The article you’re reading comes from our archive. Please keep in mind that it might not fully reflect current views or trends.

The Legacy Of David Mancuso By Tim Lawrence

Of the many paths that led me to David Mancuso, the final and most direct one came courtesy of Stefan Prescott, the co-owner of Dance Tracks. I was a Friday night regular at the store from 1994 on, having moved from London to New York to get closer to the city’s house music scene and enroll in the doctoral program in English Literature at Columbia University. My somewhat unbounded enthusiasm for dance culture had prompted a professor to suggest I write a “quick book” on the subject, and after landing a contract to write a history of house music, Stefan recommended I interview David, simply because David had been around since the beginning.

Preparations for the interview were halting at best. Later on I would track down two significant interviews with David: one conducted by Vince Aletti in the Village Voice in 1975 and another by Steven Harvey in Collusion in 1983. Yet neither were suggested to me as I asked about David’s influence and received puzzled shrugs in reply. Concerns that the interview would turn out to be a waste of time increased when a writer who was on the cusp of completing his own book on house music and had interviewed a significant number of people for his research told me that there was no real need to speak with David. Although he had cultivated a unique audiophile sound system, he exerted no obvious influence on the wider scene. But by then I’d set up the interview and resolved to go ahead with it just the same.

David and I met in a homey Italian restaurant in the East Village in April 1997. For three hours, I battled to track what he was saying as he reeled off a miasmic rush of names, parties and sounds that were almost entirely foreign to me (the exceptions were Larry Levan and the Paradise Garage). I tried to keep a grip as David insisted that I begin my account not even with disco but instead the pre-disco dance scene that began in early 1970. I quickly sensed just how much time I would need to straighten out David’s tangled story. I also realized that even if it was only a quarter true it would still transform our understanding of the history of dance culture.

David’s investment in civil rights, gay liberation, feminism, the anti-war movement and the broader countercultural movement was immediately transparent, as was his commitment to having his parties contribute to a more equal world.

