Art Collection Telekom Presents Radenko Milak on the Allure of Disaster

In celebration of the Art Collection Telekom exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope, EB.net will roll out a series of seven short interviews with contemporary artists from Eastern Europe. They’ll all appear at the exhibit, which features a selection of works from Art Collection Telekom artists in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Fragile Sense of Hope opens at Berlin’s me Collectors Room/Stiftung Olbricht October 10 and ends November 23.

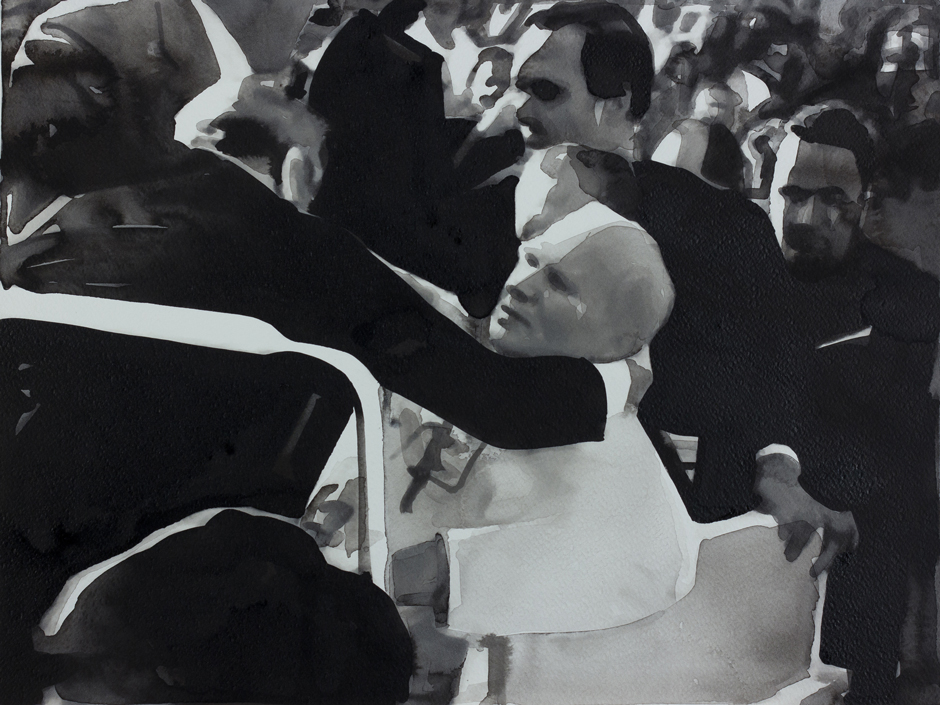

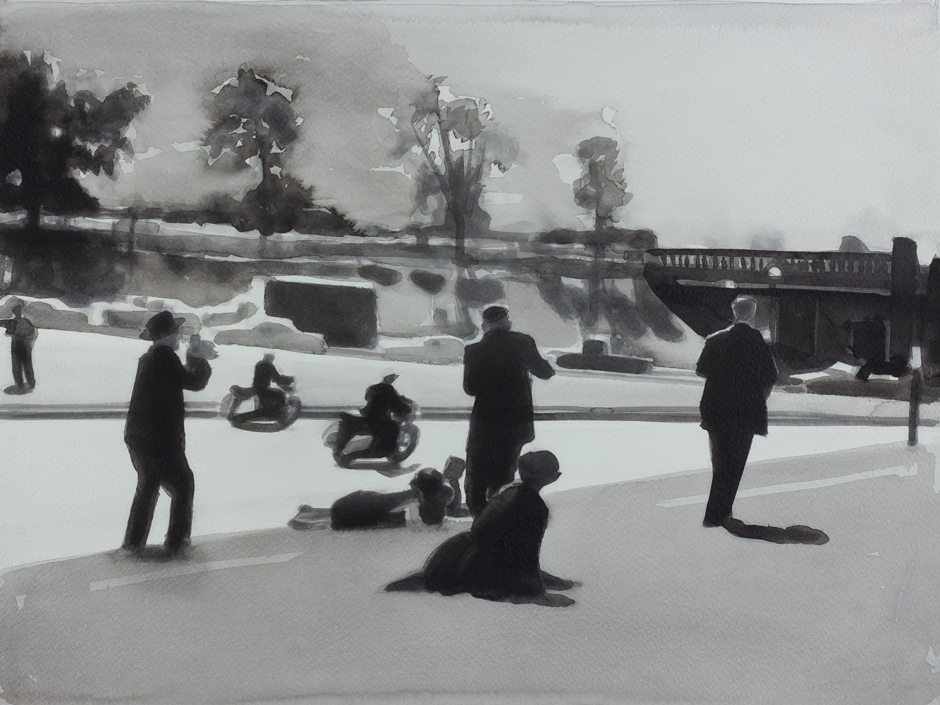

For decades, Bosnian artist Radenko Milak has interrogated the notion of private and public memory through the medium of painting. Using mostly watercolor to “translate” photographs from politically-charged situations, Milak questions the visual presentation of, amongst other things, the wars which have dominated his country’s history. In 2013, the artist completed a series of watercolors called 365 (Images Of Time), in which the painter re-created an image historically significant events that occurred on the same day he painted each image. Some of the pieces from the series will be exhibited at the Art Collection Telekom, and a major exhibition of his work opens at the Kunsthalle Darmstadt on the 16th of November, 2014. His works will also be on display at the Cologne gallery Priska Pasquer starting November 6.

