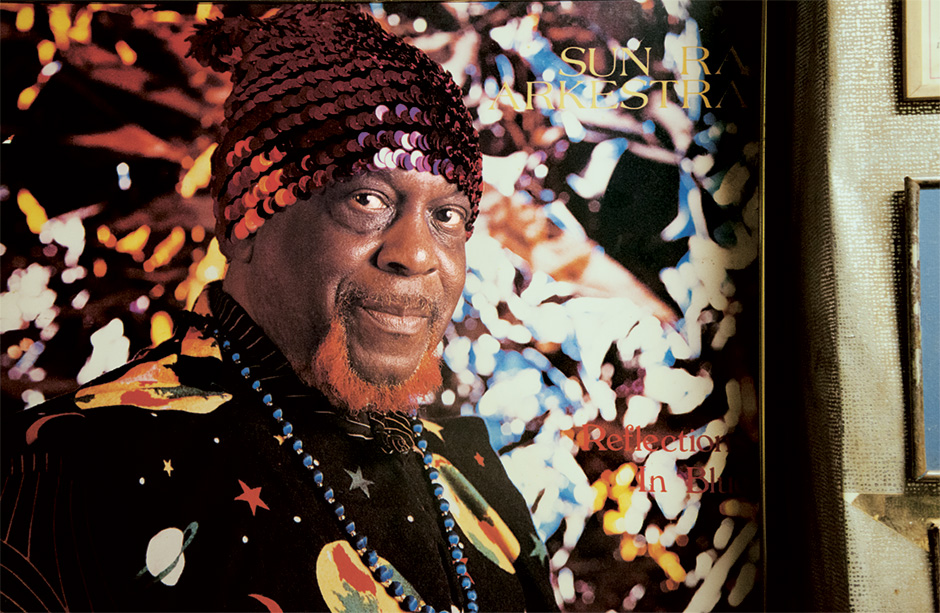

André Vida and Max Dax talk to Marshall Allen of The Sun Ra Arkestra

All photos except header by Luci Lux.

Meeting the Sun Ra Arkestra’s director Marshall Allen at the group commune in Philadelphia wasn’t quite space travel, but it was a kind of time travel. The eighty-nine year-old alto sax and woodwinds maestro was eager to discuss the teachings and creative punishments of former bandleader Sun Ra, one the most singular figures in modern jazz. Indeed, Ra was amongst the first to experiment extensively with elements of electronic music, anticipating what would become the musical language of the 21st century.

Mr. Allen, it’s a great pleasure to meet you here in this particular house, where you and Sun Ra used to rehearse with the Arkestra.

Yeah, this house has seen and heard a lot in the past decades. Actually, I just woke up from a nap, I heard melodies playing in my dream. It was a late night out yesterday.

You went clubbing?

No, just some overdubs in the studio. But even today, recordings are best done during the late hours.

Are you recording new music for the Sun Ra Arkestra?

No, last night I was with a friend of mine, a poet, who needed some background music for his poems. He asked me, so I did it for him. I came back early this morning and then I needed some sleep.

So, that’s what you do at night in Philadelphia?

I’m in this house all the time—that is, when I’m in town. I am away so often, I never stay home here much. We just played at Lincoln Center in New York on Saturday. And the week before that we played in Switzerland. And prior to that I was in Italy and London. I travel a lot.

I want to pick up a trail from a previous issue of Electronic Beats in which Bobby Gillespie mentioned that he invited you to record with his band Primal Scream in London to kill some time while you were forced to stay during the volcanic eruptions in Iceland in 2010.

I remember. We were supposed to leave Europe the day it started. But we couldn’t get out because our flights got cancelled. So we had to stay a few more days in London. I figure we’d add an extra night and play another concert. And yes, we jammed with… what was their name again?

Primal Scream. How were the sessions?

Good, I guess. There have been so many sessions in my life. I start to mix up names and places. I might have received a complimentary copy of their finished album and have put it on one of the many stacks that you can see here in my house. I actually play with a lot of young folks. I see the whole thing as an adventure, as I like all kinds of music. I am not just doing one thing, I am doing anything if I find a good thing in it. Recording with Primal Scream seemed natural to me because it meant we didn’t have to hang around outside under the grey London skies.

