“We haven’t noticed that we are as gods”: Hans Ulrich Obrist in conversation with Stewart Brand

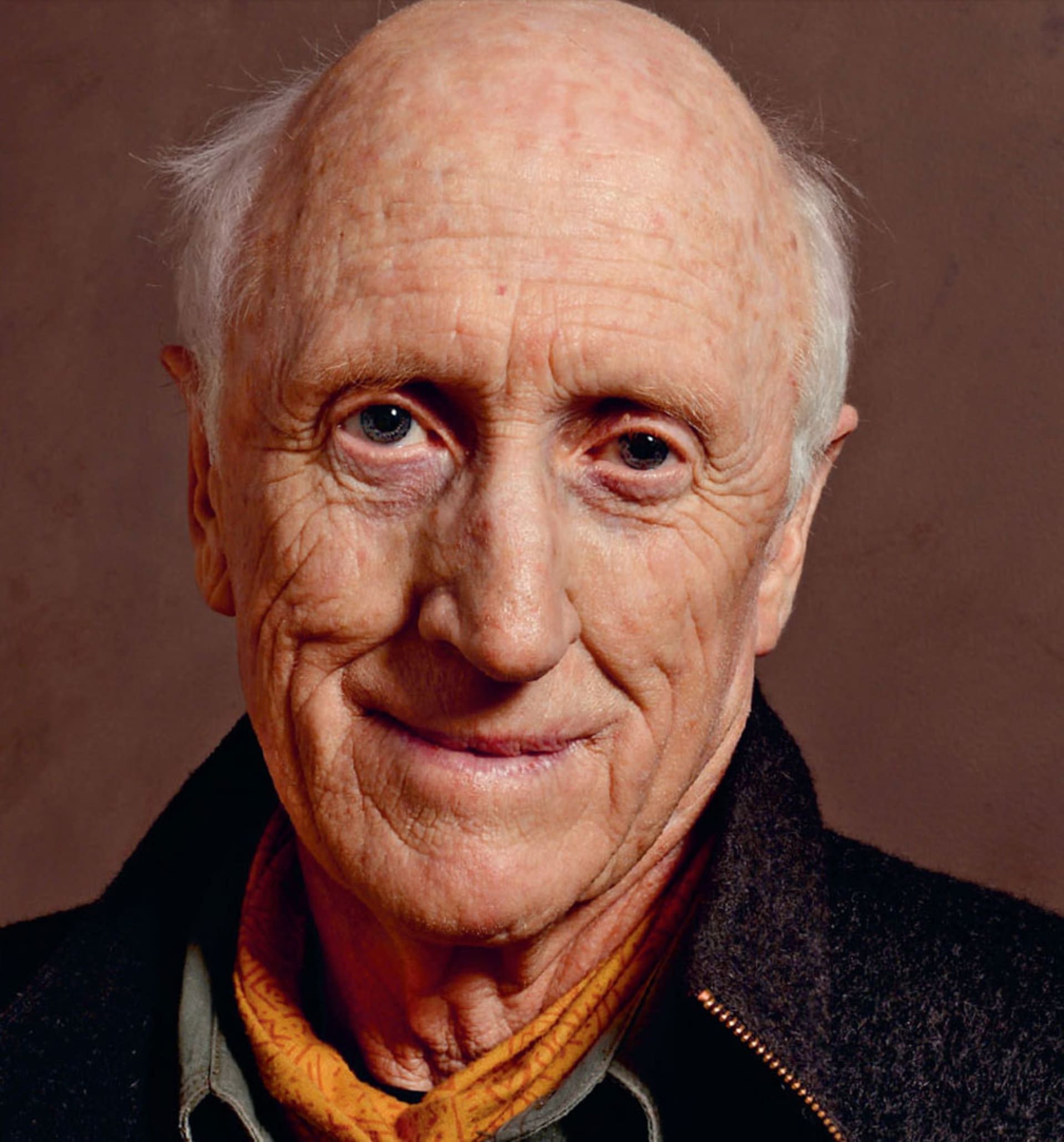

In this piece taken from our new Summer, 2013 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine, the curator and co-director of London’s Serpentine Gallery meets the esteemed writer, who conceived of and edited the original Whole Earth Catalog, on the occasion of the Whole Earth exhibition at Haus der Kulturen der Welt. (Above: Stewart Brand photographed by Larry Busacca, courtesy of Getty Images 2013)

