Hans Ulrich Obrist visits Ai Weiwei

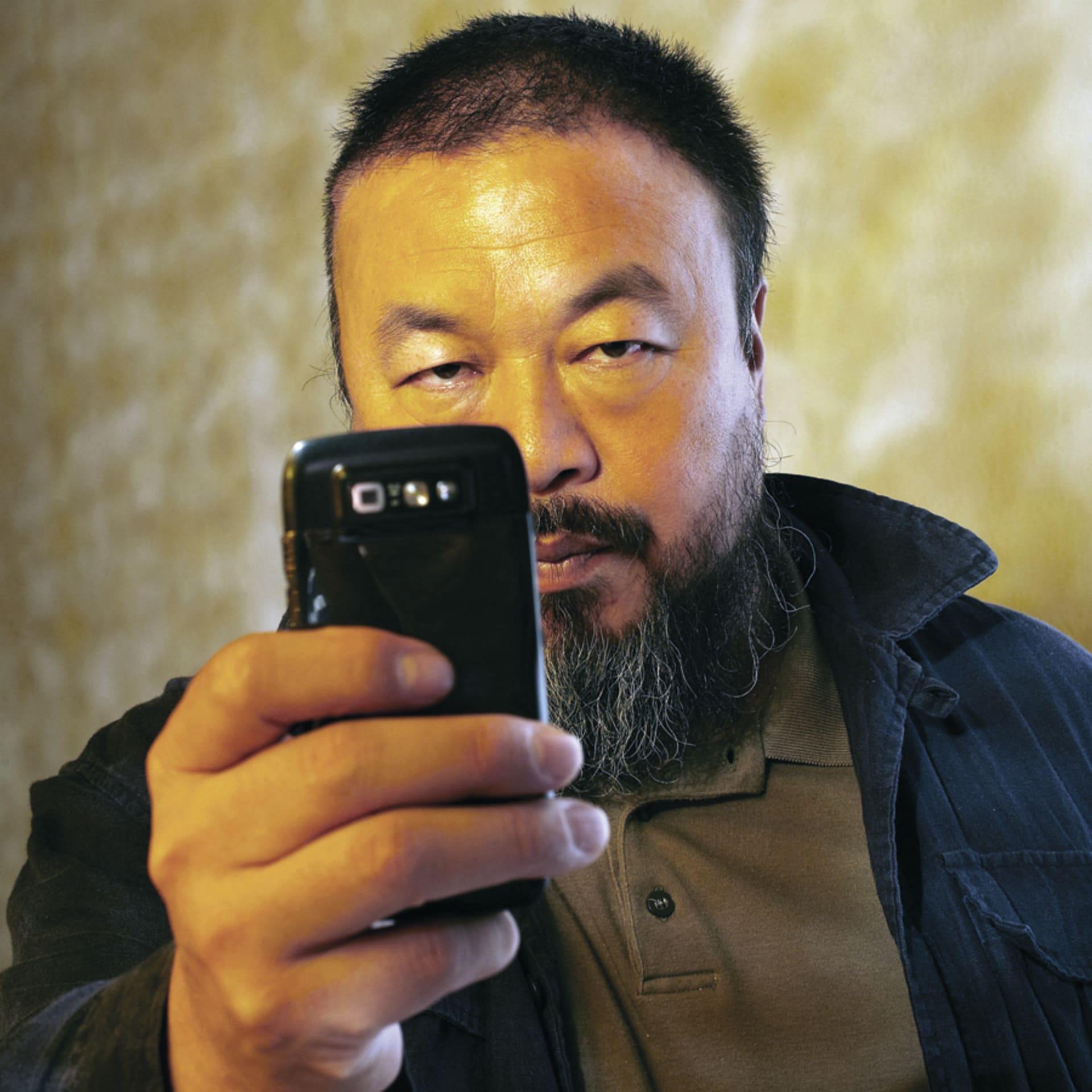

Above: Ai Weiwei, Munich, September 7, 2009, Photo by Frank Bauer/Contour by Getty Images

Last week saw the opening of a new Ai Weiwei exhibition at Berlin’s Martin Gropius Bau, one of the largest Weiwei exhibitions to date. In light of this we are republishing an interview with the Chinese artist from the Summer 2011 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. This issue marked the beginning of the magazine’s change of approach, focusing on the voices of the artist’s themselves. This interview was conducted by art curator and critic Hans Ulrich Obrist, his first contribution to Electronic Beats Magazine.

