Ben Frost Speaks to Richard Mosse— “Your work will be distilled into a plugin in Photoshop.”

Ben Frost in conversation with Richard Mosse.

In early 2012, the Australian-born, Iceland-based composer and expansively dynamic musician Ben Frost stumbled upon Infra, a book by Irish photographer Richard Mosse based on a series of photos Mosse had taken in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In creating the images, Mosse employed the discontinued military surveillance film Kodak Aerochrome, which sees infrared light and renders plant life a lurid shade of pink. After a lively email exchange, Mosse invited Frost to the Congo to provide a soundtrack for the next evolution of his Congolese work, the film installation The Enclave, which premiered at the Irish Pavilion of the 2013 Venice Biennale to much critical acclaim, not least for Frost’s soundtrack of field recordings from the Congo. Recently, Frost took time off his hectic touring schedule promoting his new album A U R O R A to meet up with Mosse at the artist’s studio in Berlin to talk about their respective work and future collaborations. The conversation was moderated by Lisa Blanning.

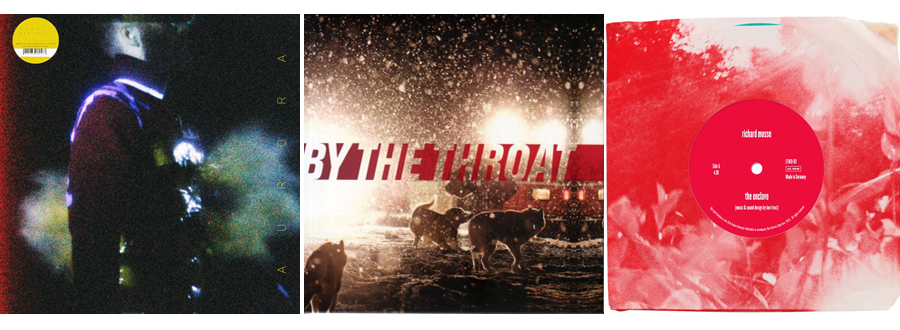

Richard Mosse: Ben, I’m about to embark on trying to find or embrace the unknown again. I’m trying to dismantle my work, my big, long four-year project in Congo. And I find that taking that leap into the unknown is one of the emotionally hardest things to do, but it’s fucking cool when you get it right, when you really take a leap from the fiery building into the darkness. It’s hard to do correctly, to really challenge yourself to work against your instincts, your reflexes, and to rip up what’s come before. But I’m thinking that your most recent album A U R O R A came out of that same challenging space somehow. You’ve had a prolific year, creatively. Aside from your album, you’ve produced an opera, The Wasp Factory, you’ve gone to Congo twice and made a piece for the Venice Biennale with me. It’s all coming from a very loud place. Can I ask you why you titled the album A U R O R A?

Ben Frost: Well, as you’re well aware, that was not the original title. When you work in this realm of digital music, from day one you’re sitting on the airplane and you’re making some basis for a song or a piece of music. And then the battery’s got three percent left in it, and you’re like, “Fuck, I need to save it! Yeah, ‘Emergency Zero Five!’” And then that piece of music is called “Emergency Zero Five” for the rest of its life, right up until that point where you actually have to give meaningful titles to things. And you have to consider, “Is that the title? Or am I going to completely change the meaning of it to direct the ear in a different way?”

With A U R O R A, the original title was Bulletproofing. This was far more connected to The Enclave; it stemmed from the bulletproofing ceremony in the film that takes place where you see this prophet do this water blessing over his soldiers. They then literally believe they’re bulletproof. And what I took from that was this idea of armament, of shielding oneself from harm. Which fit into my practice, into my life at that particular time in a major way. But then as time went on, that title became less and less relevant because I felt like the term “bulletproofing” had this negative twist to it. It’s a protective measure; it’s a defensive stance rather than offensive.