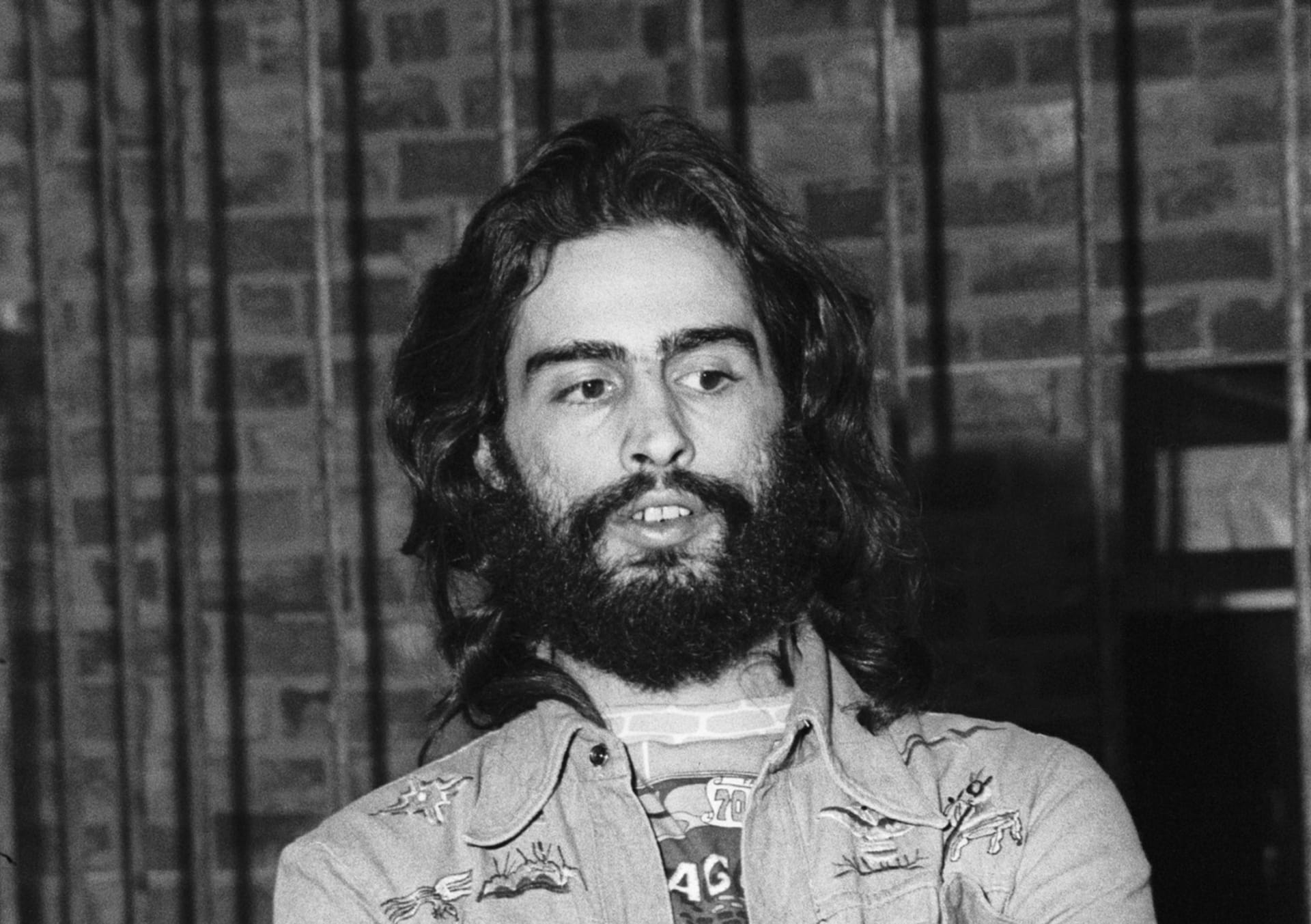

I also liked David a great deal. A cross between a disheveled vagabond, biblical prophet and cuddly bear, he was atypically passionate, philosophical and political. He led me to immediately wonder if I’d ever met anyone whose discussion of dance culture was so firmly rooted in ideas of community, integration and social potential. David’s investment in civil rights, gay liberation, feminism, the anti-war movement and the broader countercultural movement was immediately transparent, as was his commitment to having his parties contribute to a more equal world. Even if the countercultural movement found itself on the defensive by the end of the 1960s, David was clear that the movement’s energies could take root and flourish in his party setting. We ended the interview with a hug and a commitment to continue the conversation.

I later came to understand that what happened next was absolutely central to David’s outlook on life. Five messages were waiting for me on the answering machine by the time I got home, all of them from people David had contacted after the end of our meal. I liked that he felt enough of an affinity to accelerate the communication, yet didn’t grasp how, having grown up in a children’s home, he had come to invest the same level of trust in friends that many reserve for families. He could only think about doing something if he did it with friends, who formed the bedrock of his life and his party philosophy.

As the interview with David unfolded, I attempted to hold on to the idea of writing a history of house. Meeting up with legendary figures such as Frankie Knuckles, David Morales and Tony Humphries, I asked each of them if—and I acknowledged just how improbable this might sound—they had heard of or even knew a somewhat outré guy named David Mancuso and a party called The Loft. As if pre-programmed, all three launched into a mini-speech about David’s profound influence on their formation and about the way they had learned about the power of music and dancing on the floor of The Loft and about how they even sought to bring David’s sensibility into their work as DJs. When I fed back the surprise acclaim to David, he was a little underwhelmed and wondered out loud why they had fallen out of touch. The quality of human interaction was always uppermost in David’s mind.

