Who Really Benefits From Discogs Scalping?

I just sold my copy of a White Material EP for €50. Mine was one of 300 hand-stamped 12”s that the White Material label distributed in a nondescript paper sleeve, and I bought it for $10, and now I’m going to make a 500% profit re-selling it on Discogs. Although I really like the record, I don’t really think any vinyl is worth that much money, and I seized the opportunity to sell it for 50 bucks because that was the going rate for the record on Discogs—I wouldn’t have gotten rid of it otherwise. But someone had to be the first person to ask for €50 in exchange for it, and that person is a son of a bitch.

There are only five White Material 12″s in circulation, and most of them were at one time or another worth more than €40 on Discogs, despite their humble packaging and recent release dates. So far, they’ve only repressed the inaugural record, although they told me they’re working on repressing the others and perhaps offering digital releases. Nevertheless, the high cost of White Material items have not gone unprotested on Discogs and in the press; irate Discogs users debated the label’s “hype,” begged for represses, and bemoaned “price gougers” who are “taking the absolute piss” or advertise multiple mint-condition copies of in-demand records that they clearly purchased to resell, not to play or love them. Meanwhile, the most prominent mentions of White Material in the media have touched on the controversy over the record prices, from little blurbs in Mixmag to personal indictments from the villainous blogger Ratchett Traxx, to label features on RA and Spin and articles about expensive new records on THUMP. You get the picture.

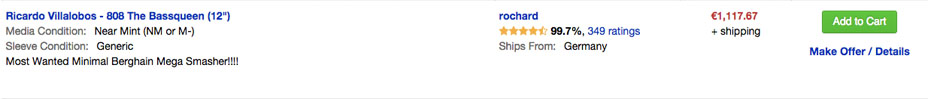

White Material has become a whipping boy and paragon of the phenomenon by which new records are resold for unreasonably high sums on the Marketplace, which is colloquially known as Discogs scalping, a phrase that connotes manipulation and cunning. Other vinyl-only labels have experienced similar cycles of ravenous interest and bitter backlash. Berceuse Heroique’s repress of a Loefah 12″ in December 2014 sold out in minutes and immediately appeared on Discogs with a price upwards of €230, which inspired incredulous Reddit threads. Commenters on the Discogs page for Bandulu Records’ fifth release named specific sellers for lying about having a copy or charging too much for one.

The phenomenon has become an epidemic and a fact of life for vinyl collectors in the age of Discogs, the contemporary behemoth in the online market for physical records. A whole subphylum of nerdy jokes have manifested in the form of cheeky fake listings that poke fun at inflated prices, and certain sellers have become infamous for their inconceivable rates, like Tanmushimushi, a now-defunct user who has become the subject of incredulous and outraged threads on Twitter, DJHistory, Reddit, Dubstepforum, Discogs, and other message boards.

The online rates have even crossed over into brick and mortar shops. The Record Loft in Berlin bases its prices on what’s listed on Discogs, so shoppers are subject to the website’s rates even when they’re buying from an IRL retailer.

“It’s a common thing to do for almost all record shops I know,” said Record Loft founder Christian Pannenborg. “Nobody speaks about Discogs as a price guide, but all do it. It’s easy to use and when you’re pricing tons of records, you need to be fast. In our case, I wanted to put this process into public—maybe it kills some of the mysticism [around the process]. I wanted to be transparent. I wanted to give the customer the downright baseline so that he knows he can’t get it cheaper than here.”

The esoteric nature of record pricing inevitably makes collectors grumpy, but I’m not sure who’s to blame for the unfair prices. I see buyers accuse labels like White Material of pressing small quantities or hoarding the stock in order to limit the supply and thereby manufacture rabid desire for a scarce product and increase the amount of buzz around a release. They also resent the sellers who take advantage of hype by demanding exorbitant sums for rare 12″s, especially those who buy copies of in-demand records with the intent to make a profit rather than play or listen to them. Artists, in turn, sometimes take umbrage with scalpers for using their talent and hard work in order to make a quick buck. It seems frustrating for some to imagine their records going to greedy amateur entrepreneurs who intend to rip off the fans who actually like their music and want to play it. And I bet it’s even more infuriating for the artists to know that the sellers are making more cash off their labor than they did.

Yet despite their high profile and integral role in the record-buying community, “scalpers” have never weighed in publicly on their motives or operations, so I contacted some until I found a few who were willing to chat. According to a seller called shaun31674, users often send him nasty messages who “assume that I’m just buying the records so that I can jack up the prices later on Discogs.” Until I reached out to him, he had never received a message asking for his side of the story, which turned out to be pretty nuts.

“I started selling records [on Discogs] because I needed the money, plain and simple,” he explained. “I was arrested for trafficking cocaine, and my money was confiscated by the police and I was evicted from my apartment. My father had also recently committed suicide and I was dealing with depression and anxiety disorders, along with a drug addiction. I was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, and when I got out, I needed some money for living expenses, lawyer fees, etc., so I began selling some of my records on Discogs.

