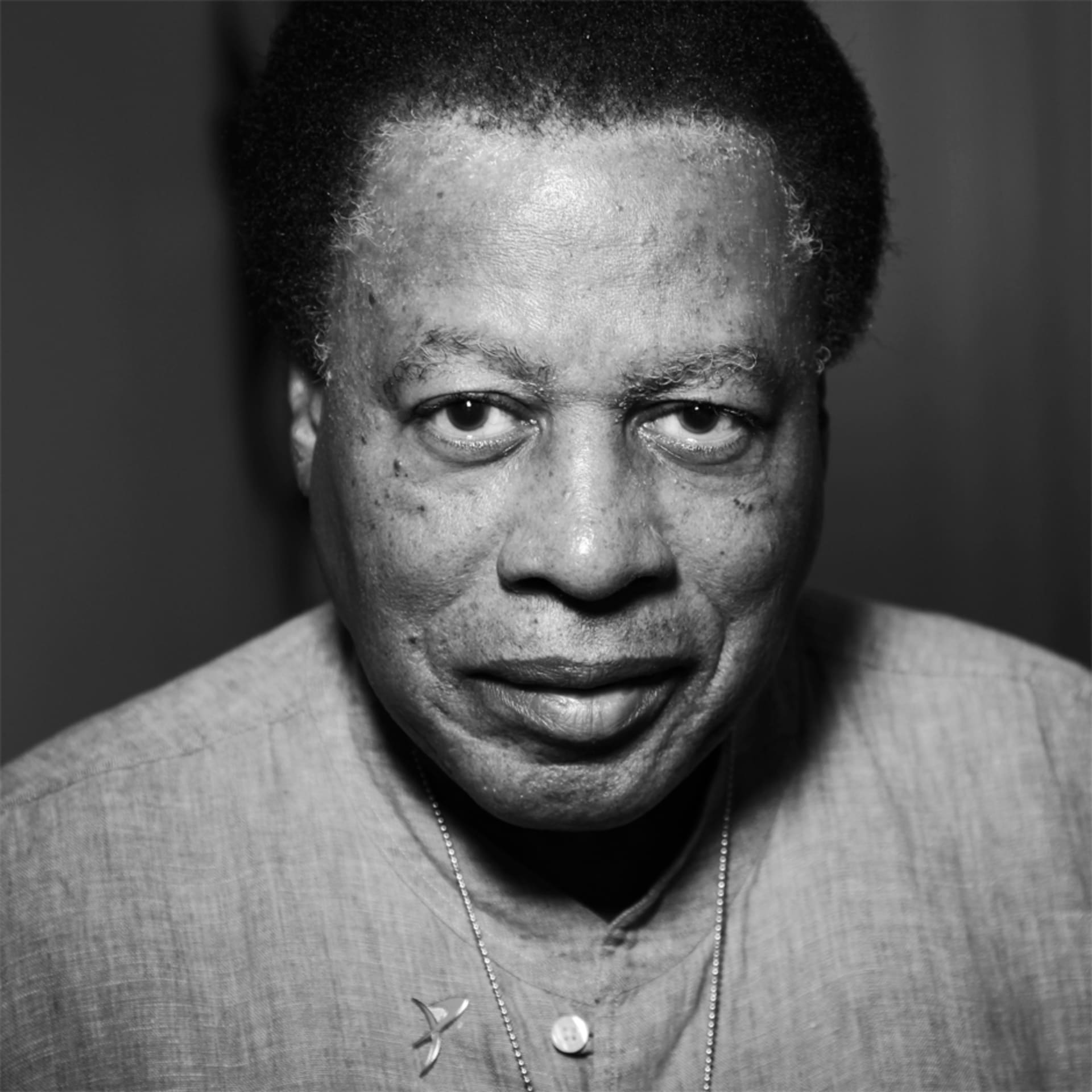

“To me jazz means: I dare you” – Max Dax talks to Wayne Shorter

Above: Wayne Shorter photographed at home in West Hollywood by Luci Lux.

