Two Female DJs Fight Sexism in Dance Music

Umfang has gotten a lot of press.

Over the past year, the New York City-based producer and DJ has appeared on music outlets like Juno Plus, the FADER and THUMP as well as broader-interest publications such as the Hairpin and Forbes. But only a few of the clips focus on her fearless DJ sets or the killer cassette she released in August via the 1080p label, Ok. Most of them spotlight—and all of them mention—her work as a member of Discwoman, a collective that organizes all-female parties called Technofeminism and runs a website devoted to interviews with female-identified talent.

Although their activism has piqued a considerable amount of attention in and outside of club circles, Umfang and her Discwoman cohorts are not alone. 2015 has seen the launch of several grassroots efforts to change dance music’s prejudiced tides, from The Black Madonna’s female-oriented DAPHNE party series at Smart Bar in Chicago to the launch of the Yorkshire Sound Women Network and the inauguration of Berlin’s Salt + Sass event series. Earlier predecessors to Discwoman include Your Sister’s House, a weekly empowerment-oriented party in San Francisco that launched in 1993, and female:pressure, an ongoing database of women in electronic music and digital arts that Austrian producer/DJ Electric Indigo founded in 1998. With this heritage in mind, we connected a stalwart activist and artist with an ambitious ephebe who’s carrying the torch.

UMFANG: Hi Susanne. I don’t really know anything about Electric Indigo. By the time female:pressure was exposed to me, I didn’t know who started it; I knew that it was a woman or some women. I knew that it was really great and that it was doing something that I wanted to align myself with. But I didn’t know about the beginning of it or how it started.

ELECTRIC INDIGO: For me, it’s a success if people know female:pressure but don’t know that I am behind it or who I am, because I don’t want to be the only face that represents it. Basically, I started to DJ 26 years ago in Vienna. A year or two later I learned about the record store Hard Wax in Berlin and decided that I definitely needed to work there. So in 1993, I moved to Berlin and worked there for three years. That’s when my DJ career really started, and since then I’ve DJ’d in 37 countries. When I started to DJ, I did not think that it was special because I’m female. But everybody around me noticed, and people usually made comments or asked me, “How is it to work in this male-dominated field?” Or they said something—you know, supposed compliments like, “You’re really good for a girl.” I was forced to deal with the gender issue, and my answer to it was usually to list names of female colleagues. I noticed that people didn’t know about female DJs and that there was a total lack of information about female artists in electronic music. I thought it would be super practical to have an online database for female DJs and producers, and I could refer to it when the next person asked why there aren’t any other female DJs. Meanwhile, female:pressure is not just an online database with approximately 1,520 artists, visual artists and researchers from 66 countries around the globe; it’s also an active network and mailing list.

U: Last September, two friends and I decided to do a festival in NYC of all female DJs because we knew so many great ones, and female:pressure was brought to our attention pretty quickly. We did two days of bookings with all female DJs, and we got a huge response from press and from the public and a big turnout. We didn’t really think that it was an innovative thing to do, because we thought that society had moved past this, but once you do something in public and speak about it, you realize people are comfortable coming out of the woodwork to talk about how they do feel underrepresented. We realized that we couldn’t stop and started planning more events. For the first one, we donated our profits to a womens’ empowerment nonprofit, and that’s part of the model of the Discwoman events. Many people have reached out to us to say they’d like to do the same thing in their city, and that ours was a good model for what they wanted to do.

EI: When you organize parties with so many female DJs, do you pay them?

U: The first festival was a donation of time, so everyone played a one-hour set and they were not paid. But in the last year we’ve found that one of the most powerful things we can do as bookers is to get women paid for what they do. We aim to infiltrate the scene at every level so that at no point does a woman need to be in an underdog position to a man.

EI: I think that’s very good thinking. I’ve seen this so many times, even with my own work: everything that’s related to “the good cause” creates so much voluntary work that you almost necessarily start to lose track in your business world. To remain healthy, I think it’s really important that it somehow adds to paying the rent.

U: Three of us make up Discwoman: I’m a DJ and a producer, Frankie is a social media wizard and she runs the agency part of Discwoman and Christine is a businesswoman and event producer. We’re still all learning because it’s still been less than a year, but I think you’re totally right. We had this initial vision, and then quickly realized we needed to figure out how to pay ourselves because it’s been so much work to do events all the time. We’re still figuring out ways to get money, and that makes us compassionate toward the people that we’re working with. If we’re going to call upon women to participate in our events over and over again, we want them to feel like they’re a part of this monetarily and that they’re valued, not just the face of our product. They’re a part of this thing that’s really working and taking over.

https://soundcloud.com/umfang/technofeminism-live-part-i

EI: What exactly is the formula, apart from an all-female lineup? Or is it that? Does it have to be 100 percent female?

U: In our mission statement, we define it as “female identified.” We don’t want that term to become alienating. There are a lot of complicated identities, and we want to be open to that. That’s welcoming to anyone who feels respectful of the mission statement and identifies as woman or something similar. We don’t want to draw really harsh lines, because I think that’s going against what the spirit of it is. If you feel marginalized and you have some part of female identity, we want you to feel welcome.

EI: I defined female:pressure as “female identified” as well, without calling it that way, because it started 17 years ago when queer theory was not everyday business like it is now. But there are quite a few artists in the database, and some whom I’ve never met personally and I don’t know what their biological sex is. It raises some interesting questions, and it can become complicated if you go deep into that issue. In general I keep the ideology of female:pressure as open as possible. There are so many people involved with so many different views on the world and on feminism. Maybe there are even some artists listed who have a problem with feminism. So I try to keep the ideology to a really small amount. Apart from raising the visibility of female-identified artists, there’s not so much of a mission statement with female:pressure. We don’t have clear rules and we don’t have a clear structure.