“Most of my records are from my collection and I set the prices to what other people are selling them for. The reason I have so many records is because you make good money selling drugs, so you can buy pretty much whatever you want, and in a five-month span I bought about 300 records. A lot of the records I don’t even want to sell, but I’ve been forced to because of some of the hardships I am currently enduring. I do not have a job because I have been deemed unfit to work by my doctor due complications with my disorders. Besides disability welfare, this is currently the only other income I have.”

I don’t know if shaun31674’s tale is made up and I couldn’t find a Canadian arrest record to corroborate it, but I’m not sure that its veracity really matters. It seems entirely possible and maybe even likely that the demonization of a Discogs scalper as a manipulative and opportunistic shark out to make a quick profit off someone else’s creative sweat is often unfair, and that the anonymity of the Internet makes it easy for people to assume the worst of others. After all, I bet dealing records isn’t nearly as lucrative as dealing drugs.

“This is a stupid and ridiculously time-consuming way to barely make a living,” wrote Occidental, a seller I contacted once a DJ friend of mine called him a scalper. “Instead of playing the stock market and making real money, I’m juggling just a few hundred dollars every month.”

Granted, Occidental’s motivations for hawking new 12″s at steep prices are more cutthroat than shaun31674. “It’s easy for kids to be rude when they’re writing anonymous messages with fake names,” said Occidental. “Someone might cite the ‘highest’ price in a record’s Discogs sales history and complain that my price is higher. I’m playing a market that moves forward. I keep my ears forward. The Game does not wait. Material lust is a bitch, and I understand the fetishist mindset. I understand the addiction.”

Despite Occidental’s dog-eat-dog outlook, I can understand that he’d rather make a little money doing something related to his passions than slaving away at a job that has nothing to do with them. His Discogs hustling is a way to make his obsessive record collecting habit profitable, which it needs to be if he wants to continue doing it.

“Flipping records is just a way to get over until I can earn money doing the things I love,” he wrote. He told me that he looks forward to the day when he can stop dealing records and focus on mastering 12”s—Occidental runs an engineering company of the same name—DJing, and producing tracks himself. He also runs a party in Colorado called DEEP CLUB, which he invited me several times while encouraging me to downplay his involvement with Discogs, because “the other things I do are SO MUCH MORE IMPORTANT” to him.

“Since I’m going to spend ridiculous amounts of my time listening to other producers’ music—because I’m obsessed—why not reconfigure part of my obsession to work for me?” he wrote. “At this level of commitment my work must yield an income. DJing, producing, and mastering—these are the more creative, more satisfying, and altruistic facets of my obsession: my love. When DJing pays and I get more mastering projects, I won’t care so much about selling records. And that will be beautiful.”

For Occidental, record selling is a means to make ends meet and sustain a passion that consumes a lot of his time, and the responsibility to press enough records so that the scarcity won’t artificially drive up prices lies with the record labels. Sometimes, he works out deals or trades directly with labels—although he wouldn’t say which ones—and often, owners reach out to ask him to stock their releases.

Still, it’s unlikely that every expensive new record label benefits greatly from Discogs scalping—and it’s even less likely that they all chose to press limited quantities to jack up their buzz, although some probably do.

“We had no idea,” explained DJ Richard of White Material, who also works at the Record Loft. “We thought that [300 copies of a record] was actually a lot. We thought we were going to be stuck with them forever. None of us had any clue how many copies other labels were pressing, because we had never worked at a label or for distribution or at a record shop, so it just seemed like that was a lot. We were really used to making tapes and stuff like that, or a CD-R, and those come in editions of 20 or 50.We were used to music being distributed on a much smaller scale.”

The assumption that labels limit the supply in order to engineer desire for scarce products pressing even 300 records is a big investment when the entrepreneurs don’t know if they’ll be able to sell them all, and when all the money for producing the records are paid for out of the artists’ own pocket, as is the case with White Material.

“Things didn’t even really pick up until the third record was already being pressed,” DJ Richard said. “That was when the first two sold out. So when we were pressing the third record, we were still in the mindset of the demand for the first two. It didn’t go insane on Discogs until after that. It was not intentional to press too few.”

So, the scalpers aren’t making much money, and neither are the record labels—but Discogs is. The site charges an 8 percent fee on all sales conducted on its servers, so the company gets more money if a given record sells for €50 than if it goes for €10.

Discogs founder Kevin Lewandowski declined to comment on how much money is exchanged on the marketplace every year. According to an article on BizJournals.com from early 2013, Discogs facilitated the sale of 12,000 music items per day, most of which were vinyl records, and raked in $1 million in annual revenue. In January 2015, Nielsen SoundScan reported that vinyl sales in 2014 increased 52% since 2013. An entry on Worthofweb, a site that claims to deliver an estimate of a site’s net worth based on its Alexa rank, lists Discogs at $82 million.

Actually, Lewandowski didn’t directly respond to any of my questions. We had originally scheduled a phone interview that I had to cancel, and so I opted for an email exchange instead. My first batch of questions contained 11 queries, and he returned with one response.