Would you say traveling is an integral aspect of your lifestyle?

Yes, and it’s been like that since 1942. You know, I was in the US army and I fought in France. After the war, I just kept on staying in Paris where I also went to music school until 1949, which is when I left France for Chicago. But after a while the musicians from Chicago were starting to move to New York. So we got in the migration run and stayed in New York for a decade. But the last forty years we all stayed in Philadelphia, which is where I inherited my father’s house. Sun Ra needed a place to rehearse—for his band, for us—so I convinced him to take the house for free and live in it.

The neighbors never complained?

No, no, we got some good neighbors here. The Ra house is good for the neighborhood—Germantown is pretty nice but sometimes at night it can get kind of scary. But we’ve been here since 1969 and we practice all night, all day.

The neighbors like music?

The police once knocked on our door, and Sun Ra told them he was playing a joyful noise. But other than that, no complaints.

You still use this house for rehearsals?

We lived here and we rehearsed all day. We’d take a break and then practice half the night, right in this room here. But we also record here. And the nucleus of the band still lives here: I got to have people around me to keep the music going. You know, all the original instruments are still here. Sun Ra used to play on them.

So this is a very special house not only for the Arkestra but also for American history.

It’s a commune. All the musicians living here would have other skills as well. One could fix doors, another one could cook, others were good painters. In the commune, we were doing everything ourselves. We wouldn’t need outside help, we were truly independent from the outside world. In this house, Ra was telling us that we had to do our own everything. We even sewed our own costumes. We had our needles and thread and a sewing machine and designed and tailored our own show uniforms. We didn’t have no money, so what could we do? We then learned to manage ourselves; we learned to read contracts, because if you don’t learn that, it’s always the middle men who’d rip you off. So we made our albums, made our music, made our covers, made our own designs. We even had a vinyl press for some years and we glued the label on the LP’s ourselves. Over the decades we eventually manufactured some 500,000 records in this house.

Do you still have copies of these handmade records for sale?

I think they’re all sold by now.

Above: Danny Ray Thompson has played flute and saxophone on and off in the Sun Ra Arkestra since 1967. Rejoining the band in 2002, he also runs a private airport shuttle service and has worked for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Have the routines of rehearsing changed since Sun Ra’s passing?

No, it’s the same routine we’ve always had: no women or drugs or anything like that are allowed in these walls. It’s important that the musicians have a place where they can practice twenty-four hours a day. It gets difficult if you don’t have a place like that. But contrary to Sun Ra, who basically practiced all the time and couldn’t even get out the house, I turned it down to three days a week. Monday, Wednesday and Saturday.

In New York I talked to the Arkestra’s drummer Craig Haynes who explained to me how you were prepping for the Lincoln Center gig. He said you were rehearsing a lot, but when you actually went on stage you hardly played anything of what you’d rehearsed.

We never do. I learned this from Sun Ra: you rehearse here for a month for a gig but you wouldn’t play any of the tunes. This way everybody was sharp and on edge. It’s actually a perfect way to keep musicians mentally aware.

Nowadays when you watch a band you can be quite sure that they’ve rehearsed everything. Nothing could go wrong. Your concept on the other hand allows for some great inspirational moments that might result from accidents or coincidences.

Well, that’s the idea behind it. Music is alive and it’s always about the musicians, the sound of the room and the audience. And this means that everything can change at any time because you are well prepared for change. You have to adapt to the idea that everything changes all the time simply because the vibrations of the day are different compared to yesterday. That obliges you to change something. If you are really strict and repeat the rehearsed music perfectly then it won’t work because it doesn’t take into account the vibrations.

And you have the necessary antennas to feel these vibrations?

Sure.

It’s not academic.

That’s right. It’s nothing you plan, but thanks to rehearsing so intensely we got the arrangements and all the melodies and all the difficult music and all of the intricacies in our hearts. We can still play loose, free from the academic spirit. Ra told us to have our memory tight to remember things he’d play to us because he’d not play them again after we’d memorized them, you see? He’d play something different instead. Sun Ra had three, four or even five arrangements on any tune. And according to where we were, one of them would probably fit.