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957 in Beijing. He grew up in Xinjiang Province and attended the Beijing Film Academy during the late 1970s. In 1979, he helped found China’s premier avant-garde art group “Stars”. He relocated to the United States in the early 1980s and spent a decade in New York City. Since returning to China in 1993, he has emerged as a highly influential cultural figure and a mentor to many of the artists in Beijing’s East Village. Ai’s own creative practice is diverse, spanning multiple disciplines.

Aside from his sculptural output, he is director of the architectural studio FAKE Design, and he built the National Olympic Stadium in Beijing. His contrarian views and criticism of the Chinese government frequently appear in the local and international press. From 2005 to 2009, he has maintained a popular blog that combined writings on social and political themes with an unending stream of photos documenting his daily life.

On April 3, 2011, Chinese authorities detained Ai Weiwei at Beijing International Airport.

Hans Ulrich Obrist interviewed Ai Weiwei at his home studio in Beijing. The transcription first appeared in Hans Ulrich Obrist’s book “The China Interviews”, Office for Discourse Engineering, Hong Kong and Beijing, 2009, edited by Philip Tinari and Angie Baecker.

This is a digital camera.

Yes.

Do you use this camera for your blog?

Yes, the blog is such a wonderful thing. You can talk immediately to people you don’t know. You don’t know their background and they don’t know yours. It’s like walking down the street and finding a lady on a street corner. You speak to her directly, and then maybe you start fighting… or making love.

When did you start the blog?

I was forced to start the blog by a big Internet company. They said, “Oh, you’re well-known, we’ll give you a blog.” I didn’t have a computer and hadn’t done this before, which I told them. They said “No, no—you can learn how to do it. We can send somebody to show you.” In the beginning, I put up older writings and works. Soon after, I started to type, to write, and I was totally seduced. Yesterday, I put up something like twelve blog posts after I came home.

Last night?

Yes, twelve posts. You can put a hundred photos in one blog entry. People often tell me, “You have so many photos from one day!” Photos can be anything… they can be about anything. I think that’s real information, a free exchange. It’s a carefree, responsibility-free communicative solution that accurately reflects my condition.

How many people visit your blog?

Millions.

That’s amazing.

In one day, there are usually around one hundred thousand visitors.

More than any exhibition ever.

Yes, ever. I can have an “opening” every minute of every day if I want to, and this is very important to me. If I make art, I do it on a schedule. People visit the site and come back a half hour later. If I’m lucky, I’ll make a very good installation for someone I don’t know, somewhere I don’t know—maybe in Amsterdam. With the blog, the moment I touch the keyboard, a young girl, an old man or a farmer can read my post and say, “Look at all this different stuff, this guy is crazy.”

So it’s instantaneous?

Yes.

With this camera you take photographs everyday, wherever you are?

Yes, whatever the situation. I guess I’m a bit overwhelmed, because when we grew up, we had no freedom of expression. You could even report your father or mother to the authorities if they said something wrong. This was a very, very extreme atmosphere. Even to this day, people still tell me to be careful and not to be too critical in my blog. But I think that everybody has to do things their own way. So far, it’s been okay. I often discuss political conditions and social problems in my blog. I think I’m the only one in China.

Ai Qing Cultural Park, Jinhua, Jiejang, 2002-2003. Photo courtesy of Ai Weiwei.

Can we look at your blog right now?