Whereas with the idea of the aurora, I read this German alchemist called Jakob Böhme who did this big dissertation on the aurora as a concept of the dawn and as the pinnacle of the alchemic process, where it’s about the expulsion of darkness. This idea that the dawn is not so much about light coming in, it’s about light pushing the dark away. To me, it spoke of an offensive move, as opposed to protecting oneself. It became about pushing back. The more I thought about it, the more I felt like that’s what that record is about: using light as an offensive gesture.

RM: That’s one possible interpretation of my Congolese works, the way the surveillance film technology turns the green foliage pink. We were sitting in a bar and you were saying, “The use of the infrared film in Congo almost evokes the potential for hope, for growth, for rebirth.”

BF: I’ve been really adamant about making that known to people. I feel like that’s a small misstep in the communication about Infra and about The Enclave—the way in which the technology is misunderstood. This idea of infrared, I think people understand it as this heat-seeking technology or something. In the context of that film, it’s not about heat, it’s about the permutation of life.

RM: It picks up on the health of the plant, potentially for Congolese wealth. There are four rainy seasons a year in eastern Congo, and the soil is really rich on account of the recent volcanic activity in the region. The landscape is incredibly fertile, yet many people are starving. It’s a rich country in spite of its poverty.

BF: The Kodak Aerochrome film will react differently to a living plant. If you paint something green, if it’s made of metal, the film reveals that in a completely different color to the surrounding vegetation, even though it’s the same shade of green in the visible spectrum. But if it’s a living plant, it glows pink. But if it’s a dead plant, it will just stay dead, it will stay brown.

RM: So, it’s like in Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain. Was there anything in your personal life that was shit that you tried to turn to gold, to sublimate?

BF: I think with the perils of one’s personal life, you can either allow yourself to be a victim of those or you can push past them and make an offensive stance. Also, that’s an idea that for me is totally connected to my experience of being in DRC, just the complete banality of my stupid, white peoples’ problems. This kind of glaring awareness of how insanely coddled and stupid all of the things I worry about and spend time sweating emotionally about are in the face of what is an actual problem in a place like that; arguing with my ex-girlfriend on Skype while people are shooting at each other down the road…I often wonder about how you reconcile that? You’ve had to deal with that not only in the Congo but in Iraq, Gaza. But it’s not something that you just isolated to the outskirts of Goma.

RM: I think that my own works try to be true to the beauty of Congo, eastern Congo, particularly. And not to hide that away and say, “Oh, actually, it’s all just a hopeless disaster. Woe unto them. Pitiful squalor.” That’s a complicated gesture. It’s hard to own a really complicated and also problematic gesture when it comes to human suffering. There’s an ethical code there, which I’m attempting to break.

BF: Why?

RM: Because I think it’s dishonest, in a way.

BF: I agree with you, but I’m curious as to why.

RM: I think it’s out of date. I think it needs refreshing. There’s no red blood cells left when it comes to representing the Congo. I think where there’s tension, it’s always a good thing. When people are offended, there’s something genuinely at stake. And I’m not talking about shock factor here.

BF: I say that’s the interview answer. And I mean that in a way that it’s your answer now that you’ve had time to think about it, but I can’t believe that’s what you were thinking about when you started. I got pulled up on this a bunch of times in interviews, where people are asking me to define all the aspects of A U R O R A. And I’m like, “It’s just come out. Ask me in two years what it means to me.” And I feel like you’ve had more time now with The Enclave.

RM: Too much time.

BF: But my point is, when you think about when you first went down there, that genuine curiosity about the situation down there, surely you didn’t go with this idea that you’re going to turn photojournalism on its head and reveal something new about the conflict in Central Africa and blah blah blah.

RM: No, definitely not.

BF: So then why?