During this period I went to my first Loft party, held at a new space David had recently moved into on Avenue B, having bounced from home to home after losing his final main location on Third Street. (Previously he staged parties on Broadway and then Prince Street.) I remember acclimating to the unusual environment: a low-lit home that was largely dedicated to a dance floor flanked by tall stereo speakers and a lavishly decorated DJ booth. David occupied his own strange space within this strange space. He barely responded when I said hello, as he was already deeply immersed in the sonic and psychic space of the party. Slightly disturbed by his affectless presence, I struggled to tune my ears to the gentle sounds emitted by the speakers. By 1 a.m. there might have been a total of six people in the room.

David’s commitment to fundamental principles rewarded him with a room packed full of an ecstatic dancers by the time of his anniversary party the following February; that night I began to grasp what The Loft must have been like during peak years in the 1970s and early 1980s. But a short while later David was forced to start all over again when the friend from whom he was subletting the space defaulted on the rent. This marked the moment when David was forced to vacate the last home that was spacious enough for him to throw a party, which in turn suggested that The Loft had come to an anticlimactic end. David seemed to go downhill during this period, and there were times when he became harder to reach. It seemed incredible that the person who was beginning to seem as though he might turn out to have been the most influential figure in the history of dance culture had reached the point of losing everything.

The Loft—a name attached to David’s parties by his dancers—inspired generations of people who looked to emulate and disperse its transcendental message.

David’s contribution to dance music was profound. Even though he thought of himself as a musical host, he helped to pioneer the democratic and conversational principles of contemporary DJing by picking out records in relationship to the energy of his dancing crowd. His efforts were paralleled only by Francis Grasso at The Sanctuary, yet whereas Grasso focused on mixing between the beats, Mancuso explored the parameters of an expansive musical set and brought the next record in via a brief segue or, from the early 1980s onwards, dropping the practice of mixing altogether. With time on his hands and counterculture as his compass, David also introduced a panoply of records, many of them long album cuts, that stretched out the sonic as well as social parameters of the party.

The Loft—a name attached to David’s parties by his dancers—inspired generations of people who looked to emulate and disperse its transcendental message and community ethos. The owners of the Tenth Floor, Gallery, Soho Place, 12 West, Reade Street and the Paradise Garage modeled their venues directly on the Loft, while Flamingo and The Saint were also intimately linked to Mancuso’s party, given that they had been modeled on the Tenth Floor. Over in Chicago, Robert Williams had been a Loft devotee before he opened The Warehouse. Meanwhile DJs Nicky Siano, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles followed by the likes of Tony Humphries, François Kevorkian and David Morales spent formative years at The Loft before they went on to become scene-setting figures in their own right. David also co-founded and became the most prominent figure in the New York Record Pool, the first organization to arrange for DJs to receive free promo records in return for feedback and dance floor play. At times it seemed as though all paths led back to the Loft.

David faced challenges during The Loft’s peak years. After being forced by city officials to vacate his Broadway home in 1974, he endured a titanic struggle to re-open on Prince Street. Yet his biggest crisis came after he moved to a new space he had purchased on Third Street in Alphabet City, having been served notice by the owner of the Prince Street building, only to witness Ronald Reagan cancel plans to regenerate the destitute area. The move immediately cost Mancuso two-thirds of his crowd and, although he made a partial recovery, a trail period came to a close when he lost the building altogether. But early into his time on Avenue B he broke the habit of a lifetime and agreed to play outside his home—in Japan—in order to raise funds to purchase his new residence. The trip didn’t go as planned but it at least introduced him to Satoru, the owner of Precious Hall in Sapporo, and with a new friendship established David began to make regular trips to Japan, forging Loft-like conditions and relationships along the way.

