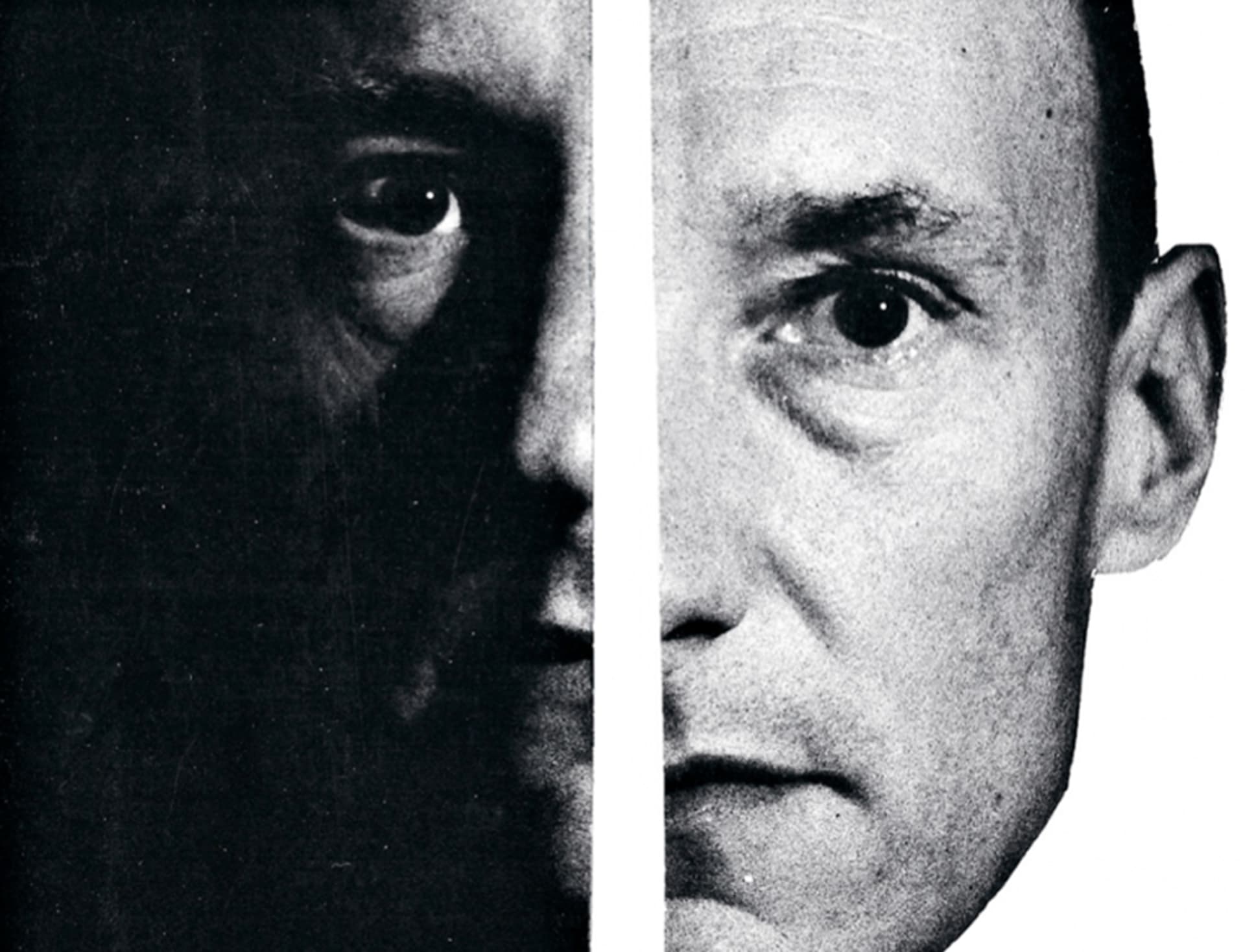

“A way to cut through the straitjacket of language”: The Art of William S. Burroughs

With the cut-up method, artist and writer William S. Burroughs hit upon, or should I say “rediscovered”, a compositional technique that was ahead of its time—a truly visionary anticipation of the way we now process information on a daily basis online. That is to say: cut-up was a different way of seeing. By slicing into messages of mass-dissemination from newspapers, film or audio-tape, mind-bending coincidences emerge that otherwise would have remained invisible. It’s a process that relies on healthy doses of serendipity and synchronicity, where a kind of magic occurs that releases its hidden powers in the shuffling of text or tape. It’s also fitting that it was originally visual artist Brion Gysin who “stumbled” upon this technique by accident in the Beat Hotel in Paris’ Latin Quarter in the late fifties, when he took a box-cutter to a stack of newspapers in the late fifties. Slicing up various sentences, Gysin immediately saw how one line of type, when unhinged from the rest of the text, would interact with other random lines in completely unpredictable ways. When he showed this phenomenon to Burroughs in Paris, Burroughs immediately began experimenting with it as a way to run interference against the world of oppressive communication he called “control.” You see, Burroughs believed that language and image were viral and that the mass-dissemination of information was part of an arch-conspiracy that restricted the full potential of the human mind. With cut-up, Burroughs found a means of escape; an antidote to the sickness of “control” messages that mutated their original content. If mass media already functioned as an enormous barrage of cut-up material, the cut-up method was a way for the artist to fight back using its same tactics.

Cut-ups, Cut-ins, Cut-outs: The Art of William S. Burroughs provides a good introduction to Burroughs’ and Gyson’s cut-up techniques, as well as its influence on a wide range of artists, from Paul McCartney to punk poet Kathy Acker. The book begins with an early conversation between Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso in 1961, where Burroughs famously proclaimed that “death is a gimmick” and that all political conflicts only serve to hide what’s really going on. From there, the book proceeds to highlight the extent to which cut-up was an actual mental survival strategy for Burroughs; a way to cut through the straitjacket of language. With an excellent selection of his work from the Barry Miles Archive and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others, Cut-ups provides an accurate portrayal of the cultural context in which Burroughs’ work was received. This is one of the book’s most important accomplishments.

The other would be its concise historical contextualization of cut-up as an artistic method. Brion Gysin once said that writing was fifty years behind painting and therefore something radical was needed to bring literature up-to-date. As the book explains, cut-up is more-or-less an extension of the collage—an art form that has been around since the nineteenth century and which reached its first peak with Dada. But as a technique, cut-up remained bound to the visual arts until Burroughs published his “Nova Trilogy”— The Ticket That Exploded, Nova Express and The Soft Machine. These books were essentially made up of the same content, just re- ordered and shuffled around. And even Burroughs’ most well known work, Naked Lunch, was assembled for publication in cut-up fashion. Interestingly, after Ginsberg persuaded Maurice Girodius of Olympia Press to publish it, he ended up with only a week to assemble the raw material. As a result, they employed a sort of “cut-up division of labor” with various people typing up different sections, which lent a more than a little bit of refreshing randomness to the whole editing process.

You often see this today in science fiction or in spy movies, like in the Mission Impossible series, where someone has a large database of bits of recorded speech that is used to create an artificial conversation by pulling someone else’s words out of context. But what these scenes really show us is that the single voice is really more of a composite of our social experiences; a multitude of voices speaking through us. While it may have seemed far-fetched back in the day, now, with our plethora of automated interactions, we have conversations with robots on a regular basis.

Published October 15, 2012.