In this interview, taken from the forthcoming issue of Electronic Beats Magazine (available June 1st), EB editor-in-chief Max Dax headed to LA to talk to legendary jazz musician Wayne Shorter. The Wayne Shorter Quartet is headlining Electronic Beats Presents at Jazzfest Bonn this Sunday. You can stream it here on ElectronicBeats.net.

Saxophonist Wayne Shorter is one of the last living jazz giants that defined the genre in its formative decades. Having started his professional career in 1959 with legendary drummer Art Blakey, Shorter joined Miles Davis in 1964 and in the late sixties helped usher in Davis’s electric revolution—a foundation he later built upon with the Weather Report. A practicing Buddhist, Shorter currently leads his own revered quartet. In Los Angeles, he discussed with Max Dax the psychology of risk-taking and the malleability of time.

Only recently, volume two of the Miles Davis The Bootleg Series was released by Columbia Legacy. It features stunning live material by the 1969 quintet, only moments before you guys went electric. Everything sounds unbelievably fresh even though it was recorded forty-five years ago.

Why would you say that was the case?

I think it’s because the sound of the 1969 outfit was never copied simply because nobody knew about it. There existed no official recordings of that band until now. How does the release connect the pre- and post-electric eras for you?

Well, hearing it again, it triggered a lot of memories. The recordings are from the Antibes Jazz Festival in Juan-Les-Pins. Only Miles and me had survived the previous line-up: Jack DeJohnette had replaced Tony Williams on drums, Chick Corea and Dave Holland had substituted Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter on piano and bass. Man, this was some kind of a tight outfit. But I’ll tell you what I connect with this particular recording: I was home in New York, finished taking a shower and the phone rang. It was Jack Whittemore on the other end of the line who was calling for Miles—he was his agent. We had just finished playing some place that week in New York. So Jack said: “Tonight we’re going to France.” We’d go there for one night and then come back the next day.

I guess that’s what you’d call short notice.

Actually, it wasn’t all that unusual. But in this case the rush led to the recordings that you can hear on the Bootleg Series album. Everything just happened so fast in those days. Everything changed at such a fast pace that if you didn’t release something immediately it’d be lost forever. I mean, one day later we came back from Antibes and played at Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey and I don’t think that we sounded the same at all.

You went through a kind of time travel hearing these recordings again and that’s what I’m interested in. Having been one of the creators of this sound, were you aware of the fact that you were working on a new direction in jazz back then?

Yeah. And I think that it is a great thing to finally share that vision with the people of today, even if it took forty-five years to officially surface. I still believe in a future jazz music. I am not trading in nostalgia.

With your own Wayne Shorter Quartet you recently released the live recording Without a Net. Once again you sound like you’re leaving a comfort zone, deconstructing scales and harmonies—like on the epic track “Pegasus” that you recorded in L.A. at the Walt Disney Concert Hall together with The Imani Winds.

In February 2013 I went back to New York to perform together with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. It was another version of “Pegasus.” There was a piece called “Lotus” and another one called “Prometheus Unbound.” I’m working on them right now. I’m mixing the music and all that. It will be released with a graphic science fiction novel. Don Was, who is now the president of Blue Note Records, wants to do it as a coffee table book. I forgot the name of the artist, but I remember that he’s from Atlanta, Georgia. He’s working on it right now in Switzerland because his wife is Swiss. I met him once in a hotel in London, and Don showed me some of his work. I especially liked one picture of his.

Can you describe it?

As I said it was science fiction, which I love. It showed some sort of a galactic council making judgements about which solar system is naughty and which one’s nice. He also did another book of all the racial cultures, pictures of peoples faces with a clock over their heads showing the time zones they’re in.

How do you think about time? I know you converted to Nichiren Buddhism. Buddhism says you have to live in the present tense, but as a musician you are actually obliged to be a man of the future. How do you deal with that dichotomy?

