Art Collection Telekom Presents Dan Perjovschi on Ephemeral Forms

In anticipation of the Art Collection Telekom exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope, EB.net will roll out a series of seven short interviews with contemporary artists from Eastern Europe. They’ll all appear at the exhibit, which features a selection of works from Art Collection Telekom artists in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Fragile Sense of Hope opens at Berlin’s me Collectors Room/Stiftung Olbricht October 10 and ends November 23.

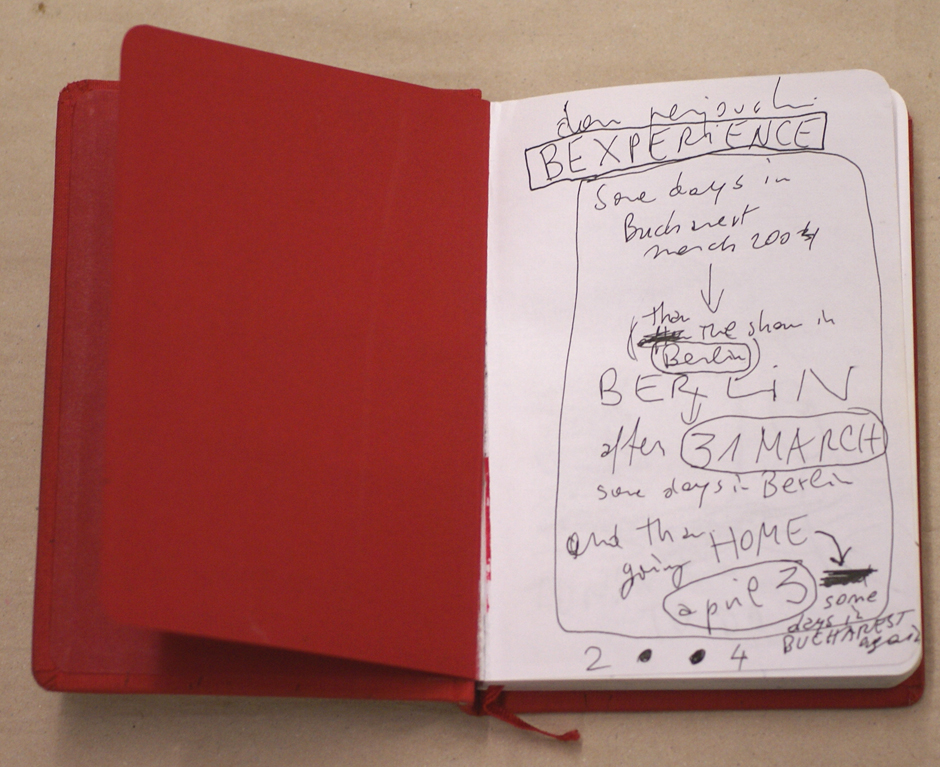

Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi has been intensely active in his country’s cultural life from his base in Bucharest since his work began to gain prominence in the late 1980s. In this 2012 interview, the cartoonist and publisher talks to Max Dax about the formation of his distinctive working method and what he continues to draw inspiration from as his practice widens.

Dan, you once said that three things impact your art: the political events of 1989, the free press, and the international art scene. How are these three different entities connected?

I was academically trained as if I were in a zoo—very detached from society, because everything that I’ve been studying had nothing to do with what’s going on beyond the school. The revolution changed this situation changed in my country. In 1990, I spent more time engaged in the protest on the street than indoors. That kind of reality modified the way I was looking at things, but my skills were not enough to correspond with this change so I tried to find a territory where I could get a hook in. I found it in the media.

You mean reality suddenly invaded your life?

These events shaped everything I knew about society and life. There were people dying, there were heroic moments, depressing moments, pathetic moments. At that time, the most interesting territory in my country was the new press, because for the first time in recent history, they could print what they actually thought. It was a boom of newspapers, people queuing for hours to buy something, so I moved into illustration—although I was trained as a painter.

The art galleries at the time were very boring compared to everything else that was going on in journalism, so I migrated to this journalistic territory. I started to illustrate texts that had something to do with my reality. Then I could travel, which is worth mentioning, as I was unable to get out of my country until the communist system collapsed. In our travels, my wife and I soon realized that Romania had been cut out of contemporary culture for decades. It’s hard to believe, but we were missing 50 years! The art of the ’50s, all the way through to the ’90s hit us at once. We didn’t have any basic knowledge; our education had barely reached Picasso. Of course, this all influenced what I was doing.

In addition to becoming an illustrator for the free press in Romania, you did your own newspaper, Dan Perjovschi Newspaper, in 1992.

