“Anything can be pop nowadays”: Pet Shop Boys Interviewed

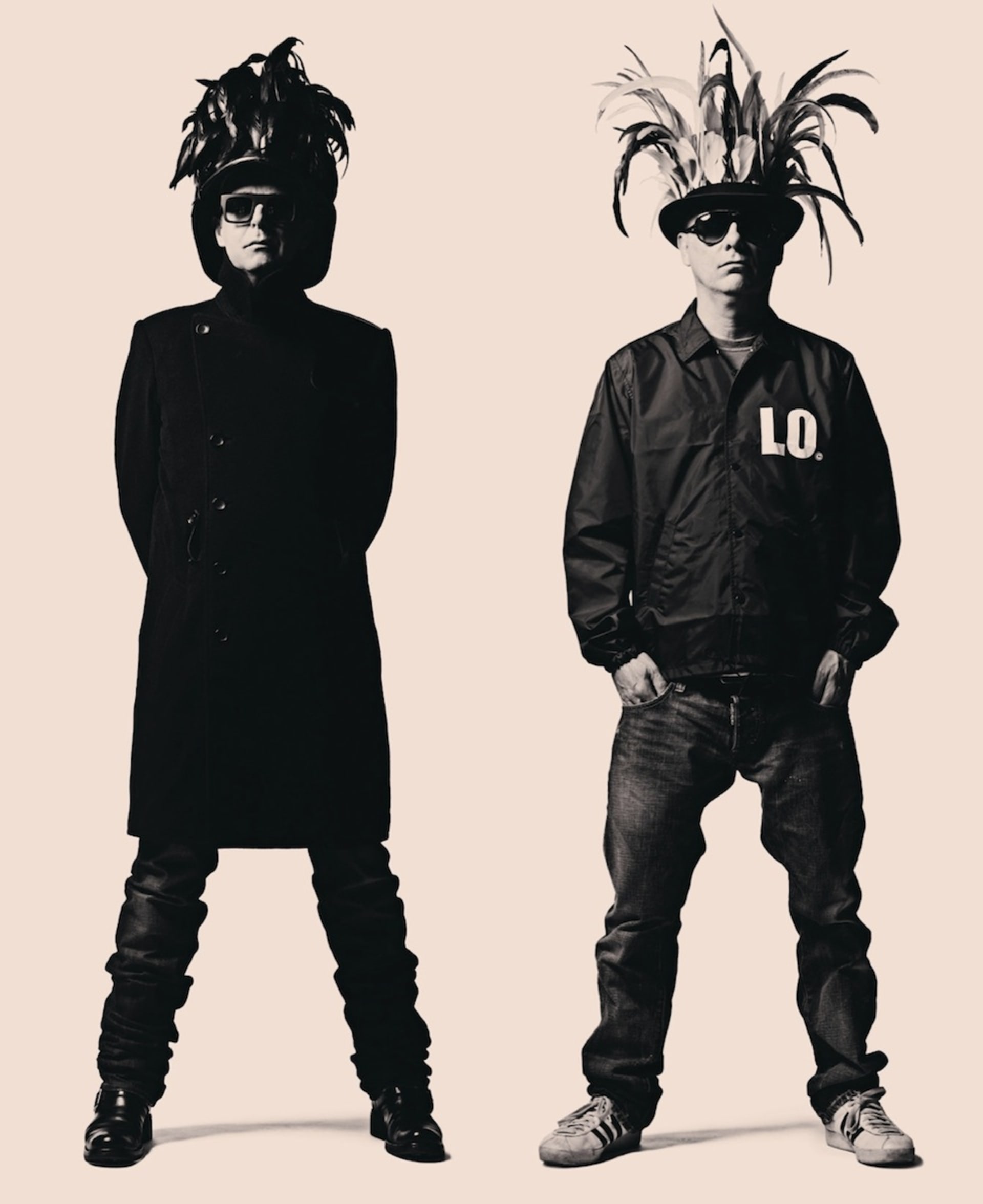

In a music world obsessed with artistic authenticity, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe of the Pet Shop Boys are unapologetic pop supremacists and vocal critics of the contrived poses of rock and roll realness. And why shouldn’t they be? Having sold more than 100,000,000 albums, the pair speaks with the authority of the most successful British duo in history—a feat accomplished through exposing the value of surface sophistication and giving a voice to the snarky and un-rebellious. Oh yeah, and by writing unquestionably brilliant songs that make queer fans proud to be out and straight fans secretly proud to be in. On Elysium, Lowe and Tennant have once again dreamed our reality. Photo: Pelle Crépin

Your elegantly designed website informs us that today, exactly fifteen years ago, you shook hands with Tony Blair in No. 10 Downing Street.

Neil Tennant: Did we?

Chris Lowe: What’s the day today? Is it fifteen years already?

