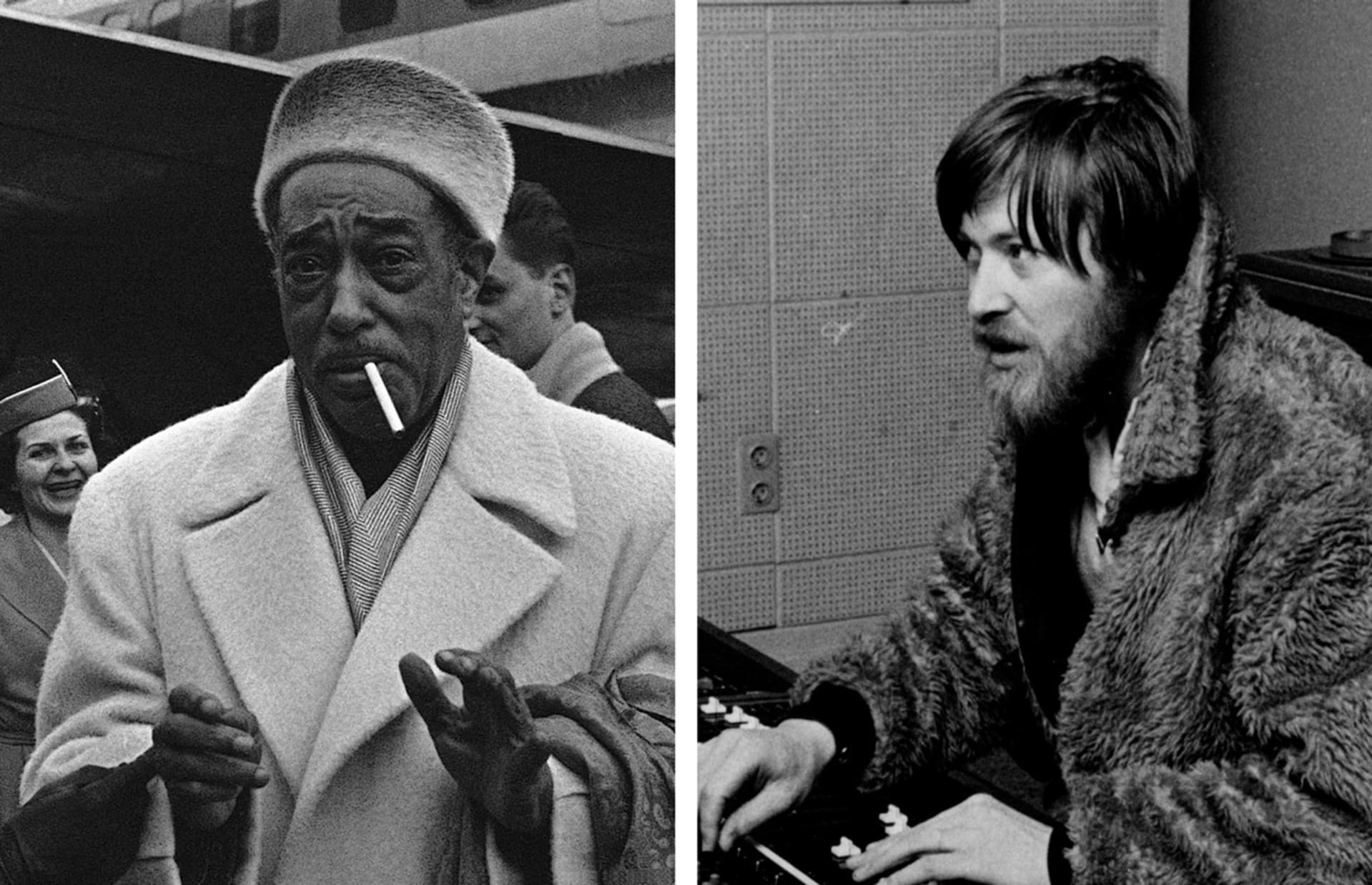

Two Descendants of Musical Legends in Conversation

Duke Ellington wrote more than a thousand compositions in the five decades between the 1920s and ’70s, which makes him one of the most prolific musicians in jazz history. Most of the pieces have been documented and released, so it comes as something of a coup that Grönland Records will debut previously unreleased recordings of the Duke on July 10. Furthermore, the music was recorded by none other than German engineering legend Conny Plank, who famously produced Kraftwerk, D.A.F., Harmonia, Cluster and many more.

While on tour with his orchestra in April 1970, Ellington recorded two songs at Cologne’s Rhenus Studio with Plank, and the sessions turned out to be a decisive moment in the young engineer’s career. About 40 years later, Plank’s son Stephan discovered an old tape while sorting his father’s archive and realized after some research that it was the studio session with Duke Ellington, which he titled The Conny Plank Session. We invited him to chat with Paul Ellington, the grandson of the Duke and head of the Ellington estate, about taking care of their families’ legacies and how the release of this unheard treasure came about.

Paul Ellington: I grew up not far from you, in Copenhagen. At 15, I moved to New York. My dad [Mercer Kennedy Ellington, Duke Ellington’s son] was still alive. Two years later, when he passed away, I took over his orchestra for a while, and when my mom passed ten years later, I took over the Duke Ellington estate. It’s a challenge because people tend to forget about him, and I want them to remember him and his importance to American history.

Stephan Plank: My father [Conny Plank] was more or less forgotten when I took over his estate, but his work is slowly coming back to Germany. He was far better known in countries like England or the US. At the moment, I’m working on a film about my father, which gives me the chance to see him from a totally new perspective. He died when I was 13 years old, and I knew him as my papa, but I don’t know the producer Conny Plank.