The Japan experience encouraged David to subsequently travel to London to mark the release of his David Mancuso—The Loft compilation on Nuphonic Records, and following that one-off party he contacted me and Colleen Murphy, a New Yorker living in London who had worked as musical host at The Loft, to ask if we would be interested in co-hosting Loft parties in London. With my friend and colleague Jeremy Gilbert joining the team and with Adrian Fillary and Nikki Lucas also contributing to the first cycle of parties, David devoted himself with improbable energy to make his party vision work in a second faraway city. True to form and against standard practice, he requested a relatively modest fee in exchange for staying five nights rather than one night in London, because that way he could start to form deeper friendships that would find expression in the party.

From the get-go David was obsessed with building the best possible sound system for these parties. I accompanied him as we hired equipment that invariably left David dissatisfied, and I also dealt with the sound system guys who would sometimes have tears in their eyes as David tore into not only their gear but their very understanding of sound reproduction. With the situation unsustainable, Colleen, Jeremy and I agreed to divert the significant sum of money we were spending on hiring the best possible equipment into a loan that would enable us to purchase David’s preferred equipment. We’d already managed to buy a set of high-end Japanese Koetsu cartridges. Now Klipschorn speakers and other paraphernalia followed, with Jeremy overseeing the process and David working every possible favor on our behalf.

“To Larry Levan, David was a quasi-mystical figure with supernatural power because David was so dedicated to providing people with the ultimate experience of the song.”

David had already dedicated most of his adult life to creating a sound system that would maximize the experience of dancing to music. During his time on Broadway he asked sound engineers Alex Rosner and Richard Long to respectively create tweeter arrays and bass reinforcements so that he could accent certain records at key moments during the night. This innovation came to transform the way sound systems were designed and installed all over the world, yet David, constantly restless, ended up ditching these new components on the basis that there was no need to interfere with the balance of the original recording if the playback equipment was of a sufficient quality. Many, including Larry Levan, looked on and learned. “To Larry, David was a quasi-mystical figure with supernatural power because David was so dedicated to providing people with the ultimate experience of the song,” François Kevorkian, a close friend of both David and Larry, recounts in Life And Death On The New York Dance Floor. “Larry understood how deep David went in order to focus strictly on the essential part of the music, which was to play the song in the closest possible form to the original recording without adulterating it in any shape or form. Although you could get a lot more bass and sound pressure when you heard a record at the Garage, at the Loft every single detail and quality would come through.”

Nevertheless the sound system remained just one element in The Loft ecosystem, and relatively early into our run I began to wonder about London’s ability to reproduce one of the finer yet absolutely critical aspects of the New York City parties. On the one hand, David was committed to divesting himself of his ego in order to enhance the communal experience on the dance floor. On the other, David’s tendency to disappear during his own parties came under pressure as dancers began to see David as a legendary figure bestowed with shamanic power. The issue had been contained in New York, where Loft dancers had long been trained to focus on the floor rather than the booth, but in London dancers were long into DJ worship, and with David’s reputation growing in the slipstream of the Nuphonic compilation, the 2004 publication of my first book, Love Saves The Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-79, and the accumulating renown of our parties, there was no straightforward way to encourage them to shift their attention to the communal floor. Some even began to point phones in David’s direction, leaving him feeling distinctly uncomfortable. We put a stop to the cameras and phones, yet the tendency towards “DJ adulation” remained a concern.

The conundrum seemed fundamental, and I kept thinking about the time I asked David about the principles of preparing for a party. He had replied that the party could only begin when a group of friends decided that they wanted to find a place where they could dance. The next step required them to find a space in which they could relax, be intimate and party. After that the friends needed to assemble a sound system that emphasized the musicality of any recording. Then they could send out invites to others, with each friend allowed to bring a guest so new relationships could build, as well as begin preparations to decorate the room and provide wholesome food. Only then might the friends start to think about someone who could select music that would be attuned to the taste of the gathering. It followed that if the musical host was the least important part of the jigsaw that component should be the easiest to replace.

