Krautrock Icon Michael Rother Talks to Roman Flügel

“Today it’s always said that in a certain sense, Neu! is proto-techno. But I’ve never felt that,” Roman Flügel recently told krautrock legend Michael Rother over coffee in a Hamburg cafe. And still, employing trance-inducing elements of repetition as building blocks for long, spiraling musical exploration seems to be a tradition in which German musicians have helped innovate across time and genre, including Flügel himself. On his last album, Happiness is Happening, he offered up an homage to German synth music traditions, kosmische in particular, which is why it’s surprising that the dance music icon and co-founder of the Onagaku imprint insists that the conceptual bridges between krautrock and first-wave German techno were subconsciously constructed, at best. But as he points out, his approach to making music—unlike Michael Rother’s historical reinvention of rock and pop—was never about creating “new” sounds but rather rearranging prefabricated puzzle pieces into a unique but recognizable image of dance music.

For Michael Rother, the rise of dance music in the ’90s was something that barely registered on his musical radar. At the time, the co-founder of Neu! and former member of Kraftwerk and Harmonia was embroiled in legal battles surrounding the rights of his solo material and genre-defining Neu! classics. The eventual resolution, massively influential Neu! re-releases in the year 2000 via Herbert Grönemeyer’s Grönland Records label, helped usher in an era of krautrock’s mass rediscovery and canonization. Here, Rother and Flügel discuss narratives connecting hypnotic German genres and whether patience, beyond being a mere virtue, is also a common musical strategy.

Roman Flügel: Michael, I always hear a great sense of concentration and focus in your music, especially in your solo work. Do you have a particular approach to focusing or calming yourself, musically speaking?

Michael Rother: You need to really go inside yourself and hope that something happens through this internal analysis. Usually, it’s the finer aspects of emotional processes that can be found and then expressed through music. On the other hand, I love excitement. So there’s a good reason why I’ve lived in the small German town of Forst an der Weser since about 1837 [laughs]. I always end up coming to Hamburg in winter because it’s easier to endure cold weather in a city. But the rural tranquility, open space and fresh air in Forst are incredibly beautiful. When I look out the window I can see the Weser river, which runs right past my house. Behind it are miles of rolling meadows. It’s breathtaking. I passed through there by chance in 1971 with Kraftwerk, when I was playing in the band. I can still clearly remember how I looked out from our bus and being totally overwhelmed by this landscape. Two years later I found myself there once again while looking for musicians for the Neu! tour. Cluster—that is, Roedelius and Dieter Moebius—had been living in Forst for two years at the time. And then I decided to stay. That environment helps me to concentrate and to be calm. You live in Frankfurt, right?

RF: Yes, I live in a rather notorious district near the main railway station. A lot has changed in the last five years. Gentrification is happening with vengeance. Joy and sorrow still live side by side in Frankfurt. There are still a lot of junkies, a lot of people who have no money just trying to survive day-to-day near the train station. On the other hand, expensive apartment buildings have sprouted up for all the Deutsche Bank and European Central Bank types, and that obviously alters the structure of the district. But I grew up in Darmstadt, on the edge of the Odenwald forest. My parents’ house was completely idyllic, with lots of birds and a lot of nature. I moved away when I started my studies. City life has the advantage of being able to travel easily. The airport is just around the corner, yet the city center in Frankfurt has luckily been spared all the aircraft noise.

MR: There’s neither a highway in my immediate vicinity, nor a good train connection. But as you just mentioned birds: hearing birdsong is an experience that I enjoy anew each spring when I leave Hamburg and go back to Forst. When you’re surrounded by birdsong, your hearing chages immediately. It gains more depth.

RF: We have pigeons cooing, but that’s not quite the same thing.

MR: But do you know what I mean by depth regarding birdsong? You can hear precisely the distances of certain sounds. It’s like a healing shower of precision for the ears. By the way, how old are you?

RF: 44.

MR: So a generation younger than me.

RF: Yes. I first became aware of your music when Grönland reissued the Neu! albums. I already knew the later Kraftwerk, of course, but the rereleases were when I discovered much of what was happening around it, as well as the early Kraftwerk, of which you were a member. And the music captivated me immediately. This goes for Neu!, Harmonia and, of course, your solo records. I bought quite a lot of them—essentially after I bought a bunch of Brian Eno records and figured out his connection to your world. What I find so fantastic about listening to the music you made with Klaus Dinger [drummer and founding member of Neu!] as well as with Roedelius and Dieter Moebius in Harmonia is the completely different attitude towards what rock or pop is supposed to be. You radically broke with a lot of traditions and from that, entirely new approaches and paths suddenly appeared.

