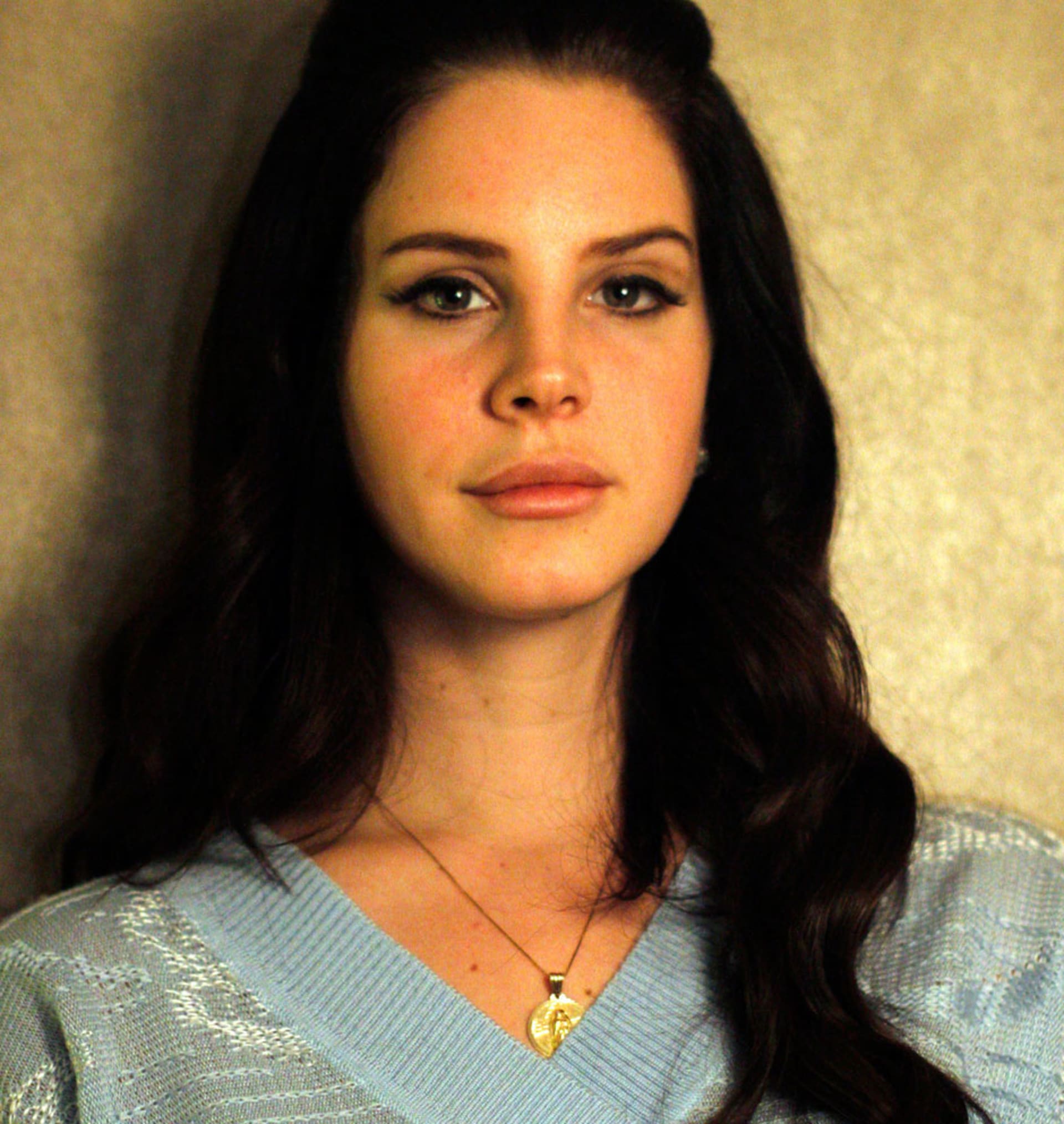

Paradise Lost: An interview with Lana Del Rey

In this special preview of our new Summer 2013 print magazine, we present the cover story—an extensive interview with the divisive pop phenomenon—in full. Photo by Robert Carrithers.