During an interview I conducted in 2007, David further explained his philosophy. “I’m just part of the vibration,” he replied. “I’m very uncomfortable when I’m put on a pedestal. Sometimes in this particular business it comes down to the DJ, who sometimes does some kind of performance and wants to be on the stage. That’s not me. I don’t want attention. I want to feel a sense of camaraderie. I’m doing things on so many levels that, whether it’s the sound or whatever, I don’t want to be pigeonholed as a DJ. I don’t want to categorized or become anything. I just want to be.” He added: “There’s a technical role to play, and I understand the responsibilities, but for me it’s very minimal. There are so many things that make this worthwhile and make it what it is. And there’s a lot of potential. It can go really high.”

As far as David was concerned, The Loft simply took its position in a universal dance that dates back to the beginning of time.

It was within this context that I started to wonder what would happen if David’s philosophy were put to the ultimate test. Would the parties still work if the reticent musical host didn’t show up? Would the energy be just as strong?

The test arrived when David flew in to London, became sick and confirmed on the morning of the party that he was too ill to attend. We agreed that Colleen should step in. We also agreed to offer David diehards the option of a full refund. Although she had next to no time to prepare, Colleen fulfilled her musical hosting responsibilities in a way that thrilled the dance floor, in part I suspect because we all realized at this moment that the parties could not only survive but also flourish in David’s absence. David was correct—the Loft party could run without him being present.

It is easy at this time of loss to eulogize David Mancuso as the sole originary source of party culture. That theory should be supported over all others, because the Loft ultimately went deeper and long survived parallel developments at other early discotheques. Yet it’s important to remember that the uncannily insightful party host has never been comfortable with the idea that he started anything, which helps explain his earlier absence from histories of dance culture. As far as David was concerned, the Loft simply took its position in a universal dance that dates back to the beginning of time. Entering the cycle, he simply drew on various practices—the age old history of social dance, the rent party tradition, hi-fi sound, the downtown loft movement and Timothy Leary’s LSD parties—and folded them into a new situation that was really a very old situation. As Jeremy Gilbert recalls: “David made this remarkable observation to me once, that he sometimes thought there was one big party going on all the time, and occasionally we just try to tune into it.” It’s precisely in this way that David saw the Loft as a microcosmic element that contributed to a much larger, universal continuum.

In a further demonstration of his innate philosophical sophistication, David was equally uncomfortable with the idea of endings. When it came to the point where he was required to vacate Prince Street, partygoers started to refer to it as the “last party,” but Mancuso refused such terminology and instead wrote a letter to his invite list that spoke of the party moving to a new venue after June 9, 1984. “We wish to develop a Loft foundation whose primary function would be to ensure the Loft’s continuation for years to come… more on this later,” he added. Bouncing back from the loss of Third Street and Avenue B, Mancuso enjoyed a halcyon period of community partying in three countries, yet started to confront the question of another ending eight years ago when he turned 64—a symbolic age for any Beatles fan. How long would he continue to travel or indeed continue to throw parties in New York? How would a body, not always cared for, hold up under the strains of international travel and the challenge of hosting eight-hour parties in New York City?

A doctor addressed the first question by telling David that he should hold back from international travel after a health check produced results that suggested a need to slow down. The news came as a shock to us in London, and I can imagine the experience was similar in Japan, yet we had already reached the point where the parties could run independently of David. So a near-seamless transition took place in which a group of thoroughly inducted Loft devotees knew exactly how to continue David’s party philosophy in the absence of its pioneer, fulfilling David’s ultimate ambition for his party. As for New York, David enacted an incremental withdrawal until there came a point when, almost unnoticed, he withdrew from it altogether—in body if not in spirit.

