The Techfather: An interview with Juan Atkins

Let’s start with the facts. Juan Atkins is the Techfather. He is the father of the Holy Trinity of Belleville. Top king of the three wise men of techno. Kraftwerk may be the robots but Juan Atkins is the mo’bot, taking it to the dancefloor while simultaneously achieving an atmosphere that never fails to draw in deep. The new set of remixes of his tune “OFI” on Apollo Records was possibly my favorite release of 2012. This was followed by a new Model 500 release, “Control”/“The Messenger” on R&S, a classic yet refreshed workout. Hence it was with 14 year-old pubescent girl giggling excitement that I went to meet the innovator in Berlin.

Before we get into detail, what is coming next from Model 500, what’s new?

Juan Atkins: I’m always doing something new. Right now I’m preparing a Metroplex release. It’s not a Model 500 release; it is collaboration between Mark Ernestus and me. The name of the track is called “Dark Side”. We’ve got a Ricardo Villalobos mix on it and more. It’s funny because we don’t even have a name. Him and me just went into the studio and just did this thing, and we don’t yet know what we want to call this project. That’s going to be Metroplex 040.

What about a Model 500 album?

I’m working on a model 500 Album. For years I go back and I always say, “The album is gonna be done on this day or that day,” and I never make the deadlines. It’s one of those things where you have to feel it. You’ll know when.

Because my own release is so overdue, I tend to put myself under pressure. I get up in the morning and I’m feeling guilty already. I’ll be on my first coffee and I’ll think, “I should be doing this, I should be doing that,” but if I don’t have the motivation… Maybe you’re more in touch with when it feels right.

JA: With me it’s the exact same thing. I’m at that point now where I’m waking up and I’ll be getting e-mails asking when it’s going to be done. “We’ve got distribution, promotion, blah, blah,” and “What’s the plan, man?” [laughs]

Do you work in your home studio?

I work at home; I’ve also done some recording with a Belgian guy in his studio where he has all this analog gear and we mix it with all the latest technology. It’s a really great studio.

What’s his name?

His name is Gregory [Lacour]. He used to run Elypsia Records, and one of the big distribution companies in Belgium. I went and did one track with him. It’s cool.

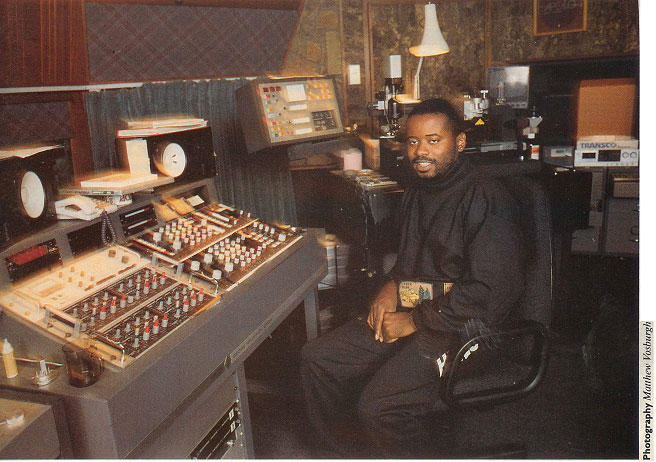

I saw an old photo of you from an interview from Music Technology Magazine from 1988. It was you in a serious ’80s outfit and you were sitting in front of what looks like all this vintage mastering gear. Machines! [Laughs] It looked fantastic! And you were talking about how at that time you had not yet started using computers, when some others had already been doing so. You were still doing it your way. Others were using Atari etc, and you started shortly after that.

Actually, the early software-based sequencers were just a nightmare. It’s funny you mention Atari; that was when they were using the big floppy discs, the real five-inch floppy disc. You used to put them into the computer and they were really floppy. Do you remember those?

I’m not sure. I might have seen the next generation of Ataris then. They weren’t bad, actually. We used to program stuff on those and then record it all onto tape. That’s how you got that amazing tape sound still.