Stewart Brand conceived the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968 as a collection of tools, tips and accessories to help America’s burgeoning hippie culture and alternative living communities change the world by understanding better how to survive outside of its conventions. Appropriating the font and concept from the then pre-yuppified L.L. Bean mail order catalogue, Brand’s vision of the objects necessary for self-sustainability included everything from special-purpose utensils, gardening tools and welding equipment to books on Eastern philosophy, early synthesizers and personal computers. The products were organized under categories such as “Understanding Whole Systems”, “Communications”, “Shelter and Land Use” and “Nomadics”, thereby conceptually maintaining a connection between the utopian and practical. Over the past decade, Brand’s visionary status has been cemented amongst the TED cognoscenti, with no less than Steve Jobs describing Whole Earth in 2005 as a farsighted nexus of thought not unlike that of a Google search engine. Today, the catalogue is also experiencing a period of fawning reassessment within the art world, and has become the focus of major exhibitions from New York to Berlin. In the current issue of Electronic Beats Magazine, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist spoke with Brand about the history of Whole Earth and its legacy in the Internet age.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: When one reads about your work, it seems as if you’ve experienced a chain-reaction of epiphanies throughout your career.

Stewart Brand: That’s sort of true, yes.

HUO: What was the first?

SB: I organized a rock and light show called the Trips Festival in 1966, because I realized that Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters wouldn’t be able to pull it off by themselves! Until then, I’d gone along with how they were organizing the event, but then I picked up the phone and started making the public event happen and it turned out to be easy and inexpensive and to have a lot of influence. That epiphany led to the epiphany that it was easy to make a difference in the world.

HUO: So the Trips Festival showed you that one can change the world?

SB: Yes, that it was easy!

HUO: That was a legendary festival, with one of the Grateful Dead’s first performances, and the LSD parties called Acid Tests, described by Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. It seemed to be a crystallization of the hippie movement.

SB: Nobody knew there were 10,000 hippies—everybody thought there were just a few thousand. On one weekend, we had this huge throbbing crowd of people and it was news to us, just like it was news to them. That’s when Haight-Ashbury was born: people realized that the hippie movement was large, powerful and fun. And then the next epiphany came with the realization that a photograph of the Earth from space would change everything. That was a classic LSD trip. I just printed buttons that said: ‘Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?’ and sold them for twenty-five cents.

HUO: You waged a campaign to make NASA’s image of the Earth available as a powerful symbol.

SB: It was a campaign in the sense that I was a guy with a sandwich board in a top hat standing outside several different universities. It was definitely a one-man campaign.

HUO: And that led to a national Earth Day. It showed, as you’ve said, that the Earth is a “jewel-like icon amongst a featureless black vacuum”. You often talk about the idea of auto-symbiosis and our connection to nature. Did this stem from that early experience?

SB: Yes. Just out of college, a set of realizations were coming into place: what I wanted to be and what I wanted to do and what I wanted to care about.

HUO: And who were your heroes at that time? Because you had so many different facets at the beginning of your work: you studied biology, then you studied photography, then you mounted activist campaigns, then you organized the Trips Festival—all of which is pre-Whole Earth Catalog. Then you assisted the electronic engineer Douglas Engelbart with this incredible presentation of revolu-tionary computer technologies.

SB: “The Mother of All Demos”, yes. In college, my hero was Ed Ricketts, a marine biologist in Monterey, whom John Steinbeck wrote about in his novels, Sweet Thursday and Cannery Row. Ricketts was a classic, bohemian-living, free-loving biologist, and I picked up on him in prep school. I went to California looking to be him.

