This Is What It Was Like To Live In One Of Those Legendary ’90s Berlin Art Squats

Activist and photographer Ben de Biel was there at the start: at Kunsthaus Tacheles, at I.M. Eimer, and as the founder of the (now closed) MARIA Club. Today, de Biel has moved on from organizing events and now works as the press relations officer for the Piraten Partei. In this monologue, part of a series of artists and other key cultural figures speaking openly about their artistic experience in the city, de Biel told us about his own Berlin experiment.

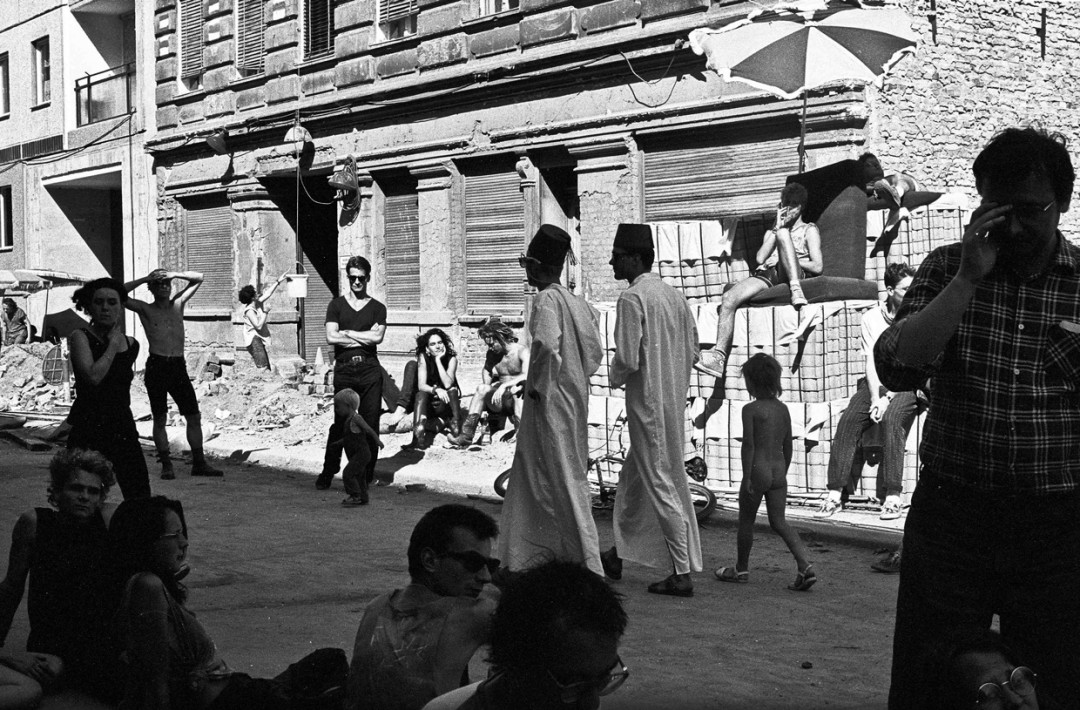

In February 1990, soon after the Wall came down, I went to check out the Berlin situation. There was still a border control for Western citizens and upon my entry, East Berlin seemed very strange to me. It was dark and at nights only every second street lantern would be lit, oozing dim, orange-colored rays. Some streets had no illumination at all. There were very few cars and nearly no people in the streets. Utterly spooky. Like in a Tarkovsky film. Like an abandoned city.

The city centre buildings were characterized by their emptiness, which the GDR government had obviously advanced in order to get rid of the decrepit Altbau houses. The Mitte neighborhood was especially empty—the administrative region wasn’t exactly where people wanted to live in the GDR, I assume. Others had escaped to the West before the fall of the Wall. The buildings were in a horrible state of decay with whole blocks between Torstraße, Oranienburger Straße and Rosenthaler Platz scheduled for demolition.

