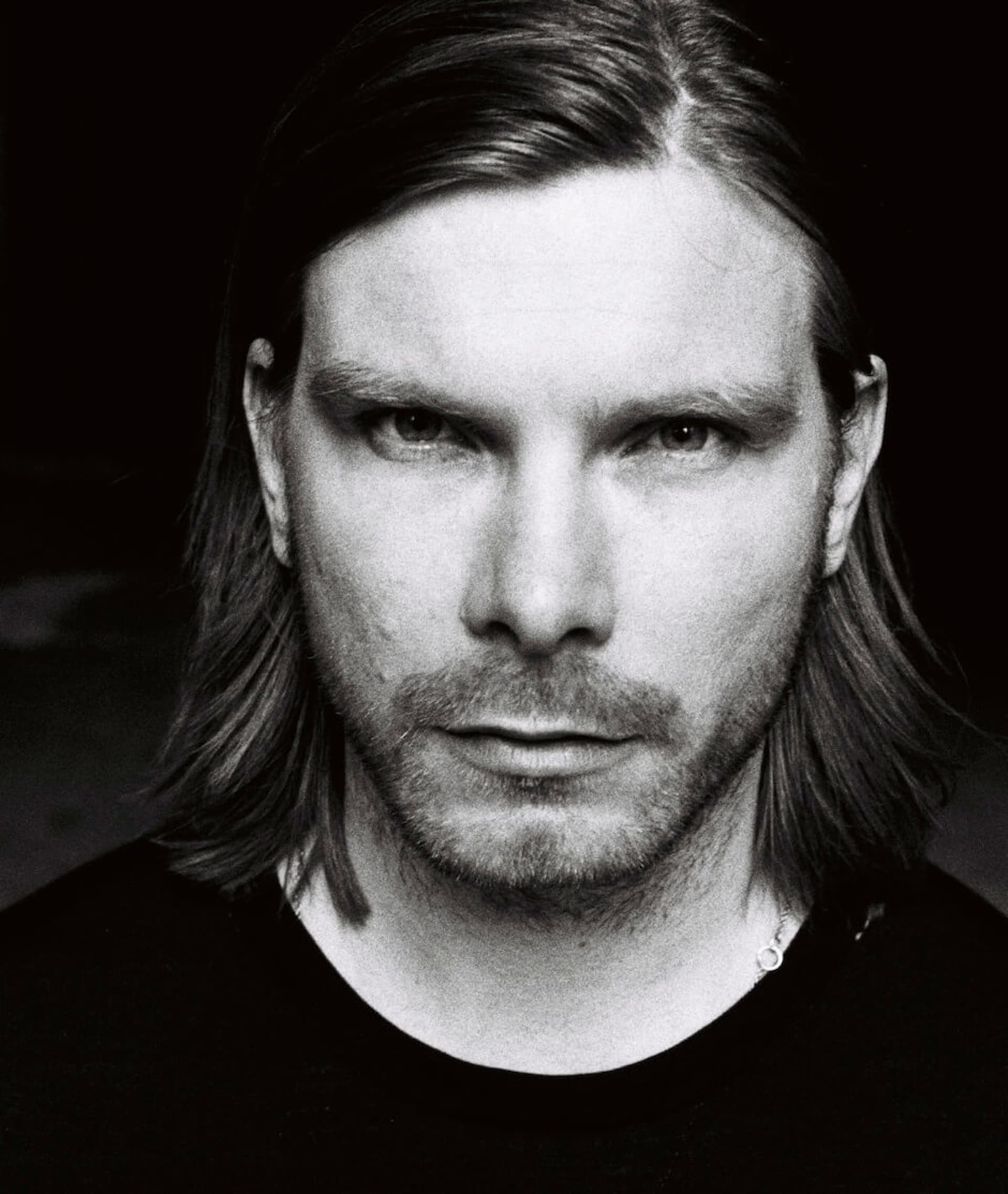

Last Man Standing: An interview with Marcel Dettmann

This week sees CTM kick off its annual winter residency at the center of Berlin’s cultural world. Among the deluge of events which push at the seams of electronic music and performance, it’s the Berghain blow-out helmed by Marcel Dettmann that promises to be a showstopper. We caught up with the Berghain resident whose marathon sets are the stuff of techno lore to talk excess, anarchy and playing drones to excited tourists.

“For me, it’s Berlin, Berghain and Hard Wax which created me,” explains Marcel Dettmann, speaking in his home studio located in a leafy corner of Prenzlauer Berg. And if those three points can be taken as the trinity of techno, where does that leave Dettmann? As one of the residents of Berlin’s monolithic clubbing institution, Berghain, his unholy communions on Sunday have become notorious, running up to twelve hours straight and powering well into Monday morning. If you can endure it—and the Crossrail sized hole you’ll bore into the following week—it’s as close to redemptive as clubbing gets. But you’ve got to be tough.

