Jeff Mills and Ólafur Elíasson ask: “What If We Had Two Suns?”

In part one of our in-depth conversation between techno progenitor Jeff Mills and renowned installation artist Ólafur Elíasson, the duo fervently discussed the digital future of education, viewing reality through the lens of culture and the possibility of sentient art works. Here in part two, Mills and Elíasson explore how the world would be different if we orbited two suns.

Jeff Mills: I once met an astronaut, Mamoru Mohri. He’s the first to have gone into space for Japan, in 1992, and he went on a second mission in 2000. We had many conversations about the psychological effects of his trip. I asked him if he was the same person when he came back, and he said no. He said that there were things he had experienced, things that he had seen, feelings that he had of being in cold space that he could never explain to his wife and children or put into words. What he spoke a lot about, actually, was the sun. He said the sun will definitely be the thing that ends our civilization—that it’s the most dangerous thing that we could ever imagine. Of course, it’s the thing that makes everything grow, too, but we’re also living at its mercy. So I was wondering about your relationship with light, and how you use it. When I walked through your studio, you had lots of works that were positioned to use the reflection of light through windows and things like that. What are your thoughts about the rays the sun creates?

Ólafur Elíasson: I am a sun nerd, and I sometimes imagine that I’m on the sun, or I’m in the sun, or that I’m trying to see the earth from the perspective of the sun. I’m interested in how to make the energy that comes from the sun more tangible, not just literally but also emotionally. What does light feel like? We know to a great extent what happens when light bounces off a surface and what happens with color, how much of the energy is transferred into heat waves and what is visible. This is interesting to artistic ideas, but the psychology of it is also fascinating, because you almost need to take a perspective from outside of the earth to understand what we look like. There are a number of famous quotes and pictures of the earth rising above the horizon of the moon, when Armstrong was the first man on the moon in ‘69. What does it take for us to see ourselves in a greater perspective? Only then can we actually ask things about interdependence. And the whole issue with the climate is so hard to get your head around—the fact that the globe as an object is struggling.

JM: OK, I have another fun question here. If we existed in a binary rather than singular sun system—if we had two suns in the sky, as some planets like Alpha Centauri do—what type of effect do you think that would have had on humans?