From 2010 to 2012, you painted a series of watercolor pieces titled “What else did you see? I couldn’t see everything!” You copied photos by Ron Haviv, an American war photographer who documented combat in the city of Bijeljina in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1992.

Yes, that was during the initial phase of the war in former Yugoslavia. I did 24 of those watercolor paintings, and each of them displayed a cruelty of war. I was completely fascinated by these photos in a dark, schizophrenic way. I mean, these photos showed soldiers kicking defenseless elderly women in the face and other horrific scenes. But at the same time, these pictures seem to show very parenthetic situations. Horrible things happen in war, and this one took place right in front of my door, in my home country. It was unbelievable. I was 12 years old when the war started. But to say this very clearly: I wasn’t copying when I painted watercolor versions of Haviv’s photos. My paintings are new originals that explicitly reference Haviv’s photos, but they’re not copies. Maybe they are translations. Painting them was like studying and translating them very intensely.

After the war paintings, you started your 365 (Images of Time) project, a very sophisticated and diary-like series of 365 pictures that displays one historic event for each day of the year. You did this project in 2013 and focused on events in the 20th and the 21st century.

And again, I used watercolor in the same manner as I did for the “What else did you see?” project. Two things for me were fundamental. First, for me as a painter, it was a daily exercise in using different shades of black pigments on white paper to create a series of pictures that’d expand an otherwise simple conceptual idea. Second, I had to learn that the research part of the project became much more time-consuming than actually painting a picture every day.

- Photo credit: Florie Berger

Why black and white?

For me, it’s a minimalistic way of expressing explicit, unambiguous content. I always use the same white paper and the same black pigments. When done in the right way, watercolor paintings can look pretty similar to black and white photography. And, of course, by treating every painting the same way—both in terms of format and color —I synchronized the whole body of work. You immediately realize that this is a series of similar, but different paintings.

And there is yet another very important common thread in my 365 (Images of Time): I based every single picture on an existing source. The sources were documentary photographs, newspaper photographs and historic paintings. I basically eliminated my own imagination in favor of historical facts, and I spent a lot of time every day researching details about the subject I picked.

Was it always obvious which event to pick and to connect to any given day?

No, no! That was the most difficult part.

I thought the most difficult part was the act of painting.

No. I studied at the art academy in Banja Luca and Beograd—you learn valuable things there. You learn how to pay attention to detail, which is very important if you want to emulate a photo with watercolor and to translate it into a painting. Even though sometimes it’s really difficult to control the water and the pigment when you’re painting with watercolor, the difficult part was making the right decision regarding the event I would paint.

How would you know you had made the right decision?

I always tried to find an event that triggers both the collective and the personal memory. So, for instance, I used Mickey Mouse as the motif for January 13, 1930, which was Mickey’s first appearance in a comic strip. Or, take November 16, 2000: Bill Clinton becomes the first American president to visit Vietnam since the end of the war in 1975. Sometimes, it was very clear which historical event I’d link to any given day. Of course, I painted the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, as well as the attempted assassination of Pope John Paul II on May 13, 1981 in Rome. These two were obvious choices, but sometimes, I had a vast variety of choices. Intuition is very important in those cases. Only by following my own erratic instinct, my personality would rub off on the project.

I noticed a certain fascination for catastrophes.

You’re absolutely right; I’m obsessed with catastrophes. We had a war in Bosnia, and I think that the 20th century has been a century of wars, assassinations, and catastrophes. Of course, other centuries have had their wars, assassinations, and catastrophes as well, but they hadn’t yet invented photography or cinema. Mass media has changed everything in terms of perception—the 20th century became the century of collective memory.

Apart from that, I’ve read a lot of Paul Virilio’s writings. Basically, he believes that technology and accidents cannot exist without each other. There wouldn’t be a concept of an aircraft without the idea of a potential plane crash. At the same time, he claims that we’re losing our relationship with real space and real time because we rely on television and the Internet. Both concepts are present in my work. The Hindenburg disaster on May 6, 1937 is the mother of all modern catastrophes: the German zeppelin caught fire while attempting to dock at Lakehurst, New Jersey, and was destroyed within a minute. 36 people died, but without photos or footage, it’d never become that iconic. I feel attracted by photos of iconic disasters.

