A week in the life: 168 hrs Kraftwerk, NYC part 1

Photo: Max Dax

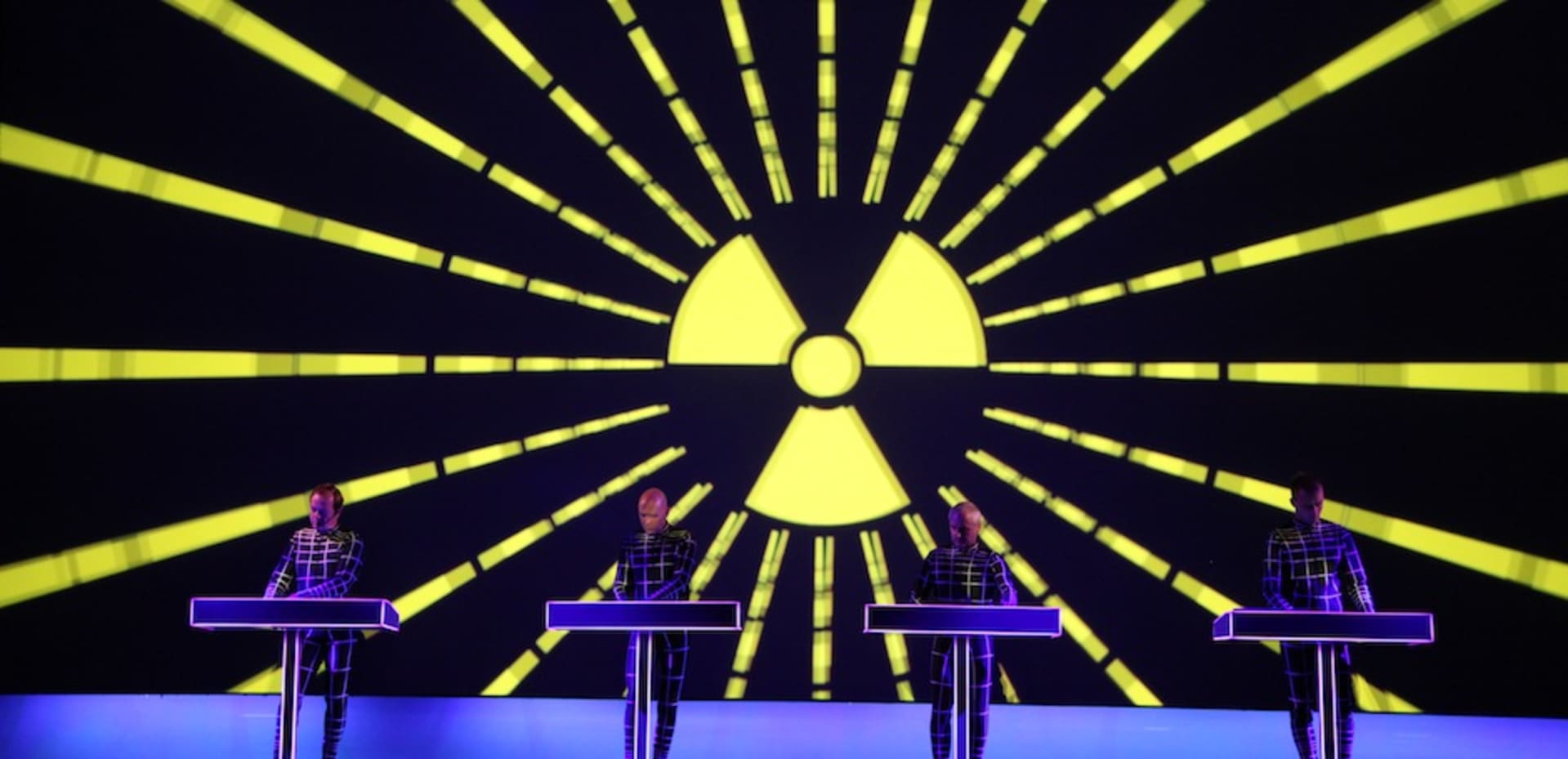

Few bands cast a shadow as long (or wide) as electronic pioneers Kraftwerk. The influence of the band’s trail-blazing retro-futurism, conceptual precision and electronic minimalism is difficult to overestimate, extending beyond numerous genres of electronic music into the broader realm of art and popular culture. And the art world seems to have caught on. This past April, New York City’s Museum of Modern Art presented Kraftwerk Retrospective 12345678, a series of eight sold-out 3-D concerts, one for each Kraftwerk album, beginning with 1974’s Autobahn and ending with 2003’s Tour de France Soundtracks. The result was an audiovisual tour de force that put the “werk” into Gesamtkunstwerk— with peerless kraft.