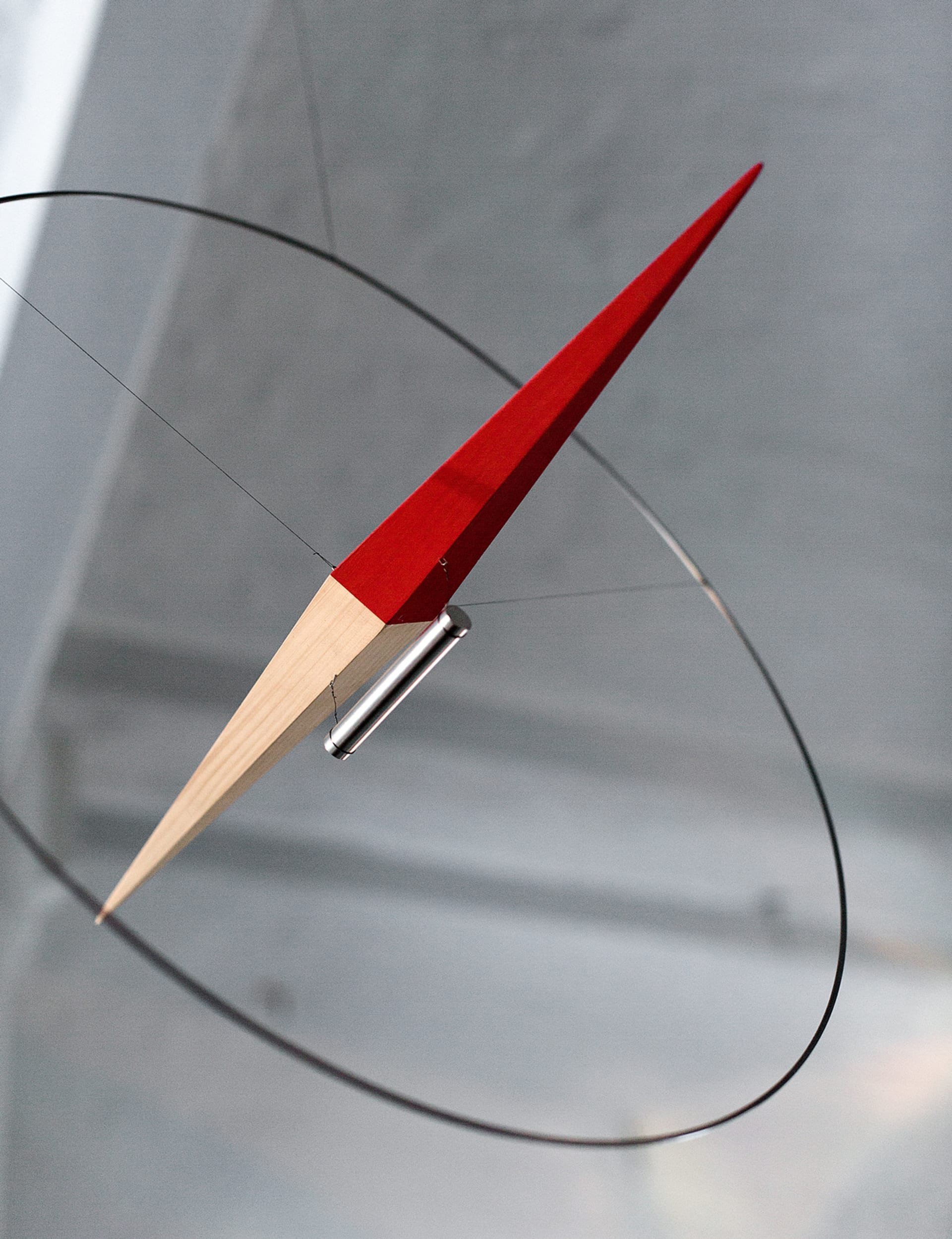

OE: I worked with the idea of a double sunset, and there are a few lovely images of two suns in science fiction movies. The idea is, of course, amazing. It also reminds you of another important aspect: the shadow. In our society, the shadow is an underestimated but incredibly important indicator of spatial depth, positioning, and time. Are you side-lit, are you top-lit? If you’re at the equator, you’re more likely to be top-lit—there is little or no shadow. When you are at the Northern or Southern hemisphere, there are long shadows. I think this has influenced our culture, our architecture and our heat management. Our identity is connected to the quality of the light and the sun, so adding an extra sun to that equation is a great idea.

JM: We live with the idea of a single god, a single power. If there were two forces like that, how would that shape religion? Perhaps we would not be the people that we are. Maybe we would not be so conflicted.

OE: Clearly, these two suns would have existed since the beginning of time, and that would’ve meant our sense of central perspective would be less centralized. You would have two shadows: one would be long, and the other would be quite short. I was with a goalkeeper for a soccer team the other day who said he loved evening training. There were two lamps behind the goal, and by looking at shadows, he could see the distance between himself and the goal. There would also be navigational consequences if we had two suns. It’s a fantastic thought.

To be a little more intelligent about your great question, clearly the revolution of the earth—one revolution every 24 hours—is based on one sun. I’m very interested in how we on earth know that we are turning. One way of knowing is to look at the sun. As we all know, the sun doesn’t actually move. It looks like it does, but it’s us, you and I, Jeff, traveling 300 kilometers a second or something insane like that through space. Having two suns might bring the earth to orbit in a kind of infinity sign around two suns, which would be beautiful.

JM: Right. What effect would that have on nature or animals? How would moons and satellites fit into that scenario? How would we age? It’s kind of interesting to see how we’ve shaped our lives around a singular sun. I just wonder if we would look at two suns the same way that we look at one. How would we look at each other? Would we walk through life imagining that we are so self-conscious, for instance? Would we attach ourselves to other people more easily because of the way that we’ve been taught by the sun and its relation to its twin? Would we have a type of personality that was more like a Gemini, like myself? On Monday I’m one way, on Tuesday I’m somebody else. It drives my wife crazy, but that’s the way it is. Would we have split personalities?

There are places in the universe that have these binary suns, and very far in the future, humans could find themselves in situations where they have to psychologically recalibrate themselves to accept the effects of all that happening. In 2020, we’re supposed to send people to Mars on a one-way trip. I wonder if they’ll make it—if they’ll be able to cope with how different it is.

This is an online-only extension of an article that appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from our print issues.

Published October 23, 2015.