That’s the challenge of being in the moment. It’s a challenge to be in the moment where you don’t present yourself with your Sunday suit on. Actually I think being in the moment transcends time, because one moment is equal to eternity. In that very sense I like it when Stephen Hawking says that “nothing is wasted.” For me, nothing is thrown away, and there is no such thing as nothing. So I’m in all those, you dig it? I’m trying to live out the ongoing evolution of the word itself, the words that we say as well as the things that we think, say and do. Everything, including music, becomes a frontier when you try to do and to infer in the form of film, sound, literature or architecture. Everything we face becomes a precipice. The challenge for the masses is to turn in their medicine, to take responsibility, to prepare as well as they can and to then leave the world of followers. When they then stand at the precipice of the unknown, they negotiate this frontier as leaders. Individuals becoming leaders, individuals who experience singularity as an epiphany. Having said that we try to play music like this. Playing music should be a struggle, like going through resistance. It’s like how an airplane needs the resistance of the air to rise.

So would you say you accept everything as it results from your vision?

I surely don’t blame record companies or other people for anything. As I said, I accept barriers as the resistance that I need to fly. It’s my duty to find out what other uses there are for things that seem immovable. Every obstacle is a potential enabler. I don’t like the phrase, “Use the brains that the maker gave you.” I believe more in exploring the hidden potential of the brain. That’s why I’m trying to play music that actually recalls a conversation that I once had with Coltrane. One time he said that he’d like to make a record that he described like this: “You put it on, and it’s already there. It’s like you’re walking down the street and you see a door and you open it, and everything is already going on: no introduction, no nothing.”

People like you, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul and a couple of others represented a metropolitan or urban way of jazz as a lifestyle—as opposed to referring to Africa, like John Coltrane or Sun Ra did. I wonder how important it was in that sense to wear, say, a suit and not a colorful African garment onstage? I ask because your music was and still is also about style and body language. Everything, including the music, was and is glued together by coolness.

Oh yeah. Being a musician and wearing the suit was like making a social statement. Remember the times. Instead of getting up on a soapbox and protesting like some black poets were, we showed our pride with our body language and in the way we dressed. I certainly refer to a European tradition here in the sense that I say that Mozart was a jazz musician too.

How does he fit into that equation?

Just listen to his Symphony #40 in G Minor and you’ll understand. The melodic motif of this symphony is nothing else than a predecessor to the upbeat that you’ll find in a lot of jazz compositions. You see, I don’t stop at the word “jazz” as I don’t stop at words at all. It would have been most fascinating if Mozart had been born 150 years later!

That’s an interesting thought experiment.

To me the word jazz means: I dare you. I dare you for a meaning, for the moment I dare you. Expand on that meaning because human being means so much. It means so much that is not yet there. In progressing we become more and more human. You know, some people say it’s already done. We’re done, like as if we were a cake that came out of the oven. But no, we’re not. We’re everything we do. The conscious decision to wear a suit reflects the struggle within itself. Another conscious decision to keep the group I’m working with now sharp is to leave out rehearsals. It has a practical connotation as we all are living far apart from each other. But it has much more to it than just the practical.

To me this sounds like a continuation of Miles Davis’s working habits. He didn’t rehearse much either, right?

I remember Miles and me talking on the phone a little bit when I had just joined his quintet and he’d announced to me that we’d be going to the studio next week. At that time I had a book that I used to carry with me. I started writing music into this book during my stay in the army. So Miles said “We gonna record next week. Bring the book.”

Because he was curious?

Because he knew. I had shown it to him before, and he’d seen “E.S.P.” in it. That was in late 1964. We then recorded the album E.S.P. in New York in January 1965.

That was a landmark album consisting entirely of original compositions by what was to become Miles’s “second great quintet.”