Ultimately we would do that too, if we would even get to that stage. It was so tedious. I mean, if you weren’t constantly saving—you couldn’t just save it onto the computer, you had to save it onto those floppy discs. And if you didn’t save every three minutes… These computers were famous for locking up and you would have to reboot, and of course once you do that everything is lost [laughs]

I can remember one time I was getting to the end of a track. I was finished, and the computer crashed. [laughs] And I lost the complete track. And it was so funny because the software was such, you would have to write the pattern the whole way to the end, because if you looped, there would be a hesitation in your boot. It wouldn’t loop directly back and then go back to the top. It was horrible.

“OFI”, the release of the end of last year was in my chart of best releases of the year. Who decided to get some mixes done and who chose the remixers?

It was R&S.

Did you know those people that they chose?

JA: Not really.

Those mixes are incredible. What was your reaction when you heard them?

When I heard them and they sent them to me I was like, “This is great.” Those mixes are really cool.

By loading the content from Soundcloud, you agree to Soundcloud's privacy policy.

Learn more

I seriously think as a package, this might be the best set of mixes I’ve ever heard in my life and I just wanted to know who chose them. There’s a Shadow Child & Horx mix. Blows your mind, right? And there’s a Sei A Mix, which is another dimension. I was waiting for the bad mix, which never came. And there’s a Colonel Red ‘Drunken Masta’ remix. Was your reaction like, “Yep, this is doing me justice.”

Yes. I heard them back-to-back, and I just had to hear the first few bars of each one, they were so good. R&S just went ahead and did it, and before they did anything with it they sent it to me for approval, of course. I approved just about all of them. There might have been just one mix that I didn’t care for.

How do you decide whether anything you release is a Model 500 release or one of your other monikers?

Just based on the track. I usually know before I start a track what it’s going to be for. Usually I reserve Infiniti for the real underground purist crowd. The straight, head, techno expectations.

The Tresor crowd.

JA: Yes, the harder basement style stuff. That’s usually under Infiniti, whereas the Model 500 stuff tends to be more song-oriented. Or if I do stuff with lyrics and vocals, that would be Model 500 stuff.

You mean the spoken ones? You do those yourself?

Yes, but on that Mind and Body album I had a couple of different singers. Actually on that next album I’ve got a track that I did with my daughter. She’s actually singing on one of the tracks.

Now, Cybotron—do you actually realize how ahead of its time that was? I’m listening to it now and my ears are growing. People are trying to do that now and it also sounds in places like what Cabaret Voltaire were doing. A bit of Sugarhill Gang maybe there as an influence. And it has those fabulous vocals.

Thanks. I think I’ve just recently come to that realization myself.

It’s what everyone else ended up doing. That stuff is so incredible. Who did the vocals on the Cybotron stuff?

Depends on what track. Rik Davis would have done any of the singing stuff, probably.

Were you influenced by any other European synth pop groups, like Eurythmics, Depeche Mode, etc? There are a couple of tracks that sound like you were totally aware of that sound also.

I definitely had some influences. At that time, when I started recording, the groups that were around were of course Kraftwerk, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Human League; not so much Eurythmics. “Sweet Dreams” was a big hit, but I was maybe on my third release at that time. But definitely Human League and Depeche Mode.

I read that you left the project because it was going too much into a pop direction for you, but then I read somewhere else that it was because it was getting too rock ‘n’ roll. I didn’t know what the real reason was.

More rock ’n’ roll. By the time we were on our third or fourth release, before the album came, we started adding guitars and [guitarist John Housley] was a real Eddie Van Halen type.

And now all of that is hip again. They’re doing the mad guitar keyboards again to get that ’80s sound.

Really? I have to keep that in mind because I’ve just been propositioned by a guy from a very famous rock band (I’m not going to say who now), and he’s into doing publishing. He helps a lot of guys in Chicago with publishing and stuff and it blew me away, as he was in this hugely famous group and what he wants to do is play a guitar riff on one of my tracks.

