Behind Bars: Meet The Georgian Techno Producer Making Music From Prison

Michail Todua, now 33, has been in prison for five years. A Georgian native who grew up in the capital city of Tbilisi, he spent his life as a DJ and party promoter before being randomly stopped on the street and taken into a local police station for drug testing. Todua, without access to legal or financial help, was incarcerated at the Tbilisi Ministry of Corrections and sentenced to nine years. And while he’s now successfully making and releasing music from within the strict confines of his jail cell, many thousands of people who have been imprisoned under similar circumstances have not been granted the same degree of welfare.

Since the early 2000s—and the implementation of a new and conservative social policy—Todua’s story is one of thousands that have taken root. Most of those who have fallen victim to the swell in arrests have been forced to give up homes, families and physical possessions in addition to serving unjustifiable jail times. The growth in the number of these incarcerations in recent years, however, has fomented discontent within the city’s younger—and more liberal-leaning—generations, and sown the seeds for fledgling movements fighting for advocacy and political reform.

Many young people in Tbilisi describe the city’s sociopolitical landscape in the same way: as being stuck between the Soviet era and the period that’s followed it. A more accurate depiction of the Georgian capital’s current climate, however, may not be of being stuck, but of being suspended, like a buoy, within discordant social currents and rapidly changing political tides.

Long regarded as an affluent metropolis within the Eastern European and Central Asian region, Tbilisi was absorbed into the emerging Soviet Union in 1921, where it remained until its independence in 1991. Like many of its post-Soviet neighbors, the years of violent fighting that eventually ended in its secession have since given rise to a myriad of domestic instabilities, a shifting political landscape, economic fragility and a dearth of social institutions in the wake of domestic struggles for political power. In the 21st century, then, what has survived are deeply-entrenched conservative attitudes that stem from an antiquated—and predominantly Russian Orthodox—government, and a new generation of young people seeking change. The most earnest of the latter’s pursuits is the country’s attitude towards drug policy, where stringent laws have led to the incarceration of more than 20,000 people over the last eleven years.

“The zero-tolerance policy towards drug use started in 2006,” David Subeliani, one of the leaders of the Tbilisi-based activist organization White Noise, says over a coffee at a downtown Tbilisi restaurant. “The post-Soviet administration that came into power in 2012 said, ‘We’re going to change everything that the old government was doing wrong.’ But then that year when they came into power, they took 60,000 people for testing. 60,000 is more than two percent of the adult population.” Those who test positive for traces of controlled substances are criminalized, fined under plea agreements for tens of thousands of dollars—and put in jail for sentences that range from eight to twenty years. People convicted of rape and terrorism, by contrast, are sentenced to only four and six years, respectively. And despite recent pushes for progress, the swirling eddy of outmoded political directives, youth-led liberal policy campaigns and residual economic and social turmoil have left the city, and the country, in a place where many people at the margins are continuing to slip through the cracks. Frequent and random drug testing on the Tbilisi streets continues to be commonplace, and the young men who are frequently targeted by the police are inordinately more likely to be lower-class.

According to Subeliani and other members of Tbilisi’s burgeoning activist community, these shifts towards more conservative policies aren’t only an outgrowth of traditional social mores, but of a more insidious financial incentive to fund the city’s policing institutions and to control the population. “The government is getting however many millions per year from fining people for drug use,” says Sergi Gvarjaladze, the founder of the Georgian electronic music collective Electronauts. “It’s an income on their balance sheet, so once that income is cut and they can’t extract money out of these policies, those policies won’t matter as much anymore. And then they’ll have 40,000 employees who also won’t be needed.” The government-led effort to “clean up” the city’s drug-using population has not only led to mass jail sentences, but to the widespread demonization of drug users and the dismissal of the critical kinds of rehabilitative social services that exist in many other parts of the world.

Because Georgia’s strict drug laws fail to draw distinctions between types and amounts of illegal psychoactive substances, a person caught with a small amount of MDMA for personal use—as was the case for Michail Todua—is sentenced to the same amount of jail time as a person caught with an amount intended for large scale distribution. Subsequent jail time can range from anywhere between eight and twenty years. And while Todua’s case is just one of a multitude that have arisen over the past decade, his close connection to the city’s creative scene hit the local community particularly hard. Previously a linchpin of the city’s underground music scene, Todua was forced to shift his focus to production and music creation in the years following his incarceration.