Lana Del Rey’s “Video Games” went viral in 2011, bringing international scrutiny to her former life as Lizzy Grant. Whether it was the languid coquettishness, her sultry, wide-ranging contralto, or undefined charisma, Del Rey became the face that launched a thousand think pieces; a lightning rod for feminist critique and the inquest of authenticity. The cover portrait of 2012’s Born To Die echoed Grant Wood’s iconic painting American Gothic, itself an appropriate term for her music. The album’s familiar, somewhat old-fashioned approach to songwriting and the sepia-soaked imagery evoked a sense of nostalgia. But combined with the explicitly modern lyrics and production flourishes—hallmarks of an innocent, bygone era framed in knowing darkness—it created a unique tension, especially apparent in her EP Paradise. That release’s single, “Ride”, and the accompanying video, seemed to encapsulate every argument surrounding Del Rey, portraying her as submissive, promiscuous, a prostitute, and glamorizing guns and senseless rebellion. But peel back the layers and a different, if still post-feminist, story emerges. She may not claim it, but Del Rey understands the power her image has. And she uses it, regardless of public opinion, to further her music—surely the most overlooked element in the talk surrounding her person.

Lana Del Rey: I haven’t talked to an American journalist in, like, forever.

Really? I don’t count, though, because I’m an expatriate.

Me too. I think America is amazing for its landscape and its history. California is beautiful, New York is beautiful, but when you’re a gypsy at heart, it probably suits you to be traveling.

You think you’re a gypsy?

I don’t feel that way as much as I used to. I actually don’t feel that way that much anymore, but when I was younger I used to really want to have an unpredictable life where I could feel free and travel anywhere I wanted to, whenever I wanted to. I actually really like California now, although I’ve never lived there before. I like the idea of living in one place now.

But you grew up in one place?

Yeah, I grew up in Lake Placid, New York until I was fifteen, and then I went to boarding school for three years in Connecticut. Then I moved to the Bronx when I was almost eighteen.

First, let’s talk about your style, because you definitely have it. Was there an iconic figure that influenced that?

Like musically?

No . . .

More looks-wise? Well, vibe-wise. The funny thing is that my style is something that no one ever asked me about until a couple of years ago. For years it was all music driven. I really loved Nina Simone; Kurt Cobain was my driving influence; I listen to everything Bob Dylan did . . . But in terms of actual style icons, female icons? No. I was impressed with what someone like Karl Lagerfeld built and did and the house that he made, but there was never really a female figure I wanted to emulate.

Karl Lagerfeld? That’s really interesting because I never would have associated the look you have with someone like him.

Yeah, I know. But a lot of the reason my look is the way it is is because it’s really easy to put on a sundress every night if I have to perform—or just wear jeans every day and a flannel or something. Stylistically, I love make-up. I love doing my own make-up and stuff, but clothes-wise, I actually didn’t ever really care. Initially the fashion world was more interested in me than the music world, which was strange when I first started singing.

Your music and your image often seem inseparable.

Yeah. It is now, but it shouldn’t be. I don’t actually care. But because of the way I look, it looks like I really do care.

So that means you do separate the music from . . .

Yeah, because I don’t believe . . . well, I don’t know how to put it. I don’t think it’s appropriate to try and look extremely beautiful. I don’t think it’s a good message or focus. I actually have been writing and singing on the Lower East Side since I was seventeen, but a lot of a person’s history doesn’t really translate.

So how important is it to have total control over your image, especially today?

It’s important—really important. It’s hard, though. It’s gotten totally taken away from me. I don’t have that much control because things go viral really quickly. I went from having no real fan base or interest to having a lot of really skewed interest and criticism. But for the majority of eight years before that in New York, I sang to the same people in the same bars and had a pretty comfortable experience doing that. That’s not really possible for me anymore, because bloggers are really influential and people are really influenced by reviews and five star critics. And those people are really influenced by images, and what they see quickly. Also, a lot of what’s been written about me is not true: of my family history or my choices or my interests. Actually, I’ve never read anything written about me that was true. It’s been completely crazy.

When did you realize that it had gotten out of control?

The first day that anyone ever wrote about me, as soon as I put “Video Games” up. Everything they wrote was fucking crazy. Like about my dad, about me, like having millions of dollars, and all this shit. I was like, “Really? I thought I was supporting everyone!” [laughing] Everything was not true. As soon as the first person wrote about me, the articles became just blatant, all-out lies. I consider it slander. If I cared more, I’d kill them.