So, it wasn’t the fact that there were vocals that were putting you off, it was the guitar solos?

It wasn’t even just the guitar solos, but he used what you would call electronic guitars, meaning that he had an actual guitar synthesizer. The guitar is just the controller and it controls the actual synth. He did that on a couple of tracks and you could tell that in his heart that he was a real rock guy. There were a couple of tracks like “Enter” and “The Mind” where he played a straight-forward guitar and it was cool, I loved it. But then he wanted to go even more in that direction and I’m like, “Man, you can’t come behind a record like “Clear” and do that.” How can you come behind a record like “Clear” with a rock ’n’ roll record? The record company was asking for the next single and they handed in these guitar tracks, and even the record company said, “No, we don’t wanna do this.” [laughs]

Well, this was destiny then, that you went where you needed to go.

Yes, that forced me to start Metroplex and that gave the cue to all my friends, to the whole Detroit techno generation, and I guess, had I not done that, none of that would have happened.

How do you come up with a Model 500 song title? All your titles are very defined. Do you sit down and decide that you might want to write a song about Detroit or something?

No, more often than not I don’t know what is going to happen. Sometimes I might have an idea but I never ever usually have an idea about the title. Usually that doesn’t come until the very end.

But you kind of know what you want to sit down and develop in terms of sound?

Rarely do I know. There’s only been a few instances where I went at it knowing I wanted to start with a certain kind of beat, or bassline that I had in my head, and I finally get to put it out. But by the time I finish the track it’s usually never what it was when I started.

But now, with Detroit going through these massive changes, is the new Model 500 album going to be shaped by all these fresh influences, because of all the visual and social changes in Detroit now? Are you out there looking around, getting inspired and then writing all those tunes that are influenced by Detroit as it is now?

Not really. It’s funny; I don’t pay too much attention of what’s happening in Detroit.

How can you not when everything on the one hand is falling apart, but out of that new things are growing, like social changes? Maybe because it’s outside your door you’re not going around seeing it that much? But it must influence you in some way. I mean, the crumbling empty buildings and people moving into the empty suburban houses…

It’s not something I pay too much attention to, because, I mean, I was born and raised in Detroit, so I’m kind of oblivious.

But it wasn’t falling apart then in that way, when you started.

Detroit has always been falling apart. [laughs] The only time I can remember that Detroit was really vibrant, and downtown was crowded with people shopping at all the department stores, was when I was a kid. Before I even thought about making music.

I bought a lot of books about Detroit, with all the famous concert halls, cinemas, opera houses, etc in ruins and poor people taking the iron structures out of them to sell the iron for money. And I actually am thinking about going to Detroit and shooting a documentary about it. I know I’m not the first person to do this.

Actually those are the kinds of things that you kind of want to escape from.

But it must give you some kind of new ideas? Also, what I learned is that young people are moving into all those empty suburban houses. Sadly, these are the houses that people lost through the banks giving them expensive loans, which they were unable to repay. And young people are moving in and growing their own food. Mini-farms are being established; so out of the destruction comes some new social movement. People are doing something positive. I know what I would do. I would sit down and write about all of this.

Naaah.

That’s funny! You don’t work that way?

I’m sure that subconsciously it affects what I do, but somehow I am more into creating an alternative to the reality, as opposed to perpetuating.

I’m accused of writing miserable songs. [JA laughs] Larry Flick from Billboard Magazine interviewed me live on the air and his first words were, “So Billie, why are your songs so miserable?” I think I would quite happily be sitting in Detroit and writing about doom and destruction. But I also write from a perspective of what comes out of that. So, I don’t think my songs are miserable at all, but the press calls me “The Nico of the rave generation.” I guess my songs are reflective. I would probably love being in Detroit for a month or more. It’s very interesting to me that you don’t necessarily come from that perspective, because certainly your early Model 500 songs are influenced by Detroit, but I guess it comes from a more individual place then.