RM: It evolved into a public gesture, of course, but it started in a very private, intuitive place—a place of blindness, linguistic failure and transgression. I wanted to transgress not just photojournalism, but also myself. And over the years the project found momentum, and developed into a kind of advocacy. An advocacy of seeing. A problematic advocacy nonetheless, deliberately so, and still wracked with transgression. But you’re right, the conversation currently surrounding the work is far from the project’s beginnings. Ideas evolve over time. It’s a journey.

BF: If I’m completely honest about it, and I want to be, there were a lot of really fundamentally childish beginnings in A U R O R A—some really garish, undistinguished, stupid ideas. I wanted to see what it would be like to make dance music. Or what happens if I just work with drums? And my contention is that probably you had a similarly really base level set of ideas that you wanted to get at…

RM: Oh, definitely.

BF: …that have since become much more complicated and you found a way to talk about it and justify it and expound upon it. And also, in reflection, you realize what it is that you were actually interested in. But that thing only ever comes later.

RM: In the beginning, I was just sick of what I was already doing. I felt I had exhausted the possibilities of my methodology and needed to throw away the crutches.

BF: You could have become a very successful photojournalist, if you had just done what you were told.

RM: In some respects, my work in Congo has been a parody of photojournalism, an attempt to question that belief system. But I was also sick of myself, of my monumental approach. My images were so hyper-focal, big, and masculine. I wanted to subvert myself, ultimately. That’s one of the reasons why I chose to use this pink, kitschy aesthetic, because I realized that war photography is an essentially macho thing. I wanted to do it in such a way that’s feminized. It was really an assault on my own comfort zone. And through that, you start to bring yourself into the unknown.

It’s not just about yourself though. And if it’s successful, it will allow you to start to think about other things, as well. It’s all about your response, your intuitions. And that’s exactly what you were doing with A U R O R A, right? Because you changed the rules. And this is something I’m thinking about a lot, all the time. After Venice, you told me I should change all the rules. That’s hard to do unless you’re really ready, like you’ve got to hit the bottom. It’s really hard to throw away your methodology, particularly when it’s been successful. Like with the album you did a few years ago, By the Throat. It’s a beautiful piece of music, but you threw away strings, right? What else did you throw away?

BF: Guitar, piano, a new studio…

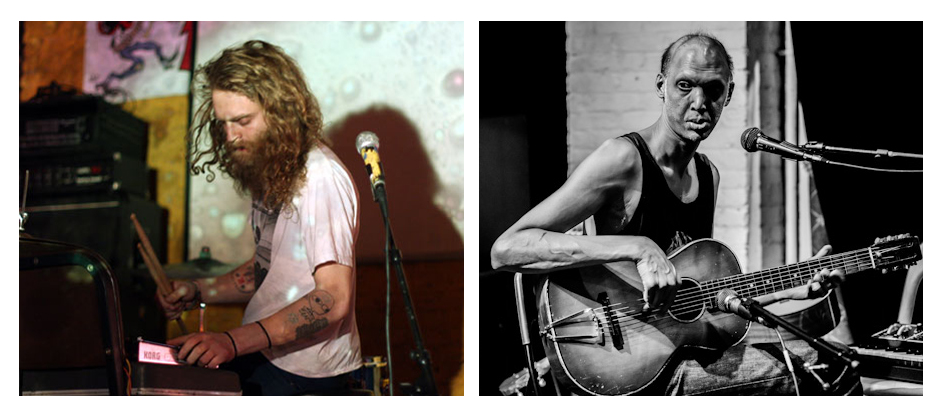

RM: Visually, on stage, I’m sure you’re aware of this, but—as far as I know, no one talks about it—Greg Fox, who used to play in Liturgy and now is performing with you, looks like this hippie, with free-flowing, long hair; his posture radiates open positivity. Too much yoga, veganism. He’s on the left, and on the right is Shahzad Ismaily, who’s sort of a Satanic creature with a hoodie. It’s total dualism, Manichaeism. Now, was that scripted? Did you meet both of them and think, “Oh fuck, this will look great on stage.”

