How Loleatta Holloway Became Disco’s Most Sampled Artist

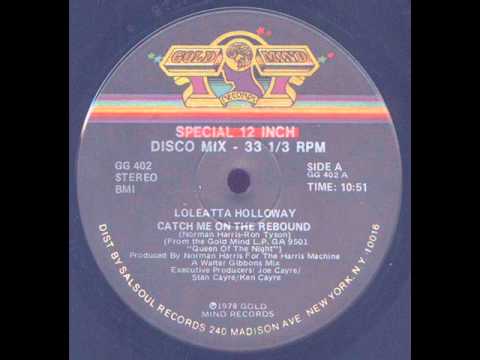

The lead single on Loleatta Holloway’s 1978 album Queen of the Night, “Catch Me on the Rebound,” featured a Norman Harris production, a 12-inch mix by Walter Gibbons and lyrics that displayed emotional strength in the face of adversity. The stellar lineup, combined with Holloway’s swashbuckling entry into disco during 1976–77, gave her reason to believe the track would carry her from local to national notoriety. But instead, it carried the kernel of a prophetic message that defined the artist’s career as she belatedly crossed over into pop not through her own recordings, but in the phantasmic form of a sampled and uncredited vocalist whose lyrics were lip-synched by a model who didn’t speak English. When other producers and remixers started to sample Holloway’s disco tracks rather than invite her into the studio, it became clear that most listeners would only catch Holloway on the rebound—distressed by the breakdown of the old recording certainties, upset that a facsimile was deemed to be better than a performance. To her added dismay, Holloway ended up becoming one of the most sampled artists of the disco era.

The artist made her way into disco through classic roots. Born in Chicago, she sang gospel alongside her mother in a 100-strong choir and joined the gospel group the Caravans before recording two categorically secular R&B albums with producer, manager and future husband Floyd Smith. In 1976, label head Ken Cayre signed her to Salsoul, a vibrant independent label intent on landing a star who could match Donna Summer’s West Coast rise at Casablanca.

Holloway’s first effort, Loleatta, included “Hit and Run,” which DJ remixer Walter Gibbons transformed into an 11-minute exploration of groove music and vamping. Vince Montana went on to invite the vocalist to sing vocals on the Salsoul Orchestra’s “Runaway,” handing her a featured artist credit for her contribution. When Holloway appeared at downtown private party the Gallery to promote songs like “We’re Getting Stronger,” “Dreamin’,” “Is It Just a Man’s Way?” and “Hit and Run,” she found herself strangely lost for words. “I was really surprised that the gay crowd was so into me,” she told me in a 1997 interview. “I didn’t have to build them up. They were already there.”

To Holloway’s surprise if not shock, the multicultural gay crowd that formed such an important bloc within the 1970s dance movement felt a natural affinity with black female vocalists who sang about relationship troubles in defiantly resourceful and emotionally articulate ways. Yet her huge popularity on the New York party scene didn’t translate into national pop stardom, and with the 1978 release of Queen of the Night, she became entangled in Salsoul’s temporary loss of form as Cayre chased the easy buck in the slipstream of Saturday Night Fever’s tearaway run. Holloway blazed back with Loleatta Holloway, a 1979 album that included “The Greatest Performance of My Life,” and her barnstorming contribution to Dan Hartman’s “Vertigo / Relight My Fire.” Released the following year, Love Sensation didn’t let down either as the title track tore up the city’s floors. Holloway recounted later that Hartman made her sing the song 30 times before her voice—supported in the final, successful take by Vicks VapoRub and coffee—reached the hard, deep tonality he wanted for the track. But disco was beating a commercial retreat by the time these records came out, and the Chicago artist reconciled herself to the possibility that a once-in-a-career opportunity had not quite been taken.

For reasons hard to pinpoint, Holloway struggled to adapt to the post-disco era. She had always counted herself among the disco divas that appreciated how the 1970s dance sound had boosted their careers while maintaining that ballads were important as well, because it was on the slower songs that they could properly stretch out vocal range and expressivity. Yet while the likes of Taana Gardner, Grace Jones and Donna Summer rode the transition to the post-disco era by embracing elements of rock, dub and funk within a slower tempo, a new generation of breakthrough divas—including Jocelyn Brown and Gwen Guthrie—confirmed that there was still space for African-American vocalists to record full-throttle dance music. Holloway released only one more record with Salsoul, “Seconds,” a 1982 track mixed by Shep Pettibone. She lost her husband that same year. “In need someone,” she sang on her next track, “Crash Goes Love,” an Arthur Baker production issued by Warlock in 1984.

Lacking the kind of monster hits that someone like Gloria Gaynor could convert into a celebrity appearance career, Holloway slipped out of the musical zeitgeist until Junior Vasquez’s “My Loleatta.” The track laid a recording of a rare Holloway live performance at Better Days over funkified electronic beats, sampled effects and keyboard lines. Vasquez reproduced resident DJ Bruce Forest’s deployment of the original tape, which he laid over house tracks and disco instrumentals such as MFSB’s “Love Is the Message.”