HUO: Was this conference with Douglas Engelbart the beginning of your connection with technology?

SB: No. When I got out of the Army, in 1962, for some reason I was given a tour in Stanford University, where I’d been a student, of the computation center, and in the back room of the computation center, some guys were playing Spacewar!, which had just been invented at the MIT. What I saw was a window into another world: it was like when I first saw American Indians . . . just another world. And it gave me a sense, at that time, that computers were going to be of the essence, and so I carried computer stuff from early on in the Whole Earth Catalog, and when I stopped the Catalog in 1972, I finally wrote an article for Rolling Stone magazine about hackers, who had begun serious computer hacking in 1961 at MIT. I was told, “Well, we’ve got a scoop. This is going to become a standard newspaper story about what you call these ‘computer hackers’.” But there was no further news about hackers for another ten years, until Steven Levy’s book [Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution (1984)].

HUO: Amazing. Did you also have heroes in art or photography?

SB: When I got out of Stanford in 1960 and was on my way to serve in the Army, these beautiful books with lots of photographs started coming out and the “exhibit” format book was invented. I was becoming a professional photographer at that time, and I had a sense that I was on the right track. Robert Frank’s book The Americans was revelatory. Later, I got to know Frank as a very good friend in Canada. I bought property near his in Nova Scotia just to get to know him, but by that time he was no longer doing any photography. But he did come and shoot a film of an event I organized called “Life After Earth”. The event was amazing, and Robert filmed it … a very touching film.

HUO: And that’s a dialogue that continues?

SB: No, I’d love to see what Robert is up to. But there’s a long distance between California and New York, and you see it played out in many things. The clearest case, which I didn’t understand at the time, was that Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters were doing one thing on the West Coast, while Lou Reed, Andy Warhol and the Factory were doing something almost identi cal on the East Coast, but there was no linkage between them. It wasn’t until I got to know Lou Reed nine years later that I realized Andy did a better job than Kesey did on making radically creative stuff happen. We had the Grateful Dead, and he had the Velvet Underground. Both pretty good. The major linkage in those days between the East and the West Coast was Allen Ginsberg.

HUO: He traveled all the time.

SB: Allen traveled all the time. He connected the New York Beats with the California Beats: Michael McClure, Gary Snyder … Neal Cassady was with Kesey by then, so I got to know Allen through the Pranksters.

HUO: To come back to your work, in 1968 there was the epiphany of Whole Earth Catalog, which is a major invention of the twentieth century. I visit artists in the US all the time, from Vito Acconci to Bill Levi, and so often they have the catalogue in their studio. It’s so important for intellectuals. Do you remember when you had the idea?

SB: Yes. We’d just buried my father, who died at sixty-four in Illinois; I was on a plane going back to California. All the years I was growing up, my parents had been investing money in my name, and so there was this body of money that I supposedly owned but which I’d never had anything to do with. I figured: “Well, now I have to actually take responsibility for this money and do something with it. What should I do?” On the plane, I pretty much came up with the idea of Whole Earth. It’s called Whole Earth, but it was just access to tools: a truck store and catalogue. The truck store was inspired by the various communes that my friends were starting. I’d been on a couple of them and helped out, and they’d been started by liberal-arts college students who didn’t know how to do anything. They were busily trying to reinvent civilization from scratch without knowing how to do scratch. I had a pretty clear idea that I could acquire the tools that I needed. I had a science education; I knew how to make a refrigerator work. The idea was that there was going to be this truck that would travel around with these tools that would make it possible for the communes to create their own mini-civilizations, and there would also be a mail-order catalogue, which in my mind was based on a hunting and fishing catalogue called L.L. Bean. My father was a catalogue fanatic and so I knew that catalogue well.

HUO: So L.L. Bean was your inspiration?