Yes, I can show you some of the entries. Life in blogs is real because it’s your own life, and life is about using up time, nothing more. How you use the time is what matters. When I use it, one hundred thousand people are also looking at my blog; they all spend a small amount of time much like I do. A lot of people have said to me, “You can’t stop blogging! You should be careful—if they arrest you, what are we going to do?” Their pleas get pretty sentimental: “We need you! Looking at your blog has become a part of our lives.” It’s very funny.

Clearly, people care…

And they’re willing to wait. If I don’t update my blog, they’ll stay up all night just to be the first one to see the new content and then comment on it. In China, we call being the first to comment shafa, which literally translates as “sofa”. It’s as if the commenter were the first in a room to sit down on the couch. If you’re shafa, it means you’re a real fan and you really care about what I’m talking about. So no matter what time I get home at night, I always blog at least a few words.

Every day?

Yes. At the moment, I don’t know how long it’ll go on for. Maybe it’ll be stopped by the authorities. They visited me once to tell me that my blog entries were too sensitive and asked me to take some of my posts down.

What happened?

We negotiated and they were very polite. I said, “Come on, this is a game. I play my part, you play yours. You can block it if you must because it’s very easy for you to do so. But I can’t self-censor; speaking my mind is the only reason I have the blog.” So they thought about it and called me back and said, “Because of the current political situation, we really respect what you’re doing.” I think China is at a very interesting moment in history. Power and the political center have suddenly disappeared in the universal sense because of the Internet, global politics, and the economy. Various Internet outlets have become key in liberating people from old values and systems… something that’s never been possible until today.

I definitely think technology has created a new world, because our brains—from the very beginning—are based on digesting and absorbing information. That’s how we function. However, neurological conditions change and we don’t even know it. Theories always come later. These really are fantastic times.

Right now.

I think now is the moment. This is the beginning. We don’t know what it’s the moment of, and maybe something much crazier and unexpected will happen… but we see the sunshine coming in. It was cloudy for maybe a hundred years. Our whole condition was very sad, but we still felt a certain warmth. The life in our bodies can still tell that there is excitement to be had, even though death is waiting. We shouldn’t just enjoy the moment, but rather create it ourselves.

Do you produce the moment?

We all do, because we’re actually a part of reality. And if we don’t realize that, we’re totally irresponsible. We are a productive reality.

That’s particularly interesting in relation to blogs. Maybe the blog doesn’t so much represent reality but produce it.

That’s true. It’s like a monster… it grows! I’m sure once somebody looks at my blog, they start looking at the world differently without even knowing it. This is why the Communists censored everything from the beginning on. They are the sole source of propaganda in China, and have been very successful at it for the last fifty years. But because the country is opening up and because the world economy continues to grow with Chinese participation, they won’t survive. They can’t survive and they have to allow a certain amount of freedom. But this can’t be controlled once it is allowed.

“Wild pig in Xinjiang”, 2006. This photograph would eventually become the iconic image of Ai Weiwei’s blog. In: Hans Ulrich Obrist: The China Interviews, Office for Discourse Engineering, 2009.

On the main page of your blog, there is an image of an ox. Perhaps you took the picture in Xinjiang. It’s always the first image you see, kind of like the blog’s logo.

I actually just changed it. It wasn’t an ox, it was a wild pig.

Some people might see it as the blog’s icon or trademark .

Some people used to see it as a blood-colored pig heading west with no direction. It was up for one whole year, so I changed it to one of a cat, because in our architectural studio, my staff spends all day trying to make beautiful models, and then at night, there are eight cats that destroy everything. They’re the only thing better than our government at tearing up the city. The only difference is that our cats do it faster… literally while we’re making plans for the city. It’s really a great metaphor for us because we, as a people, love architecture and design. We try to change the world and build new models that always get torn up and demolished at night. They are beautiful things waiting to be destroyed for their pleasure.

Would you say that cats are architects? Urbanists?

Yes, they are. Cat urbanists.