The Wydoks’, the prototype squat which had been squatted in 1990, was at Alte Schönhauser Straße 5 in Mitte. East Berliners from the music scene around bands like Freygang, Die Firma, ichfunktion and Feeling B started pro-squatting action right after the Wall came down. They knew about buildings that had been taken off the cadastre and were consigned to demolition. Those buildings were officially non-existent, which furthered the hope that one could stay there in peace for a bit. Empty buildings were there for the taking.

Efdemin’s “Transducer” video, featuring images of East Berlin in 1990.

In January 1990, some members of the original germ cell moved on to the I.M. Eimer building on Rosenthaler Straße 68. In February others took up residency at the former department store Tacheles, also in Mitte. The very building later to be known as Kunsthaus Tacheles had not been occupied yet, but people had immediately moved into the two adjacent houses.

The Tacheles building is an edificial icon. It remains a cultural landmark today, even though the artists were evicted for good in 2013. It’s Berlin’s first steel frame construction and back then, due to lack of experience with this kind of building, an excess of steel was used. The squatters knew the thing wouldn’t come down easily, that it would stand forever. The only problem was with the structural design, parts of the building had been demolished in the early eighties and they’d filled the cellar with water to prevent the street side building from tipping over. The Tacheles cellar was like a swimming pool, you could go deep sea diving. One Australian dude actually did that.

Up to the mid-nineties, there was a constant influx into Berlin, West Germans predominantly, but also people from Spain, the USA, Australia—everywhere. The intervals between my visits became shorter too. In April, some friends had already squatted a house on Kleine Hamburger Straße 5, directly in the city centre. Spring came and daylight was not as sparse as it had been when I visited in February. I started seeing things and realizing what I saw: something completely different from anything before. East Berlin seemed to hold the promise of immense possibility.

In the political sphere, the first six months of 1990 were spent discussing possible alternatives to the GDR system. The atmosphere was governed by a sense of departure from the past, but that changed quickly with Helmut Kohl doing his ‘Come to Daddy’ dance which limited the issues to currency union and reunification. In the following three months East Germans were busy discussing profit maximization in terms of finding as many friends and relatives to open up bank accounts to make use of the guaranteed 3000 Ostmark to Deutschmark exchange.

When, on July 1st, the Ostmark was exchanged for the Westmark, one third of the Eastern population left for a vacation, another third bought a car and the last third spent it on other stuff. There was an instant invasion of rickety old cars taking all the parking spaces—most of these cars were left to rot when they were no longer roadworthy. I myself was given two Trabant cars.

In September 1990, briefly before reunification, I moved to Berlin for good. I was immediately taken in at the Kleine Hamburger squat, given two rooms, a shared kitchen and shared bath: a symbiotic community of 12 in a beautiful and colourful squatted house. We decorated for comfort and for insulation. Once, the whole house was made into an exhibition: we printed posters, set up a bar in the court, cleaned everything up and had a lot of fun. Buses with tourists came by on their tour. At nights, we’d wait outside dark apartment buildings and watch; if we hadn’t seen any lights in an apartment for three days, we’d go in and have a look. Two apartments above what would later be the Friseur Club even had two working phones with open international lines, it must have been an office space. One could make phone calls to the US for free so we changed the locks and passed the keys onto people from Italy, Spain or the United States—whoever needed to make international calls. Then, one day, the phones were gone. Who knows who eventually paid the bill?

Until the mid-nineties, the streets were crammed with stuff. You could decorate your apartment with found objects and everything labelled ‘GDR’ was thrown into the streets. For every club, a GDR found object was the highlight of the décor—and everything you needed could be sourced from the streets. The only things paid for were screws, nails and cables, then all you had to do was rent a PA and record decks from West Berlin. The core of those early clubs was DJ, turntables, and drinks.