My father and mother weren’t hippies, but we lived on a big farm in the middle of nowhere close to Cologne. That’s where my dad had his studio, and all the musicians who came to record would live there during those sessions. We would eat at the same table and share the same bathroom. For me, the musicians were like my playmates. By talking to the artists who worked with my father, I’m trying to find out what he was like as a producer.

PE: I’m actually doing something quite similar. I went back to school for film three times, once for film production, once for screenwriting, and then for a graduate program at NYU. Since 2007, my main project has been my grandfather’s life story. I think a movie is a very important way of reminding people of how and what a certain person did in their life.

SP: My father was such a big fan of your grandfather. He had a very deep love for jazz music. I’ve known the story of him working with your grandfather since I was five years old. My father told me that he was really nervous when your grandfather wanted to listen back to the recording, and after they did, your grandfather said, “Young man, you’re making a good sound.” For him, at the very beginning of his career, it was the equivalent of receiving a diploma. My dad was like: “Okay, now I’m a sound technician, because the Duke said so.”

PE: That’s very cool. My dad had me when he was 60, so I didn’t come until much later than a few of my other siblings. But he certainly told me loads of stories about his father.

SP: What was it like for you to listen to the recording my father did of your grandfather in 1970 [The Conny Plank Sessions]? I was a little bit shocked when I realized what it was. After my mother died in 2006 I had to clear out the studio and take care of my dad’s archive. In 2010 I moved to Berlin and started to put everything in order, and suddenly I had this tape in my hands. I realized it had to be the tape my father always told me about.

In order to make an old tape listenable again, you have to bake it in the oven so that it doesn’t get destroyed. When I was finally able to listen to the music for the first time, I instantly recognized Duke Ellington. But somehow I heard my father in there as well. I just had this feeling that I was listening to one of the missing links between jazz and krautrock. I think my father was very much inspired by your grandfather.

PE: And my grandad—as far as my dad told me, anyway—really appreciated when the people working in the studios knew what they were doing. If he had that kind of conversation with your dad, it means he must have really liked what he was doing.

SP: Was your grandfather known to be very precise when it came to recording and sound?

PE: In the early days, he would work the musicians so many hours that eventually they were just like, “I gotta go,” and leave. He would do this at live performances too, when they’d already done two hours and he just wanted to play more. There were times, apparently, when he was alone on the piano at the end of the night. He was a bit of a perfectionist, and as soon as he thought [a piece of music] was right, he would move on to something else.

I don’t like all of his music, and maybe that’s blasphemy to say. I know it’s all very intelligent. But what I find fascinating about his work is that, from the late ’20s and ’30s up through the ’60s, his compositional style kept changing. Most of the time it’s amazing; at other times I wonder if people who aren’t musicians would appreciate it. But that exploration is really what made him stand apart.

SP: My father had a similar view. When he was recording with jazz musicians in Cologne, he used to get frustrated because it didn’t always sound the way he wanted. He thought he was doing something wrong, that he wasn’t working the desk in the right way or didn’t have the right microphones. But this all changed when your grandfather appeared, because he realized it wasn’t him—it was the musicians. From then on, he helped give birth to new styles of music. While doing the research for the film, I found out that my father recorded Whodini, an early hip-hop and electro band from New York. I also discovered that he was the original recording engineer on “Marmor, Stein und Eisen Bricht” by Drafi Deutscher, which was a massive German pop hit in the mid-60s. Those two acts are so far apart, so it makes you wonder how he got from one point to the other.

PE: That’s what makes it interesting, right? I don’t know if you feel the same way, but being related to a person like this and finding out that kind of information is almost like getting to know somebody all over again, and I think you touched on that earlier.

SP: Suddenly, the person gets fleshed out. You have a certain picture of him in your head, and then you listen to the music, and since music transports lots of emotions, a new part of him comes to light. You find the stepping stones between krautrock and electro and hip-hop; you see how he went from recording The Eurythmics to the Bläck Föös, a very famous folk band from Cologne, and on to Ultravox and Echo & the Bunnymen. Your grandfather and his comments gave my dad the confidence to do all the stuff he did.

PE: You said you found the tape, which had to be restored. Did you know by then that it was unreleased?

SP: I didn’t know it was unreleased material. After I listened to it I thought, “What do I do with this?” After listening to it again three months later, I decided that I had to find a person who is an Ellingtonian, a specialist. So I went to see this guy and asked him: “May I play something for you that you’re not allowed to tell anybody about?” Of course he agreed, and it turned out that he hadn’t heard the material yet, either. I knew then that I had to do more research. I was lucky that my father put the date it was recorded on the tape’s case, so I had a reference point. I talked to the people at the studio in Cologne, and the dates matched with the Duke Ellington sessions. So I took the recordings to Grönland, which is the label of [German pop star] Herbert Grönemeyer. I was a little secretive and only said, “Listen to this. It was recorded by my father, but it’s not what you’re expecting.” [Grönemeyer] said, “Is this what I think it is?” And I said, “Yes it is.” And then he said, “Okay, we need to release this.” That’s when we contacted your grandfather’s estate.

PE: That’s amazing. I can’t wait to hear it. You were talking about baking old tapes—I have about 88 reels that my dad left me, and they’re all from the late ’30s up to ’74. I know for a fact that if we’re going to try and do anything with them, it’s got to be done very carefully. You should be really proud of what you were able to accomplish, because it takes a lot of work.

SP: I did a lot of research. There’s a really funny web page, Gear Sluts, where studio technicians meet and have long discussions about how to bake old tapes. I was lucky enough to find someone here in Berlin, and when I told him that I needed to rent his oven, he looked at me as if I was mad. You see, it was a real bakery oven, so you can program how the temperature rises and falls really precisely. But we were only able to do it on certain holidays in Germany when the bakery was closed for two days.

Published July 09, 2015.