Obviously you will know that in preparation for this interview I read a lot of that stuff.

Yeah, but none of it’s true.

Because there does actually seem to be a disconnect between your public image . . .

And who I am?

And the private life you talk about.

There is a disconnect, yeah. I spent the last ten years in community service and writing folk songs. I don’t give a fuck about what I look like. Saying I came from billions of dollars is crazy. We never had any money. I feel, as a person who grew up reading about and being inspired by other figures with integrity, to kind of be turned into the antithesis of that is not what I planned. It’s the way it’s going right now, but I deal with it as it comes.

Let’s go back to what you said about doing community work. Social work involves working with people that society has forgotten or left behind, or who simply can’t function in normal society. It usually involves reintegration . . .

I’m not a trained social worker. I’ve been sober for ten years, so it was drug and alcohol rehabilitation. It was more traditional twelve-step call stuff. Just people who can’t get it together, me and groups of other people who have been based in New York for a long time working with people who need help and reached out. It was about building communities around sobriety and staying clean and stuff like that. That was my focus since I moved to the Bronx when I was eighteen. I liked music, but I considered it to be a luxury. It wasn’t my primary focus: the other stuff was really my life. But no one ever . . . it’s not interesting.

No, it’s really interesting. So your social work was based on your own experiences?

Yeah, because I was an addict who got clean.

As a teenager?

Yeah.

So obviously it must have informed your music.

Yeah, it’s been my main influence, I would say.

Well, I watched the video for “Ride”, and I was truly fascinated. To me, it felt so ‘wrong’ on so many levels, but that also made it truly transgressive because mere hedonism or being rebellious is no longer transgressive.

Yeah. Like, I remember it was the San Francisco Chronicle or whatever who wrote this huge thing about me being an anti-feminist. But the thing is, I don’t really have any commentary on the female’s role in society. It was the same with my first song that got big, “Video Games”. People had criticisms about it being submissive and whatever, but nothing I ever wrote had a message. It was just my own personal experience, and it’s the same with “Ride”. I believe in free love and that’s just how I feel. It’s just my experience of being with different kinds of men and being born without a preference for a certain type of person. For me, that is my story in finding love in lots of different people, and that’s been the second biggest influence in my music.

I was taken aback by how affected I was by the “Ride” video, because I felt it was really saying something important, in a sense. Talking about internal darkness, but not only accepting that within yourself, but the line in the monologue where you talk about actually being in a position to explore that—it’s very brave, actually.

Thank you. Well, one thing you learn when you do get sober is that complete surrender is the foundation for all good things to come. And I feel like that idea translated to all aspects of my life. When you have absolutely no idea what’s going to happen to you or what your career’s going to end up like and you’re just really open to anything, then you don’t really have anything to lose. A lot of different people come in and out of your life. And it’s really fun to say yes, and it’s really fun to be easy about everything and just let songs come to you and let people come to you. And it is free, in a way.

Let’s go back to what you were saying about not necessarily having a message, because American themes and imagery, like the American flag, feature prominently in your videos and your music. Although to my mind, it could be seen as a dark side of America.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t love any fucking film or book that wasn’t based around the underbelly of society. I’ve always loved that. But on the other hand, I’m kind of simple in the way that I love the movement of a super-eight flag waving in the wind. The same with the palm trees and that sepia color of the fifties film. Like a lot of my choices had to do with the grade of the film. It was that simple, purely aesthetic. Same with my interest in photographers and things like that. A lot of it is just the look of it. I just like it.

Do you consider yourself patriotic?

Not anymore.

You were still living in America when Obama took over. Did that change things for you?

The first election? I was happy for the American people because he was a symbol that they needed to feel better.

Do you have opinions on healthcare reform or . . .

I have a lot of political opinions.

Yeah? Let’s hear some of them.

I get a lot of grief for just talking about my own musical choices. I don’t usually talk about my views these days that much on politics.

Do you consider yourself to be political?

Yeah, definitely.

Shortly, healthcare.

Well, it’s complicated because everything has changed for me. Before I had no money. And now everything I make, I lose. So I don’t have money again, because I lose half. Healthcare reform—that needed to be addressed. I still don’t have health insurance because I haven’t been back to the United States since the time when I couldn’t afford healthcare because it was seven hundred dollars a month.

Okay, let’s talk about feminism. What’s your take on feminism?