Yeah, as I said, I’d just joined him. We actually played in West Berlin at the Philharmonic together in September 1964. But back then we didn’t have any original compositions yet. We were still elaborating on Miles’s repertoire, giving it a spin. I should mention Art Blakey at this point: Art always said that we had a message to deliver. That made us bullet proof. I mean, we were traveling all over in trains and planes and we had some close calls. Once a bus almost went over the cliff. But Art would always say that nothing is going to happen to us because we have this message to deliver. I mention this because Miles thought the same. But there were other important people in my life that have influenced me, too. For sure Art Blakey had left a strong impression on everyone he ever met. I remember him spending two or three hours playing with kids in Japan during a tour. And only recently I heard that some of those kids who are adults today say they remember Art Blakey spending time with them and that they want to thank him for inspiring them. They basically said that he enabled them in part to become strong adults and contributing to society.

There is no such thing as wasted time.

Right. And of course we all know that Art Blakey was self-destructive in his own way.

You mean because he was using?

[Pauses] That was not the whole man, the whole person. I was with Art for five years and with Miles for six. When I went to Japan with Art, I remember that we met some Japanese writers who urgently asked us the question: “What is originality?” That was in 1961 during my first stay in Japan.

And what was your answer?

Art said: “Originality is what jazz is.” You know, originality is not copying. So Art said: “Jazz means trying not to copy or trying not to repeat something from the past—bringing something from your own gut.” I like the phrase “the mystery of us.” Not only as musicians, but also as human beings we’re on this adventure called life. I always say life is the ultimate adventure of the mystery of us. I know there’s people who think “ultimate” means “end.” But I think ultimate means “unending.” No walls, no boundaries. The question is: how do you play that?

Wayne Shorter with Art Blakey (drums) and Lee Morgan (trumpet) in Chicago, 1961. Photo: Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images.

You mentioned that with your acoustic quartet you don’t rehearse. Obviously that takes trust. That’s where the real magic comes into play.

When we’re not on the road we spend quite a bit of time studying music; not listening to music but studying music, reading music. I read a lot of science fiction novels. At the moment I’m reading a book called The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi. The story takes place in the Thailand of the future and the windup girls are females who freed themselves from slavery and have to live in hiding. They call themselves “the new people.” By the way, last week five girls came in here to do an interview for a documentary on Stanley Clarke, and one of them was his niece. They were all mixed—Asian, Latina et cetera. And right before they left they said: “You know we are the new people.” The first book I read when I was twelve years old was The Water Babies by Rev. Charles Kingsley. Today I have about four or five copies. The first one was an abridged version for twelve year olds and only later I found out there was an original version, a more complex one.

Water Babies is also the title of an album by Miles Davis. Had he read the book as well?

I don’t know if he read it but I know that I gave the book to him as a present one day. He recorded Water Babies after I had left the band.

So everything is connected, but how do you connect with your musicians if you’re not rehearsing?

We always start with something we call “zero gravity.” We’ve been together for years now. We have a kind of unspoken communication, almost like E.S.P.. So, when one of us plays something, just one note—it always reminds me of going on a date, you know, a guy and a girl. Usually most dates go like this: The guy is thinking of what to say while the girl is talking and then she’s thinking of what to respond while he’s talking.

But that’s not really listening.

That’s why I say “usually.” But if they’re not thinking and just talking and the other one’s listening, then something’s happening. Even if they are disagreeing! That’s an adventurous date, and I would compare our quartet playing together to an adventurous date.

Or maybe a boxing match? I know that Miles Davis boxed—do you box as well?

No, I never did. But I like boxing. Nelson Mandela, who was a boxer too, hit it when they asked him how he put boxing together with his beliefs about compassion and non-violence. He said when he was boxing he and the opponent approached each other with the greatest respect. Plus he knew that his opponent had been medically examined. It wasn’t some gangster business, you know, when you throw somebody in the ring and he’s not ready for it. That’s when brain damage and all that stuff happens. Mandela said that practicing told him what to do outside of the ring—you know, take the boxing to the prison and fight the guards. Boxing to him was like a seed.

