The Costs of Paying Artists

On April 19, 2015, the PollerWiesen Open Air festival in Cologne made history.

For the first time, Germany’s royalty collection society and performance rights organization (PRO), GEMA (Gesellschaft für musikalische Aufführungs- und mechanische Vervielfältigungsrechte), accepted records of the tracks played during the DJs’ sets. The playlists were compiled and submitted by a startup called Geo Track ID (GTI) and made PollerWiesen the first festival in the country to compensate virtually every artist whose music soundtracked the event. It was a significant victory for the young company, which installs hardware in club and festival sound systems that identifies and logs the songs played in order to distribute royalties to the copyright holders.

“We’ve had umpteen conversations with GEMA, and at this point, they said, ‘OK, we’ll have a look at your system and we’ll try to integrate it with our existing club monitoring,’” says GTI founder Gavin Burke. “The way it’s set up at the moment is that, after a DJ finishes their set at a festival, they’re meant to write down all the tracks they’ve just played. Now we just put the box in, it generates the playlist, and then we send those in to GEMA through the promoter.”

Burke’s black box offers a solution to controversial aspects of the “simplified” tariff reforms GEMA proposed in 2012, which threatened to put underground nightclubs in Berlin out of business with unaffordable fee increases. And because the royalties collected from nightclubs are distributed to rights holders according to sales and radio airplay, that money goes to high-revenue mainstream artists rather than those whose music is actually played at these small venues. According to a press release from the Association For Electronic Music, an advocacy and lobbying body whose supporters include Nile Rodgers and Richie Hawtin, European collections societies deliver about £100 million in performance royalties to the wrong hands.

Geo Track ID launched in 2012 following a wave of demonstrations against the planned reforms, which calculated how much clubs owed based on the size of the venue and the price of entry. Because the new scheme assumed that the clubs were completely packed from open to close and charged huge increases for long events, its implementation would have resulted in astronomical fee escalations. In response to a summer of protests that greeted the prospective alterations, GEMA agreed to delay the amendments, and once the risk of losing Berlin’s most famous clubs was mitigated the issue pretty much disappeared from the press.

Meanwhile, GEMA applied a 5 percent increase in its fees across the board, then another 10 percent in April 2013, and at the end of 2013 the association of publishers announced that long-term increases for clubs would reach 29 to 64 percent. It also adapted to mounting concerns about European copyright organizations’ anti-competitive behavior, as European PROs hold monopolies in their constituent territories and draw out the process of licensing in the EU by demanding that companies deal with each country individually. In 2013, Europe’s General Court upheld a 2008 ruling by the European Commission that demanded the collections societies allow songwriters to choose one agency to handle their licensing across EU territories, and last month, GEMA teamed up with its counterparts in the UK (PRS) and Sweden (STIM) to form a pan-European body called the International Copyright Enterprise.

Thankfully, people like GTI founder Gavin Burke have been hard at work on alternatives and improvements to the existing system, the first of which debuted at PollerWiesen. Rather than referring to the pop charts to determine who should receive the licensing fees collected from a venue or festival, Burke’s black box identifies tracks in a DJ set using the database compiled by Juno, “the world’s largest online dance music & studio equipment store.” The site covers famous and little-known artists alike, but so far GEMA has only accepted Geo Track ID’s playlists for tracking festivals. It hired a French company, Yacast, to handle nightclub licensing and distribution.

“Again, though, it’s aimed at pop music,” Burke says. “They don’t have any proper underground music that would be played at the clubs under threat from the GEMA tariff increases. They don’t have Berghain techno in the Yacast database.”

Burke’s goal over the past three years has been to change the way GEMA determines how it distributes the money it collects by introducing technology that identifies “proper underground dance music.” “We’re discussing with them about how that calculation would actually change, and how that would occur,” he says. “[GEMA’s] working on it.”

While GTI and Yacast work within GEMA’s existing system to improve it, other companies have more aggressive plans. Kobalt, a British rights management and publishing agency founded in 2000, tracks and collects royalties directly from platforms like iTunes and Spotify for the 6,000 artists, songwriters and publishers it represents. It registers its clients with collections societies like GEMA, as payments are only sent to artists who are members—so if a black box identifies a track by an artist who isn’t a GEMA member, that artist won’t receive a royalty payment—and guarantees that their songs are fingerprintable and thus recognizable to tracking technology.

According to Kobalt’s website, its “pioneering collection technology platform bypasses the middleman and collects directly” from societies and platforms that generate licensing revenue, which means that its role not only bypasses but replaces many of GEMA’s functions. And while GEMA and other societies only operate within their specific countries, Kobalt offers global royalty services. In February, the firm received $60 million in funding from Google.

“Kobalt is coming like a juggernaut at the whole industry and are vocal in their aims to disrupt the status quo. They’re openly critical of the current PRO system,” Burke says. “We, on the other hand, view the PROs as a necessary part of the bigger picture in making sure that artists get paid correctly. The core idea is not a bad one—there just needs to be more transparency and fairness in how they operate.”

Burke’s eagerness to cooperate with GEMA, not stage a coup, has probably played a significant role in getting GEMA to respond to his emails and accept his efforts to alter the system. It’s an opportune moment to enact change, as the post-protest period has proved crucial in transforming the society’s unpopular image and determining its future. GEMA has long frustrated artists with policies about sampling and distribution that many perceive as antiquated bureaucratic interferences with creative processes. Burke says that now the society understands that they need to alter their system, and he’s willing to help them do it.