Yeah.

So, would I have to hurry up if I wanted to come and make a documentary, because all the buildings are physically collapsing now, because of the iron structures being taken by looters?

Actually, yes. Every time I ride down Woodward I see a new space where they’ve cleared the area. They are starting to get rid of those ancient buildings.

I’d like to get some spontaneous answers from you about the influences about some of your classic songs. The first one would be “Nightdrive Through Babylon”. Your stuff always seems to take that Kraftwerk influence and take it somewhere else. One could say while they’re resting on their laurels, your stuff takes it further. Is this track inspired by driving through Detroit?

Yeah, that track is one of those that actually go with what you were saying in your previous question. That would be one that probably draws on the grimness of Detroit. But there is also the biblical reference.

Actually this was meant to be a Cybotron song. What happened was when we split I was like, “I’ll have that.” [laughs] Because of the rhythm of the track, to me that was more of a follow-up to “Clear”. If you listen to it, it is more like “Clear”, as it was sort of the template for that song. Even though a lot of that old stuff we called a collaboration, I was more responsible for the tracks like “Clear” and “Cosmic Cars” and those sounds, whereas Rik would maybe play a riff on it or do a little keyboard line or vocal riff and he would get 50% of that song. When it got to the point where we were getting ready to split, I was like, “You’re not getting 50% of this one.” [laughs] Although that’s him talking on this particular one, that’s Rik actually. But I just had to have it, because I was in love with it. When I first made it, it was one of those ones where I felt, “Oh my god,” so I put it on Metroplex.

And just to get back to your question: a lot of stuff that I wrote with Rik not only has social and political content, some of it had the biblical references as well. So, there’s the Babylon reference and “R9” was a reference to Revelation 9.

Were you influenced by The Sugarhill Gang and Grandmaster Flash and people like that?

I was in my senior year in high school when “Rapper’s Delight” came out. So, we were listening to that stuff.

Sugarhill Gang had the beats that now everyone is influenced by.

Yeah, like “Scorpio”.

They had some serious beats going on that everyone now copies.

Now that I think about it, I think it might have slightly influenced me.

Yes, I can hear that on some of the Cybotron stuff. They had heavy beats, and also what they did was that they would put reverb over the whole track in the mix. I was in the studio recording a demo of what was supposed to sound like a Sugarhill Gang track and it sounded too clean. I asked the engineer, Steve Honest from Rock of London studios, why the hell it wasn’t sounding like the Sugarhill Gang track that I had brought in for reference. And he told me that they put this big reverb over the whole recording at the end of it. He knew what reverb it was and he put it on the track, and it did sound like one of those old tracks. I noticed that on one or two of the Cybotron tunes there is that reverb, definitely over the drums.

Yes it’s on the drums. A lot of that ’80s stuff sounds the way it does because, when all the digital reverbs came along, everyone went crazy. They were putting reverb on stuff that they shouldn’t have put reverb on. [laughs]

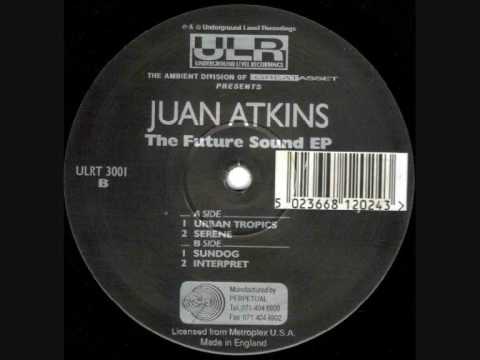

That’s why that stuff sounds so good! It has a kind of live feel. The other song I wanted to know about is “Urban Tropics”. It reminds me of the Detroit equivalent of the classic tune by Richie Rich, “Salsa House”. “Urban Tropics” captures a mood not many tunes capture, so I was wondering.

Actually, it was, I believe, Mike Huckaby, that I did this with. So, that was more his influence.