At first, the only place to go out to was Tacheles, where everyone would go for drinks and discussions but never for clubbing. The first bar was the Freudenhaus on Christinen Straße and the Kommandantur at Wasserturm Platz in Prenzlauer Berg. The very first club to open was Ständige Vertretung at Tacheles, which I soon got involved with. The story of Ständige Vertretung? Ok, here we have a door, there is a stairwell going down into rubble, we cleaned up and opened a club. It would be full of wildly dressed people with the dress code being subject to diverse factors. For example, the last furrier in Mitte had closed his business in the winter of 1990 or 1991—suddenly everyone was wearing fur coats. There was an air of the Neanderthal. You wouldn’t see platform heels or reflective vests at Ständige Vertretung, it was reigned by another kind of crazy, real crazy.

Soon, the first weekday bars would emerge alongside the first proper techno clubs Tresor and Planet. Renowned DJs like Clé, Dixon, Tanith, Kid Paul, and Dr. Motte would play those venues. Techno brought a new vibe and nicer, more open people who would take the more relaxed types of drugs. Speed and ecstasy were cheap, affordable to both the East and the West Berliners. No one has ever been beaten up on ecstasy, not even on speed. When you watch American television you get the impression that speed brings out the worst people. I never made that observation with the speed heads of the nineties. We never had any trouble at the club, making the evening a nice experience for everyone was part of the concept anyway. Everyone wanted to be family, to belong, and to experience something great together.

In 1990, a myriad of disengaged young people from East and West were meeting in Berlin. The baby-boom generation, probably the highest concentration of young people in one place that Germany had seen in decades. That led to music, drugs and sexual freedom. We would meet in clubs, not on the internet, and we were bringing sex out into the public sphere. Today you date online, and sites like YouPorn are giving the contemporary kid an idea about what fucking looks like. This wasn’t the case back then, we had to try it out and the soundtrack was techno.

Everyone touring Mitte would pass by Ständige Vertretung at one point. It was pretty difficult to get people from elsewhere into the club. With our Rare Groove evenings especially it got tricky, since we had black friends from the West who would’ve loved to come but didn’t dare go East, where it was dark and still latently fascist. We had a massive problem with Nazis in the city centre in those days.

Meanwhile, after the initial shopping frenzy had worn off, all the lights went out in the East and the liquidation of the GDR was at hand. Like the people disposing of their stuff in the streets earlier, the whole GDR to FRG transition left the Eastern economy up for grabs. Soon, every second person from the East was unemployed and broke. Job creation programs were put into place and a phenomenal amount of money was spent on welfare. Also, strange things started happening in Mitte. One time, when Dorothee Dubrau, municipal councillor for construction, was away on a vacation, a huge digger rammed an old building “by accident”. The Elektro Club was in that building and just shortly before, Mrs. Dubrau had decided in favor of the club and against new building activity. The two apartment houses next to Tacheles suffered a similar fate when, in 1992, the attic caught fire “all of a sudden”. All the tenants were evicted and the owner demolished the property.

In most cases, property rights of buildings weren’t resolved. Reassignment to the pre-GDR owners was being discussed and implemented. As soon as the owner of a building had been identified, it was up for sale. Investors bought property for very little money, Werner Düttmann, an architect from West Berlin for example, had subsequently bought Kleine Hamburger 5, Linienstraße 158 and half the street of houses. As soon as something was up for sale, he would buy it. Some gambled too high, expecting rents to rise more quickly. On Potsdamer Platz, investors speculated that within the next three years the rents would hit 100 Deutschmarks per square metre. That, of course, never happened.

I.M. Eimer on Rosenthaler Straße was one of those houses no longer registered in the cadastre. A faction of Easterners had founded the non-profit organization Operative Haltungskunst as I.M. Eimer’s administrative initiative. Between 1990 and 1991, the GDR secret police files were made open to the public, and this is when strong discord set in. Andrés’ file said something different from Tatjana’s file, but both were members of the same band, Freygang. I never really got the whole problem, but everyone was at odds with everyone. The Easterners were too busy throwing their respective pasts at each other, and so they shut the door.