His in-jail music studio lies behind the Tbilisi Ministry of Corrections’ high, barbed wire-trimmed white walls, cadre of machine gun-carrying guards and nearly two-hour-long security control. The makeshift 10-square-meter workshop is situated on the third story of a building that could pass as an elementary school; its long, empty hallways are filled with windowed doors that look into rows of desks, inmate-crafted pottery projects and white fluorescent-lit classrooms. Todua’s space contains only a table littered with an old desktop PC, various small synthesizers and a collection of traditional Georgian folk music instruments that he uses to sample, and sometimes to play.

“When I came here and realized that I couldn’t DJ, I thought, ‘Ok, I can’t live without music,” Todua explains through a Georgian translator. After two years spent trying to decide how to execute his new creative direction, he advised his wife to sell his car and purchase a small selection of music gear. And while the corrections facility eventually also allowed him a laptop and headphones, without access to the Internet—and the online tutorials, videos and demonstrations that it provides—the road to music production was long and frustrating. “I had never made music before, and I wanted to improve, but without access to the outside world it was so hard,” he says. After a depressive episode spent navigating the confines of his new living and working situation, he succeeded in beginning to make tracks, and then, in giving them to his friends to listen to. For Todua, making music not only provided him with a new creative outlet, but with a renewed sense of freedom. “Once I figured out how to produce while being in jail, it became the only way to make me happy,” he recalls. “When I write music, it’s like I’m not here.”

Over the course of ten years, Todua has evolved from a novice to a releasing musician, and has even scored a number of prison-produced plays. His first long player was a soundtrack to the 1954 television play 12 Angry Men, which was acted and performed by a group of Ministry of Corrections inmates. Following the success of this production, Todua began to collaborate with three other prisoners on reinterpretations of traditional Georgian folk music in which he, the electronic musician, remixed and re-conceptualized recordings completed with a singer, a guitarist and an accordion player.

His more recently-produced solo music, which he plays from his small studio monitors, is predominantly defined by its dark, swelling synth lines and industrial-limbed percussion. “Sometimes I try to make music that sounds happier or more melodic,” he explains over the thrumming bassline of a sinewy four-to-the-floor track. “But here, it’s impossible. When you’re caged in, everything that comes out of you sounds dark.” The four songs that he plays are colored with skittering drum lines and hues of dub not unlike the bewitching two-step-indebted psychedelia of Machinedrum’s Sepalcure project or the shadowy resonance of early Bonobo. His first official EP—whose tracks were disseminated to various labels by his wife—was released under the moniker Michailo this past February on the London-based label Login Records.

