never match the “clientele chemistry” of the Mudd Club, and it didn’t. But the DJ also appreciated the eclecticism of the shows, the freedom he enjoyed in the booth, the records Fouratt passed his way and the tripling of his pay. “DJs such as David Azarch left me when they got offered much better deals or work by promoters who respected them and gave them a long leash to do what they wanted to do,” observes Mass.

Fouratt’s and Piper’s run at the Peppermint Lounge turned out to be a short one. Within weeks the management began to grumble about Fouratt’s outgoings, including the $100 fee the promoter offered to a performance artist who dressed in a diaper to lip-synch Bowie songs. As tensions mounted, the venue’s spotter—the employee tasked by the management to check that the bar staff weren’t skimming cash—offered to give Fouratt a lift downtown after the venue closed one night. “You know, I remember you from the Stonewall and you’re a good kid,” the spotter revealed in the car. “I’m going to have to kill you, but I just want you to know it’s nothing personal.” Fouratt opened the door and rolled out of the moving vehicle as it revved down the West Side Highway. Initially skeptical about Fouratt’s account, Piper grasped the severity of the situation when a manager sent him tumbling down a set of stairs the next time he visited the spot.

The promoters responded by putting an ad in the Village Voice. “Jim and Rudolf have left the Peppermint Lounge,” it ran. “We will tell you where the new place is. The beat goes on.” OK, next.

Copyright Duke University Press 2016. You can purchase ‘Life And Death On the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983’ here.

Published September 27, 2016.