But how did or do you memorize all these various versions of different tunes?

The memory… You have to know your book! Sun Ra would surprise us at any time. He’d play four bars on you and if he realized that you ain’t got your music on you, he’d change the song right in the middle of the introduction.

Just to get this straight: Did he notate or did he not? Do you rehearse and play on notation or not?

Everyone has a different way to memorize. We got scribble-scrabbles all over the page. We all have our own code to remember something once we are one stage. But yes, Ra always did notate.

Have you ever considered putting together Sun Ra’s notations in a book?

Well, a lot of people are doing that. But we don’t need that book. The sheets are everywhere—in this house, in other places. Ra did it purposely, he spread the music everywhere, and the idea is everything everywhere. It was like the big giveaway, Lord, the big giveaway. You see, that was his way of doing it and less expensive than a book. If you want to get your ideas out there, just put them out there. Spread the music around.

But didn’t you make your own book of melodies?

Yeah, I’m always writing my melodies down. I bring them to the copyright office, and by now I got a whole book of melodies. I don’t know what I will do with them, but I got them well collected. Unlike me, Sun Ra has written thousands of tunes. You may wonder how he had all the time to do that, but he was just consistent. In his writing, his ideas and his music his great discipline surfaced. Put something in it and you get something out.

Above: At fifty-six, Craig Holiday Haynes, son of the legendary jazz drummer Roy Haynes, is the youngest member of the Sun Ra Arkestra.

So in live situations you’re directing the band. How do you do that?

I’d come down with a chord, open it up, and they don’t know anything, so they’re watching me. And that way I can guide them along. It’s a method to make them pay attention. That’s the way you do music when it’s not being read. We have to all come into one and then we take it from there—anywhere it goes. And honestly, there is no other way to do it. If you don’t play the music, it will disappear. As a matter of fact, you have to know the musicians you are working with. It’s like tailoring the arrangements for the musicians while performing. That’s the reason why you have to live together and bind and co-ordinate.

You are essentially describing a living organism, right? A living musical organism.

That’s true. Sun Ra knew he could count on us. He didn’t come in knowing anything. He’d come to find out what’s going on, what you have to do, if you’re listening to each other.

And how important are recordings in that regard? They could serve as a memory as well.

I’ve only done a few since Sun Ra passed, but he did 500, 600, maybe a thousand. He had so much music and he wrote music everyday. As a band, we haven’t played all this music yet. So why record?

So you’re in a sense like a living archive?

He left a treasure house of music, and I got the original notations. I got most of all of the music he wrote, and I even remember the combinations of what goes with what. But then, as time goes by, you lose some combinations of different melodies he had mixed together, you just forget them. And if that happens, then I’ll just make a new recipe with the known melodies. And put my own things in there. It’s the same thing with Sun Ra’s music because if he wrote a tune: it’s music, it’s notes up and down, but he has a secret way of phrasing he had to show you—otherwise you wouldn’t get it. Like a good chef knows how to read a recipe and how to tweak it, he’d show us how to turn the music alive, in the same way a chef has a secret formula. Ra got a little something in there that made the food better.

You also eat here?

If one of us can cook, that’s what we eat. If you can’t cook you go to the restaurant and eat there. At the end of the day everything is about discipline. You know that you’re doing a job and you know that you’re doing what you want to do and you do it in good spirit.

Let’s talk about Sun Ra’s recipe for moon stew.

Yeah, he had a recipe. He put everything in it and all of it was healthy. But the way he mixed it and made it taste—that was the secret. In that sense, he thought like a chef.

Miles Davis, they say, was a good cook as well.

Sun Ra had all these recipes that he’d cook for us. I tried making the moon stew myself. I used all the same ingredients like him, but it didn’t taste like his. These days I’m teaching guys how to phrase a passage the Sun Ra way, but I couldn’t tell them how to cook.