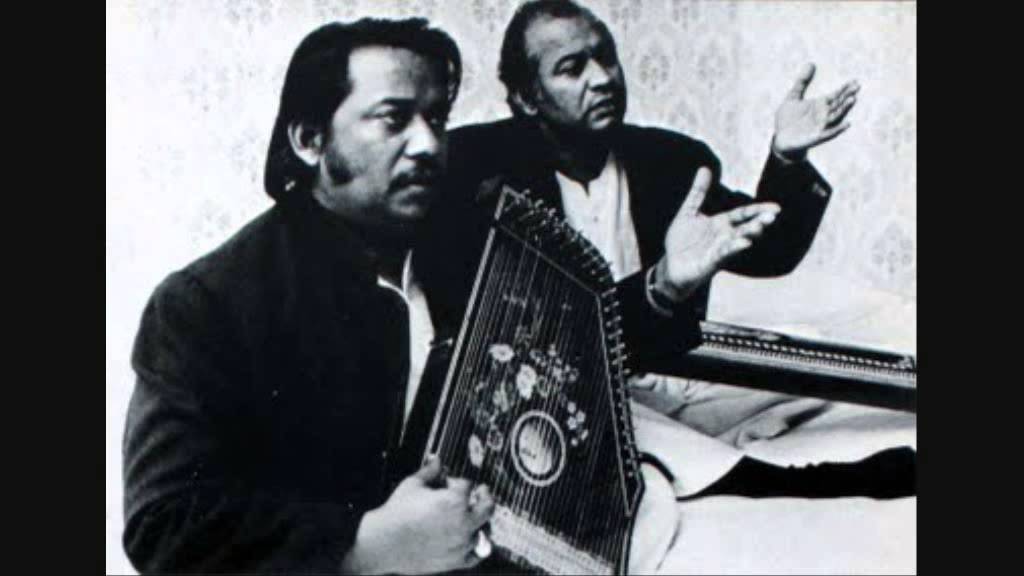

MR: It’s nice to hear because that is exactly what we wanted to do back then. For me it was always about forgoing all those classic structures, and to somehow discover a new musical continent. That was the aim. Klaus [Dinger] always had an ear for the essence and effect of pop. You can also hear it in his later work with La Düsseldorf. That helped me, because I was never looking out for that. I’ve always been more surprised if something especially pop-like comes out of what I’ve done. That was also the case with my solo albums, like Flammende Herzen or Sterntaler. The question for me was always: What can I draw from if I try to forget about Jimi Hendrix and American and British pop music? That’s why I turned to German folk music and children’s songs and also the classical compositions that I grew up with. And, of course, things that I had heard in Pakistan, where I lived for three years when I was nine. My father worked for Lufthansa and was stationed there. To this day, Pakistani music touches me in a very special way, especially the brothers Nazakat and Salamat Ali Khan. Their music flows on a kind of wave, with these two singers who always take up the thread and build the music in incredible ways.

RF: I’ve been going to India at least once a year over the past three years and the music touches me in a similar way. I eventually discovered Vedic chanting, the music that Brahmins, the elite priest caste in Hindu culture, created over decades with only their voices. It has meters that are completely foreign to us but which totally fascinate me. For me it’s primarily about the sound and the rhythms. In a sense it also reminds me of Harmonia, as you hear rhythms that overlap and time signatures that are unfamiliar to European ears. Were you consciously referencing such musical traditions, or was it the random results that came from your attempt to synchronize two drum machines?

MR: We never theorized much. I think the odd time signatures came from Roedelius. He played those kinds of melodies on the piano for hours, and that fascinated me. That was the reaosn why I absolutely had to make music with Harmonia. Throw in the surprising interjections from Moebius, and you had a kind of music that could happen on the spot. Like on “Watussi,” for example. That’s Roedelius, who sometimes got carried away playing with delays and getting into an almost trance-like state with these loops running the whole way through. We never ran two drum machines simultaneously. What sounds so messed up was the result of our edit and approach. For example, we ran a drum machine through a wah-wah pedal and sent them through a tremolo, which, of course, weren’t synchronized. We couldn’t do it any better back then, but it has a very special energy.