Joe Zawinul once told me that one really important thing about being in a band is that you have to get along traveling together and actually he extended this to the aspect of drinking together. Being together in the Weather Report also meant that you could always relate to each other because you had this common sensibility when it came to exchanging ideas. Do you have as intense a relationship with your new quartet as well?

Oh yeah! We travel together in good ways and my wife travels with me all the time. Only recently Brian Blade married too. He married the young lady he went to high school with. He hadn’t seen her in twenty something years before it clicked. They travel with us too. And we’ll get to the point where Danilo Pérez will join us with his wife too. They have three children but Danilo’s wife is amazing. She plays alto sax and she has a degree in music therapy. I wonder how that will turn out. All of us traveling together…

Bringing the wives on the road is the complete opposite to what Miles Davis wrote in his autobiography about traveling and never, ever taking women on the road. Seeing as how he’s known as one of the greatest and most prolific bandleaders of all time, is this a reaction or comment on his way of leading a band?

No, I wouldn’t say that. You have to know before Miles passed away I had my own band and we would both play at Montreux or some other place. He would go on first and when we met again in the dressing room, he’d ask if we should go on tour together—you know, from bandleader to bandleader. Back then I had Terri Lyne Carrington, a woman, on drums. And he would ask me if I thought women keep better time than men on the drums.

And what was you answer?

Terri was sitting right there, so I said something like women are really good with interior decorating and that I’d think that jazz needed some interior decorating. You know, women are integral to jazz. They may not stay in the forefront, but Miles used to say if you played to an entirely male audience you better get another profession. And that’s one of the reasons why he went into Bitches Brew: He wanted to get into the then uncharted jazz territory where people who liked Janis Joplin and other girls screaming felt thrilled. He was convinced that we knew better how to play this rock and roll. And in all honesty, I anticipated something was going to happen too. The key came to me when we were recording “Nefertiti” without any solos in it, just playing the melody over and over again. Actually it was Ron Carter improvising underneath. I just felt that this was the beginning of a revolution.

The electric revolution? Nefertiti was also the last acoustic album before Miles Davis went electric.

Several writers said that the repetition of “Nefertiti”, this groundbreaking new format, was a nudge into a different thinking. One night I was at Miles’ house while James Brown was having a residency at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. So, Miles was cooking and his new wife Betty was there too. And Miles, he said in his whispering voice, he said: “You know jazz needs another motor, it needs a motor like James Brown has a motor.” And while he was cooking he asked Betty to do a dance step that exemplified the motor. We would often stay in apartments where we could cook and all that, and he’d call our room and he’d say: “Hey Herbie, hey Wayne, come on over and check Betty out!” And then we’d walk into his apartment and they’re cooking and Betty’s dancing to Jimi Hendrix and James Brown and Sly Stone and she’s dancing the new kind of steps we’ve never seen before. And Miles says: “That’s what I’m talking about!”

So I guess it’s true that many important decisions are made in the kitchen while cooking?

I would say yes. Miles would always come up with new ideas in the kitchen and at the same time tease you to taste the chicken or the steak he was just cooking. The same applied to the hotel rooms we were staying: He’d order a lot of food before we’d go to the night club to play—two tables full. Then he’d say: “There it is.”

You ate before you played?

No, we didn’t. But he wanted to look at the food. He’d say: “Doesn’t this look nice?” He would call sometimes and invite me to the Cuban restaurant down the street from where he lived in New York, a place called Victor’s. And let me tell you about yet another favorite restaurant of ours on that corner of 52nd and Broadway right across from Birdland that served the best Wiener Schnitzel in town. Which reminds me, when Joe Zawinul and I met there he wasn’t speaking any English. We were talking with our bodies but it translated as words. That corner was something.

What made it so special?