To be honest, I don’t really have one. I have a great appreciation for our world’s history. I learn from my own mistakes, I learn from the mistakes we’ve made as a human race. But I think we’ve gotten to a good place as women and we’ll just keep naturally progressing. That’s kind of how I feel about it.

Is it true that you left the US because you felt oppressed and unloved by the American media?

[laughing] Well, no one was really asking me for interviews, so there wasn’t really a reason to stay. Musically, I wouldn’t really work there because I wouldn’t know where to sing. I had a million shows lined up here, so that’s kind of why I went. And I didn’t really have any shows there. I mean, I could play on Sunset Strip and stuff. I could go back to New York . . .

I’m sure you could line up some shows now. How does moving abroad affect the way you feel about America or being American?

I think that my love for America has now become contained to the more specific things I appreciate about it. Like driving up the coast from Santa Monica to Santa Barbara—simple stuff like that. In terms of what I maybe thought it stood for, I don’t know.

You’ve already said that a lot of the imagery was driven by aesthetic choices, but how did exploring the dark side of America affect the way you explore the theme of Americanism?

That’s a good question. I actually find myself not going back to those themes in my writing in the last thirteen months.

So I suppose that’s something we’ll see the result of soon?

Yeah, definitely. I think it’s kind of pushed me back to really early influences. I still love the way I felt when I first found Allen Ginsberg and how much he painted with his words. And he was influenced by the American underbelly, but now, rather than me being influenced by my passion for the country, I just feel good when I listen to Jim Morrison. I feel good when I go back and read some of the Beat poets. But other than that, I don’t feel like, “Rah, rah, America!” Fuck that shit [laughing].

What are some of the new themes, you think?

Well, I graduated with a metaphysics degree and I loved philosophy, I’ve kind of gone back to things that made me feel excited about learning maybe six years ago when I was in school. And I have a boyfriend I really like, I write about him a lot. That’s really it.

I’d read that you’d studied philosophy. Was there a certain school of thought that really interested you?

Well, I mixed it with my studies in theology, because it was the best school for the Jesuit faith and all of the Jesuits taught philosophy classes. There was just a lot of talk about going back to that basic question: Why do we exist? How did reality come to be? Why do we do what we do? And how not to become the butcher, the baker, the candlestickmaker, the guardians of the middle-class—that really interested me. I don’t know. Yeah, I loved being around people who wondered why we were here.

Do you still pay attention to what’s happening with the Church? Like, the new pope?

Yes, I’m aware. I wish him all the best.

And what do you think of the Church sex scandals?

It’s hard to see other people’s bad choices ruin the mysticism that can come from inside the walls of a church. It’s unfortunate. I don’t really understand why certain groups of people are drawn to that profession. I was talking to my mom about that.

For the latest EP, Paradise, would you say there was a creative change in your approach to songwriting?

I was in a better mood, staying in one place in California. It was kind of a summing-up of the idea of living at the Chateau Marmont—and then I moved out. It was just kind of a closing door. I like that it feels more lush and tropical, and I like that it has more of a Pacific Coast sound at times, like “Gods & Monsters”. Paradise is my favorite record, I love it.

Does it have anything to do with working with Rick Rubin?

No, I only worked with him for six days, because he only worked on “Ride”. But I worked with the same guys I worked with for Born To Die. I’ve only ever worked with those guys. Emile Haynie, he comes in at the end, and then there’s Rick Nowels and Justin Parker who write the music underneath the songs. I write the words and melody and they write all the chords and music. And then Dan Heath comes in for the string arrangements, after which Emile puts in the beats and soundscaping, like birds and bells.

Emile Haynie worked with Eminem and Lil Wayne, right?

Yeah.

You’ve described yourself in the past as “Lolita lost in the hood.”

[laughing] I was fucking around with that journalist.

I thought it was funny. But how does the idea of “hood” fit in to what you do?

Well, I lived in the Bronx for four years. I lived in Brooklyn for like four years after that. I always consider myself to have a serious street side, even when I was in high school. I mean, I was pretty crazy. Everyone I knew was really crazy.

Why’s that?

It’s just the way it was.

Is it because you lived in a small town in upstate New York?