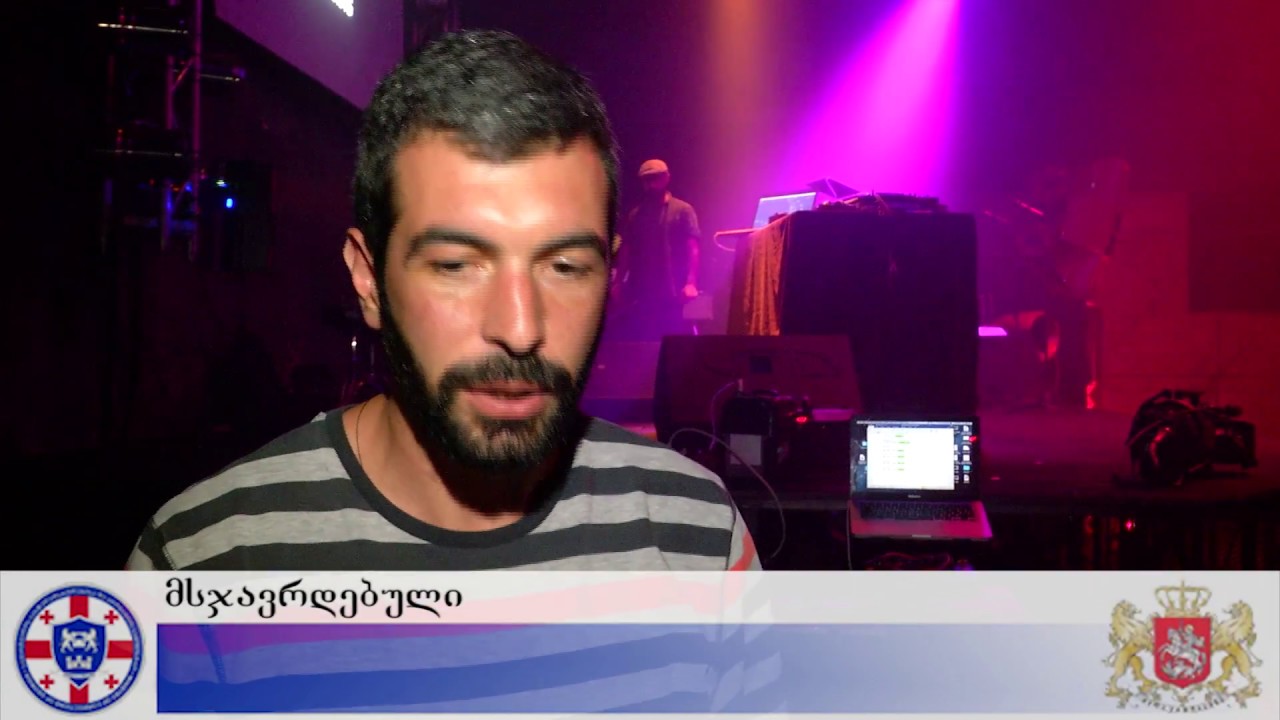

But perhaps one of his most outstanding accomplishment to date has been being booked to play a live performance at the 2017 Electronauts ceremony, an annual electronic music award that highlights the country’s rising techno talent. Todua came to perform accompanied by 15 prison guards who supervised him playing his performance from beside the stage before escorting him back to prison (which you can view in the video below). For Electronauts founder Sergi Gvarjaladze, the event was an important milestone in helping to reform the country’s strict laws by casting a light on one of its victims. Bringing Todua to play only five years before that, he says, would have been unimaginable. “Having the government support Michailo playing this show means that they recognize that they need this kind of good PR,” he says. “We were giving them good publicity, and I think that’s going to influence their relationship with Georgian society and the laws we’re trying to change.”

The inordinate constraints that Todua has been met with are representative of a larger trend in Georgian society, and within the creative community in particular. According to Gvarjaladze, there are more than 3,000 prisoners currently in the Tbilisi penitentiary system, many of whom were arrested for possessing negligible amounts of drugs, and some of whom have faced longer jail sentences than Todua’s—and sometimes even serving consecutive sentences. Todua’s story and ongoing connection with many of the advocacy groups on the outside, however, has helped to propel the growth of critical organizations like White Noise and Equality Movement, the largest LGBT organization in Georgia, that are fighting the city’s conservative legal standards.

The other significant contingent of young social advocates that have begun to examine Georgian policy issues under a critical light have come from the city’s nightlife institutions. The appearance of clubs like Khidi and Bassiani—which we reviewed shortly after its inauguration in 2014—are emblematic of a larger thrust towards liberal policies. “These places have become islands of freedom and love,” Gvarjaladze says. “They’re very important culturally and socially. They’re about freedom of expression, about fighting for the ability to be different.”

By providing an open platform for behaviors that have historically been vilified by the rest of Georgian society, the people running these venues hope that they can redefine attitudes beyond the nightlife space and influence policy on a government level. But Tato Getia, one of Bassiani club’s primary bookers, said that he and his friends championing these changes still face considerable obstacles from the city’s lawmakers. “They have a big campaign against us saying that the activist groups that we’re all involved in, like White Noise, are run by drug dealers,” he says over dinner. “The government here is just against any kind of growth. And at the end of the day, it’s not even about them being morally against drug use or liberal ideas, but about their need for control.” The zeitgeist among Getia and his colleagues, while optimistic, is judiciously cautious.

Clubs have become important in imbuing young Georgians with a renewed sense of cultural identity, but perhaps more significantly, in providing safe spaces where they can experiment with liberal attitudes nonexistent in mainstream society. The monthly queer party Horoom Nights that takes place at Bassiani is one important byproduct of these venues’ recent launch. And while gay nights in other cities are now relatively commonplace, in Georgia, where some 90 percent of the population has reported to polls that homosexuality is “never acceptable,” the cloak-and-dagger that these nights provide is essential.