TUESDAY

Klaus Biesenbach, Director of MoMA Ps1 & Chief Curator At Large at the Museum of Modern Art

Photo: Luci Lux

Honestly, I don’t really know anything about the music world—I just know a lot of musicians. So when I first contacted Kraftwerk in 1998 for the Berlin Biennale, while I was working with Christoph Schlingensief, I had no idea what to expect. I think at the time, Kraftwerk were at a point in their career when they had yet to decide if they really wanted to commit to the art world. The thing is, 1998 was also the height of the Love Parade in Berlin, and the organizers also asked them to take part, which they didn’t do. But I think maybe they were scared off because we both asked at the same time. It took a while, but they answered our call in 2007. That’s when we first started putting this in the works.

What we’ve done in the MoMA atrium is pretty much recreate Kraftwerk’s Dusseldorf-based Kling Klang studio, down to very minute details. Attending every show and being so caught up in the process, I’ve experienced the retrospective in a very specific way: The first night I was completely exhilarated; the second night I was irritated by the rhythm and duration; the third night I was completely addicted. It was like being on a bicycle, cruising along, eventually having to go uphill, and then coasting back down again and hitting your rhythm. Then it’s in your body. When I did the interview with Jon Pareles for The New York Times together with Ralf [Hütter] the word “tangible” kept coming up. Ralf said that when he speaks during concerts, he does so from inside the music. For the Trans-Europe Express show, they performed ‘The Hall of Mirrors’ which is all about Echo and Narcissus. These are the audio and visual reflections that are both sent and received, like a radio station transmitting and receiving, an artist looking and being looked at. It’s an excellent metaphor of what’s been done here at the MoMA, which has cost a considerable amount of money to produce and involved an incredible amount of building and restructuring. My colleague from the Whitney thought that the exhibition space had already existed. No, this was created to bring people into the image, into the cube. And within the cube, people are inside the cone of 3-D projection, which extends from the screen onstage to the projector in the back. Both the band and the viewers are literally inside the art. You can’t stand on the side. I told people when they watch, they have to be in the cone.

During the first dress rehearsal, when the sub-bass came on during ‘Kometenmelodie 1’, several light fixtures started rattling. We took the frequency out, because I thought the building would collapse—I thought the paintings would fall off the walls. We ended up solving the problem of course, but it gave us a scare. The fact of the matter is that when you’re curating, especially doing a retrospective, you give up your own personality. It’s the strangest thing. When I was doing Marina Abramovic, I had to completely dive into her world and live her speed and velocity. Or better: stillness and duration. It’s an intimate experience with a work of art. It means you have to be completely available. So I’ve been listening to Kraftwerk straight for the past four months. You know, with every artist, there’s a first work where the nucleus of all future ideas is contained. And that’s extremely important to know when creating a retrospective. Here it’s Autobahn, for me. That’s subjective, of course.

I think Kraftwerk have been artists from the very beginning, but they were kidnapped by their mainstream success. Of course, everybody is happy to be kidnapped by success, but it makes it more difficult to recognize who and what they are. Still, in the sixties and seventies their studio was right next door to Gerhard Richter’s. They could have drilled a hole in the wall and been right there. But honestly, not a lot of people have understood the extent to which Kraftwerk are and were artists, in Germany especially. Of course, I assume that people like Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke got it. Joseph Beuys got it. Werner Herzog and Fassbinder got it. Katharina Sieverding got it. But not many others.