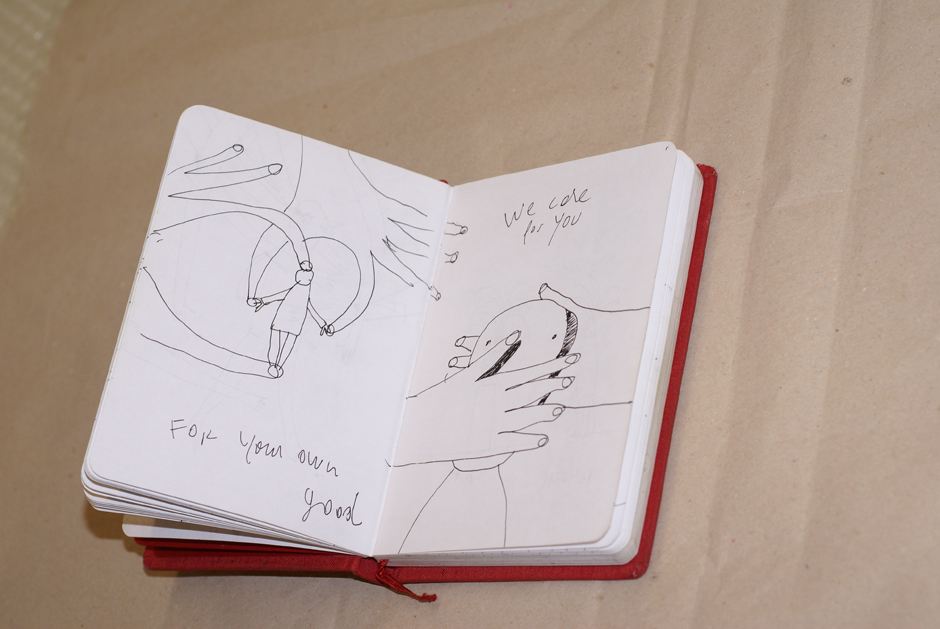

Everybody was very poor at that time—as was the art system. There was no money for catalogs. But I was working for a newspaper, so I knew the practices and could organize paper and a printing machine, and whatever help I needed. The first issue we printed instead of a catalog and it was cheap. Since then, it’s become a practice. Even now, I’m producing my what I call “eight page galleries,” a freely-distributed newspaper with my drawings. I like very much that I’m caught in the art market a bit, but still have this medium that can be distributed to exhibitions, that can make physical contact for free. I love the medium of newspaper; I love printed matter in general. My art is temporary, my wall drawings have a temporary appearance, and newspapers are also a temporary practice, because people often don’t keep them—they might throw them away tomorrow. Like a performance, newspaper is of-the-moment.

Like the Internet, which is even more immediate?

Although I’m actually very low-tech, I’m fascinated by technology. For me, it was not a conceptual decision; more like necessity, somehow adapting myself to the situation and finding a strategy. Only afterwards came the conceptualization: what kind of space is it, published space or not, free or priced. First I saw the possibility of doing something in a context and with no money. It was something that had to be managed somehow… we didn’t even have a Xerox machine! I just profited by the coincidence that I had migrated to journalism. In some respects the journal and the printed media were my second school somehow.

There’s a saying that ‘nothing is as old as yesterday’s newspaper’. But that’s only one side of the coin. We’ve all experienced the fascination of discovering a pile of newspapers. It’s like calibrating yourself, seeing what was happening a week, a month or a year ago. I worked with this weekly magazine called 22 in Bucharest in 1990, and every year they bound the yearly collection together. I have all the piles, and I’m showing it as a sculpture in an art exhibition right now.

You were talking about the revolution and how everything opened up, but what was it like before? You’ve said that “doing something in a frozen society like communism was in itself a radical act.” What did you do during communism?

Under Romanian communism, you were given an obligatory job for at least three years after you graduate. Sometimes, if you studied the arts, you could even get a job in the industry. I was lucky and got work at a museum in western Romania, in a city were lots of young artists lived. Until today, I think it was a mistake from the communist party. We would get together and organise exhibitions and every week we would do a show. Even the communist censors would say “oh, you’re doing a show” and they’d come and take a look. So in that sense the act of doing was radical because the rest of society was just waiting for the dictator to die, like they’re doing in Cuba today. I was born in 1961 and the dictator in the ’70s was more liberal, but where I was educated and grew up studying art our society was completely frozen. So doing these exhibitions was an answer.