“GEMA and other PROs are under pressure from external EU directives to be more transparent in what they’re doing, to create transparent databases so everybody can see what is happening,” Burke explains. “I feel that GEMA’s starting to understand that they need to change, and one way for that to happen is for them to accept the fact that dance music is a big cultural element in Germany, and to engage with it rather than ignore it. Another step is engaging with us, which they’ve already done.”

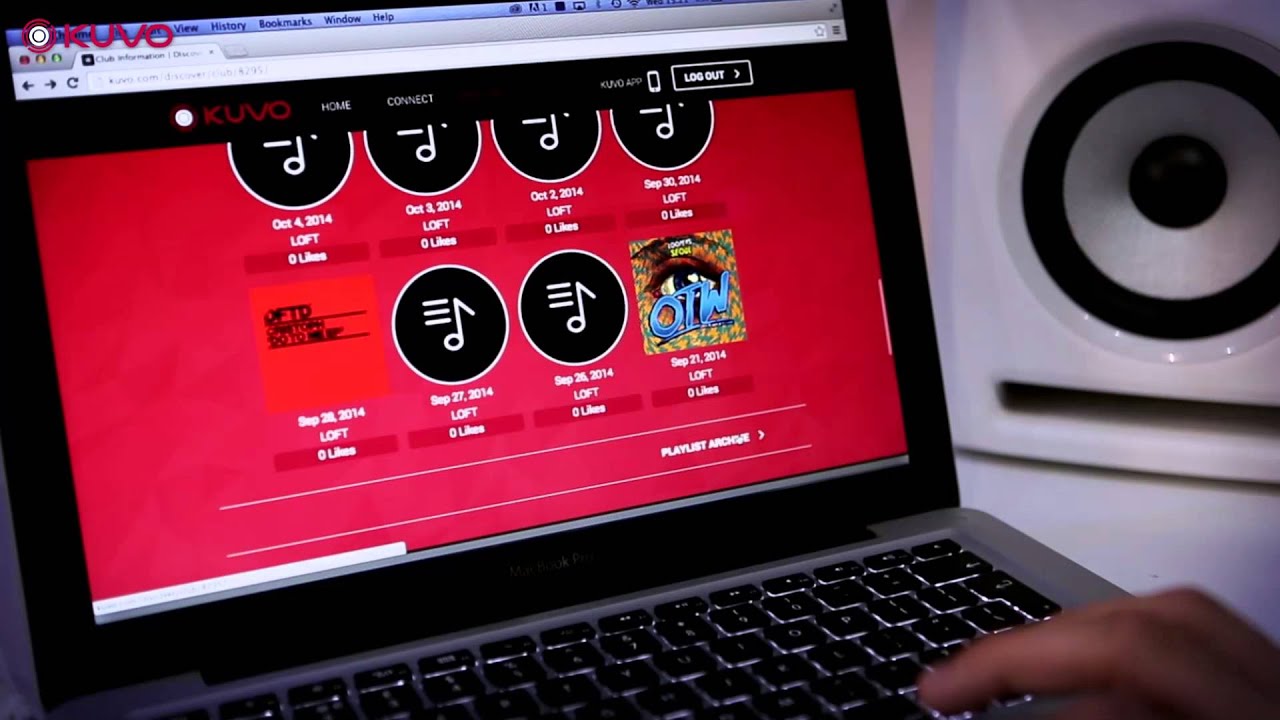

The challenge now is finding a way to make the company profitable. So far, Burke has funded the project with a small investment from Juno and with the help of his other software company, Future Audio Workshop. One of GTI’s main competitors, the Kuvo system that was developed by the DJ equipment manufacturer Pioneer, earns a profit by combining the black box model with a social media aspect. Kuvo reads the metadata on an MP3 or CD to identify a track, then uploads the playlist to a cloud server and a public profile. Its privacy policy states that it collects users’ information to share it “with third party partners such as analytics and advertising partners to provide services such as analytics and online advertising.”

“Recently, looking to advertising as a revenue generator for the music industry seems to be a big trend,” says Burke. “I’m not 100 percent sure that corporate sponsorship of art should be the only way forward, though, because it nullifies a lot of the aspects that make art interesting. Independence needs to be an option if we’re to keep music a vibrant and challenging art form, and that means alternative revenue streams to advertising need to exist.”

Burke’s conviction is clear and his point is pertinent: marketing is a problematic means for supporting and enabling art. But his solution to flaws and challenges in artistic industries—surveillance technology—also raises concerns. It undermines much of what can make clubbing powerful and liberating, like the premise that a nightclub is an temporary autonomous zone that provides a brief escape from the outside world, where everything is mapped out, audited and Googleable. And the idea that the clubbing experience isn’t subject to life’s rigorous scrutiny and empirical laws is part of the fun.

Track identification software is part of a larger impulse in contemporary culture to use technology to monitor and exploit personal movements and data for unspecified purposes. Although Burke’s goals can be perceived as virtuous, it’s risky to count on the arbiters of technology and industry to have good intentions or to use the data they glean responsibly. The advancements that allow GTI’s black box to accurately name songs in a DJ set are part and parcel with those that Facebook and Google are developing to recognize people based on childhood photos. Before Yacast took charge of identifying tracks played in underground German nightclubs, it partnered with the company LTU, which pioneered image recognition technology and became the most deployed software of its kind. LTU’s other clients include the U.S. customs office, the FBI and the French and Italian police. The endeavor to fairly compensate artists for their work is worthwhile, but the means to that end also have costs.

Cover photo via bz-Berlin.

Published July 24, 2015.