[Conversation moves to another room, where Ai Weiwei shows Hans Ulrich Obrist some of his new works.]

That’s what I did last night. I was up until 3 am.

So this is a new ceramic series?

Yes. Ceramics are kind of crazy. I hate it… but I do it anyways. I think if you hate something so much, you have to take part in it. You have to use the hate.

As an exercise.

Correct.

And these boxes—are they architectural maquettes?

They’re full of vases. [Opens a box and displays a vase.] These are three- to five-thousand-year-old objects of cultural art. Just dip them into this house paint, and then you can call them “colored vases”.

This is also the name of the series. Is each vase different?

Yes, they’re all different.

Is it all one piece?

No, they’re different pieces. On this vase, you can still see the old painting poking through the surface. The wall over there is part of a new series that I’m doing—I’m creating a perfect wall object that has no meaning, no function. It doesn’t know what to do other than take up space.

And what are these?

Those are part another work, a series of colored Neolithic rocks. They’re anywhere between five to ten thousand years old.

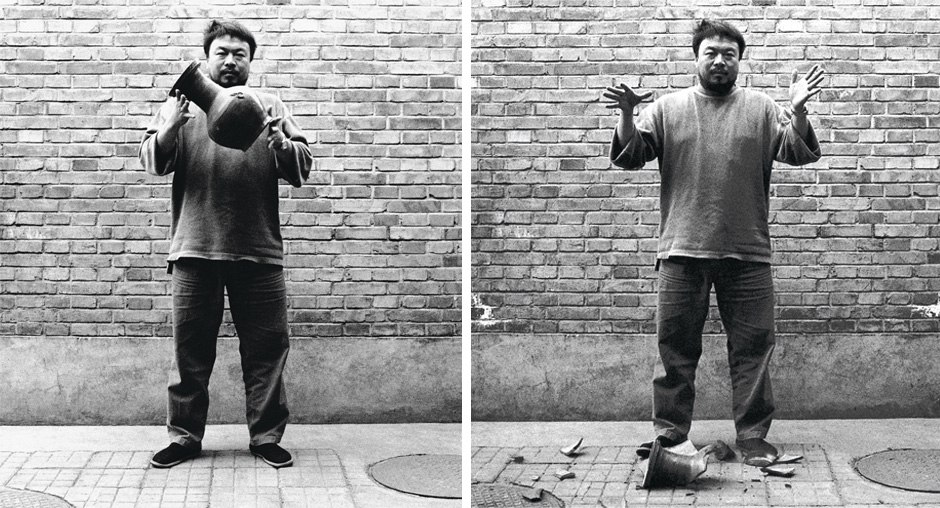

“Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn”, 1995, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne.

I’ve heard a lot about the Museum of Modern Art’s visit to your home. Who came, and can you describe what exactly happened?

On May 20th, the MoMA’s International Council sent sixty or seventy people to China to do a review of contemporary art. That was the day my studio became a landmark on the cultural map. It was a big group with top collectors, top people.

Does everybody who visits Beijing’s art community come to your studio now?

Yes, everybody comes. It’s like a tourist shop—a place you have to go to because it sells ginseng, like it’s really good for your health or longevity or something. Groups come here on their way to the Great Wall. The MoMA group came on the 64th anniversary of when the Communists’ monumental meeting on literature and art at the end of the Long March. There Chairman Mao gave a speech now known as “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Arts” which to this day remains a kind of official bible for Communists. It’s where Mao declares that art exists to serve the people.

They came on the same day?

The very same day… it can’t be a coincidence. Everything’s related, and if we can’t see how at the moment, it only means we’ll understand it better in the future. I said that I should make this anniversary a topic of the discussion because my father had been part of the original forum… he was a top literary figure at the time. But the forum had a destructive effect on art and literature in China, making it devoid of personal and human elements, ignoring the human condition, and eventually turning into something very brutal. Many people were damaged by the ideas that came out of the Yan’an forum. So we decided to do the only thing we could at the MoMA meeting: record the whole thing without the group noticing.