Above: The practice space of the Sun Ra Arkestra, located on the house’s ground floor, has seen more than four decades of continuous musical exploration.

When you first met Sun Ra, the story goes that you went to his place and played what he told you to, but he was somehow disappointed with everything you played correctly.

He was disappointed because I played it too accordingly. He obviously noted that I got a beautiful tone, but that’s not what he wanted in the first place. He wanted someone who was willing to go beyond what’s notated or what he asked for. For me, this was irritating. I remember it made me nervous that he always said: “That’s good, that’s right—but it’s just not what I want.”

How did you come up with this crazy saxophone approach of yours. It’s so unique.

Well, that’s what I was telling you: I was playing nice a smooth and pretty saxophone with beautiful tone and sound and execution, but Sun Ra would always say: “It’s good—nothing wrong with it—but it’s not what I want!” So I started to do what they call “anything”, and that’s slang for: everything wrong. And he liked it! I learned from him that to do skillfully wrong is still doing something but it’s not doing it in the sense of calculated thinking. It’s just “doing”, and that was the key to all the spiritual things that Ra tried to address with his music. From then on we got along very well.

By doing the wrong thing.

Ra used to always make observations about the question of doing something right or doing it wrong. He’d always say: make a mistake!

And then after that, another mistake?

Yes! If you make a mistake or do something wrong, then make another mistake and another one and eventually this will lead you to something right.

And how would he communicate to you what he really wanted?

He’d always sing it to you: dah dah dah dah dee dah dah dee… His way of doing it was a way of phrasing just before the beat. Like syncopated, like swing. Just before, not on. He had some odd ways of teaching us!

That’s what computers will never learn.

For sure they’ll never learn to swing. In the beginning I’d bend certain notes and play a passage, and it was always the same music. But when Ra would take the lead, it would sound completely different. He had a unique flow and like with the Duke Ellington Orchestra, this flow would infect how we’d play the music and thus distinguish our band from any other band. You could say the same thing about the Miles Davis band. Duke and Sun Ra and Miles, they were all bandleaders, as opposed to just good musicians playing. Not everybody is born a bandleader. Everybody can have a big band, but being a leader is about being a leader. It’s the same thing in life and in war. You get some good ones and you get some, well, not so good ones.

Above: Every corner of the house contains pictures and memorabilia serving as a reminder of Sun Ra’s role as the group’s founder and patron saint.

Swing tunes have always played a significant role in the Arkestra, especially when you play live. You reference genres and ideas inherited in jazz from decades ago, but by playing them today and in your style, it’s not a retro thing at all. You basically remind people that there is something from the past that can be brought to life again.

Sun Ra told me once there’s a thousand ways to play one note. So, there’s always just another way to play the same note, and you have to remember them all. Because when you are out there on stage and performing, you’re going to need to remember. As I said before, we play the tunes without charts. That’s the old swing way to do it. Duke Ellington’s big band didn’t need charts, just their memory, to be tight and precise. I play a whole gig without charts, too. And that’s what defines swing, really.

Do you think today’s generation of musicians would be able to do that? To function as a band like the organism you’ve described before and to memorize all these complicated arrangements?

If you want to play swing, you can’t just duplicate a paragon. You have to rely on your own personality and your own way of speaking. Louis Armstrong once said: “You play what you is!” And there are all these colors in the sound, and all these individual ideas flowing through Duke Ellington’s band. And you could tell the difference between Duke and Count Basie and Jimmy Lunceford because each of them had their own particular style that they developed, even the little bands. You see, Sun Ra had his own way of coloring sounds. Unlike Duke Ellington or Count Basie, he used some dark colors. Ra was masterful in terms of design, he was fully aware that the coloring made the band sound in a unique way.

Is this common, to think in colors as a musician?

Sure! He would write the notations in dark colors to stress that—all in his kind of thick, kind of heavy handwriting. And you don’t necessarily have to have a whole room full of musicians to get that heavy, thick sound, because the way he voices the music, his voicing of a chord, using under and overtones, gave the whole thing a very individual color.

When is a band considered a big band? Is it ten, twenty people or thirty?