RF: The studio setup that you had with Harmonia in Forst is known from photos: two nearly identical blocks of keyboards and effects units, with two guitars in front of them.

MR: Right, the heavy Gibson and the light Fender.

RF: The leopard print Fender always fascinated me.

MR: I bought that off Florian Schneider from Kraftwerk. I still have it. Nice and light, a Fender Mustang with a tremolo bar. I eventually removed the leopard skin because it became unappealing to me at some point. Florian had also decorated the guitar with colorful stones.

RF: What I always wanted to ask you is: What role does ego play in music for you? After Neu! and Harmonia did you choose to go solo in order to fulfill your own musical vision?

MR: For me, it’s a pretty straightforward development from Neu! to Harmonia to my first solo record. I couldn’t have omitted any of it. I never would have ended up with Flammende Herzen or Neu! ’75 without Harmonia. But the fact is that Harmonia failed at the time. It was simply a commercial flop. In 1976 we reached the point where we really just stared at each other and said, “It just can’t go on like this.” I suddenly found myself alone, and to get back to your first question, I had no other choice than to go solo. Flammende Herzen emerged out of that situation. Not because I wanted to finally gratify my ego, but simply because there was no one with whom I could collaborate. For me, it was an experiment: What comes out if I make music alone in the studio? The key to that happening was Conny Plank. As a producer, Conny had the incredible ability to understand and empathize with the ambitions of the musicians who recorded with him. He once said that he sees himself as a midwife who helps musicians to deliver their babies. Which is to say he works without pressuring you. He also sometimes subtly placed limits, without it being clearly noticeable, by saying at the right point: “It’s good like that.” There’s a lot happening spontaneously in the studio on Flammende Herzen. Conny and I never had any disagreements. Whatever he did, I always liked it.

RF: How was your work with Conny Plank financed at that time? I’ve had the luck that I’ve been able to build my own home studio gradually, and the means of production have become cheaper. For you, considerably more money and effort was needed in order to get anything onto tape.

MR: Indeed, it was stressful. Commercial studios were expensive. We always worked at night, because it was cheaper. For the first Neu! album, Klaus and I had four nights for the recordings and then a week of mixing in another studio, for which the owner of the studio got the publishing rights. That’s how things worked at the time. We somehow scraped the money together. That was also what was so special about Conny Plank: He shared the risk with us. Of course, it meant that he was involved in the licenses. But as an overall matter, it was hell. We suddenly could record on 16 tracks for the second Neu! album, where the first was recorded a year earlier on eight. We failed spectacularly with these new opportunities: “Oh, I’ll play another guitar and another reverse piano, and I can still throw a violin there.” And then the week was nearly finished, and what did we have to show for it? One side of an album. Then the B-side emerged in a crazy night, where Klaus kicked against the turntable so that the needle jumped. [Side two of Neu! 2 consists of previous singles, “Neuschnee” and “Super,” played in various speeds from both tape and a record player.]

RF: I have to admit, I was incredibly irritated by that the first time I heard it.

MR: I hated Klaus for it, but it was the result of sheer desperation. He would probably never have admitted it, but it’s the truth. We had these two pieces, “Super” and “Neuschnee,” and it was clear that they would be on the B-side, but they had a total of maybe six and a half minutes, so it wasn’t enough. And then Klaus put our first single on the record player and let loose. Later, the B-side of Neu! 2 was considered the first remix experiment.

RF: Indeed, today it’s always said that in a certain sense, Neu! is proto-techno. But I’ve never felt that. The fact that something is repeating has absolutely nothing to do with techno. Your music grabbed me on a harmonic level that pop music or the music that otherwise surrounded me never did. It was a different sound. I never associated it with techno. I made my first record in 1990 and I had no idea of your music back then. I didn’t know that something like that had ever existed in Germany! During the ’90s, house and techno led to the development of a new scene, which I was part of. People in Germany once again found their own language with electronic music, but for me at the time it had no connection to what you had established in the past. I still see it that way today because so many people who produced records in the ’90s had absolutely no idea bout music from the ’70s. Techno and house are and have always been club music and a unique youth culture, which has little to do with what was done in the ’70s. What happens harmonically on your records together sounds incomparable to me. One could draw the connection between your music and techno, but in the end it’s constructing something else.