NT: Let me think: Blair won the election on May 1st, 1997. Actually, he had invited me. And I asked Chris if he wanted to go too, because I had got plus one, because I’d been a donor to the Labour Party. I’d actually given them money from Neil Kinnock onwards. One day, I stopped donating. And you know what the best thing was? They didn’t notice!

There’s two reasons why I think the 1997 Blair encounter is remarkable. The first one is obvious. Does it do any good if pop stars shake hands with presidents or prime ministers? Isn’t this a wickedly tricky situation?

NT: I’d say it’s nothing special. There’s a long tradition in Britain that allows exactly that. It’s no big deal. Since the time when Harold Wilson was Labour Prime Minister in the sixties, the government has celebrated British creative industries. Just take the famous picture of designer Katharine Hamnett arriving at Downing Street for a celebration for the fashion industry—wearing the “58% DON’T WANT PERSHING” t-shirt. And you cannot forget that in 1997 we’d had a Tory government for eighteen years. And the new Labour government—they even liked to be called New Labour—seemed like a really fresh thing. For instance there were two openly gay men in the cabinet. That was a sea change in British politics.

There were no gay Tories?

NT: They had gay members, but they wouldn’t out themselves. But what was the second reason for your question?

When you realize that you’ve been invited to Downing Street fifteen years ago—don’t you think sometimes that time is running fast?

NT: It does, indeed.

The new Pet Shop Boys album Elysium has this sense of awareness that you are getting older. Once in an interview for Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine you asked Elton John if aging in the realm of pop was an issue to him.

NT: That was also fifteen years ago, in 1997. But I don’t remember what Elton replied.

He said: “I’m still as fascinated with the music business.”

NT: I’d say an equally good answer would have been: “You get used to it.” As a matter of fact, sooner or later everyone will realize how quickly time passes, how quickly a year passes, how quickly the seasons change . . . We are moving towards extinction. But in terms of being in the music business or in the world of musicians, there are two generations above the Pet Shop Boys. So I’d say we’ve got used to that world. The Rolling Stones are still touring. Paul McCartney is seventy and he still does concerts.

Bob Dylan is even seventy-one.

NT: Everybody seems to have become used to the idea that a pop star can be seventy or older. It’s only twenty years ago that the NME wrote: “Pet Shop Boys—two men who are pushing forty.” Like if this was supposed to be something bad. Nowadays people don’t say that so much anymore. You either are or are not making a record that people want to listen to.

Would you agree that Dylan was the first real pop star to age in public? And, by doing so, became a role model of sorts?

NT: The point is that he has written songs from that perspective for some time now. That’s the difference. We do the same. Elysium is an album that has been made by two men in their fifties. And yet it’s still pop music. So, in a way, this is sort of a strange dialectic that pop in theory is a young people’s musical form and it can be about growing old.

Would you therefore say that the meaning of the term “pop” has changed? Or does it only depend on the perspective you write your songs from?

NT: Is Dylan pop music?

In the Warholian sense? I’d probably say yes. But of course he ultimately pursued the tradition of a folk singer.

NT: I don’t think Dylan is pop, really. I think it’s much more difficult being Mick Jagger than it is to be Bob Dylan. As Bob Dylan you are allowed, even encouraged, to look old. Although there is a side to Bob Dylan which I think is always overlooked, because Dylan at all times, in any given period, has had a strong image. He grew a moustache and wears hats—he’s even occasionally worn make-up. I mean, first he dressed up as a folk singer. Then he came to England in the sixties, went shopping in Carnaby Street and became all hip and snappy. He hung out with The Beatles too . . . You must not underestimate the power of an image. He’s probably got a style advisor somewhere. In that sense, yes, he is pop. But musically, I think he doesn’t fall into the regular pattern of a pop star because he is not selling sex. Mick Jagger on the other hand, like Madonna, is always selling sex. And Mick Jagger, to his credit, is doing it now in his late sixties.

Have you seen him lately?

NT: I saw a picture from Jade Jagger’s wedding on the Hello! magazine cover. You look at him and think: Wow, Mick Jagger! He’s made craggy work. He has had no facelift, no Botox. He’s very lined. But he still looks glamorous. He’s still thin, and he has this slightly feminine way of standing. I don’t know, he had a lot of charisma in that picture.

Pet Shop Boys are considered pop in the true meaning of the word. How would you define pop nowadays? Funny enough, the word became a common term in the sixties, already some fifty years ago…

NT:When did pop first appear as a term? If I remember correctly, pop emerged in the fifties independently in the UK and in America. In Britain I think Richard Hamilton coined the term.

Richard Hamilton was Bryan Ferry’s professor in art school, wasn’t he?