It doesn’t matter as you are always dealing with sound, a sound that can make you happy or that can make you cry or that can heal you. So, as a musician, you’re dealing with sound first to enlighten yourself. Then you give it to others. Because when you’re not playing music for money or show or fame, you’re playing it for what it is, and that’s to heal. So, first comes the music, the sound body, the sound mind. We all know that music can heal as well as music can kill. Music can do all these different things, according to the way you play it. They invented a sound gun that can destroy thirteen-inch reinforced concrete: pow! They got a sound gun, the war people.

That’s what they call sonic warfare.

The masters of war got all that for killing. But I’m using sound for healing and your well-being and your enlightenment.

What about the phrase that’s often printed on Sun Ra Arkestra’s record sleeves: “As all marines are rifle men, all members of the Arkestra are percussionists.” Why do you draw that analogy to war here?

Well, we always played for the people, not in competition with other bands. Enlightening people, healing them—that always was our purpose. But I’ve seen music being played and audiences throwing bottles at the musicians. I’ve seen this happen in France and Italy to Jerry Lee Lewis and his band. We were playing right after him along with the Mexican Ballet, and, man, I was scared. But you have to go on stage because as a musician you are a soldier. And so we went out there and we played a different type of thing and the French all quieted down. The soldier’s ethic is a good ethic as it means discipline. I bet you will find a lot of philosophy books that will prove this thesis right. But talking of the Arkestra we have the self-understanding of a show band. And for that reason we dress up in costumes and bright colors. It’s not just us musicians sitting up there and playing.

Were there other soldier ethics in the Sun Ra Arkestra?

You put on your costume like you put on a uniform and suddenly the vibrations and thoughts change.

Why didn’t he call it the Sun Ra Army then?

Well, they got guns and we only got saxophones and flutes and piccolos. Then again, musicians call their horns axes. It’s slang. But having said that, different musicians got different ideas of what they want to do. Every musician has his own style and his own type of music. So, if you’re open to that—that’s good. If you want to play straight jazz, you’ll play straight jazz. And if you want to be in a band, you’ll play in a band and become a part of that band. In that sense, I never wanted to be myself, an individual playing music. I always wanted to be with others, I always wanted to be a part of a band, a part of an organism. That’s what it is and that’s why my life is being a part of a big band. To be together on the same vibration and to build a thing—that’s the discipline and precision I’m talking about. A man cannot learn without discipline. It’s a soldier’s code. Discipline is the key to everything. It’s the essence of any army or any band or whatever you are part of.

Didn’t Sun Ra have his own jail for musicians who were lacking that ethos?

He called it his “Ra jail”: If you messed up his music then you were going in the Ra jail. He wasn’t any different in this regard to all the other masters that I’ve met in my life, where if you mess up their music they become another person. Charlie Mingus would literally throw something at you, and Sun Ra would cuss you out on stage. He actually had a lot of things he would end up doing to you. But the worst thing for sure was the Ra jail, because the Ra jail was live on stage. You couldn’t leave the stage, you couldn’t go nowhere, you couldn’t do nothing about it. You had to sit right there in front of the audience and take it. And he’d get up and announce you and point his finger at you: “This is so and so, a nice sax player, but there’s one thing he hasn’t got: discipline. I don’t care how good you are. You have no discipline and therefore you sit and watch the band and learn.” That was the Ra jail. The music continued, but without one of us contributing. He’d just give another musician in the Arkestra his part. He got it covered as the concert went on. So, for instance, if the trumpet was out all he needed was me in there with the alto sax to sound like a trumpet. In such moments of punishment, I was always the substitute.

When you were playing with Sun Ra how did it work with other music? Were you checking out records of other big bands?

We listened to everybody. See, that’s the thing they didn’t know about Sun Ra. He listened to everybody. He wasn’t prejudiced towards one type of thing.

Do you recall some examples of music he was listening to that surprised you?

Well, he was always surprising me. That’s why I stayed so long and why I continue this endeavor to this day. That was the mastery of all these things. He taught us how to balance thought with the spirit. As a musician, you can damage people if you’re not sincere and have no discipline.