For me, Kraftwerk are very much children of the BRD, the Federal Republic of Germany. I am like a grandchild of the country, and Kraftwerk are father figures. The BRD, like the GDR, dissolved—it doesn’t exist anymore, but artistically speaking, it was all about Kraftwerk, Heinrich Böll and Joseph Beuys. It used to be that Germany had the first truly active Green Party, and culturally—in art and music—this played an important role. Beuys sang ‘Sonne statt Reagan’, and there were massive anti-nuclear protests, especially against the stationing of Pershing missiles. Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz featured Kraftwerk’s ‘Radioactivity’, of course. I see all this in a very specific historical context, but also in an artistic one. The incredible thing is how Kraftwerk have been capable of not just updating but upgrading their material over the course of their careers.

Somehow it seems like people haven’t understood that the retrospective is an exhibition and not just a concert. People just don’t get that, and it’s been very hard to get people into a different mindset. It’s like with movies—film was the leading art form of the twentieth century, and it still hasn’t really made it into art museums. Museums can be so slow. With a time delay, art arrives with cinema, which is something I’m trying to push. I did Doug Aitken at MoMA which was big, cinematic images with no sound, then I did Pipilotti Rist, which was cinematic images with sound, then came Marina Abramovic, which was cinematic image with sound and live performance. And now it’s gone one step further. Kraftwerk is the fourth step. But there’s a fifth step, and I’m not sure what it is yet. A few months ago I went to the Cologne Cathedral to check out Gerhard Richter’s stained-glass works. And all I could think is what it must have been like a few hundred years ago to come from some mud-hut, some tiny town with no electricity, no heating, and see this incredible thing with image and sound. That’s what I imagined seeing and listening to Kraftwerk to be.

WEDNESDAY

Juan Atkins, electronic musician and founding father of Detroit techno

Photo: Luci Lux

The first time I heard Kraftwerk was on The Electrifying Mojo’s radio show in Detroit in the late seventies. This is when FM radio was still young, and there were only, like, three stations. There really was no specific format for FM radio at the time—DJs were allowed to do what they wanted. You heard them play entire albums when they felt like it, which couldn’t be more different from today’s radio format. Mojo used to play ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘We Are The Robots’ pretty regularly, but the first time I heard ‘Robots’ I just froze. My jaw dropped. It just sounded so new and fresh. I mean, I had already been doing electronic music at the time, but the results weren’t so pristine—the sound of computers talking to each other. This sounded like the future, and it was fascinating, because I had just started learning about sequencers and drum programs. In my mind, Kraftwerk were, like, consultants to Roland and Korg and stuff because they had these sounds before any of the machines even appeared on the market.

Needless to say, Kraftwerk definitely influenced my sound, because when I heard their music I automatically knew I had to tighten up what I was doing; I had to make it cleaner and better—though not necessarily more minimal, because what I was doing was pretty minimal for the time. A lot of people think that I was copying Kraftwerk directly, but that’s absolutely not the case. For me, they weren’t any more of an influence than, say, funk—P-Funk especially. I actually had a chance to talk to Florian [Schneider] when we played Tribal Gathering together a few years back. We met up behind the Detroit stage and chatted a bit and I was really surprised to learn that Kraftwerk were hugely influenced by James Brown. Of course, P-Funk was made up of at least half the JB’s first line-up, so somehow Detroit techno was a very natural, even “fated” progression. I mean, there were other funky electronic bands around—Tangerine Dream and Gary Numan and all that—but none were as funky as Kraftwerk. I mean, you could actually play the stuff on black radio, and that wasn’t a small feat. You could go to an all black club in Detroit and when they put on ‘Pocket Calculator’, everybody just went totally crazy.

Kraftwerk’s minimal lyrics were part of their overall concept, and definitely contributed to their special blend. I can say for sure that they put Germany on the map for me. When I was a kid in school in America, the only thing we learned about Germany was World War II. Also, I always had this impression—independently of the war—that Germany was very logical, very machine-oriented. And without a doubt, when I went to the Man Machine show at the MoMA retrospective, I could definitely hear the way they combined the machine-driven syncopations with a more human take on improvisation. And the visuals were phenomenal. I had only heard after the fact that Ralf Hütter had played an important role in choosing both Francois K and I to do our DJ sets for the Kraftwerk exhibit at the geodesic dome at PS1. I’m proud to have been a part of it.

Published August 16, 2012.