Art Collection Telekom Presents Şükran Moral on the Power of Provocation

In anticipation of the Art Collection Telekom exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope, EB.net will roll out a series of seven short interviews with contemporary artists from Eastern Europe. They’ll all appear at the exhibit, which features a selection of works from Art Collection Telekom artists in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Fragile Sense of Hope opens at Berlin’s me Collectors Room/Stiftung Olbricht October 10 and ends November 23.

Şükran Moral has made a career and a life out of provocation. She’s incited her deepest fears and other peoples’ hatred with controversial performances and video pieces, which have involved acts like public sex and self-mutilation. After being expelled from Italy and driven out of Turkey, she’s returned to both countries and now splits her time between Rome and Istanbul. Max Dax spoke with the challenging artist about the power of provocation and the role of women in Turkish society.

Hey Şükran, we’re currently chatting via Skype, so I’m wondering where you are right now.

I used to live in Rome, but in the last five years, I’ve spent more time in Istanbul—and currently, I’m right there.

Why did you leave Rome?

I never actually left Rome, I’ve just spent most of my time in Istanbul over the past couple of years. In 2010, I received many death threats in Istanbul because of my performance “Amemus,” which is the ultimate negative reaction to my work. For my own security, I moved back to Rome for a year and couldn’t come back to Istanbul. Now, my life is back and forth between Rome and Istanbul.

That’s serious. “Amemus” was a performance that you did in Istanbul, at the Casa dell’Arte, right? What happened?

Back then, I had an exhibition at the Casa dell’Arte, which would later become the Galeri Zilberman in Istanbul. There, I did a performance where I would make love with another woman. Obviously, this was provocative to many Turkish men. Turkey is a very religious and patriarchal country.

That wasn’t the first time that you provoked people. Years ago, you filmed one of your performances and titled it “Bordello,” meaning “brothel.” The video will be part of the Fragile Sense of Hope exhibition in Berlin. Can you tell me why it is so important to confront people—or, more precisely: to confront men?

“Bordello” was a commissioned performance piece for the fifth International Istanbul Biennal in 1997. For me, it was very important to leave an impression there. The years prior to that date marked a very difficult period in my life. In 1994, I tragically lost both my parents, and in the same year, I got expelled from Italy. I changed; I became somebody slightly different. I was a woman, I was an artist, but I was from Turkey.

I always believed something like that wouldn’t happen to an artist—I really believed that the concept of “being an artist” would make me a persona grata. But I realized that, to the police, I was just an illegal foreigner with no visa, not a woman or an artist or a human being. I was regularly studying at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome, and I was doing a lot of performances all around Italy, so my expulsion was actually illegal. For the following two years, I lived in the underground with an illegal status. So, in hindsight, I can say that I stopped to be an idealist. And I remember very well how this expulsion changed my whole perception of the world.

You felt rejected?

Yes, and because of that rejection I finally became a true artist.

How did you realize this transformation?

I quite consciously and suddenly chose that my answers to everything that ever happens to me should always be artistic. I would call this a transformation. I strongly believe in the power of creativity. I think that you can change a lot as an artist, and I would call art a stronger currency than weapons and money.