Growing up in Fürstenwalde, a suburban town fifty-five kilometers east of Berlin, Dettmann has more than a little East German resolve; he was just twelve when the Wall fell. The tumultuous period that followed was the backdrop for his musical coming of age. It’s not too much of a stretch to see how this period of aggressive upheaval, alongside the aggro EBM which soundtracked his hormone-powered teenage years, has hardened into the concrete foundation of his own productions. While his second album II expanded on the unadulterated techno formula of his 12-inches and unforgiving first record Dettmann, you can still tell a Dettmann record by its savage economy of elements and industrial sweep. When he plays Berlin’s CTM Festival next week, in the relatively alien habitat of Panorama Bar, he’ll be taking on international representatives of 21st century techno. Who’ll be the last man standing? Take a guess.

You’re playing CTM next week, also on the bill is Helena Hauff, Concrete Fence and Dasha Rush so it feels like it’s bringing together some divergent strands of techno being made in 2014. Does it feel like a particularly fertile period for techno for you?

I’m really looking forward to it—I’m looking forward to seeing Actress, Helena who’s from Hamburg and I’m really liking what she’s doing the last couple of years, I’ve got some records from her. It’s a nice mixture of characters in the electronic music scene. It’s gonna be my first time playing at CTM and it’s also special because I don’t often play at Panorama Bar, normally I play at Berghain.

Will you be restricted by how long you’ll get to play, you’re known for your really long sets at Berghain. Or do you sometimes welcome these limitations? Have you got anything planned especially for CTM?

Sometimes, like in this case playing three to four hours—I think it’s good to be restricted. The special thing for CTM is like I said Marcel Dettmann playing in Panorama Bar. And on top, it’s my first gig after my holidays.

Of course, your connection with Berghain goes right back to before it was even Berghain—to its forerunner Ostgut.

I remember when I went there as a young kid for a party, I remember when they opened from ’98 – ’99, it was New Year’s Eve and it was my first time there. It was ninety percent guys and ten percent girls and there was 300 people or something. It really reminded me of E Werk—I really liked that club back in the day. A friend of mine gave the owners a mixtape of mine and they asked me to play there, I was only twenty or something, so really young. It was not my starting point as a DJ because I DJ’d before in my hometown or in other cities in the east part of Germany: Dresden, Leipzig. However, that was the starting point for Marcel Dettmann. Then I got into the Berlin scene.

What was that like, compared to the international scene now?

It was totally different. In the beginning it was really a gay club, and I really loved that, they really wanted to dance and party and you felt there was such a great energy. After a while Panorama Bar came up, and then it became more international, people from New York, people from London, people from everywhere in the world came to this club—fashion people, actors, whatever. It got a more international vibe than. I can’t say that Ostgut was different to Berghain, it was a long time ago and I was much younger. For me though, it’s grown slowly. Nowadays, the New Year’s Eve party or the birthday party was amazing and I just realized again what we have here in Berlin. We wouldn’t have it without Ostgut, it’s the reason we have it now. Without it, the Berghain would have never existed.

In the Slices interview you did for EB you drove back to your hometown of Fürstenwalde and the impression you got was one of an ex-industrial town, with factories and tower blocks shaping the skyline. Did you feel like the atmosphere fed into your musical identity? So much is said about techno in Berlin being closely related to its topography after the wall came down.

It was a special time, I was twelve when the wall came down. How Berlin looked after the wall, with all these old buildings, it looked like the Second World War had just finished. And there was an anarchic feeling because the West police and the East police didn’t know whether they should do something or not. There was some crazy stuff going on in the streets, like fights between punks and Nazis. It was a crazy time actually, really weird, a lot of gang fights. I think that could be a reason, of course. I’m definitely not a flower power guy! It was a rough, tough time and it was tough growing up then—we would hear stories about people dying. It was a rough political system, but I didn’t realize that then. It was in the days after the wall came down when violent change happened. I’m happy that I wasn’t older; when you are sixteen and you’re going to work, to have your company you work for no longer exist. I was at school, I was a kid enjoying my childhood. Around Berlin it was really tough, in Berlin it was worse, in Marzahn for example… Crazy, don’t stay there when it’s dark.

Interesting, then, that a word that comes up a lot when describing your music is “uncompromising”. Often, your records feel so austere, so reduced that if you subtracted one more element the whole track would collapse. It’s not easy music.

It’s difficult to explain. It’s a feeling. It’s inside me. I don’t have any formula. The school of music, of making records and DJing which I come from, is darkwave, EBM, and that is also really uncompromising. It’s really harsh, a really harsh rhythm going on, some people screaming into the mic, like Nitzer Ebb for example, it’s really like, “Wow,” I get goosebumps. When I was much younger, the way we danced was so… testosterone-fuelled. I was thirteen or fourteen, you needed something like this, so that’s where it comes from. Then I started going to clubs in Berlin and getting more into techno and the Hard Wax crew and doing things, like for example, what Basic Channel did, making a couple of records and then saying that’s it, nothing more to say. Yeah, this is my school.