MR: I noticed the development of techno only from a great, great distance. I wasn’t hanging out in Berlin or in the other cities where a lot of it happened. I can remember that I sometimes heard something on the radio and thought: “Ah yes, so that’s happening now.” But it didn’t really leave its mark. I maybe briefly considered it in order to see if it could serve as an inspiration. Repetition, of course, always does, like the magic of repetition I found in Pakistan, not just the strange sounds and melodies.

RF: For decades, repetition was something that people in Germany pretty much never got to learn. It was always more about pushing variations to extreme, to have as many combinations and changes as possible before something repeated. On the other hand, techno was an almost archaic approach to music, which felt extremely liberating to me when I started to work with machines. There is also a very important difference between the way your music was created back then and how mine has always been created. Namely, I was influenced by pre-existing record collections, by sampling techniques and the availability of music. My music consists more of puzzle pieces, of various connections that I make between different things that I’ve heard in my life. I never had the intention to break with everything that came before. And that’s a very big difference in approach.

For me, house and techno in the late ’80s and early ’90s was the most radical thing you could connect with at the time. I left the bands in which I had played as a drummer until then, and in the late ’80s, started to produce on the cheapest bits of equipment. My music has always been created as a form of sampling. I know you’ve said that you wanted to leave everything that was there before behind you. An important part of what you said was to withdraw as much as possible and not listen to much music in order to have your own sound. For me, it was always very important to hear a lot of music and to somehow process what fascinated me. I suppose it also had to do with different times. I’d be curious to know: How were the late ’80s and early ’90s for you as an artist? The positive mythologizing of the ’70s hadn’t really taken place yet.

MR: The ’70s were pretty much “out” during the ’80s.

RF: Exactly. How did that feel?

MR: It was difficult. But I had the good fortune to regain the rights to my first three solo albums after five years. The manager at Polydor then offered me a rather lucrative contract. But you could see quite early on that Deutsche Grammophon, which Polydor belonged to, was reorienting. They released a compilation called Alles für Zuhause (Die Neue Deutsche Welle) and stuck on one of my tracks. They probably thought they could somehow still shove me into this market where I didn’t belong. That’s when the trouble began. Not financially, but artistically. At the time, the public moved away from what I was doing. By the end of the ’80s, there was no interest at all. I prematurely terminated the contract with Polydor. I then continued to work for four years. It was pretty exhausting, because I realized that I could no longer relate to the reality out there. Then in 1993 it became clear that I could no longer wait for things to fall back into place. Consequently, I founded my own label and released everything myself.

RF: That was also exactly the time when self-releasing became possible for me. Those structures emerged at the time. From then on, it was another way of working.

MR: Well, it remained difficult for me. Also because of the endless discussions with Klaus about Neu! reissues. It wasn’t all fun and games.

RF: Of course. Then let me ask you some more about Harmonia. Harmonia and Kraftwerk both recorded two very important albums around the same time…

MR: I believe Kraftwerk’s Autobahn came out one year after Musik von Harmonia.

RF: Yes, which is interesting, because I think that on the title track “Autobahn,” something happens musically that for me sounds exactly like a part of the Harmonia album.

MR: Really? I’ve never heard that. Great, I’ll sue them! [laughs] What do you hear there? I’m very interested to know.

RF: It comes in that middle section, where there’s a melody that, to my ears…Well, I’d have to have the tracks side by side.

MR: I would not insinuate that Kraftwerk had taken anything from Harmonia. But I can remember quite clearly how I proudly came to Düsseldorf with the first Harmonia album. I met up with Ralf and Florian in a billiard bar and then played the album to them in the car. I can even remember that they were especially impressed by one of the pieces, called “Veteranen.” And you know that I’ve jammed with Ralf Hütter. Back then it became apparent that we were on the same melodic path. It was a revelation for me, because at the time, to my mind, there was no one in sight who wanted to do anything similar to what I was doing. With other musicians, there was either still blues in what they were doing, or it was complicated and overly intellectual. With Ralf, I could immediately relate. That compatibility between us is perhaps a better explanation of where the similarity in the pieces come from.

This conversation was translated by Alexander Paulick-Thiel and originally appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from the magazine.

Published September 02, 2015.