Inside Superbooth: Are Modular Synthesizers Finally Mainstream?

by Daniel Gottlieb

There was something slightly petulant about the timing of Superbooth 2016. The festival-cum-trade fair for modular synthesizer manufacturers took place last weekend in Berlin—exactly one week before Europe’s largest music summit, Musikmesse, lurches into action in Frankfurt. In light of the latter’s immensity and commercial clout, it’s hard not to think that Superbooth leveraged this one-week intermission as a way to juxtapose the two events. It pits Germany’s cultural capital against the country’s financial capital; Berlin’s Funkhaus, a GDR radiophonic relic, against the Frankfurt convention center’s polished and slick aesthetic; a tradeshow where people arrive by tram or ramshackle boat versus one where attendees arrive by limousine.

Whether the timing comes down to petulance, logistics or simply coincidence, it served as a pointed indication of the rise of a musical niche: modular synthesis. Music writers have referenced the medium’s revival for years now, and hardly a week goes by without the release of some new modular techno mundanity, yet the trend is still regarded as an oddity or a compulsive labor of love in the grander tectonics of the industry. So to organize a modular manufacturer trade fair on such a large scale—three days of concerts, presentations, roundtables and lectures on a large campus—was Superbooth’s biggest and most audacious symbolic gesture. Schneidersladen, Berlin’s internationally renowned hub for modular hardware that also organized the event, has become synonymous with its products’ growing popularity, and now it seems its trade fair will be emblematic of a similar market success.