BF: I think it probably began even more banal than that, actually. On one side you have the raised in Manhattan, whiter-than-white metal drummer who just radiates this perfect, Terminator intensity. Then on the other side you have the Pakistani, all kinds of influences coming from every corner of the globe, a manifestation of all that is foreign in Western music, completely off the grid, swaying, polyrhythmic enigma. It was probably something about smashing those opposing forces together, like a particle accelerator. And Shahzad—he’s just a fucking genius, he can play anything. He can play any rhythm. You give Shahzad any aspect of any niche culture music and he can find his way into it within two seconds. Like Greg, he’s one of those people, he makes me feel stupid every time I’m in a room with him, on a creative level.

RM: That’s good to work with someone who’s smarter than you.

BF: It’s always good to work with people who are smarter than you. I think you do the same thing.

RM: As a rule. Trevor [Tweeten, cinematographer of The Enclave] had a great description. He came up with it immediately and—like all of his ideas—it was a glimpse of the sublime. How did he describe A U R O R A? It was like a freeze-frame of a bullet being shot in an underground rave. It was beautiful.

BF: There comes that point—I guess it’s not dissimilar for you, when you get that first proof or contract sheet back from the lab and you see what you have. Of course you can change the color balance and you can edit the shitty shots out and you can make a collection out of that, you can make a narrative from what’s there, but you can’t fundamentally undo the DNA of it. You either accept it for what it is and work with it, or you just fucking throw it off the table. Because there’s already this intensely powerful current that’s decided where it’s going. And you can divert the stream, you can channel it into a way that powers a certain faction, but you can’t reverse the current. You can’t go back on what it is.

With A U R O R A, it’s the same thing. When I left it alone for six months—which I did—I came back to it hearing it for actually what it is. There was no reverse switch. That’s what it wants to be. And there was that point where I just went, “Is this the record I want to make? Is this my post-By the Throat statement?” And I recognized it exactly for what it is, in that it’s without all of the filigree adornment of By the Throat. The femininity, in a weird way, has been removed. It doesn’t have any of that placating, stroking the back of your head nature that allows a lot of the aspects of By the Throat to exist. I remember, there were a few moments where I tried to nice it up. I played around with it, for sure, to try and dampen it a little bit, but it’s gone. Everything felt like a cheap shot at trying to reconcile something that just refused to be reconciled. It was like trying to teach a rabid dog to sit.

RM: Why did it take you five years to release A U R O R A after By the Throat?

BF: It didn’t take five years. Realistically, it was probably a two-year process of making that record. But before that, fundamentally, I just didn’t really have anything to add. Do you think about that at all—the necessity of your work?

RM: Yeah, I’ve just realized recently that, for the last seven years, I’ve been on this fast track of just hammering bodies of work out on a two-year cycle for the Chelsea gallery scene. And that came out of being at Yale where it’s all the same, except the frequency was more intense. It’s just like you’re running on adrenalin. It’s not healthy. Sometimes you need to take a little time off.

BF: You know, I remember on my first day in the Congo, we crossed the border, we bribed some officials and we got in. We started driving and literally two hours later, I was standing a grave up to my waist, having dirt shoveled on to me and a coffin dropped in beside me. I think that was a “We’re not in Kansas anymore” moment.

Interestingly—and this is something I’ve thought about a number of times—from a technological point, I had one of these field recorders, but I had it hooked up to a pair of noise-cancelling headphones, which completely block noise so you’re only hearing what’s coming through that microphone. In a strange way, it removed me from the situation. And it’s only in retrospect that it feels that it has the gravity that it was lacking at that moment. At the time, I was just like, “I need to get the sound of that dirt.” It’s an instinctual gesture, but it’s also a didactic gesture. It’s not “honest” in the way I think a lot of people would like to think pure cinema or pure documentaries or pure journalism works. You make those choices along the way. You decide what to show and what not to show, and those choices affect the way the work is perceived.