I was also fascinated by the Chernobyl meltdown. I tried to balance my fascination with man-made catastrophes by including portraits of important philosophers or politicians or artists or cartoon characters, like Mickey Mouse and Tin Tin. I belong to a generation that grew up with photography. And not only that—for the first time in history, all this information and all these photographs are connected through the Internet. All this is available within a split second. My work is also about the availability of images and information as well as the simultaneity of the non-simultaneous. The Internet has become our common memory.

You also painted Martin Luther, who was never photographed.

Photography was invented some 150 years ago, and that’s why I focused on that period. But paintings of Martin Luther do exist—they’re documentary paintings. I translated a famous painting by Lucas Cranach into my work. The same counts for Columbus and the discovery of America. When I’d notice that a certain person had been born or had died at a certain day, I’d sometimes opt for the portrait.

For instance, I’m a big fan of Klaus Kinski. I think he’s one of the best German actors of all time, but I only used images that already existed. Technically speaking, I used the same method as with the photographs: I transferred an image from one medium into another. There even was a moment when I asked myself how the project would have looked like if I had painted only portraits.

Are you as fascinated with dry historical facts as you are obsessed with catastrophes?

I come from a country that looks back at a lot of fake history—you’d find incorrect historical facts in schoolbooks. Socialist propaganda played a big role in my country. Relying only on historical facts and not commenting them seems to be an appropriate way of dealing with history.

Did you literally want to paint a map of the world?

This is a difficult question for me to answer. It’s difficult to explain my personal vision. I’d say that I wanted to write a diary for one year, without writing a single word that comes from me. Of course, I knew of many others who did journalistic projects before me, most notably Jonas Mekas—but I didn’t study them.

The most important observer of my project probably was León Krempel, who used to be a curator at Haus der Kunst in Munich and is now the director of Kunsthalle Darmstadt, where he’ll exhibit my 365 (Images of Time) series in November. During 2013, when I was painting and researching on a daily basis, we were in a constant dialogue. I’d send him a photo of my watercolor painting of the day via email, and he’d write a text about that picture. I always decided what to paint, but he’d always comment on it.

So, after a while this project became a ritual for you.

Yes, of course. You must not forget that it’s not easy to paint every day! Not for me, and not for any other artist, I suppose. But since it was my daily ritual, I had to stick to it. I had to continue.

How would you describe your daily routine?

Usually, I’d have what you might call a “normal day.” But in the late afternoon I’d continue where I stopped the day before, so I’d start researching various events that’d match with the day, and then decide which one I’d like to paint. Once I found a photo that really touched me, the process of painting it was the smallest part of the equation. That would take half an hour or maybe two hours. After I finished painting, I would photograph it and send it to León. Thanks to my project, my days were pretty structured.

To me, your paintings evoke an atmosphere that often reminds me of the aesthetics of film noir.

You’re absolutely right. My paintings recall the atmosphere of the black and white movies from the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. I’m an expert of Yugoslavian black and white movies from the 1960s. These are very minimalistic, often very political movies, and I’m really obsessed by movies from those decades.

Generally speaking, black and white is more abstract than color. When I went to the cinema in the eighties and nineties, I was more or less forced to always watch color movies. I started to envy the generations before me, because they were limited to watching black and white movies, and I thought they must have had a more abstract and surreal experience. Nowadays, only the Hungarian director Béla Tarr comes to mind. His movies summon the ghost of abstraction even nowadays. It’s a pity that Andrey Tarkovsky died so young! He did mostly film in color, but he had an incredible level of abstraction in his framing. As a result, all these films that I am talking about have a strong atmosphere, and I wanted to capture that atmosphere.

How important is the photorealistic style you are painting in?

I loved it from the beginning. It was my childhood obsession to paint things as realistic as possible. In our academy, I started to study the old masters, from the renaissance to the 20th century, because I was so fascinated by their realistic and precise style. I love Gerhard Richter, William Kentrdige and Sigmar Polke. But unlike them, I focused on watercolor, and this forced me to invent and to perfect my own technique.

It’s very difficult to be original nowadays, but I see myself in the great timeline of painters. Every painter has to face the fact that he or she is just the last link in a chain that is more than two thousand years old. I could spend hours gazing at a Vermeer painting! Standing in front of a real painting is a completely different experience than seeing a photographic reproduction.

In the last issue of Electronic Beats Magazine, we featured an interview with Raymond Pettibon, who sees himself in the tradition of Goya and his cycle of etchings titled “Desastros della Guerra.” Wasn’t Goya also something like the prototypical war photographer, except that he substituted the camera with etchings?

I spent a lot of time researching his work. I really think that he was a documentary painter of his time. Without him, we wouldn’t have a clear idea of what was really happening then. He was forced to see nature and real people as his motifs. Nowadays, a painter is not limited to what he sees in front of his eyes. If I want to put reality on the paper, I can also use a photograph or the Internet as a starting point. And before that there were libraries and archives. But the Internet beats them all, because it reminds us that we cannot escape from disaster.

Radenko Milak’s work will be featured at the Art Collection Telekom exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope. Click here to read more interviews in the series.

Published October 22, 2014. Words by Max Dax.