“The appearance of spaces like Bassiani, where Horoom Nights takes place, has allowed for dark places to exist away from the public eye where gay culture can exist in private,” adds Levan Berianidze, a member of Equality Movement, and an organizer of the aforementioned monthly gay and queer party. These events are typically well-attended by members of Georgia’s NGO community—like White Noise—and allow for members of the city’s activist and civic sectors to come together within the sanctuary of a safe space. Parties like Horoom Nights, in turn, have been particularly constructive in giving birth to the city’s drug liberalization campaign. It’s a widely accepted fact within the nightlife community that drug use is more common within these contexts; the club owners’ aim is not to encourage it, but to destigmatize it.

According to William Dunbar, a Georgian-based journalist and the author of an article on Horoom Nights in The Calvert Journal, the confluence of these queer parties and the city’s advocacy groups has created a palpable sense of community and has been salient in driving paradigm shifts in social mores on a wide scale. “Horoom has become a symbol of just how far the country has come in the last few years,” he writes, “and its success is attributable to both the passion and drive of its organizers—both from the clubbing side and the NGO side—as well as the breakneck pace of change in Georgian society as a whole.” Work from people like Subeliani and Berianidze has ensured that the next generation is already growing up in a very different Georgia; and while parts of the government do still appeal to the country’s Orthodox base and the police still, largely, do not prioritize the needs of the city’s minorities, there is a feeling that a corner has been turned.

Todua’s case is one real and concrete example of the fruits of these undertakings. Upon this article’s writing, Todua’s early release from prison is being negotiated with the Georgian government. It’s anticipated that he will even be able to return to his wife and home at the end of May, and shortly afterwards, release a collaboration with a Berlin-based record label and play parties on the broader European stage.

His imprisonment, if anything, has only incited his inclination to produce music seriously. He’s currently working with his wife to build a bigger and better-equipped music studio that will be ready for him to use full-time upon his release. “Right now, I’m only allowed five hours a day here, and only for five days per week,” he says. “I can’t decide when I can be creative. And when I hear new music, it’s tracks that my friends choose for me and put on a USB. So I can’t listen to or look for music properly.” He looks forward to having a space of his own to work on music without the limitations, cameras and security restrictions that the last half-decade of his life have saddled him with. “I have many ideas of what I want to do after I get out,” he says. “But mostly, I want to travel. I want to walk everywhere and I want to play music.”

Is Todua’s case a bellwether for the liberalization of Georgian social policy? David Subeliani believes so, and he has a strategy in place to ensure more positive outcomes such as Michailo’s. “We have to maintain pressure over time so that we can prevent the kinds of arrests that are happening to thousands of people,” he says, and the best way to do so is to educate Georgia’s younger generation and to instill values that uphold social minorities’ rights, needs and place in a rapidly modernizing society. The vanguard of this advocacy-oriented sociopolitical movement, he assures, will continue to happen on Tbilisi’s street protests and dance floors. But to galvanize far-reaching changes and marshal significant and lasting improvements to the policies governing the creative community’s basic freedoms, there need to be efforts to disseminate tools throughout the community so that more citizens can become engaged in the conversation.

Subeliani, in his oversized orange sweatshirt, puka shell necklace and fraying yarn bracelets, is an image of quiet composure and peaceful conciliation. As he looks around the table at other members of the Bassiani and White Noise teams, all passing joints, laughing and sharing stories of resistance before courts, politicians and members of the police force, it’s difficult to believe that these are the Georgian youths who have struggled so vehemently against the local government’s iron-fisted pursuit of social control. But if the previous 12 years constitute Tbilisi’s long, cold night, then this particular group is heralding the moment when the radiator finally sputters to life, ushering in the country’s still and uncertain dawn. “We’re here to fight for a new and better world,” Subeliani says vigorously. “We’re not leaving anyone behind.”

Follow Michailo’s music on his SoundCloud page here and on his Facebook artist page here. To see more of Yacoub Chakarji’s photographs, visit his Instagram.

Read more: 9 synth artists who defined Eastern Europe’s post-Soviet sound

Published May 11, 2018. Words by Chloé Lula.