NT: He was, yes. And you know, one time we used to worry whether we were a pop group or not. But of course we realized we were a pop group and we totally still are. We used to hate the fake authenticity that rock claimed to have. By the way, that fake authenticity dated really quickly. Do you remember U2 and how they got styled for the cover of The Joshua Tree? On the contrary, eighties pop music looks authentically dated . . . therefore it is indeed authentic. I think it’s quite funny that pop, by not claiming to be authentic, is so much more authentic. It has a freshness, an easiness, a naturalness about it and a bit of glamour. Pop has something that people in the street are genuinely into.

Only that you, in a recent interview with Spex magazine, said that “pop is surface”.

NT: A revealing surface, yes. But the point I want to stress is slightly different. The war between the fake authenticity of rock and the real authenticity of pop was sort of won by pop. But it could be un-won by a rock fightback in the future. For the moment, pop is the winner. Anything can be pop nowadays. We live in a pop world now—which means that everything is a question of style. Whenever a pop star shows humility, emotions or humanitarian engagement—this seems to be a style decision. I can’t decide whether they are sincere or not. I can’t tell if Lady Gaga is sincere when she calls her fans “my little monsters”.

CL: We call ours “our little pets”.

NT: Is it patronizing or is it friendly? I really can’t work it out. But we have to give her credit for many things. She does it her way.

Despite obviously being a pop record, Elysium sounds very different to anything you’ve done before. It sounds like you’ve listened to a lot of sentimental Hollywood musical scores from past decades—and pitched them down. You hear a lot of old-fashioned string arrangements, orchestra and vocal ensembles.

NT: You know we’ve always primarily seen ourselves as songwriters. That’s the foundation of it all. This time, we considered making an album that was in one mood all the way through. I’m talking of a musical mood. We wanted the songs to be slower, more reflective, beautiful and with more sub-bass. And this is why we decided to go to Los Angeles and to work with Andrew Dawson. We knew that we’d get the backing vocals there because the city has a long tradition of professional vocal ensembles and it was clear to us from the beginning that we wanted that on many of the new songs. Elysium is different to the albums we’ve made before. For instance, some of the new songs don’t have a middle eight, with the notable exception of “Winner”, which has one of the strongest middle eights we have ever written. The majority of the new songs have a simpler structure though.

What about the late Pet Shop Boys’ use of harmonies?

NT: If you listen to the first Pet Shop Boys album Please—and I think I’m right in saying this—you will find not a single vocal harmony. And on our second album Actually, the only vocal harmonies were made by producer Stephen Hague putting my voice through a machine. And then, when Trevor Horn comes along with “Left To My Own Devices”, he gets me to sing vocal harmonies on the chorus. As time has come along, I do more and more vocal harmonies.

CL: This time we worked with Sonos as our backing singers. They are a harmony group from Los Angeles.

NT: They’re a quintet from Los Angeles who performs concerts a cappella with effects pedals to change the sound of their voices. They, for instance, sing on our new song “Ego Music”. But we worked with the Waters Family too, who sing on eight tracks of the new album. They have this incredibly smooth sound—which is a very Los Angeles thing to get. We don’t have the same thing in Britain. We wanted this smoothness and elegance. That’s why we went to Los Angeles. You know, in America they have super-professionalism. In Britain we have great ideas. But it’s always about style. In America they have the professionalism of Barbra Streisand and Aretha Franklin. In Britain we have David Bowie, Mick Jagger and The Beatles. That’s why we approached Andrew Dawson who had worked on the last few Kanye West albums. The electronic sound of 808s & Heartbreak appealed to us a lot. It’s sparse, spare and sort of melancholic with all this aching and all this incredible bass. When we were writing “Invisible” that particular Kanye West sound seemed like a reference point. And that’s why we approached Andrew Dawson. And the first thing Andrew Dawson did was delete things, take things out. We were pushing him to put them back in, but he was very resistant. He was very polite and persistent so he succeeded. As a result, the record became simpler and more elegant. And it has a lot of bass while it’s refined to its essentials. To my ears, Elysium is a very warm-sounding record. As opposed to its predecessor Yes which was a very compressed-sounding record, very MP3-ish.

CL: I noticed that Andrew never left the studio.

NT: He probably just had such a strong idea of how the record should sound like.

What about you?

NT: Well, when we arrive at a studio, we give the producer so much to work with that we can easily leave the studio for a while. Our songs are always demoed to a very high level. It’s actually quite difficult to live up to the rough mixes that we bring with us. The job of the producer is to refine it and to make it better.

CL: I imagine someone like Kanye writes the songs in the studio instead of demoing them.

NT: I think maybe he does. I don’t actually know. But Andrew pointed out something that almost nobody seems to have noticed before. Kanye West often “vibes out” vocals, as we say. To “vibe out” means that from time to time you sing or rap little meaningless gobbledygook syllables that sound good but are meaningless. And Kanye sometimes leaves them in because they sound good—even if they’re pure nonsense. It’s amazing that no one really ever points this out. By the way: that is pop, because it is as much about effect as it is about meaning. I’m sure Andy Warhol would approve of that.

