A week in the life: 168 hrs Kraftwerk, NYC part 2

Read part 1 here.

WEDNESDAY

Ruza ‘Kool Lady’ Blue, producer, promoter, and founder of legendary club The Roxy, NYC’s first hip-hop club

I originally came to New York in 1981 from London to run a fashion store for Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood called Worlds End 2 in Soho. At the time I had been living in the Chelsea Hotel and fashion and music for me were always intimately connected, something that both Malcom and Vivienne understood very well. In the eighties, the burgeoning hip-hop scene wasn’t really that organized, and there was no hip-hop scene in downtown Manhattan. But there were DJs, MCs, B-Boys, B-Girls, dancers, and graf artists scattered all over the place up in the Bronx, so I basically went up there and brought them all downtown, and organized them. They had no idea where this journey would take them, nor did I.

I had first been exposed to hip-hop through watching Afrika Bambaataa and The Rock Steady Crew open for Bow Wow Wow at The Ritz, which was a show Malcom had actually organized. That was when my mouth dropped and hip-hop replaced punk for me in terms of main musical interests. In the early days it was all so experimental, and it was never about making money or bling-bling, or shareholder meetings, but more about unity and fun and dancing to incredible music. My contribution was, I guess, combining all of these elements into the electronic dance club context, and it worked. It was mad. You could feel an overwhelming sense that things were shifting into a new era of explosive creative freedom and change in NYC. Mash-up culture was born and DIY was the name of the game. You could do anything and no one would judge you.

The hip-hop and downtown scenes mixed fantastically; like the perfect cocktail and a brilliant sense of humor. I had this gut feeling it would work and after a short spell promoting parties at Club Negril, which got closed down, I had the idea to move the scene and start the Roxy parties, which ended up being game-changing. I always wanted to open a massive dance club in NYC on the euro-electro music tip— people dancing to the sounds of Kraftwerk, Ultravox,and the like. But I wanted to do it with a twist. I was particularly inspired by the blitz-electro-new-romantic scene in London and what DJ Rusty Egan was doing, but I didn’t want it to be so exclusive.

I think the Roxy was the first racially diverse electronic dance club ever, and it became the blue- print for so many important clubs. We had everyone from punks like John Lydon, to serious couture fashionistas like Carolina Herrera, to Madonna, to twelve-year-old B- Boys, DJs like Bambaataa, to Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Mick Jagger, Leigh Bowery, Debbie Harry, Julian Schnabel, and the ubiquitous Glenn O’Brien. And then there was all the people from the Bronx . . . All barriers came down and there were absolutely no age limits. We shunned Studio 54’s elitist policy, and we knew we were on the right track because the juxtaposition of these diverse sets of people was so mind blowing. At the time, hip-hop culture was all embracing: no one cared if you were a tranny, had blue hair or wore spandex or a Sex Pistols t-shirt. This was the party where white people first saw all four elements of hip-hop culture showcased in one place in downtown NYC and in a massive dance club environment.

There are so many stories to tell, I can’t think of them all . . . I remember booking Malcolm McLaren to perform his hit ‘Buffalo Gals’ at the club, and he went missing the night of his show. He had serious stage fright, but I managed to locate him in a bar somewhere in Midtown and convince him to come to the club and that things would be all right. It turned out great in the end, of course. Prior to that, I managed to convince Malcolm to give me a copy of The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle to show at the club. That was the first time the film was ever shown in America, and what a pivotal night that was; when hip-hop met punk face-to- face. The right chemistry was there so I ended up screening the film every other week for a laugh. I felt like a mad scientist mixing and mashing up cultures to create a new conversation.