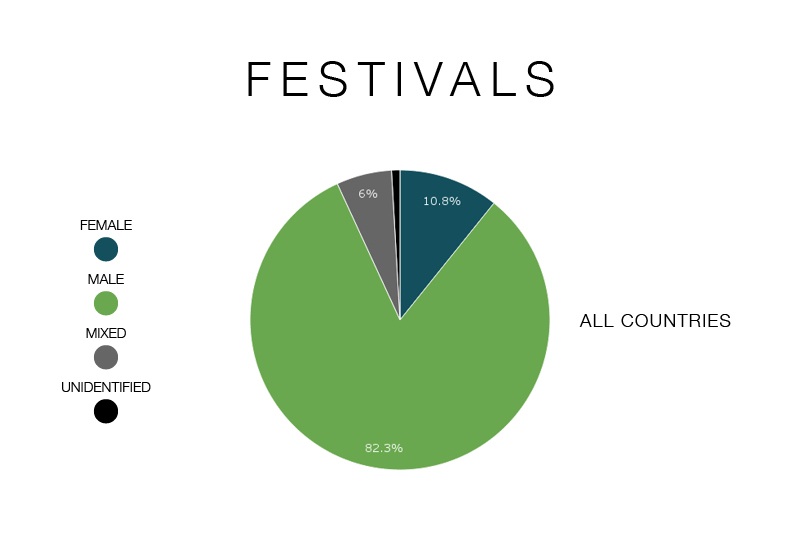

U: Female:pressure has been so widely shared that I don’t know if I was aware of its existence until after we did our first event. I do remember that my friend Michelle [Lhooq] at THUMP mentioned graphs similar to those from female:pressure about how festival lineups are mostly male.

EI: We put a lot of work into our study; a lot of people contributed. The most common defense against the fact that lineups are heavily male-dominated is that people say there are very few female artists, or that the number’s smaller than the number of male artists. Or they say there are very few good female artists. The only thing I can agree with is that the absolute number of female artists in this field is probably smaller than the absolute number of male artists. But because nobody ever counted all the male artists, either, we’re assuming. Nevertheless, it is also my own impression that there are fewer female artists than male artists, and that has a tradition and there are reasons for that, too. When it comes to programming and curating, I must say—out of personal experience as well, as I curated [Popfest,] a large open air festival in Vienna, Austria this summer—it usually takes a bit more research to find a fair number of female artists and more risk. If you play it safe and book artists who are already very popular, you usually have to book those who have the most media representation, and they are mostly male. I think it’s changed a bit in the last few years, as there have been several waves of women popping up in music media and then disappearing again. As a curator or promoter, you have to have more imagination and you have to dare a little bit more if you want to have fair representation or diversity.

U: Yeah. It seems like people still have an idea of what is “normal.” If a festival lineup was half male and half female, it would still be remarkable instead of equal. Instead of that being normal, that’s still thought of as significant.

EI: And when a festival lineup is one-third female, both male and female observers or artists themselves think it’s 50/50. Have you noticed that?

U: Yeah. I think it’s good for me to acknowledge that I had my own doubts about doing all-women events, and I had my own negative thoughts about women as talent. Even I, a female DJ who is now promoting female DJs, was very hesitant to get involved in an all-woman event and an all-woman business. I’ve had to change my mind, I’ve had to be proven wrong over and over again. Women can play well, they can play hard techno sets and they’re not just going to play pop or delicate music. Now that I’ve seen it work over and over again and I’ve been exposed to how amazing all the women we work with really are, I believe it.

EI: For me, all-female events totally depend who is doing what for which motives. It can be totally cool for me to take part in or to see an all-female lineup, but it can also be super tacky and almost disgusting. It really depends who does it, what the history is, where it’s going and who is involved.

U: Sometimes women decline to work with us. But most women, at least in New York, are really excited to get an opportunity to showcase their talent. At my Technofeminism party, I try to book women who aren’t getting a lot of attention and are underrepresented, underbooked or haven’t had the opportunity to play their stuff live before. So I think a lot of those women are really stoked to get that opportunity in a really respected venue. The only people who have refused to work with us are very or relatively accomplished.

EI: I totally agree.

U: It’s like, once you start getting a lot of attention for who you are and you’ve done it on your own, women are very afraid to lose that respect. I know I was. I think I never acknowledged ever being oppressed in any way because I worked so hard to be technically good so that no one ever talked about how I am a woman. I think if you’re already accepted by men for what they do, sometimes you don’t want to lose that.

EI: Yeah. I find it very sad—and this is an observation I made several times as well—that relatively famous or successful artists often have a problem with showing solidarity or supporting other female DJs who are not there yet, as if they would face some danger. Maybe they’re afraid of showing a certain amount of political attitude in an opposing field. But shutting up never will change anything! If you sit there and wait for those in power to let their power go, you will probably wait very long.

U: I think that’s true. I ran events with a majority of women for years with almost no buzz. Once I named it Technofeminism and started talking about it in interviews, everything exploded. It’s insane what a difference that made, and how much people are encouraged to speak up once they have a platform to do so. I think it’s really important to talk about it, and to do things to help. Susanne, it’s so exciting to have you on the phone. Can we reach out to you in the future?

EI: That’s so funny, because I wanted to say the same to you. It’s so exciting that there’s this new project from New York. It would be an honor to have you listed on the database. We should definitely connect.

The next Technofeminism party takes place on September 2 at Bossa Nova Civic Club in Brooklyn, New York.

Published August 26, 2015.