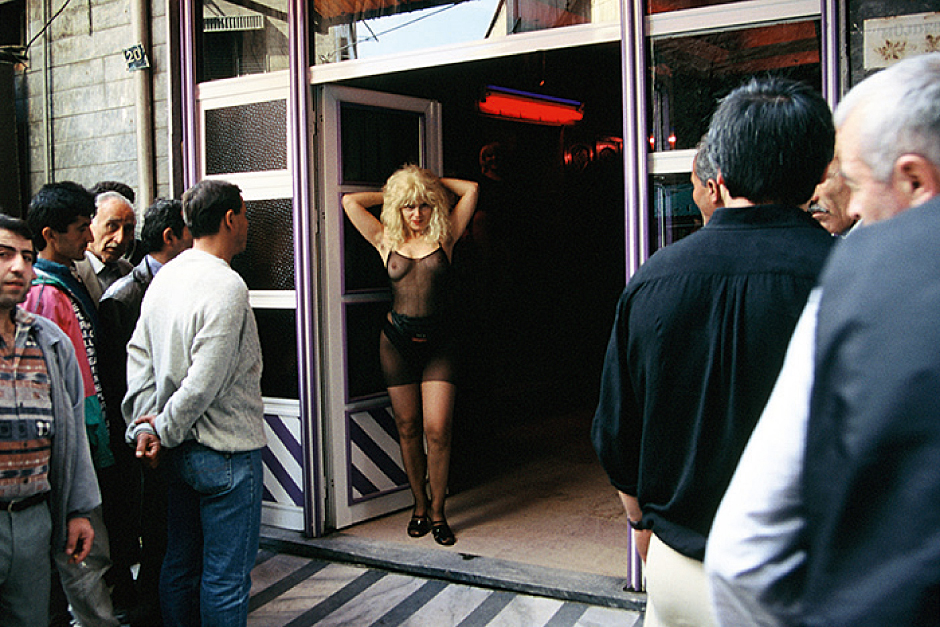

Coming back to “Bordello”—how does this performance fit into the equation? You dressed up like a prostitute and walked right into an Istanbul brothel. You had two signs that you would hold up in the air: “For Sale” and “Art Museum.” Didn’t you even rename the brothel into “Museum of Art”?

Basically, the invitation to participate at the Istanbul Biennal gave me a second chance. Coming back to Istanbul was a very emotional moment, and I tried to make a special performance. In fact, I did five different performances, two of which became quite well-known: “Hamam” and “Bordello.”

All five performances dealt with things that have haunted me for years—for instance, my parents would always threaten me with the phrase that I would “end up like a whore in a brothel” if I didn’t do as they said. Doing the “Bordello” performance in Yüksek Kaldirim in Istanbul was like diving straight into the pain. Also, the other performances dealt with my fears, such as getting admitted into a mental hospital to shut me away from society. And yet, another performance was about being thrown into prison—which, by the way, can happen to anybody at any time in modern Turkey. The whole system has a very strong Kafka-esque side. Everything bad can happen to you during a day.

So, basically, you dared your primal fears.

Exactly. I wanted to discover what’s lying behind the surface of my deepest fears.

The German BILD tabloid has called you “Turkey’s most courageous artist.”

The tabloids always call me stuff like that—but I’ve never considered my performances as courageous. I don’t even think while I’m doing performances. For me, the only important thing is the conceptual aspect within. Being courageous or not doesn’t matter, as it’s the concept is always most important. For the “Bordello” performance I transformed into a prostitute, but I also transformed the brothel into a symbol for the art market. I think that all the big institutions in the art world are like giant-sized brothels.

You didn’t do the performance alone—there was also a photographer and a cameraman present.

There were three of us. At the brothel, some of the johns would jostle me around, and they’d also bump against the cameraman. If you watch the video, you’ll notice that it is quite shaky, not because we weren’t professional—it’s because we got pushed around. We used a huge Betacam back then. Nowadays, you could do the same with your smartphone, but in 1997, we embraced the heavy reactions of the men against the presence of the camera.

Don’t forget that the whole performance was targeted against Turkish macho behavior. We wanted to deal with it ironically. I mean, in Turkish society, women are considered virgins until they get married, while men visit brothels constantly. It’s quite a backward and medieval understanding of the role of women in society. Men are allowed to have fun; women have to deliver.

On your website, you welcome the visitor with the words “Resist Turkey!”

In the last year, we had the biggest demonstrations ever in Turkey. Some of the protesters invited me to do a performance as part of the demonstrations, so on June 14, I did a performance in Gezi park in which I cut myself. I cut the letter “A” on my belly with a razor blade—“A” as in “anarchy.” That was the performance.

Of course, I know about all the performances in history in which artists have already cut themselves on purpose—so why should I? Of course, I know that this is a topos in the history of art since the seventies. This is important. I didn’t want to repeat something others have successfully performed before me. But I think that prejudices come from the belly, and that’s why I cut the letter “A” there.

Şükran Moral’s work will be featured at the Art Collection Telekom exhibition Fragile Sense of Hope. Click here to read more interviews in the series.

Published October 01, 2014. Words by Max Dax.