Art Collection Telekom Presents: Sejla Kameric Discusses the Trauma of War

In anticipation of the Art Collection Telekom exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope, EB.net will roll out a series of seven short interviews with contemporary artists from Eastern Europe. They’ll all appear at the exhibit, which features a selection of works from Art Collection Telekom artists in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Fragile Sense of Hope opens at Berlin’s me Collectors Room/Stiftung Olbricht October 10 and ends November 23.

Our first subject is Bosnian artist Sejla Kameric, who hails from the formerly war-torn capital of Sarajevo. Known for her highly political works in various media, including film, and book design, Kameric’s focus is often the trauma leftover from the Siege of Sarajevo, the longest siege of any city in modern warfare, which began in 1992 when Bosnia declared independence from the former Yugoslavia and lasted until the end of the siege in 1996 (the war ended in 1995). During the blockade, some 14,000 people died, including more than 5,000 civilians. We spoke with her about the horrors she witnessed and how they informed her work.

Sejla, you were an eyewitness to the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s.

Yes, I was.

And you were sixteen years old then, right? I’d imagine that this dramatic and sad situation must have been formative, to say the least. Did it also influence your decision to become an artist?

This extreme situation changed everything—it was a very drastic change. Before the war, I was just a teenager going to the art high school who was interested in everything related to art. Then the siege of Sarajevo started, the country was in the midst of a war—it was a huge shock for everyone. I witnessed many tragic things, and that obviously completely changed who I was. It made me grow up very quickly.

Did you loose confidence in the world?

I did, absolutely. In hindsight, this was actually not a bad thing. I had to understand the hard way that justice is just a concept, and that it doesn’t necessarily apply to everyone. I had to learn that there is no greater power that can change things and can make things undone. I understood early on that life is a struggle and that survival is a mental game. I had to learn that I had to keep on going, keep on resisting and fighting and to do whatever I could to survive. These experiences were formative and influenced everything that was later to come in my life after the war—both personal and in terms of my artistic career. The war is reflected in my body of work, obviously.

Can you recall when you became a politically motivated artist?

Honestly, this wasn’t something that I consciously decided. For me, art is not a goal—rather, it’s a means of self-identification. The work that I am doing comes very naturally from the things I experience, from things I am feeling, and that concern me. All of my art is basically inspired by the things that I see or witness. My art rarely is an act of conscious decision or purely conceptual. I am also not a political artist in that sense.

I sincerely believe that art needs to be engaged; artists need to reflect the society around them. That’s not a choice for me. I can’t stay mute to the things that surround me. I need to comment on that, and I need to think about how to change the world. Of course, I don’t believe that it’s easy to change the world. But I do believe that the artists should at least try.

