One Love: Generations Of UK Sound System Culture Collide

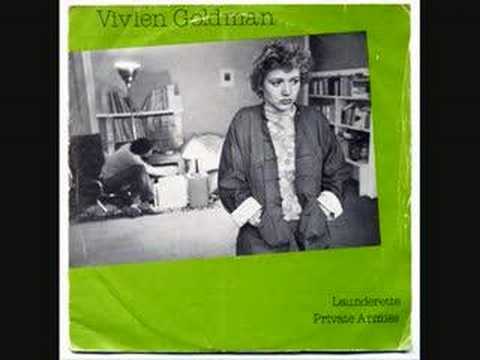

Vivien Goldman makes a striking first impression. When I first entered her classroom, she addressed the students wearing plaid checkered pants and a black shirt with flames coming up from the bottom and the word “Jamaica” written in rasta-colored Coca Cola script. She introduced herself as the “Punk Professor,” a name she picked up at New York University that references her background as a North-West London anti-establishment musician and NME writer. She lived with the avant-garde punks at London’s Ladbroke Grove and on Bob Marley’s compound at 56 Hope Road in Kingston—she later wrote a biography of that reggae icon. Her latest work is an LP, Resolutionary, that compiles output from her years as a member of the wave-y dub-influenced band The Flying Lizards and as a collaborator with dub legend Adrian Sherwood and dub techno pioneer Moritz von Oswald.

Those latter two producers connect Goldman to contemporary dance music, and to Mala. He’s a seminal contributor to the sound that is now known as “dubstep.” The South Londoner entered UK sound system culture around when Goldman left for New York. As a teenager he got involved with the local jungle and drum ‘n’ bass scene, which later informed his work as a member of the groundbreaking dubstep crew and record label DMZ. He now travels the world infusing his sound with influences from other cultures and countries. After releasing Mala In Cuba, an album that fused 140 BPM beats with Cuban rhythms and instrumentation, he’s presented Mirrors, an album recorded in Peru. His outernational leanings and roots in London’s rich history of sound system music makes him part of the same lineage as the Punk Professor, and with both of them offering landmark releases, we figured there was no better time to unite them.

Vivien Goldman: I’ve checked out Mala, and I see where we have points of contact and why you thought it would be interesting if we spoke. For a start, I see that you’re coming out of dub and reggae, aren’t you, Mala?

Mala: For sure, yeah. I was born in South London, and obviously the sound system culture in London has been massive for decades. I grew up through that lineage: Jah Shaka, Aba Shanti-I, Channel One, and then the jungle era. Jungle was really my first love, and I see it as a continuation of dubplate and sound system culture.

VG: And you believe in a “music for healing” aspect?

M: For sure.

VG: That’s something that I’ve been really drawn to. I was lucky that, when I started out writing about and working with people like Bob Marley, there was very much a sense of mission in the music. The message was carried in the rhythm, but it was especially focused because the lyrics sent the feelings in a specific direction.

M: Being in London at that time must have been exciting and challenging. I guess that gave you and the musicians the fuel for that kind of consciousness and uprising.

VG: Are you saying that you think it was more confrontational then than now, because of the youth tribes fighting in the streets and all the conflict with the police?

M: Not necessarily. I don’t know because I wasn’t around then.

VG: Every generation has its struggles. And in a way, it seems even more convoluted and opaque now than it was then. Knowing your enemy seemed simpler then. But I think probably the big difference was that back then it was more illegal. There was no way those first generation Afro-Brits could have rented a straight place in the West End. There’s probably illegal dances now, but then quite a lot of it was an illegal subculture because it happened in shebeens, which were basically squats. Jah Shaka would play at the Bali Hai in Streatham. I don’t know if that’s still a venue or if it even exists.

M: I don’t think it’s there anymore.

VG: Oh man, that was an incredible venue because they had a sort of tiki-kitsch. It had these big statues, like those mugs that they used to have for ‘50s cocktail sessions. It created a slightly surreal environment for the steppers; mainly Rastas doing full-on, militant stepping.

M: Was it a mixed audience back then? Or was it predominantly black or white?

VG: I think it was predominantly black, but there was a chunk of white. There was never any hostility or anything like that.