The New York Loft party of last October confirmed that it had reached the point its London and Japanese counterparts had been forced to arrive at more abruptly. David was nowhere to be seen, but his philosophical outlook could be felt everywhere, from the gloriously detailed sound to the diversity of the crowd to the warmth of the room to the ecstatic energy of the dancers. David had achieved something that no other party host has come even remotely close to achieving. He was the founder of a party that had been running for 46 years, and he had co-founded parallel parties in Japan and London that had been running for 16 and 13 years, respectively. What’s more, the core principles upon which all three parties had been established meant that each party could function without David’s presence. There would, it transpired, be no ending. Even if David missed going to his own parties, he could rest in the knowledge that he had tuned into the “one big party” in an utterly profound, inclusive and enduring way.

Many of us sensed that David was slipping away during the months that preceded his death. Knowing he was experiencing some difficulties, I started to wonder how he was holding up when he didn’t get around to proofing the extracts that referenced the Loft in Life And Death On The New York Dance Floor. I called him several times to try and at least confirm his quotes with him before the book went to the printer but he sounded distracted, albeit happily distracted. I was left with the impression that he was slowly withdrawing from a world he had done so much to shape.

Shortly before I travelled to New York to launch the book, David surprised me by calling to say that he would like to meet up with Colleen and me around the time of the October party–because I was supposed to attend with the new book and David had invited Colleen to share the responsibility of musical hosting with Douglas Sherman, who had been asked to carry that responsibility more or less alone after David began to step back. But no date was placed in the diary, and during the ensuing Loft party I became concerned when Elyse, one of David closest friends, mentioned that David wasn’t only staying away from his own parties; friends weren’t getting to see him at all. I called David several times during a hectic trip but was unable to get past his answering machine.

He came to see Loft dancers as part of his extended family, as if they were an extension of his upbringing in the children’s home, and he provided employment and even shelter to those who were most in need.

David was a family-minded person. Even though he was an orphan and experienced a disrupted upbringing, he remained as close as he could to his family and felt a particular affinity with Sister Alicia, the nun who raised him during his early years. He came to see Loft dancers as part of his extended family, as if they were an extension of his upbringing in the children’s home, and he provided employment and even shelter to those who were most in need. Every time I spoke with David he would begin by asking about my family before launching into incredibly intense conversations about how to improve some aspect of the party in London, with the focus almost invariably linked to making the parties more comfortable, or more homely. In London, as in New York, the group of dancers who came to together to make the parties happen soon began to relate to one another as if they were part of a wider family. When news broke of David’s passing it felt as though a family member had passed away.

It can now be concluded that David held on to a remarkably purist set of beliefs through to the day he died. Not once did he advertise a party. Not once did he run the Loft as a club. Not once did he work as a DJ. Not once did he go on tour. Not once did he play a bootleg. Not once did he compromise the dream of running his parties as a space where everyone was welcome as equals. Not once did he play music at a level that could damage the ears of his dancers. Not once did he select a record that he thought was less than optimal for the situation at hand. More than anyone I ever met, David understood the fundamentals of not only the party but also of existence. “David was not just a guru, but a satguru: not just a teacher, but a teacher of teachers,” Jeremy wrote after David’s passing.

In today’s compromised world, where space in global cities is in short supply and prohibitively expensive and where prevailing social conditions are almost entirely hostile to the bedding down of a vibrant, socially-minded party culture, it seems unlikely that another David-like figure will emerge. And yet these conditions and times have produced a scenario in which the importance of David’s life and work, his vision of the party and of music, and his theory of society and its potential for positive transformation seem more urgent than ever before. It’s as much as we can do to continue to attempt to understand his ideas and put them into practice.

David always insisted that The Loft stay rooted in community participation, audiophile sound and an expansive musical palate because the combination of the three would deepen the transformative potential of the party, which would in turn make a small contribution to social progress. This vision exceeded David’s being and will survive his passing, just as it will survive all of our deaths. That is because the dance, in the final instance, is embedded in the fabric of the universe, and it is therefore beholden to us to support that social energy when the opportunity arises. When we do so, our lives and the lives of those around us will improve. For we have learned nothing from David if we haven’t learned that, as he was so fond of saying, “music is love, and love saves the day.”