SB: Yes. The typeface I used on the cover, the Windsor typeface, was a copy of the L.L. Bean font. I borrowed everything. I wrote that down right away because when you have an idea, you’ve got about five minutes to act on it before it disappears. So I wrote the idea down, a page or so, on my notebook, and then I played it out. I did the truck store first and found out that the communes desperately needed the information, but they didn’t have any money. I drove with my wife to these places, it took a long time to get there. Then when we got there, we were welcomed but they couldn’t afford to buy anything. So that wasn’t a commercial event, but the catalogue turned out to be a commercial event. So, of my parents’ money, I’d probably invested 10,000 dollars before it started coming back.

HUO: You did the catalogue’s layout yourself, and it was a unusual, oversized format. What was the inspiration behind that?

SB: Well, I’d studied design, both at Stanford and then afterwards at San Francisco Institute. Then I worked in Gordon Ashby’s design shop. He was a protégé of Charles Eames, who did the Mathematica exhibition. So the Eames-style design was something I was familiar with. There was a bunch of things that I wanted to do that were different in the Whole Earth Catalog. Design at that time was very much about the idea of white space: you’d have a lot of white space and some perfectly designed logo, rendered with graceful stylishness, and it might have some information and it might not. It was supposed to be beautiful. I wanted to totally flip that. I’d have a publication that had no white space at all. It was just crammed with information, all of which was useful. So I just clipped material out of all the books and catalogues and pasted it. With the IBM electric typewriter, which was the first kind of desktop typesetting machine and with a device that made sort of instant halftones, the technology made it very easy to do self-publishing. I couldn’t imagine any other way to do it.

HUO: Can you tell me about the text printed at the front of the catalogue under “Purpose”? It starts: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.”

SB: Yeah, that was another theft. I stole that from an anthropologist whose name and whose book I now forget, who said that humans were attaining powers that the Greek gods would have envied. Jesus was tempted by the devil who said “You can be as a God,” and Jesus said “No thanks.” But the rest of us all said: “Yes, thanks very much.” But we haven’t noticed that we are as gods, and that’s why we’re still crappy at it; we’re still trying to flip that. The flip is: take that as good news instead of bad news, and then act on it. We’re still getting good at that, whereas God isn’t.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, photographed at London’s Serpentine Gallery by Max Dax

HUO: This idea of the Whole Earth Catalog involves an encyclopedic approach. How did you go about the data collection?

SB: It turned out you could pretend to be a bookstore, which I did, and then you could buy books at a retailer’s discount. So I was able to buy large quantities of books, and that was the research, plus talking to people, wandering around.

HUO: In the nineties I curated an exhibition called Do It, which is still touring. It’s about the idea of not having objects in an exhibition, but recipes, instructions, how to manually do it yourself. It’s an art exhibition where everybody can do it. And during my research I found out a lot about the late sixties DIY culture. Was the Whole Earth Catalog connected in any way to this “DIY” moment—to Jerry Rubin or to an art movement like Fluxus?

SB: No connections to Rubin. I never met him and never liked him. Abbie Hoffman was a friend whom I liked a lot and I really miss. But before both of those guys was Paul Krassner’s The Realist magazine, and that was a model for the Whole Earth Catalog. Paul of course wrote most of The Realist, and his by-line was usually just “PK”, so my by-line in the Whole Earth Catalog was “SB”. Do-it-yourself, in my world, was something that middle-class people did in their garages, and us artists and college-educated people looked down from a great height on people who did things in their garages! That was “popular mechanics”, a disregarded world. So I was just basically taking DIY a little bit upscale, or intellectualizing it, or something like that. But I had no connection with it. The East Coast also had John Brockman, Steve Durkee . . . we were collaborative, cooperative artists and engi- neers, and we were sort of in the milieu of John Cage and all that. But really that’s the extent of the East Coast in the very early sixties.

HUO: How did your dialogue with John Brockman start?