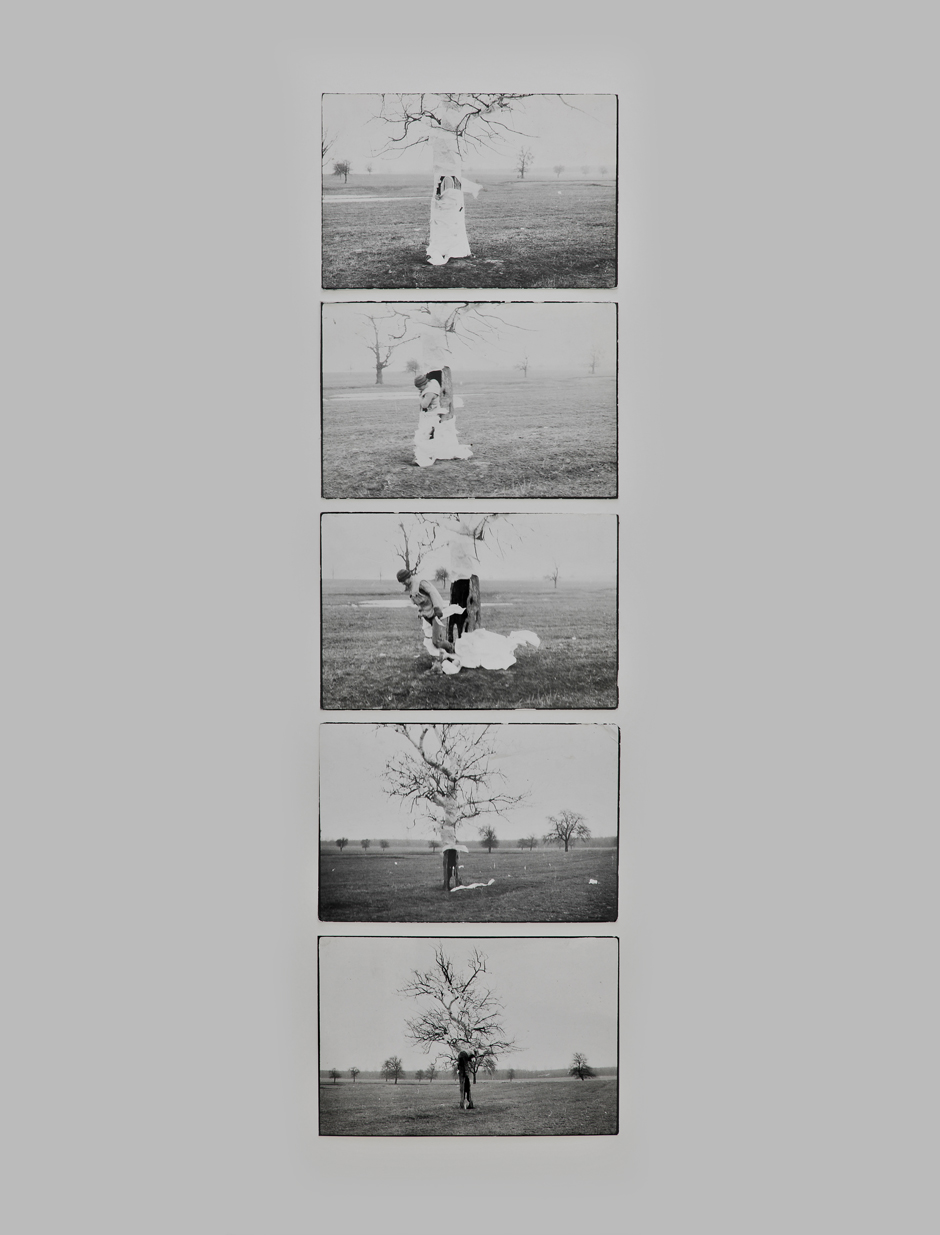

Our homes were the only refuge from censorship, so we’d use our apartments for artistic projects. These exhibitions and performances were very private—only the closest of our friends would come. My wife would do performances with no audience, myself being the only witness to document them with a camera. We couldn’t place it in our art history, but it was instinct. Later, of course, it turned out that it was great to have documented everything. But all these actions were merely ways to somehow survive with our mind intact.

Now you draw pictures that only exist for a limited time; is this an extension of what you did back then?

In some ways yes, but it also comes from practice. I was very poor, Romania was very poor, nobody would pay me transport or insurance for my art, and there was no system to support me as a professional artist. I had to invent a strategy to be free. You can carry some drawings in your suitcase but you cannot fill a big space, so I ended up drawing my art directly on the walls, just to minimize infrastructural needs. I started to reduce everything in order to unleash my freedom of movement. Now, I don’t have a plan, I free my mind… I cannot stand having a plan. My work is like a performance, and because these pieces have to be painted over, I have to digest the idea that I’m a temporary presence, an idea which has become a philosophy. At the beginning it hurts to see your art overpainted, but now I see the potential: every time a piece is painted over, I can dream of doing it better.

Dan Perjovschi’s work will be featured at the ACT exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope. Click here to read more interviews in the ACT series.

Published September 24, 2014. Words by Elissa Stolman.