M: Okay. I asked because a lot of the dances that I go to now where these same people play are the other way around—and with the youngsters as well. I remember jungle parties in the ‘90s being very mixed.

VG: They still have sound system sessions, don’t they?

M: Yeah, there’s a few that still go on, and they bring out the sound systems for them. We did a session last year in Bristol where we tried to combine the older and contemporary stuff, because so many people in the audience that’s coming out now are 10 or 12 years younger than myself, and a lot of them don’t necessarily know about the roots of where we come from. As much as we entertain, we think it’s important to try and send a message and educate about what’s come before us as much as we can.

VG: That’s great! You can definitely see the flow through the generations—in fact, I’m about to teach a course at NYU called Dub Nation: From Dub To EDM.

M: How do you see the development from dub to EDM?

VG: It never occurred to me not to! It’s just a family tree. I saw it happen; I moved to France in the ‘80s for some time, then I had a few years in England, and then I came to America, so I had a fractured experience of UK nightlife. But I did see a few generations of it. I think it was basically West Indian communities who got it going. There was a real leader in the community, Sean Oliver, who came out of sound system culture and put on some of the first raves in warehouses in Kings’ Cross. And then in the ‘80s, a bit after post-punk, Dirt Box started. That was a whole scene in the early ‘80s when I was moving to Paris. People used to dress up and wear zoot suits to those parties. It was the nightlife of the time, and it centered around early synthesizer music. Dirt Box wasn’t really dubby, but everybody involved in it had come out of that because it formed the culture for an entire generation.

Anyway, we don’t need to get into decades of club history here—the point is that at that time, the whole idea of dub and its whole vibe was about militancy and spirituality. I was in the Flying Lizards, and we came out of experimental jazz because we were in the London musicians’ collective of improvisors and so on. We married new wave-y synth pop with early electronic music, but it was all grounded in reggae and dub, because those were the first types of music to use the studio as an instrument, so it inevitably became the foundation for what came after it. Likewise, what you’re doing now is also steeped in reggae. But I don’t know if you’d file yourself under “EDM”? I’m using that as a loose, umbrella phrase in my course title.

M: Hmm. I don’t know. I don’t think people would put me under that umbrella, but at the same time, it is electronic and it is music. So maybe they would.

VG: Do you think I’m using “EDM” too broadly?

M: I dunno. To a lot of people in my world, “EDM” represents that big, stadium electronic dance music, which is often more progressive house-orientated—not necessarily the music you’d hear in a smaller dance in Brixton. “EDM” almost feels like a different culture than what I feel like I’m involved in.

VG: Do you file yourself under something?

M: I guess the music genre that I’ve been filed under is “dubstep.” But even that wouldn’t be…it’s not something that I’ve ever called my own music. I’ve never really put myself in any kind of bracket, and that’s because, by telling myself that I’m such-and-such a producer, there’s some sort of limitations that come with my approach to what I’m doing.

VG: I’m sure you try to resist it. All my life I’ve seen this resistance that everybody has to be filed under something. But when you’re a writer trying to convey information, sometimes you do struggle and try to put a name on something just to make it more accessible. There’s a lot of talk in the university system about appropriation and wanting people to stay in their own little boxes, but I see us all as more outernational. Anyway, the more fine cultural associations of EDM interest me, because I was just using it as a catch-all to describe things that weren’t acoustic and were made for people to dance to.

M: Yeah, I get that.

VG: So one would file dubstep under that. But maybe I have to rethink my nomenclature? Is it regarded as very laddist or a bit chav-y?

M: From my point of view, EDM just represents big stadium music: your David Guettas, that type of stuff.

VG: The more commercial end.

M: Yeah. I have no problem with it, but I don’t think my audience would say I’m EDM.

VG: I get it. I was just looking for a broad, one-word generalization for the title of my course. Dubstep goes with grime to me, and every time I come back to England I see it as a continuation of the shebeens and sound systems. But I see the difference between that and Skrillex. I left England when all my mates were starting to go to raves in fields, so I was aware of what was going on in British nightlife, but I wasn’t steeped in it the way I was with early sound system culture.