Yeah, probably. It was boring. That town is crazy, too. I was a bad girl, but I’m good now. I guess I have some bad tendencies. I don’t like to do hurtful things, but I am drawn to the wild side. I love riding motorcycles; I love rollercoasters; I do like adrenaline. But I’ve also found true happiness when I was living in New York and working with other people in that way that we’ve talked about. So, I don’t know. But I don’t feel at odds with it.

The “hood” thing relates to the underbelly thing, but in your case it kind of comes across as a “white trash” hood in terms of the image you project, especially in the “Ride” video—though probably not in your real life. But it’s also related to the choices you make and the producers you work with, because they work with rappers, who are artists more likely to be associated with the notion of “hood“.

I did move into a trailer park when I made my first record. I got ten grand from Five Points Records and moved into Manhattan Mobile Home in New Jersey. And I was happy, because I was doing it for myself. There was a white trash element in the way there was a time that I didn’t want to be a part of mainstream society because I thought it was gross. I was trying to carve my own piece of the pie in a creative way that I kind of knew how. And I thought it was cool to be living by myself and working with a famous producer. I was excited about the future at the time.

You didn’t want to be a part of mainstream society, mainstream America, which I get. And now?

And now, still, I’m in my own world. It’s kind of like neither here nor there—musically and socially, and whatever. Me and Barrie [-James O’Neill, her boyfriend from band Kassidy], we don’t have too many friends in music, or people that we know who are kind of doing the same thing. We do our own thing. It’s all about the writing. It used to all be about the service work through the drug and alcohol rehabilitation, which I haven’t worked in in two years now. But it’s always been about the art.

You don’t feel you have a group of people in music who you necessarily connect to—a scene, let’s say, or a group of peers? What you talk about publicly and in interviews—say, listening to the The Doors or Dylan—it all seems “normal”. But I think what you do is not normal, actually.

Well, I thought so, too. I thought my tastes and likes were pretty normal, but then I met everyone and I was like, “These people don’t actually care about music and art. They want to be cool.” I never met anyone who cared about music as deeply as me and my boyfriend, or who really cared about poetry—who really lived it and breathed it. I haven’t met anyone so far. I just can’t affiliate with those people.

But didn’t you say at one point that you weren’t even interested in putting out another album?

I’m not that interested in putting out another album.

But you are working on your follow-up?

Well, I work on music, but I don’t have a time when I would release it or anything. I could play you some stuff. Want to hear it? [Starts playing new tracks from laptop]

Yeah, of course. Are you working with your boyfriend on music?

Yeah, some of it. And he’s great.

Almost every song on Born To Die is in the second person, the same goes for Paradise. To what extent is it all addressed to the same person?

It depends. It’s just like a general, spiritual collective. The ether. I have certain people. It’s more like times. Like when I was working with my first producer David Kahne and I was in that mobile home for two years. I was between there and Williamsburg and I had a boyfriend then. It was a very happy time and I reach back to those memories for my writing, so sometimes to people. But I would never tell them or talk to them about it. But I have a distinct version of the way things went.

So are you also going to work with the same team for the next record?

Yeah.

I thought the sound developed quite a bit from Born To Die to Paradise.

You did?

Yeah, I thought Paradise was much better.

Yeah, I thought it was better, too.

There’s a lot of darkness and pathos, I’d say.

Yeah.

And that’s not changed, from the sound of what we’re listening to now.

No. Things have still continued to not be easy, even with the ways that they should have become better. They’re still really hard, which I think has been my theme in life: trudging the road to happiness. Definitely a happy destiny, it’s trudged.

Well, happiness isn’t a static state. It’s an active state. That’s the ancient Greek definition. It’s not a state of rest—it’s a process.

Yeah.

For me, there are moments of pure happiness, but you can’t achieve that over a sustained period of time. It’s just you try to make those as many as possible.

Definitely. And I mean, it sounds really strange, but just in general, I have found that devoting your life to the people around you and caring for them is the true road to general happiness.

Why is that strange?

Well, I mean, people aren’t going to understand. Trust me. But I’m just saying, in my experience.

Well, it does seem kind of sad, it is almost as though you can’t do anything right.

Yeah, oh it is sad. Trust me. It’s not fair.

And do you think that’s a feminism thing? Or would you say an anti-woman thing?

[laughs] No, I think it’s an anti-me thing. ~

Thanks to A.J. Samuels.

Published June 18, 2013. Words by Lisa Blanning.