“My basic answer is it sucks what the scalpers are doing,” Kevin replied. “I don’t like it. But on the other hand this is a marketplace. Sellers are free to list for any price they want. And buyers are free to buy when the feel the price is right. It happens on eBay too. And if Discogs weren’t around, there would be some other marketplace where it would be happening.”

He didn’t reply to further inquiries about Discogs’ vested interest in driving up prices, so I’m left with that first response. We’ve been swindling one another and ripping each other off since the dawn of barter economics, and capitalism pits individuals against one another in an endless pursuit of trivial material rewards. If it weren’t happening on Discogs, it would happen somewhere else, like eBay or brick and mortar record stores, where it’s already an established practice. Of course, that’s exactly the justification that drives people to price records based on how high other sellers have listed it in the first place.

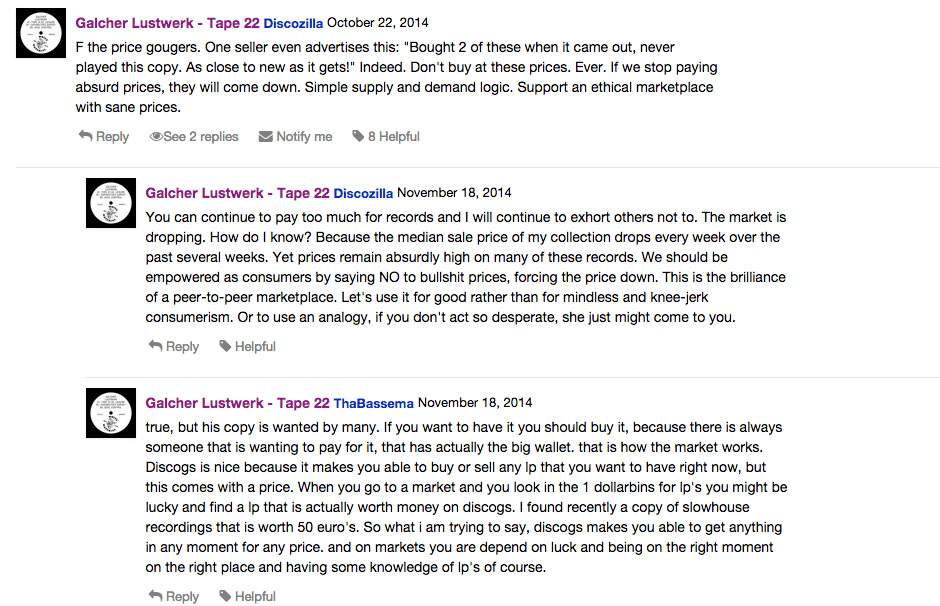

Discogs users do have some potential agency to undermine inflation. Sellers could choose to offer wares at “fair” prices, regardless of the going rate, and buyers could choose to boycott “unfair” prices.

“Don’t buy at these prices,” Discozilla pleaded on the WM003 entry in October 2014. “If we stop paying absurd prices, they will come down. Simple supply and demand logic. Support an ethical marketplace with sane prices.”

Unfortunately, it seems that rational supply and demand logic doesn’t determine the going rate for a White Material 12″, and it’s hard to tell exactly what forces govern record prices on the Marketplace. If supply and demand played the deciding role in that process, it would follow that the records with the lowest supply (WM02 and WM03, which haven’t been repressed yet) or the highest demand (WM03, which has the highest ratio of people who “want it” on Discogs versus those who reported having it) would be the most valuable White Material records. But WM03, which is both the label’s most rare and most sought-after 12″, was only the third most expensive when I looked in early February.

And that seems like one of the most maddening things about Discogs scalping: it illuminates how arbitrary record prices are, and maybe all prices of everything. They materialize from processes I’m not privy to and have little influence over, and then I have a choice between paying an unjust price or not having what I want. That’s a lose-lose situation.

As a record buyer, I’m at the mercy of record labels that press limited quantities of little plastic discs that I crave. I’m at the mercy of omniscient “laws” like supply and demand, and, perhaps most of all, I’m at the mercy of other record fiends who, like me, spend too much money on records and will seize any opportunity to recoup some of their losses or get a good deal. It’s another polymer in the grand history capitalism in which the blame for an injustice seems to spread in all directions but ultimately lies with an alienating and comprehensive system in which one person’s success rides on another’s loss and in which the responsibility for change lies with each individual to make ethical choices. Yet the “right” thing to do often feels totally ineffective at enacting change—my decision to sell that White Material record for €10 probably wouldn’t have convinced anyone else to do the same because “fairness” is irrational in a capitalist paradigm; it wouldn’t make sense to charge €10 when I could earn €50.

So I guess we all lose, except maybe for Discogs.

“I don’t want to give anybody the feeling of arriving home, looking into prices and feeling ripped off,” Pannenborg told me. “I don’t want to damage peoples’ relationship with music and vinyl and make them become jaded. On the other hand, if you need this particular record when it’s hype—well, then you need to pay the price for being late. There’s so much great music out there thats overlooked and super cheap, too. If you think you need the rarities than you’ve made your choice.”

Published March 27, 2015.