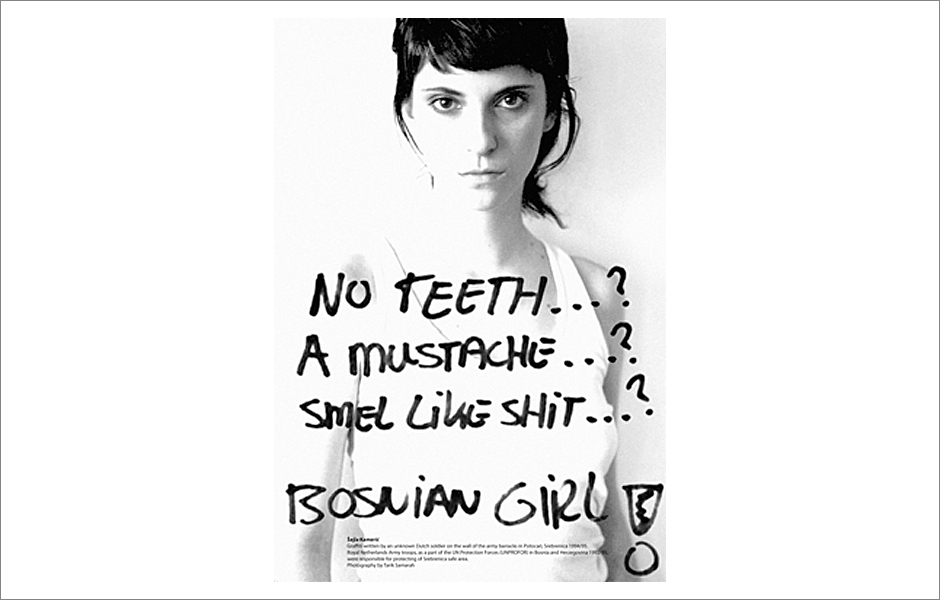

One of your key pieces, Bosnian Girl, is a self portrait, and there’s a line written over it that reads, “No teeth…? A moustache…? Smel like shit…? Bosnian Girl!” [sic] I understand that this insulting sentiment was written on a wall by Dutch UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) soldiers—not by the Serbians, who were attacking the city.

In 2003, my photographer friend Tarik Samarah was one of the first journalists who was allowed to visit the Factory in Potocari that was used as a UNPROFOR barracks near Srebrenica, another city that was under siege during the war. After the fall of Srebrenica, refugees came to seek shelter in the UN base. But, unfortunately, the UN soldiers were outnumbered and didn’t know how to handle the situation. They basically couldn’t even protect themselves, not to mention all the people who needed help. So, after the fall of the city, this factory and former UN base was used as a concentration camp. More than 8,300 Bosnian men and boys were executed by Serbian forces there—the massacre of Srebrenica.

When Tarik went there in 2003, he found and photographed a lot of evidence of what had happened there, among them graffiti done by the Dutch UN soldiers. Most of this offensive graffiti showed how unprepared and inadequate UN troops were. They were just young boys and probably very frightened themselves. Among those I found Bosnian Girl graffiti that used for my piece.

If there were a lot of examples of graffiti like this, why did you pick that particular one?

That one was particularly important to me because of the crimes committed against women during the war and prejudices that we were confronted during and after it. I basically had to write it on myself, I had to carry it along with me. By putting it directly on my image, I made sure it would be confrontational, especially in light of the massacres. And I wanted to shine a light on the third party in the conflict, the UN soldiers.

How do you see, in that context, the exhibition’s title “A Fragile Sense of Hope”? It’s taken from one of your pieces.

I am very happy that the show’s title comes from one of my works. I am most flattered by that, but I also thought that it’s a very precise description of how artists are dealing with the recent history in the Balkan and in Eastern Europe—with all the transitions and all the conflicts, all the dilemmas and all the identity questions. All our journeys were like a fragile sense of hope.

The poster and the catalogue of the exhibition both feature yet another work of yours. It’s called “Thirty Years After” and it’s also a self-portrait.

That one was done in 2006 and it’s one of these works that actually happened very fast. It basically says that sometimes you hide behind what you’ve earned, and that’s who you are. The picture shows me wearing white gloves and gold rings covering my face. Maybe one day, these gold rings will save my life—or my family’s. My mother exchanged her golden rings for food so that our family could survive in the recent war—my grandmother did the same in World War II. Of course, I hope that I’ll never get into a situation where I have to do the same, but in my subconscious, somewhere, there’s a deep need to secure myself, and maybe that’s why I’m covering my face.

In the light of your work “June Is June Everywhere,” that totally makes sense. It’s a photo of bullet holes on your parent’s house.

It’s a photo of the outside wall of my bedroom, exactly where my head rests while I sleep. It’s made out of hundreds of hand-printed black and white pictures with the same motif: a wall with bullet holes.

Would you consider that photo a self-portrait as well? I thought so.

Yes, this work is a self-portrait. It’s obvious that in my work, I come back to certain subjects and of course I am interested why that is. Why am I always coming back to the same topic? Why do artists repeat their means of expression? Our practice becomes our obsession. In my case, I locate this in the image of the scars on the wall from the bullet holes. I survived it, but the scars are there and they are visible, they are obvious—they make me who I am.

You survived the siege of Sarajevo, but friends of yours didn’t. I know from many survivors that they feel guilty. They wonder why they survived and not their loved ones. Do you ask yourself similar questions?

It all comes back to the general question of individual responsibility and being proactive in the society in which you live, to make a change. As an artist, you have a power to be more than yourself. Why me and not someone else? I think we should always ask ourselves this question regarding our situation and our destiny.

Published September 10, 2014. Words by Max Dax.