When you did Yesyou’ve worked together with a team of producers called Xenomania. You mentioned other producers such as Trevor Horn, Stephen Hague and Andrew Dawson. Why do you always seem to seek out a new producer instead of teaming up with someone for a longer period of time?

CL: There is definitely a hunger to seek out ways of doing things differently. It’s a fascinating learning process to see how other people do things. That’s also one of the reasons why we do cover versions. We want to see how songs work, and you learn it best by playing a song yourself.

NT: I would sometimes tell Andrew Dawson: “If you were Trevor Horn you’d be doing this now.” Or “Trevor would put a choir on it.”

Didn’t this annoy him?

NT: No. Once he even asked me what Trevor would have done in a certain situation.

And what did you tell him?

NT: Record someone jumping into a swimming pool and use it as the snare.

CL: Nobody works like that anymore. It’s of course a problem of cut-down budgets. In the old days, rock groups used to hire a studio as a lockout for more than a year. They were allowed to experiment. They could take a track down a road and see if it worked. If it was a dead end they could come back and try again. It’s no comparison to sitting at home on your computer and trying out all the plug-ins you’ve downloaded. Experimenting in a studio has become something of a luxury nowadays.

NT: But to be really commercial can mean to produce something fresh. Commercial music nowadays can be quite experimental. Actually, producing Elysium was quite an expensive process, too. It involved getting an orchestra, renting Capitol Studios in Los Angeles and very expensive backing singers. But of course, every experiment that you ever try out at the end has to still sound like the Pet Shop Boys. You want to keep the character.

In the Fall 2011 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine Brian Eno said, “You see it over and over again that good artists end up com-ing back to the same ideas they’ve always worked with.”

NT: Brian Eno works with different rock bands and different projects. We work with different producers as we have different projects. And of all these things you learn from and then move for- ward to the next thing. And it’s also the case that when you’ve done something you don’t want to do something like it next. You want to do it different, but not entirely. I’ve always been suspicious of people who jump genres. Look at Blur. First they were the English Blur. And then suddenly they were an American slacker band. How can you be both of those? Nothing against Damon Albarn—he is a talented musician and he is good at that genre-hopping. I agree with Brian Eno. You develop by doing the same thing over and over again, but always a bit differently. I’d say over the course of the years we have learned more about what we do. Continuity allowed us to have become more sophisticated with Elysium.

You are releasing an instrumental version of Elysium as well. Why that?

NT:We just liked the way the songs sounded without me singing on them. Sterling Sound mastered the instrumentals and sent them to us for approval. Listening to the instrumentals, I fell in love with them. And as a matter of fact, it was an easy way to have an entire bonus album that you can offer. It’s probably our first chill-out album. For several days I only played the instrumentals. I like them as much as the proper album. So we suggested to EMI to release it as a bonus CD for an extended edition of the album. And last but not least it is our first karaoke album.

CL: People will be able to sing along to it on YouTube.

NT: I can’t wait for the people who start to rap on it and put it online. Actually I caught myself thinking of other words that I could sing to these songs while listening to it.

CL: It would be interesting to write new songs on existing ones. We could call the albums Actually 2.0 or Yes 2.0 . . .

Has anyone of your status done such a thing before?

CL: I don’t know.

NT: I don’t think so. It’s funny because during the recording process you often change the lyrics of a song or you use the middle eight of one song in another one instead. “Winner” was a song that went through such a process.

The release date of “Winner” was perfectly synchronized with the kick-off of the London Olympics—where you also presented the song for the first time live. Did you write it for the Olympics?

NT: No, we didn’t. The idea for “Winner” came when we were on tour with Take That. Every night we’d leave the stadium while 70,000 or 80,000 people were going berserk to Take That singing, “Today this could be the greatest day of our lives”. And Chris said, “We have to write a mid-tempo anthem.”

CL: We’ve never done it before.

NT: We were talking about anthems in our hotel in Manchester. We were discussing “We Are the Champions” by Queen—and I’ve always hated the line “No time for losers”.

Didn’t Freddie Mercury sing the very line at Live Aid, too?

NT: He did, yes.

CL: That wasn’t right.

NT: And to make this conversation come full circle, Tony Blair played this song at his election party. I couldn’t believe that the members of New Labour could sing along to this line . . . It seemed so ridiculous.

CL: Let’s face it: A triumph never lasts very long.

NT: We are already halfway through the chorus and the triumph is already a memory. That’s the tricky thing with triumphs: As soon as you realize you have been triumphant, that moment is already over. You go on stage, you make your Oscar speech, and then realize it’s already over. Unless you happen to be Meryl Streep. And of course, you have to deal with all the fallout from then on. But that’s another story. ~

Published October 14, 2012.