SB: We were both at a conference. There was John, Norman O. Brown, and some other people, and John was going on about dolphins. He gave me a page about the book he’d like to do about dolphins. He sold it very quickly, for very good money. It must have been 1967 or something like that, and when I was planning the last Whole Earth Catalog, in 1971 – 72, Brockman went to the New York publishers and got us a great contract with Random House, which was huge. And then it became a bestseller, the first trade paper- back. So by then, Brockman was my agent and he got me in.

HUO: What I find so interesting is that despite having sold millions of books with the Whole Earth Catalog, it’s clear from the beginning you wanted not just to preach to the converted, but rather to go out to the world. That also became clear when in the seventies you went into politics and became advisor to Jerry Brown, the Governor of California. How do you feel about this whole idea of science for all, art for all, going beyond a limited, specialized audience to a more general one?

SB: Both groups of people who made up the counter-culture in the sixties—which was the New Left and Abbie Hoffman on the one hand and the psychedelic crowd around Ken Kesey on the other—assumed a national audience. Perhaps it was because we’d grown up on television. We called press conferences and people would come; we’d have the expectation that there was going to be a national audience and there was. So it was an assumption at that time that was very well rewarded. People went out, did communes for a while, got really bored, came back to town, tried to do political activism. They wanted to get into local politics so they got onto the school boards and even ran for local office. And for me, working with the State Governor was kind of a smaller thing than the national audience we’d all got- ten used to. But that’s where the national effectiveness was, of course. The rest was just noise.

HUO: Yeah. Jerry Brown was kind of exceptional.

SB: Very exceptional. Still is.

HUO: It’s been remarked that the Whole Earth Catalog was like an early version of Google, and during the 1980s you invented the online community THE WELL, which was a kind of prototype for today’s online publications. What was the epiphany of the WELL? SB: There were a lot of little online communities then. And there were some medium-sized ones. I’d been part of a medium-sized one called The Eyes at New Jersey Institute of Technology. I saw some bulletin boards, which were these local, online group discussion things, run out of someone’s basement. And these were starting to operate at a national scale, like with CompuServe. To participate would be very expensive: they were like sixty dollars an hour. And so what I had in mind was brilliant. Basically hire a service. This company, Netty, would put up the money for us to do a Whole Earth Catalog online. And I was pretty sure that that wouldn’t fly, but that a form of discussion online would fly, because I’d seen versions of that with The Eyes. So all I was doing was taking what I’d learnt from The Eyes, which was that it should be cheap but not free —it was two dollars an hour, eighty dollars a month. And there should be no anonymity. Not as good as Facebook’s lack of anonymity. I should have done that. But anyway people changed their “handle” all the time, what they wanted to be called, but the real name was available on there. And there was instant access: nobody had to sign in, and nothing physical happened. People got on, used their credit-card number and they were instantly in, even before we’d cleared their card. So: instant gratification, low cost and free subscriptions to journalists. And you owned your own words, which was my attempt to work around us being liable for the things that people say to each other. I said “Look, all we have is a phone company and people insult each other on the phone, nobody sues AT&T. We’ve got to have it understood that nobody sues us; you own your own words.” We knew enough hackers thanks to the Hackers’ Conference to help to write the manual and improve this very bad code we were working with, called “People’s Spam”. So it was kind of a boot-strap operation, a combination of writers from the magazine I edited, CoEvolution Quarterly, and other journalists, plus programming skills from the hackers. That combination gave it an interesting voice that then drew other people in. It was a self-enforcing community. I wouldn’t say that was an epiphany, but just a set of designed decisions.

HUO: When I started out as a curator, in the late 1980s, it was an activity exclusively of the art world, but now, on the Internet, it’s become the big buzzword. Do you see yourself as a curator of knowledge? How do you view this notion of curating and selecting, which is becoming so important in our current world?