When I announced on my Facebook fan page that I was about to interview you, one of my fans told me to ask about the song “Techno Music”. How did the tune start and so forth?

I was living in California for a while. I moved there in ’88, and then I got a call from Derrick May and he said, “You gotta come back to Detroit. Record Mirror is here. NME is here. All the British magazines are here to do interviews and you’re not here.” [laughs] So, I drove back. The first techno compilation was coming together on Ten Records, which was Virgin. And we were being discovered.

I guess someone got the idea of doing this compilation. And the working title of that compilation was The House Sound of Detroit. And what happened was that we needed a track for this compilation, and afterwards they told me what the name of the compilation would be. And I was like, “Man, I’m not having that,” [laughs] and I called this track “Techno Music” and submitted it. Everybody at that time was saying, “If it wasn’t for Juan, I wouldn’t be doing this music,” and I had submitted a track called “Techno Music”, so they changed the name.

I also called you the Techfather in one of my tweets. So, from what I gather, Frankie Knuckles would be the Jackfather. Because from what I know, Derrick sold Frankie an 808, and thus Chicago house music was born.

You would never get anybody from Chicago to admit that probably Detroit kick-started their movement as well.

Well, I’m not surprised that they wouldn’t want to give the credit away, because in America no one gets their just credit for anything, no matter what they’ve innovated, so you have to cling on to what credit you’ve managed to create for yourself, I guess.

Everybody is a DJ who’s also a techno artist now. That’s the situation by default. You don’t usually produce music; you’re a DJ first. But by me being a DJ and a musician—at the time the two were separate. It wasn’t what it is now. Either you made music or you were a DJ.

I had this idea to combine the two worlds. First of all the TR-808 was brand new, nobody knew it. We must have had one of the first 808 machines. We were battling with this other rival DJ group and I said, “We’re gonna bring the secret weapon,” which was this drum machine, and you could basically make up your own rhythms. At the time, the rhythm tracks phenomenon, or shall we say fad, was happening, with one record label selling four albums of only rhythm tracks. So, I felt we could make up our own rhythms on the spot and people would go crazy. And sure ‘nuff, we took the 808 and had a couple of patterns programmed in and mixed them in just like records. You had a pitch control on it and you could mix it in just like records.

The beauty of that was, nobody else had whatever patterns you had programmed in there. They were your grooves, worldwide. That gave you an exclusivity, that gave you an edge. And then the fact that you could change the patterns right there, on the fly… man. And so what happened was, and it was funny, at the time everybody had a couple of machines from various deals or whatever, and this was only happening in Detroit—nowhere else I know of—and Derrick was short on his rent one month and said, “Hey, man, I gotta sell one of these drum machines because I gotta pay my rent”. So, I said, “Well, don’t sell it to somebody else in Detroit, because they’re gonna take it and use it against us!” [laughs] His parents had moved to Chicago, so he was back and forth between Detroit and Chicago. I told him to go and sell this stuff in Chicago, because if you sell it to someone in Detroit they’re gonna show up at the party and be battling us with our own damn drum machine! [laughs] So, he took it to Chicago and sold it to Frankie Knuckles. [laughs]

So, Frankie started doing the same thing in a club called The Warehouse. At the time it was a club in Chicago that was very, very famous. He started mixing in patterns into his set, and then I think he had a couple of partners, like Chip E and people like that, that actually took that drum machine home after their club nights, and started making beats and stuff. And so what happened was, he took it home and made tracks like “Like This” and “Jack the House” and would bring acetates back to the club.

My final question: Karl Bartos from Kraftwerk once said to me that he would be open to collaborating with me but that he could not imagine Aretha Franklin singing over a Kraftwerk track. I replied that she had happily done so for the last 20 years. My question to you is: will you record a track with me?

Yeah, I’m sure we can work something out.~

Title image of Juan Atkins by Luci Lux.

Published February 18, 2013. Words by Billie Ray Martin.