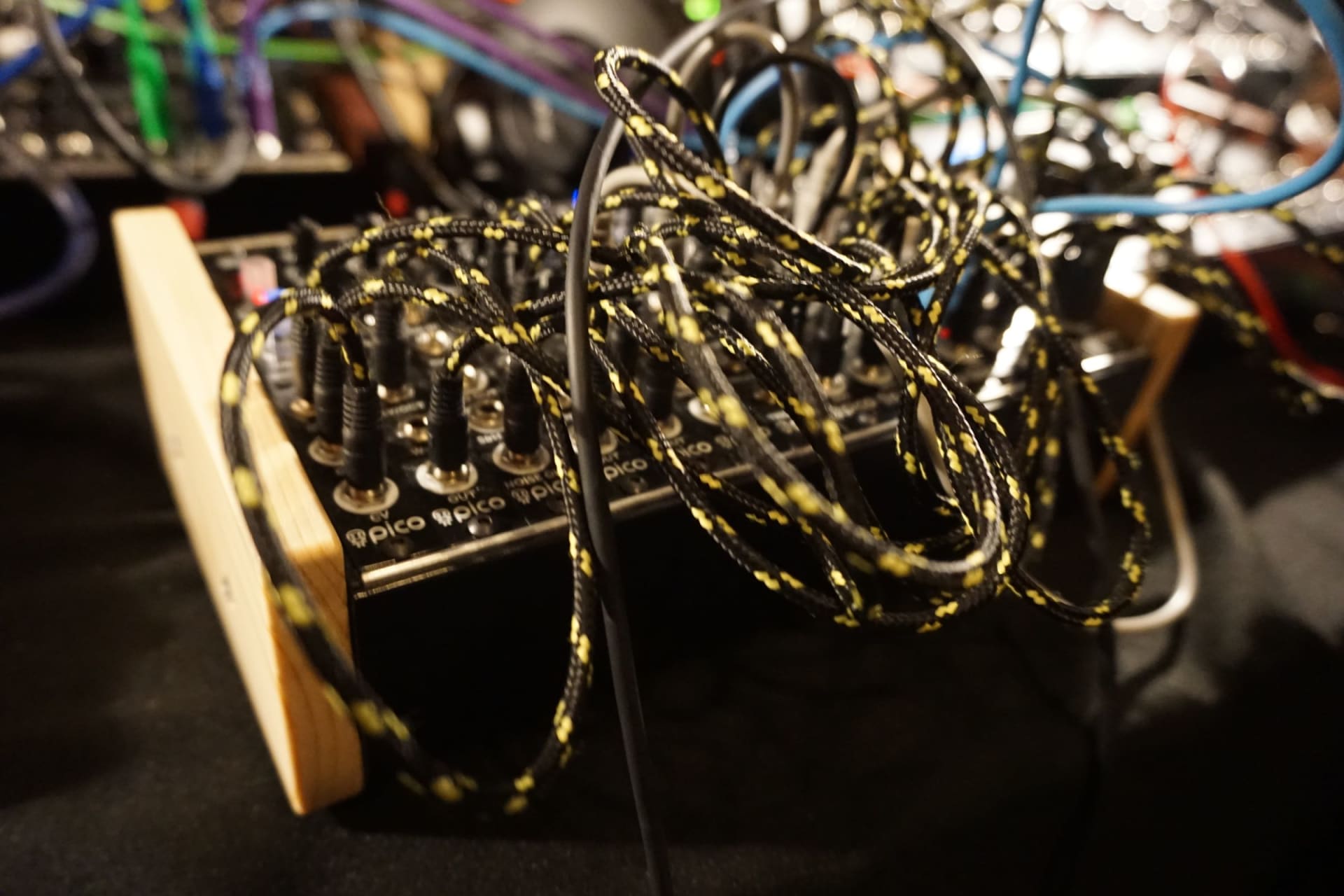

Many at the festival confirmed that it was the largest showcase of modular manufacturers ever. Well over 70 manufacturers showcased their inventions in Funkhaus’s main hall every day, creating a sound-carpet of basic and unrelenting drum patterns, atonal sequencers, filter sweeps and oscillator feedback that sounded like an unsynced version of your stock-standard “annoying” modular jam raised to the power of 50. Roger Linn presented the Linnstrument, a MIDI controller that he believes returns live virtuosity to electronic performance with its new interface capabilities. Dave Smith, Korg and Roland also had arrays of gadgets on display, and Roland’s Minilogue garnered a lot of attention for its functionality and affordable price. Koma-Elektronik presented a powerful quadraphonic module in the Saal 2 performance room. 4ms displayed an interesting loop module that toys with computer algorithms to create dense and multi-dimensional rhythms. JoMoX head Jürgen Michaelis revealed the event’s most bombastically designed synth: a dodecahedron-shaped, revolving orb that produced wonderfully detailed and rich glacial pads and timbral shifts.

All these machines testify to the general point that modulars have the basic capacity to produce bizarre records of immense quality. Judging from many of the conversation-presentations at Superbooth, the drive for weirdness, sound color, variety, flexibility or precision never ceases to increase and is matched only by the insatiable demand of many to get their hands on these pieces of gear. So it was interesting to hear how the festival curated its performance program, given that the bookings would further elucidate the art of modern modular music practice.

But regardless of the impulse behind their selection, most of the shows ultimately collapsed into some kind of 30-minute blend of gear perving and envy. This felt most obvious during the evening and nighttime programs, where it was hard to avoid the sense that any critical impressions were bolted to a Baroque, religious awe of seeing well over 10,000 euros worth of circuitry at work. At times it seemed that the music could too easily hide behind the modulars producing it, which allowed any musical idea to remain sheltered from critical exposure.

Of course, there were some interesting sounds within the performances, regardless of whether they comprised tech-house, techno, drone or post-Berlin School trance. All the high-quality gear inevitably made for impressive-sounding acid lines, kicks and pads. However, in the majority of cases, I was hard-pressed to feel like the lauded explosion in modular systems or the expansion in their possibilities, connectivity and applicability really translated into a true aesthetic force.

For me, the festival’s three supreme performances came from musicians with minimal or classic setups. Frank Bretschneider’s raw set of overheated pulse blasts and tonal stretches really felt like he was pushing electricity to its limits all with only a Machinedrum and a looper. Robert Lowe played an extremely patient set of organic CV-controlled drum patterns, voice and warm pads with a small modular setup. It felt like an exercise in tool-making that investigated the applications of what his modular could do given its inherent limits, rather than a showcase of all the gear he’s hoarded over the years. Even Max Loderbauer’s Buchla 200e performance—the musical highlight of the Superbooth 2016—showcased a subtle understanding and respect for what modular systems can do and fused the machines’ tendency towards certain sonic palettes with the performer’s own musical expression.

The bulk of less-than-awesome performances brought a nagging feeling I couldn’t shake throughout the festival into sharp relief. The size of the event, the grandeur of the muscians’ systems and the quantity and variety of products on display engendered in me a feeling of commodity lack, which in turn inspired more of this hollow awe at my surroundings. The justified celebration of modular music’s explosion started to seem like an explosion of supply-side products whose demand rarely resulted in any groundbreaking performances.

Modular music’s introduction into the homes of hobby musicians is definitely a cause for celebration. But it also opens the traps of false difference and rampant, compulsive accumulation that exist for all products on the free market. For the moment, vendors and purchasers seem to be willing participants in their race-to-the-bottom to own the best 303 or 808 emulators, the most insane kick drum or the most bent sequencer. But that insanity, sound quality and weirdness rarely found its way into the music, both live and recorded, in a manner much different to what we have recognized for 40 years. Trade fairs have become a necessary feature of any important business—a development that might have been the most amazing and scary thing about Superbooth ’16.

Cover photo courtesy of Create Digital Music

Published April 06, 2016.