Did growing up in the DDR limit the music you were exposed to or were you too young to be affected by that kind of cultural influence.

I remember this neighbor who lived next door who had this double-deck tape recorder and we recorded our music off the radio, for example Depeche Mode, Yazoo, Madonna, whatever was famous at this time. I remember we recorded a Depeche Mode concert before the wall came down. Then we would make copies, that’s how I started getting into music. I think it was because he was three years older.

How did you go from there to your first techno records? Was it through the same guy?

That was a brother of a friend, he introduced us into EBM and dark wave that was really independent, underground stuff, the kind of music you didn’t get in every record store. He gave me CDs and samplers and tapes and stuff, and then in 1992 he came up with a compilation. I remember it was a trance compilation. I actually found the CD recently. It was called Logic Trance, Logic was the label. I actually listened to it again and thought, “Wow, this is still real good stuff.” When I think about trance now, I think about cheesy music, but trance could be really mental. I love the mental vibes and stuff, it’s not just a physical thing. From there I got deeper into techno. I started going to Tresor where they played more Berlin-Detroit-Chicago kind of stuff.

And Tresor would’ve been the hardest, toughest techno back then, right?

Yeah, but I really liked it. Not only the music, but also the spirit, when you got to the club and saw the people… The first time I was there, I thought the Berlin people were really crazy.

Why did you think the Berliners were crazy?

They were maybe all on drugs but I didn’t know—I was so young! I was like, “Oh, Berlin people are really crazy”. It was weird. Then, after a while I began to buy techno 12-inches, then when I was fourteen I had my Jugendweihe, which is like a religious confirmation but secular because in East Germany we’re not religious. You get money from your family and some people, buy a bike or something like that—I bought a Technics turntable. I had that Technics and I had a turntable without a pitch controller, and I got a mixer from my teacher in the school, without headphone plugs, and then I started mixing. I didn’t know how they did it, I didn’t know that they used headphones to beatmatch and pitch them, I knew none of that. I just mixed the breaks. For me, it was just the greatest thing, mixing my favorite music at home and making mixtapes.

It seems that Berghain, as the locus for techno in Berlin, has really colonized the way that we talk about and understand techno right now. People who have never been there have this idea of what it is; when people discuss it they reach for the ‘Berghain’ descriptor in a way that they wouldn’t with any other club. What’s it like observing all this from the inside?

For me, I’m a resident, I’m playing for the guys for fifteen years now, so of course I have a different view on this. But it’s great that people look forward to something they do not know, but of whom they have heard a lot…

I wonder if it’s wish fulfillment. People have an ideal of Berlin and, by extension, Berghain and they want that ideal to be true. There’s all those mythical stories about Berlin back in the nineties and people have fear of missing out, they need to believe it’s still like that and they’re part of something.

Yeah. And it is really great to play an opening set to see people come into the club and I’m just playing drones, just starting the night, and the people walk in like [throws hands in the air], “YEEAAAHH!” These are people maybe from South America or wherever and they’ve just come to Europe, to Berlin, to see Berghain and theyget in. It’s a great thing for them. That’s the reason you have this special atmosphere there.

Do you think there’s something special about playing the end of the night? It seems that the bond of trust between DJ and crowd is at its strongest. Not that I’ve ever stayed at a Berghain party until “ende”, although I’ve tried.

[laughs] Yeah, it’s special. When you are tired and relaxed, because it was a long weekend—me too! I come from somewhere and then it’s really special, you have time. You can start at any point you want and take the crowd up or bring them back down. Actually, now the nights end Monday morning at 10 a.m. or something, which is so weird. I remember it used to end on Sunday and now it closes to a day later. It’s special but it’s tough sometimes. When you stay there for twelve hours, it’s really tough. When you come home you are tired for two days—really, really tired. But it gives me power to be there. You just realize, when you finish, how tired you are. It’s like a drug, it keeps you alive and then after… You fall into a hole. Mondays never exist. Tuesdays, also.

And you’re just drinking?

Yes. Just drinking.

It’s interesting that you say it finishes a lot later now. Do you think there’s a hunger, a need almost, for more, to test the boundaries of losing yourself? Where does that stop? Are people more excessive now than they were in the nineties?

I think it was always like this in the electronic music scene. People want to escape from their every day lives so they just continue… and keep on going…

You’ve got a two year-old daughter. Did having her change you with regards to the music you make and the hours you keep?

I’m not really sure. She changed me of course because now I have a different focus, it’s the music and my family, of course. Last week I actually had the first three days with my daughter alone cause my wife was away. I really enjoyed it, it was so peaceful. I didn’t think about anything else. But I don’t think it changed my musical taste and musical mind a lot. It still comes from [puts hand on chest] here. ~

Marcel Dettmann plays CTM 2014 with Actress, Concrete Fence, Metaslice, Dasha Rush and Helena Hauff on Friday, 31st January at Berghain/Panorama Bar.

Published January 21, 2014. Words by Louise Brailey.