Above: On the house’s second floor, Marshall Allen improvises on a small harp.

You played with Sun Ra for almost four decades. After he passed you then became the director of the Sun Ra Arkestra. How do you fill this role with legitimacy?

I’m carrying the name because I was there all the time and because it was Sun Ra who taught me how to play his music and what his music means. But more than anything else, all this is also about keepin’ on keepin’ on. If you want a better world, you have to create better music. It’s as simple as that. We’re in a lot of trouble. We need musicians that heal people.

The Sun Ra Arkestra is often referred to as imagining the future. The phrase “space is the place” is telling. But also you freed jazz from many of its limitations.

At the end of the day it’s always about being open. When jazz freed itself and became free jazz, not everybody in the audiences would get it. Some might have thought that the band was still warming up. They probably thought that the music they were listening to was just noise. People had this preconception in their minds how jazz had to sound in their ears. Sun Ra always used to say that we were playing the music for the twenty-first century, and he said that way back in the fifties. At the same time he wanted to be successful, but he always stressed the fact that we’d have to wait until the twenty-first century! And I said: But that’s about another forty-seven years from here. And he’d be telling me I have to go through this scramble for fifty-seven years before I could be successful.

Sun Ra was also experimental when it came to electronic music.

Sun Ra was the first to use electronic keyboards in jazz because he was mentally living far in the future. He began to mix all these things together that he was hearing in his head. And it’s all out there in the universe anyways. Even today you could listen to the music of the twenty-second century in your head. He started to use electronic sounds at the time when I joined the band. Ra said about electronic music that it was to come in the future and that it would be like a universal language that anticipated the future and that could be understood by everybody on the planet. He would draw his own conclusions from having foreseen the future. He’d say: “Now you drummers should have some more discipline and do what I tell you to do because in the future they gonna have electronic drums and then they won’t need you anymore.” He wizened us up by telling us that the electronic age was coming. He already knew that. He and Miles Davis, probably.

Do you listen to contemporary electronic music?

I listen to everything. You turn the music on and I’ll listen. That’s what Bobby Gillespie did with us. He played music to us. And remember, when the Moog synthesizer came along, one of them was built for Sun Ra especially. And before that we were going around to the universities and into the universities’ electronic sound departments developing different sounds for them. So we could duplicate sounds there, and they added their own sounds. Nowadays you got everything in the machines you can buy. You just have to push a button to get everything now. But we’ve been hearing these sounds all our life. I’ve been living in the twenty-first century for more than fifty years now.

So after all these years, you are now living in the present instead of the future.

The present is in the present. I’m eighty-nine now. I am enjoying the present like a memory of the past.

According to you, the sheet music that Sun Ra left behind can be understood as predictions of the future, which essentially means of current times, right?

Absolutely. Ra could foresee these things like other men in the world foresee some scientific things in the future—and win Nobel prizes for it. Ra too was like some scientist who understood the future. You just had to wait your turn and you see. And to this day he’s proven right most everything he had been saying.

And how do you store or archive his sheet music and notation? I mean: Have you ever made copies? There could be a fire that destroys everything.

Actually, no! There are no copies, only original notations. You know, I play all night and I play something different each time, and that’s what I teach the other musicians. That’s the gift Sun Ra left for the musicians to carry on with the idea of bringing out the music from the notes: it’s about the spirit, not the sheets. So just like I could take the band and go play a gig without written arrangements, I’d still know how to phrase it. It’s like poetry. I know a lot of ways how to create something from nothing. It’s like none of us will forget the lyrics to “Nuclear War”—which is, by the way, still a scary song to sing.

Why?

Because it’s still so true, you know? To sing, “It’s a motherfucker don’t you know / push that button your ass gotta go” in public is still a bold statement. But it’s true. It’s as true as dropping a bomb on real people. Yeah, it’s that true. ~

Above: An alien casually hangs out in the house’s first floor reminding us of the meaning of jazz. What’s that you ask? Space travel, of course.

Published March 31, 2014. Words by Andre Vida & Max Dax.