Gilles Peterson and Motor City Drum Ensemble in Conversation

Electronic music production in Poland may be on the rise thanks to producers like the RSS B0YS, but for about 100 years the country has been steeped in jazz. Under Soviet rule in the 1940s, bans on cultural production meant the burgeoning jazz scene ducked underground, and jazz didn’t make its way out of the catacombs until after Stalin’s death nearly a decade later. Behind the Iron Curtain, jazz clubs and festivals began to blossom and foreign musicians found their way in via radio waves, and the scene became more robust and stable over the subsequent decades.

A few hours before our latest EB Festival in Warsaw, we sat down with BBC Radio 6 selector Gilles Peterson and German DJ/producer Motor City Drum Ensemble, two dedicated record collectors known for both their deep affinity for, and knowledge of, jazz. With the Palace of Culture and Science just across the road, the pair speculated about the rise of free jazz as a reaction to repressive political climates in Eastern Europe, the deterioration of politics in club culture, and how “kids today” are tapping into avant-garde jazz legacies via Flying Lotus and the Brainfeeder tribe.

Motor City Drum Ensemble: I think the last time we saw each other was at Southport Airport.

Gilles Peterson: It’s funny; I bump into so many DJs at airports. It’s kind of the meeting point. Now we’re meeting in Warsaw, where there’s a long history of jazz. All pioneers in the music scene are jazz heads, like Carl Cox or any of those guys who have lasted.

MCDE: It’s the tree, the roots. We all go back to jazz.

GP: My brother studied in Switzerland when I was 15 or 16, and I used to go visit him. I’d hitchhike from Lausanne to the Montreaux Jazz Festival. I remember seeing [Polish jazz musician] Michał Urbaniak and [Polish jazz vocalist] Urszula Dudziak there, which were probably my first experiences of Russian-influenced jazz. They were my first two Polish stars. One of the records I’ve got here is a record by Urszula Dudziak, and there’s a track called “Papaya” on it that’s a disco jazz jam; it’s wicked. And all the Michał Urbaniak stuff are very fucked up, basically, and very techno.

MCDE: For me, growing up in Southern rural Germany, I was exposed to a lot of American jazz and German jazz, but I couldn’t really find this kind of stuff. Because I put out my first record when I was 16, I got to travel to Croatia. I went to a record store there and they had records that I’d never seen before, and they were all on the same label. I was like “What the fuck is this label?” It seemed like totally free jazz and it opened up a whole new cosmos for me. I found tons of fusion jazz from former Soviet countries.

GP: Whether you go to Norway or Finland or France or anywhere, they all have little inner jazz places. They all have their scene, and I find that the further east you go, the more avant-garde it gets, the freer it gets.

MCDE: I think the Eastern European musicians became freer because they were restricted, and there was no possibility for them to be political in their lyrics, so they had to have some kind of way to put out their anger without saying real words.

GP: I think that’s a very good theory. I’m going to use that. Yet, I think that music in general has become much less political. It’s become much less cool to be political. The peak of political music for me was punk, which was a subversive reaction to Thatcherism in the UK. If you were a band you had to have a political point of view, but nowadays people avoid it. It’s gotten more existential, especially with dance music. What’s political about going to Berghain? Everyone’s just kind of been taking ecstasy and it’s neutralized everyone’s energy somehow. That’s the danger of dance music: It’s all a bit too self…

MCDE: …centered.

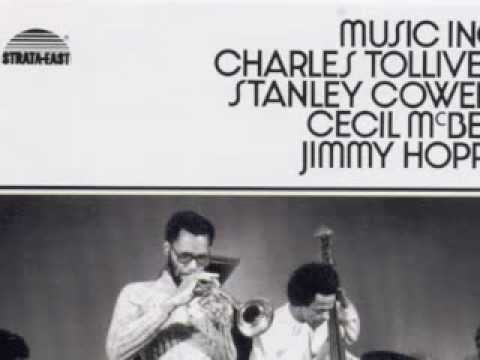

GP: Yeah. And I think a lot of the political jazz happened before the 1970s. I’ve been doing a lot of work recently with a guy called Charles Tolliver, who had a label called Strata-East, which was closely associated with people like Gil Scott-Heron and The Last Poets and was very much about representing black culture and giving it a platform. I also liked the whole Jazzanova thing.

MCDE: I’ve got a funny story about them. When I first went to Warsaw, I went to a record store with a checklist of stuff I wanted to buy. I asked for some of it and the clerk said, “Sorry, we’re out because week ago some guy from Berlin bought a whole stack. They go by the name of Jazzanova.”

GP: For me, Jazzanova was very interesting as a concept and as an ideology. They were very important, not just in terms of how they approach their business, but also in how they provided a basis for German electronic music to come through. I don’t think they get enough credit for that. You’ve got Dixon and Âme and all these people, they all kind of got the boost from Jazzanova.

MCDE: I feel that the whole intellectualism in music has been a bit watered down. With a lot of the records we’ve discussed so far, you really have to listen to the whole side to get what they’re actually about. Free jazz is about listening to a 20-minute piece with two particular minutes that really speak to you. Kids today don’t have patience anymore; they have mobiles and constantly do ten things at once, and this way we keep them from actually finding what music’s truly about, or what they’re about. Maybe that’s why political messages are so few and far between in music these days.

Photos by Jannik Schaefer.

Photos by Jannik Schaefer.

GP: As a broadcaster, I think radio a really beautiful platform to subliminally put messages out there in terms of your vision and political perspective. However, I got into a lot of trouble with politics and music; I got fired from a radio station called Jazz FM during the first Gulf War because I told everyone to go to the peace march. I brought politics and music together, but it was really dangerous for me. I don’t know how you can educate people through DJing, because when people go to clubs, they want to have a good time, to party, to fuck someone, to get high or just dance. It’s a selfish thing. As a DJ, the moment you go in there like, “I want to educate,” you’re fucked. You have to be much more subtle than that.

MCDE: I have to agree with you, but in the last couple of years, you can sense that a new generation is sick of being spoon-fed the same boring music. These days, I get the biggest peaks playing super obscure records. Young people want to hear something new and discover things they can’t find on the Internet that everyone has on their iPhone.

GP: Yeah, the youth is tired of being sold bullshit for money. Ibiza is a good example; I don’t go there anymore. Maybe that’s why an incredible musician like Flying Lotus has become so popular. He was working with Austin Peralta, who was a proper jazz musician. He has Kamasi Washington on Brainfeeder, which is a powerful label and part of a powerful scene. My kids are 16, and they love Flying Lotus. Yesterday morning they were listening to Thundercat. That’s powerful because those guys are the natural link to free jazz, to George Duke and to fusion and all of that.

MCDE: I agree about Flying Lotus, and I was also really happy to see D’Angelo make a comeback. I regained my trust in good music. That has been the biggest eye-opener for me this year: to see that something like this is possible in mainstream music. The thing is that contemporary jazz doesn’t get recognized very much. You play some contemporary stuff on your radio show, but if we’re comparing sales from a beautifully crafted gatefold of modern jazz record to your average 12” of house, it’s crazy. Nobody buys modern jazz, even though it might be incredible.

Interview and photography by Matthias Klein and Jannik Schaefer.

Published March 30, 2015.