It was like you worked in Birdland and during an intermission you’d go all the way down to the Village Vanguard. All the musicians would cross each other all the time. Actually it was the only time musicians would see each other because everyone was always working. Some of us would have our own cars. Lee Morgan had a Triumph and Donald Byrd had a Mercedes. Herbie drove a Cobra. If you didn’t meet the musicians on the street you’d see them passing by.

What car did you drive?

No car. I was in the army where I got my driver’s license but I never owned a car until I moved to California twenty-six years ago. And somehow all that goes into the music. What happened between Birdland and the Village Vanguard was nothing else than celebrating a way of life. But regardless of cool you’re always celebrating the wonder of life and you want to celebrate it by giving something back to life, which means to the people. And what you give is what your profession is, so in my case it’s the music. That’s actually the greatest thing you can give to life in celebration of the wonder of it. Music that reflects life is an original gift to people. To me that’s the meaning of life: You have to do what you do—whatever that is—with the maximum possible faith. Does something exist without people? Take the word “existence”: Is it a valid term without people? A tree falling in the forest—is there a sound if there’s no one there to hear it?

Now that you’ve been exploring the meaning of life in other ways, has your method of composing changed? How would you compare writing “Nefertiti” with the Miles Davis Quintet and writing “Orbits” from your last album?

What shall I say? “Nefertiti” came just like that. Almost effortless. Whereas writing music now is like… you have to realize that today is a different time compared to a couple of decades or centuries ago.

What’s the difference?

It’s not only about me and how easy writing a piece of music is for me. We also have to realize that we do what we’re doing with uncompromising faith. We are living in a century where the financiers are not reading poetry anymore. We therefore have to surprise the financiers how we get things done that touch the human spirit without their money.

And this understanding influenced and informed your way of composing your late music? On Without a Net you let classical music theory and abstract ideas infiltrate into your music. What you are doing is not pure jazz anymore. I have to mention Miles Davis once again as he was listening to a lot of Shostakovich when he went electric and that basically informed the way he composed. How would you describe the directions you’re taking with your quartet at the moment?

If jazz sounds like jazz it becomes like a statue: immobile. But the intention of jazz is to move forward. I dare you to go forth. Exactly that is often forgotten. Doing what we are doing is a risk. But it’s first and foremost a chance. You have to come out of the closet during your life as a human being when the coast is clear. That’s what we’re all doing. See, we’re not playing music—we’re dialoguing with life. There’s a difference! We’re having a dialogue with the unexpected. If we can take chances on stage, it all gets down to the definition of faith. Do you know that people have been trying to define the word faith for ages now? They’re still trying to define it! What is faith? Some say it’s something that adapts. Others say it’s something not seen. Faith is the evidence of something not seen. But to me that’s limited. If you ask me, faith is to fear nothing. When you play music, when you embark on a plane. You get on fearless.

That leaves me almost speechless in light of the experience you went through losing your wife in the tragic TWA Long Island plane crash in 1996.

My wife.

I hope I’m not crossing a line here by mentioning this.

Don’t worry, you’re not. Because I believe that death is temporary, like so many things that are temporary. And that implies that you can detach yourself from that and fly and you’ll meet more than what you’ve lost. And that means with anyone who’s died you’ll more than meet them again. I say it again: Be fearless! I know, it’s easy to say. You got to work hard on it, no doubt. But never forget: We work hard on the other stuff all day long. Just take a look around you. We work hard gossipping on the phone or on the internet for instance. You can always use your time more profoundly. ~

This text appears in the forthcoming Electronic Beats Magazine N° 38 (2, 2014), out June 1st. You can purchase the new issue, and back issues, in the EB Shop. The Wayne Shorter Quartet, featuring Shorter on tenor and soprano sax, Danilo Pérez on piano, Brian Blade on drums and John Patitucci on bass, will play the upcoming Electronic Beats Night of the Jazzfest Bonn on June 1, 2014. The show will be made available soon after on www.electronicbeats.net.

Published May 28, 2014. Words by Max Dax.