M: Yeah, dubstep and grime were definitely continuations of that. What really inspired me and made me want to get involved in music was listening to jungle. Only a certain DJ had a certain selection of dubplates, so there was that exclusivity and competitiveness between certain DJs, crews and sound systems. I’m 36—born in 1980—and in 1994 and 1995 there were a lot of under-18 jungle raves in London. I actually started playing at those clubs with big jungle DJs as a kid. It just had that feeling that there was nothing else in the world going on like it, and that was really exciting.

There was also a sense of community because you had to listen to the pirate radio stations in order to find out where the dances would be, or you’d have to go to the record shop to find out what the music was. But a lot of it was on white labels, so you had to wait in the record shop for half a day while the guy behind the counter played all the tunes. There were different tiers of customers—big DJs, then not-so-big DJs, and we were at the back of the queue because we were just 14 or 15 years old. But that sense of community was really important, and the record shop and the dances really brought it together. I have fond childhood memories of going record shopping and picking up flyers and seeing what records we could buy.

VG: I very much did that as well. I was lucky because we had a dub vendor downstairs from where I was living at Ladbrooke Groove, and bands would come in for pre-releases, and on Thursdays or Fridays we’d all be there. I think that community aspect is important to mention because to me, one of the biggest issues coming up now is the physical withdrawal that happens with a virtual community. My students have told me that many of their friends or people they knew have attempted or committed suicide due to a feeling of isolation, and I think that shows what an important role you play when you go out and play dances, Mala, and spread the community. People need connection. I used to say how dub reflected our fractured society at the time, and now in a way we’re even more fragmented, so we need more material to bind us. It’s been a thread throughout my life: the belief that music can have a role to play in building a stronger community where people can have more understanding.

M: It’s such a noisy world that we live in, and with all the madness, music was the thing that I could come to and find that silence—a meditation. I never thought my music would be dance music, because it was almost like when we was making it, we was stripping everything out, and it was what I wanted to listen to in order to relax after a heavy day at work. So it was surprising when people started playing it in the dance, and people started moving to it.

Music was always something that took me very deep within myself. I remember growing up in London and asking those questions that young people do: Why does society say that I need to get a mortgage and a car and get a certain type of job when I don’t feel that those things are important to my life? Music—Bob Marley, people from the roots and reggae records, more moddern reggae and fiercely rasta people like Sizzla—was what allowed me to ask those deep questions about myself. I mean, I’m not so much—my mum’s got blonde hair and blue eyes, but my dad’s a Jamaican from Saint Anne’s. But for me, music was always about how to help people think for themselves, even if it’s just for a brief moment. That’s why I continue to do it.

VG: Music can be liberation—it was very liberating for me to start doing music. It’s different from my default mode, which is just sitting at home, alone, writing. It’s so great because you get to be with people and have different families, little human tribes—like the one I had with the Flying Lizards in Brixton. Well, I don’t really believe in tribalism, actually. But at the same time, I think I’ll always be a North-West London girl.

M: It’s the same for me! Wherever I go, I’ll always have a South Londoner mentality. I will always sound like a South Londoner as well. Going to other parts of London doesn’t feel the same—North, West and East London are all different from South London.

VG: They’re changing so much. My East London is not the East London now. When I left, it was all about West London, where I’d moved to from North-West London. Then, what was West London became East London. And then, suddenly, what was East London became Hastings! Am I right, Mala?

M: Hah, to be honest with you, I’m not sure. I didn’t travel around London so much as a kid.

VG: One never had to. But now they do! It’s almost like you’d have to write a book about the social moraes and subtle distinctions between different parts of London. It’s also the architecture that defines it, as well as the acess to the tube.

M: We was never connected to the tube!

VG: That’s the dirty little secret underpinning the mentality and the jokey snobberies that people have. Coming from North London, we had the Northern Line, so Baker Street and the Oxford Circus and all of that were only a short bus ride. I spent a brief period of time living in Battersy, and that was hard for me.

M: Such a colorful life you’ve had. It’s really amazing listening to these things, and especially since I learned about you. How have you found time to do all of these things?

VG: Well, that’s very nice. I can only say one thing: I’ve got to earn a living.

Published July 11, 2016.