SB: I think it’s been a very useful word. Chris Anderson uses it with the TED conferences. He’s basically a curator of that body of speakers; it’s a very good use of the term. I’m curating a lecture series, but to me it’s exactly what I did as editor of the CoEvolution Quarterly—basically bringing interesting people and interesting subjects together. Curating is assembling, it’s letting other people do most of the work. It’s a very lazy, therefore good, way to influence the world! It’s a question of intelligent collection and then of intelligent display. And it’s tremendously educational for the curator. The curator has more fun than anybody. I expect you experience this, because you get to learn about subject after subject after subject, person after person. Some curators specialize and other curators—I guess you and I are examples— tend to generalize; generalization is a form of specialization: that’s what we do. Like everything else, it’s been democratized by the Net, so, in one sense, everybody is curating. If you’re writing a blog, it’s curating. Blog items now all have to have an image, so people are getting literate in images that work, and you can have a whole entity like iStock Photo that just sells amateur images for a couple of dollars that work very well. So we’re becoming editors and curators, and those two are blending online. Lots of people are organizing online conferences. It’s much easier to do that than real-life physical conferences, as in the old days. Curating has become a generalized, democratized skill.

HUO: Have you ever used the medium of the exhibition?

SB: One of my first jobs was as an exhibition designer. I mentioned Gordon Ashby, who had been Eames’ protégé. I was hired by him shortly after the Army to be the researcher for an exhibition called Astronomia, which was like Eames’s Mathematica. Astronomia was funded by IBM to be at the Hayden planetarium in New York’s Museum of Natural History. And so I got to study the history of astronomy and to figure out what objects from that history would be good artifacts to act as a series of windows on the astronomical events, mostly in Europe, that were going on during the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I got the glass plates that Fraunhofer made, which started to give us the knowledge of what stars were made of. What I couldn’t get was Galileo’s telescope, so we just reproduced it. One of our first exhibits was the constellation Orion: three stars—the belt, the sword. It sort of looks like a guy with a belt from the front, but of course, from the side it doesn’t. So we made a box that you looked at from one end, and you saw Orion represented by a set of little LED- type lights, arrayed in different brightnesses. Constellations are just a matter of perspective, and space is primarily a volume, and a surface. This was very high- level exhibition design that we did. Astronomia stayed at the planetarium for twenty years or something like that. Then I was asked to work with four new museums.

HUO: Do you have any projects too big to be realized—dreams, utopias?

SB: I like the idea of space colonies, and that hasn’t happened yet. Not that I’m ready to go out and try to make that happen. I have friends who are doing that, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson. One of the largest things I want to see happen is various geo-engineering schemes; we need to go forward on that scale, but it won’t be me doing it.

HUO: And what would be your advice to a young artist or researcher?

SB: The best thing I did as a college student was major in biology, and when I hear young people ask: “I can’t know what I’m going to do in life, so what should I study?”, basically I say, “Science is your first thing. Whether or not you become a scientist, you’ll use that way of understanding, that way of checking your own thinking.” That’s a much more rewarding and adaptive way to live intel- lectually than the others. I wish I had had more anthropology. I wish I’d gotten theatre skills. I got design skills, photography skills, and command skills in the army. Acquiring a whole basket of skills and then getting in the habit of acquiring more of them is much easier and more common today than yesterday. It’s not the case in Europe, but Americans are monolingual, and so any American who doesn’t at least know Spanish is going to be severely limited. And, you know, I even studied a bit of German at Stanford just because I wanted to read Goethe.

HUO: I’m working on a list where I ask artists and writers to give a sentence about the future. What would be your definition of the future?

SB: The future is 10,000 years long, and with that perspective, a concept like “Seize the century” sort of makes sense. If you think your life is eighty years long, then “Seize the day” is the right advice. We’ve “centuryized” climate change: it’s not going to be fixed in a year, it’s not going to be fixed in a decade, it’s not going to be fixed in two decades. We may get ahead of it in a century, but it’s a century- scale problem and that’s why The Long Now Foundation exists. And it’s why we’re going to do a 10,000- year clock at the Smithsonian.

HUO: So it’s about long-distance running, not sprinting.

SB: Oh yes, very long distance running. ~

Read Heatsick’s recommendation of the Whole Earth Catalog here.

Published July 01, 2013.