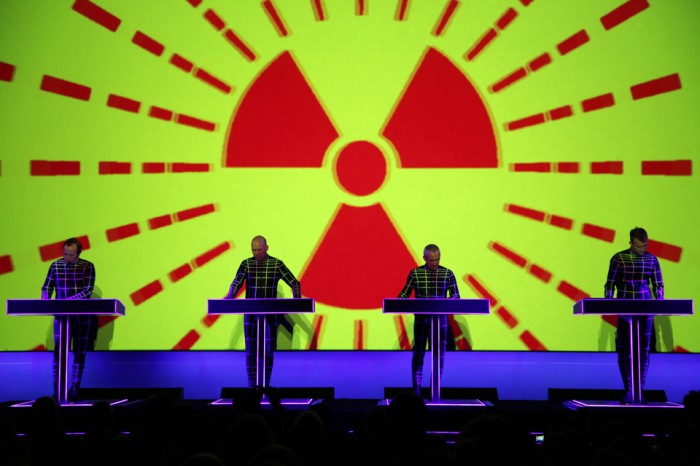

Kraftwerk were very, very important to my club. Everyone danced to Kraftwerk—and I mean everyone. I made sure their songs were played every week, and it quickly became part of the soundtrack. I find it extremely difficult to rate their output, because virtually everything has been so influential and so high quality. But if I had to choose, I would say Radio-Activity, Trans- Europe Express, and Computer World are my absolute favorites. I’ve also had the chance to see them live a couple of times, most recently at the MoMA retrospective. All I could think is how timeless and relevant this band is, especially in today’s Apple computer culture. And I loved the idea of wearing the 3-D glasses. I attended Trans- Europe Expresstogether with Afrika Bambaataa, and it brought back a lot of good memories of the Roxy and ‘Planet Rock’. Of course, ‘Numbers’ and ‘Trans-Europe Ex- press’ were classic Roxy anthems. Musically, I am not sure you can overestimate Kraftwerk’s influence. Like hip-hop, Kraftwerk is everywhere and still miles ahead of their time. For me, Kraftwerk was the perfect mash-up band as far as representing the future goes. And they had a message. Even though their lyrics were minimal, they remain incredibly poignant, even today. ‘Radioactivity’ is perhaps the perfect example.

THURSDAY

Afrika Bambaataa, producer, DJ, and founding member of Soulsonic Force and founder of Zulu Nation

It’s always interesting for me to see a crowd dancing to music that’s ‘foreign’, especially if the lyrics are in a foreign language. Miriam Makeba, Manu Dibango, Salsa, Falco—you name it. That’s why when I first picked up a copy of the English version Trans-Europe Express, I made sure to pick up a German copy too. I love the crossing over. That’s what electro-funk was all about in the beginning. I actually listened to it for the first time on one of those little record players—the ones that have their own speaker. I liked it, but only when I put it on my big sound system was I really blown away. All I could think was, “I’m gonna jam this mother!”

The first time I played it was at the Bronx River Center and immediately people understood. I always had the most progressive hip-hop audience. Most of the other DJs waited to see what my audience was into before they played anything at their function. They knew: Bambaataa’s crazy and he’ll play anything, so I was like the one in the laboratory doing the experiments first, and at a special place. In the beginning, Bronx River Center had mostly black and Latino partygoers from the Bronx and north Manhattan. Then as things progressed and we started playing on different systems and downtown and all that, that’s when all the new wavers started coming and it became a whole mixed atmosphere from all over the city. But most, like, ‘famous’ people came to see us—Zulu Nation and Soulsonic Force—at the Roxy. That’s how the electro-funk spread. But it’s not exactly where it began.

To me, Kraftwerk always sounded European. Trans-Europe Express especially. But I understood the train and travel as a metaphor for transporting the sound through the whole universe, and so was their influence and power. Whenever I felt the band’s vibration all I could think of is that this is some other type of shit. This is the music for the future and for space travels— along with the funk of what was happening with James Brown and Sly Stone and George Clinton. Of course, I was listening to a lot of Yellow Magic Orchestra and Gary Numan, as well as Dick Hyman’s Moog sound, and music from John Carpenter’s Halloween. When you put all that together, then you get electro-funk, which is what we were doing. Freestyle and Miami bass— that’s where it all came from. That’s the true techno-pop.

With ‘Planet Rock’ I was hoping to stretch the hip-hop community’s musical spectrum on the one hand, and the new wavers’ on the other. It was about channelling the vibrations of the supreme force, of the universe, to maximum effect, even beyond earth to the extra terrestrials. Kraftwerk, James, Sly, and George played exactly that. But Kraftwerk brought the funk with machines and computers. They might not have thought they were doing funk, but they were doing funk. When you see older movies about space and the future, it’s filled with stuff like spaceships and rayguns. The newer ones like The Matrix or whatever have their own vision of what’s next. Kraftwerk does all that with music.

When I met Kraftwerk in a club in Paris in the eighties, there was mutual respect. We talked about doing something together, but that happens all the time. Unfortunately we never got to make that happen. But I did get to record in Conny Plank’s studio with Afrika Islam. It’s interesting to think about how Kraftwerk was reinterpreted in America, and then through a very different filter came back to Germany to influence all sorts of electronic and techno acts. The name WestBam, short for Westfalia Bambaataa, says it all.

I’m definitely glad I had the opportunity to catch them at the MoMA. Of course, I’d seen them play live before and I have all sorts of live recordings from back in the day, but this was a different thing. I really enjoyed it, but to be perfectly honest, it wasn’t the same as hearing them in a club.

Published August 23, 2012.