Budapest’s UH Fest 2017 Showed Why Politics Matter To Music Scenes

A Saturday public artist talk at Budapest’s experimental festival Ultrahang (UH) eventually settled on a familiar topic: the intersection between politics and underground music. Up until then the conversation between the moderator and the three artists featured—Nicola Ratti, Andrea Belfi and Kara Lis Coverdale—touched upon a number of standard interview topics. The introduction of this new theme arose via a mention of the feminist electronic music network female:pressure. Coverdale seemed to expect this angle. She described the evolution of her relationship to this always-evoked subject from refusal to engage to resignation. “Existing is political,” she politely explained about how she came to terms with the unavoidable politicization of her career. “All you have to do is just live” and you will find yourself embedded in political contexts.

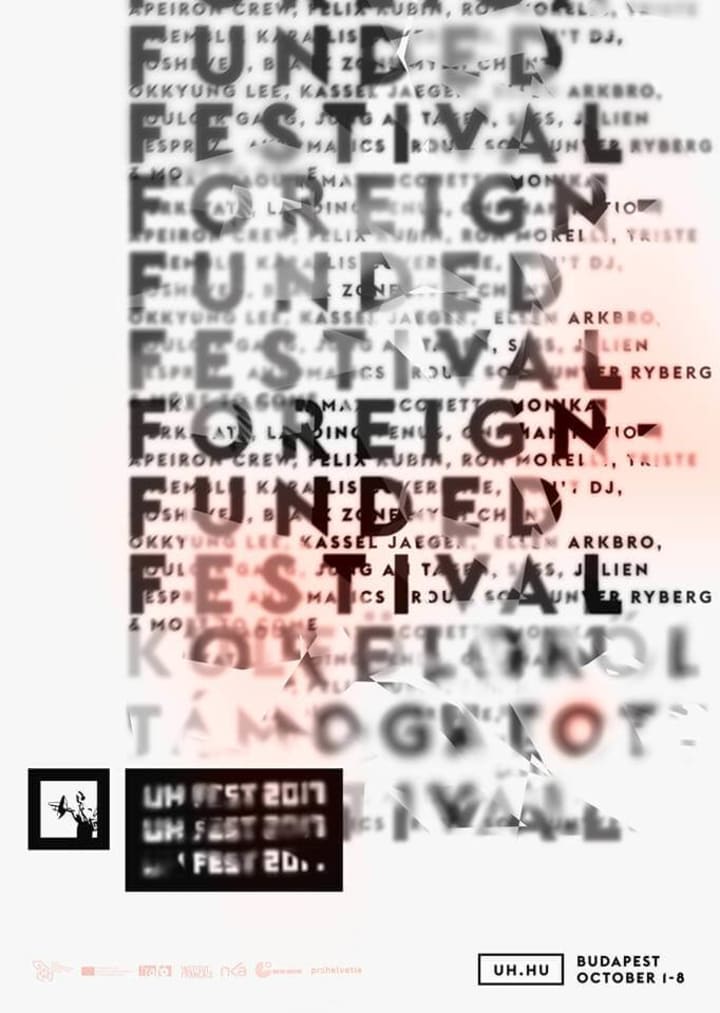

Anyone who spent even a day at this year’s edition of the modest-but-killer weeklong festival UH Fest would likely be confronted by political issues. The rising tensions in Hungary that resulted from a series of xenophobic and nationalistic moves by the country’s ruling party, Fidesz, have forced even underground musicians to reckon with issues they once avoided. UH made them the central theme for their 2017 edition when they revealed their flyers in a September 6 Facebook post; the names of the artists on the lineup were obscured by the words “FOREIGN FUNDED FESTIVAL.” This was a political statement that responded to a new law passed by the Hungarian parliament.

The legislation requires all non-government organizations (NGOs) that receive more than €24,000 in funding from an international source to register in court and identify themselves on promotional materials as a foreign-funded NGO. Since UH is organized by the not-for-profit Ultrasound Foundation, they could be affected by the regulations. So they decided to make their posters a statement against what the measure represents to them: the latest hostile move by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s regime toward what it considers to be foreign agents manipulating domestic organizations to aid opposition parties. “This new act, besides being an unhealthy example for other countries, creates a chilling effect on self-organized active citizens and is against what we have embraced and promoted throughout our almost two-decade activity,” wrote UH.

The government’s efforts to villainize NGOs started in 2014, when the Prime Minister gave speeches maligning them and ordered a controversial audit to prove those foreign-funded non-profits were doing the bidding of opposition parties. Since NGOs provide one of the only sources of aid to marginalized communities in Hungary and refugees, they represent one of the only viable avenues for a concerted effort to confront Orbán. In this context, NGOs see the actions against them as part of a broader agenda to squash potential political resistance. Over the past two years, some have come to understand this as a threat to Hungarian culture, including Budapest’s underground music scene. If Ultrasound Foundation becomes illegal or loses funding, UH Fest may never happen again.

The flyer design was therefore also a statement of solidarity with comrades in the resistance. They also hosted events at spaces like Gólya, a cooperative café, bar and cultural center where the closing ceremonies took place on Sunday afternoon. Goodiepal, who confused me in a good way at UH 2015, returned for a screening of a film made about him and an hour-long talk with the audience. It touched upon the eccentric artist’s critiques of the rising xenophobic tide in Europe and his mysterious activities helping refugees in Belgrade, Serbia, where he is currently based. He declined to say exactly what he was doing there and joked that he was smuggling people behind his belly.

The dire political circumstances in Hungary have galvanized people in Budapest and generated increased interest in UH. While the festival has grown at a slow but steady rate since it began in 2000, attendance and volunteers spiked thanks to coverage in the Hungarian media following the revelation of their 2017 flyers. According to organizers András Nun and Krisztián Puskár, all of the UH functions drew bigger crowds this year, and the festival grew about 40 percent overall. Even the more intimate, low-key nights early in the week brought out about 200 bodies.

This was a dramatic increase from previous years. I noted in my 2015 review of UH that most of the events to take place throughout the week drew between 50 and 100 people, and the weekend party at the club Lärm relied on tourists wandering in to fill out the dance floor. But the contingent of incidental walk-ins seemed to be considerably smaller at this year’s Saturday night there on October 7, which starred SHAPE-affiliated Danish DJ crew Apeiron. Instead, it felt more like a significant event for the small Hungarian electronic music underground that consequently attracted many of the locals involved therein. Even J. Mono, who I was told is a gifted but hermitic artist, came out to play the opening set.

The political situation in Hungary energized not only UH Fest, but the Budapest underground music scene in general, Nun and Puskár told me. More local artists, promoters and venues who previously considered themselves apolitical have recently taken explicit stances and engaged with current events. After all, what choice do they have? Artists, publications and others involved in western European and North American dance music communities are debating whether dance music should “stop being so political” and if politics is an invasion of an escapist haven. For the reactionary contingent, such talk violates the fundamental values of dance music, which are usually described in decontextualized, vague platitudes like “togetherness” and “love of music.” Meanwhile, Hungarians are forced to come to terms with the fact that the very existence of a dance music culture is at the mercy of political realities.

But this politicization has not divided the Budapest scene, as critics of the increasingly frequent conversations around social justice movements in electronic music contend. The prospect of defending their underground culture from extermination united various factions of the underground music scene and volunteers from without to support UH Fest 2017. It poses a question to those in countries west of Hungary who discourage music fans from connecting political context to the culture they’re invested in: If now is the time for dance music to stop being so political, when will it be time to begin?

Read more: Overlooked experimental festival UH Fest 2015 reviewed

Published October 13, 2017.