RM: It’s all about manipulation. It’s a series of decisions. Sort of off topic, but talking about our first trip, you were talking about when you distort digital it sounds nasty, but if you distort, as you do, analog signals, it’s just gorgeous. I’ve been thinking about that idea a lot, because I’m basically distorting an analog signal by using grainy, old military film technology that’s silver halide film—if you did the same with digital, it would look like vomit.

BF: But don’t you think there’s a historical nostalgia for that as well? I feel like people are going to look back on the late nineties, they’re going to listen to all of these dogshit recordings where people were just coming to grips with digital recording techniques. And with digital photography, like the first Kodak 72 dpi photos. They’re going to look at those and they’re going to aestheticize them in a way that’s like, “Oh my god, it’s so digital! I love it!” And there’ll be an app on your iPhone that “makes it look like it’s a pixellated piece of shit,” because that’s what will be in fashion at some point. It will be the acid washed jeans of photography. How do you feel about the fact that your work will be at some point distilled into a plugin in Photoshop? The Infra? Like a Richard Mosse plugin?

RM: I think it already has. About two years ago, they made an infrared app for the iPhone, I believe. Unfortunately, they didn’t put my name on it, I didn’t make my millions. I don’t own the medium. The harder one to swallow was the first five minutes of Star Trek: Into Darkness. You sent me that first. I didn’t believe it, but then I was on a plane and I watched it and was appalled. It’s not just that they turned the trees red and pink. The people on that planet are dressed like African tribesmen. But not only that, do you remember the planet was being destroyed by a volcano? In the first five or ten pages of my Infra book, it’s basically step by step honing in on Mount Nyirangongo, an active volcano with an enormous lava lake boiling away, which last erupted in 2004, destroying the city of Goma.

So you have specific characters here: African-styled tribesmen, a red jungle, and a volcano. Many people came to me, separately, and told me that they reckoned the people who made the new Star Trek film had obviously seen the Infra book and were like, “Hey this is cool! Why don’t we just copy this and call it this weird planet in Star Trek?”

And someone made a music video for A$AP Rocky’s “Wassup” in which the band members are made to look like gangsters in an infrared environment. They tweaked the color of the grass and bushes digitally so it’s pink.

BF: I can show you so many more examples of people ripping you off, you don’t even know. But I have a different question. So, you’re seeing someone and they start sleeping with somebody else. Does that entice you further into their world, or does it repel you?

RM: Repels me.

BF: Yeah, exactly. I think there’s two kinds of people: the ones that would go harder into that or just back off completely. As soon as it becomes the thing that you lose a stake in, as soon as it’s not yourse anymore, it dissipates the energy that surrounds it and requires a certain level of willingness towards self-destruction to just tear that down and move away from it. After By the Throat, it was open season. It became every man and his wolves—so many leachers. And that doesn’t make me want to make By the Throat Part 2. It just makes me want to get as far the fuck away as possible. They can just have it.

RM: Yeah. But if I had said that in 2011 after Infra—by rights any sane photographer would have done: “OK, I made the book, I did the show. On to the next thing.” Then I wouldn’t have made The Enclave, which is a total evolution.

BF: Do you think it’s important to be the first with an idea?

RM: I do, actually.

BF: Me, too. I think originality is the only thing, it’s the last rung on the ladder.

RM: The top rung or the bottom?

BF: The bottom. Everything else is just aesthetics and social climbing. The bottom rung is having something that you’ve come up with on your own.

RM: That’s weird, it’s the bottom rung. I would have thought it was the top rung. What’s the top rung?

BF: I don’t know, having some celebrity girlfriend who can elevate you to the upper echelons of importance or whatever. Having a sex tape. That’s the top rung.

RM: Well, that’s my next project.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. The Winter 2014/2015 issue hits shelves this week.

Published December 16, 2014. Words by EB Team.