You used secret cameras to record the MoMA contingent?

Yes. We filmed them when they went to Factory 798, then we followed their car from far away when they went to see the artists. Nobody knew. We waited for so long for them to come back. We even have the driver on tape saying, “Fuck! It’s taking them forever just to go to an artist’s studio.” Then they drove to my house. The cameras were hidden in the grass so they couldn’t see them.

Small cameras?

Yes, very small cameras. The whole piece is about showing every possible perspective, recording everyone and making sure we can later identify who everyone is. It’s a very long clip, so I’ll just show you a sample.

[Shows the video on a laptop.]

Here there’s some grass hiding the camera. Soon, the group starts to study the grass. They don’t realize what’s going on.

I think the film gives the impression that it’s a long visit.

Yes, these aren’t old people, but they are all walking very slowly. It’s all really according to their movement.

Are you planning to post the video on your blog? What do you think the reactions will be?

To this? I don’t know. I can’t see the consequences. I just do things without thinking about the before and after.

You just do it.

Yes. I don’t imagine things. I have no imagination, no memory. I act on the moment.

The present?

Yes, the present. Maybe they’ll hate it; maybe they’ll think it is okay; maybe they’ll even like it. It’s perfect because nobody thought to record it.

It’s a protest against forgetting.

Maybe their children will buy it or something.

It’s like a group portrait in a very particular moment in time.

All under some sort of suspicious political and cultural conditions.

When is this piece from? [Points at image of Mao]

Yesterday. This guy died thirty years ago, Chairman Mao. It was just the thirty-year anniversary of his death.

Do you have an archive of your work?

Yes. Here’s an article about the thirty-year anniversary of the death of Mao. I’m probably going to write about what a criminal he was. It’s such a historic situation. A nation that will not truly search for its own past or be critical of it is a shameless nation. We have to work on that. [Pulling up new picture.] Here’s an interesting one: this is my mother’s home in downtown Beijing. Today, most of Beijing has been renovated. My home used to have a real brick facade. One day we came home to find everything had been repainted. I decided to write a blog entry about it.

In protest?

Yes, because this went too far. It’s a very interesting article. [Displays an article from the blog on his computer.] In just one night, the whole of Beijing was repainted. My article is about how we have lost our homeland and instead have a very different world, a different dream. I actually got a call from a magazine today that wanted to print it because they loved it so much. They asked, “Can we take out the political part?” Otherwise it would be impossible for them to print. I said, “Okay, do whatever you want. I don’t care.” [Shows picture.] This was another brick wall. See what they did? They just poured concrete right over it—amazing! This is private property and they don’t even announce the changes. In one day, the whole of Beijing has a new façade, a new skin. Everything is painted.

Very fast.

Yes, very fast indeed. It’s totally crazy… There is so much stupidity and nobody writes about it.

So you write about things that nobody else writes about?

Yes. I mean, what’s wrong with this world? Everybody celebrates crazy, ridiculous things. I wrote a blog post about the repainting and took photos of how they did it. When I went home, I asked my mom, “Why did you allow them to do this?” She said, “They did it to everybody! What can we do? They said it’s good.” I said it’s like putting a gold tooth on a mouse. Why is it necessary ? All the fake walls—it’s crazy. The old town disappeared in one night. I mean, it’s my home. In the end, we decided to take the door off.

You removed it?

I removed one piece and I left one piece.

It would be great to put it in the context of an exhibition.

People can see it and check it out during the exhibition…. every day in Beijing. The title would be the name of my blog. Maybe we can work together on that.

You’d like to collaborate?

Yes.

Fantastic.

We’ll monitor Beijing for you for this show.

Very exciting—thank you very much. Keep us informed. ~

This text first appeared first in Electronic Beats Magazine N° 26 (2, 2011). Read the full issue on issuu.com or in the embed below.

Published April 09, 2014. Words by Hans-Ulrich Obrist.