In 1993, I.M. Eimer was re-opened by Peter Rampazzo, the last of the first generation of squatters. In the eighties Peter had fled the GDR, but he had come back after the fall of the Wall. New members joined and the first second generation person I knew was a guy who knew how to weld. I started recording tapes, and because there was no PA, we played them on a massive ghettoblaster in the café. Then, step by step, we rebuilt and decorated the premises. After a while, Spoon, who was the guitarist of a band called Kiss Freak Steven, brought some speakers he had found somewhere, and we built them into the floor.

For party events, we’d rent a PA. We tried to earn money for our own one by generating some income with the club, but money discussions would always take us to the next level. Everything professionalized instantly. We agreed to have a Saturday night program with a cover to save for the PA. Later, when we eventually bought the thing, it would be available to anyone in the house for free. However, this is when conflict arose. Peter was offended, because he had been overlooked, the decision made without him. When things came to a halt in 1997, we moved out, taking the PA with us.

After we had left I.M. Eimer, we wanted to reconvene someplace else. Hans and Maarten, two guys who had their workshop in the Eimer court, approached me saying that they had found somewhere interesting and didn’t I have some money to spend? I had, thanks to a little inheritance I hadn’t touched yet. And so, with these two and two others, we opened the first MARIA am Ostbahnhof.

The only people with money were my partner Hannes and myself, I bought everyone out who had contributed to buying the Eimer PA. Thomas brought furniture and interior decoration stuff. Everyone knew how to build things except me, but I knew the word ‘deadline’ and made the necessary phone calls and looked after the program. That was my job. This is how MARIA came about. MARIA am Ostbahnhof was the first club outside of Mitte but it has to be said, the building was phenomenally cool: the floor was made from polished granite, pillars all over, old woodworks and a pater noster lift. Not bad for a former post office! Berlin’s construction supervision authority declared the place fit for purpose. It took us three months until we opened, completely legal, and after three rent-free months, we paid five Deutschmark per square metre, approximately 6000 Deutschmarks in rent.

The program idea behind MARIA was to re-energise performance culture, which had been displaced by DJ culture. I had a live performer’s background with my band Elektronauten. At that time, club culture didn’t provide opportunity for people to play the bass or the guitar, or grab a microphone. We were out to change that. The first year at MARIA saw performers like the Nightline City Cruisers crew: Chilly Gonzales, then still under the ‘Wolf’ moniker, Raz Ohara, Robert Defcon and Dr. Phelbs. Every Wednesday, they would sit on the sofa smoking weed while combining electronic music with instruments, rap and singing. In the final days of Nightline City Cruisers, even Peaches joined the gang. At one of her first gigs at MARIA, she put a CD in her pants and went, “Come on, get the CD and it is yours!”. It took some encouragement until someone eventually dared to fish the disc out of her underwear. Today, no one would hesitate, but then there was a moment of real trepidation.

Business at MARIA was amazing from the start, much better than expected, anyway. With 300 people, the venue was sold out. It became evident that 300 people was a number we could reach easily with any of our programs. That made booking a pleasure and released a lot of energy. I didn’t really know myself why this was happening, I simply asked everyone I knew if they’d be up for doing something at MARIA. Suddenly, there were so many people I didn’t know but they introduced themselves and did their thing. Contrary to upscale venues like WMF, MARIA had always been a little scummy. We had hardcore porn posters by the toilets, but nobody minded. There was only one band who, in 2001, mocked our toilet decoration—they reaped boos and abuse from the audience. Everybody else loved it. The extent of the hedonism was such that everything was possible.

I was young and looking for adventure, but the established people asked for my portfolio and who the fuck I was anyway. This makes you wonder how long they expect you to wait until you get permission to do your thing; whose arse do you have to kiss and for how long? That was, of course, not an option, I would go my own way, and not waste time with the establishment. That was also my idea of ‘punk’. I simply liked doing it.

Read our evolving archive of Berlin’s musical history by visiting our Berlin Experiment page.

Published May 20, 2014. Words by robertdefcon.