“The speaking part was in sections and lasted about 40 minutes in total,” Forest recalled in 1998. “The crowd went nuts for it and it became my trademark.” Vasquez got hold of the vocal track via Shep Pettibone after the remixer helped himself to the tape against the resident DJ’s instructions, because he had promised Holloway he would never give it out. “He gave this copy to Junior Vasquez, who promptly took my idea, laid the vocal over a house track and made a record called ‘My Loleatta,’” added Forest. “It was a mild success and he made a few more. He also actually put the a cappella on a 12″ and sold it. I was furious, and so was Loleatta.”

If Holloway felt a degree of comfort that she appeared as the credited artist on “So Sweet,” a 1987 release by Chicago house label DJ International, her relationship to the onrush of sampling technology degenerated sharply when Black Box sampled her entire vocal for “Love Sensation” on Italo house track “Ride On Time.” Not only did the production outfit not have permission; it also employed a French model to lip-synch over the Chicagoan’s vocals. Traumatized by the episode, and resentful at the way Black Box were warmly received in the United States by people who knew she had delivered the original vocal, including Soul Train’s Don Cornelius, Holloway found no solace in the record’s international chart success. For sure, sales helped her settle out of court for an undisclosed sum, but given the choice, she would have preferred to have been fully credited as well as paid through a regular contract.

“I thought I was gonna lose my mind,” Holloway told writer and DJ Bill Brewster in 2005. “Seriously. I almost had a nervous breakdown. I couldn’t talk about it without cryin’. I’d spent so long tryin’ to be an entertainer, and I’m not even getting a credit for it? It was like, ‘How dare they?’ Someone’s just taken something from you, right in front of your face.” She added: “For years it destroyed me.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ek-DcfMnYHY

Producers and remixers have gone on to sample Holloway’s vocals more than 300 times, or more than double the number clocked up by Donna Summer, disco’s highest-profile vocalist. Among the most prominent, Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch led the way, inserting a couple of lines from the chorus of “Love Sensation” into “Good Vibrations,” a join-the-dots house-rap track that doubled as a faux duet. This time around Holloway received a credit on the individual tracks where her vocal appeared, although didn’t get name-checked in the artist title and remained skeptical about her clipped video appearance on what turned out to be her second vicarious number-one record. Cevin Fisher drew on the same source in his pumping house track “You Got Me Burning Up.” Ricky Martin teamed up with a virtual Holloway to deliver a fresh version of “Relight My Fire.” In an altogether stranger exchange, Whitney Houston sampled Holloway’s “We’re Getting Stronger” in “Million Dollar Bill,” lip-synching to vocals she apparently couldn’t deliver as effectively as the ex-Salsoul artist. The phenomenon led to some fresh commissions, as was the case when the UK dance outfit Fire Island turned to Holloway to sing a cover of Paul Weller’s “Shout to the Top.”

I got to speak with Holloway in 1997 after Ken Cayre put in a word for me. I knew her music from purchasing the first couple of volumes of Classic Salsoul Mastercuts, and for the longest time had obsessively mixed an a cappella of the artist vamping on “Stand Up” onto everyone instrumental house track I bought. I should have grasped that it was always going to be a tough interview from the sheer length of time it took Cayre to persuade her to talk, but was still taken aback by the speed at which it stalled after I introduced myself by mentioning some of the people I’d contacted while researching my first book. Holloway clammed up as soon as I mentioned Louie Vega, perhaps because Vega had invited India rather than Holloway to deliver the vocals to “Runaway” on the Nuyorican Soul album. “Louie Vega and the whole lot of them, let them do the talkin’!” she said. “They seem to be getting the better of the steak anyway.”

I spent the next half hour failing to persuade Holloway to talk about the sunnier side of her recording career. “Music didn’t do anything for me,” she retorted at one point. “I would probably have did better staying in the gospel and getting me a nine-to-five job. I probably would have been better off than trying to make a career out of this because my career was destroyed, starting with Black Box.” She maintained that “Loleatta Holloway is not even a person,” adding that “you can cry, cry, cry so much and the it’s like, for what reason?” She had suffered more than most. “I know I’m one of the most sampled women there is,” she added. “It’s one thing with the sample if you give someone credit, but when you take the sample and take the credit and you are them, it’s another thing altogether. There’s so much they’ve done to me to just knock me out completely, like I never existed.”

In some ways it was the same old Holloway, speaking her mind, vamping the world to rights, but now the emotion was cold rather than gushing, despondent more than defiant. It was reassuring, then, to read the artist telling Brewster she was over the Black Box period. “You know the other day Marky Mark was on the TV talkin’ about that record and he never even mentioned my name,” she observed. “I’m so used to people like this that it doesn’t even phase me anymore. I remember a time that would’ve hurt me. I’ve come a long way!”

A solidly-built woman who wore her heart on her sleeve, Holloway was always likely to clash with the reckless end of the digital era, uncomfortable with the ease of immaterial recording, the mutability of identity and the ephemerality of relationships. Yet the digital era hasn’t produced its own Loleatta, because vocal chords aren’t whipped into shape the way they used to be, and vocalists along with their producers have come to prefer clean to guttural. Meanwhile the raw feeling and ardent emotion that drove the recording studios and dance floors of 1970s has dissipated into something more provisional and dispersed. Another slice of that era slipped away from us when Holloway died of heart failure in 2011. The 300-plus reworkings of her songs testify to the enduring appeal of her voice, even if they can’t match the original efforts.

Published October 02, 2015.