‘Black Album / White Cube’: Visual Artists Explore Collective Resistance in Music

Kunsthal Rotterdam's newest exhibition features works by Arthur Jafa, Exactitudes, and Sven Marquardt, among others.

Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums, 2013-2019. Foto installatie: ‘Black Album / White Cube’ bij Kunsthal Rotterdam, Bas Czerwinski

At Kunsthal Rotterdam, there’s no fear of a “Heute leider nicht” from the notorious Sven Marquardt and his formidable posse of Berghain gate-keepers. For the museum’s first post-lockdown exhibition, entitled Black Album / White Cube, the roles have switched. Now it’s the observers that assume the discerning gaze. Marquardt’s large-scale, black-and-white portraits of his colleagues assume the more vulnerable position amidst their blunt dispositions.

Traces of muffled bass and syncopated, EKG-like piques from Robert Hood’s minimal techno track “Minus”—accompanying Arthur Jafa’s video piece “APEX”—ominously circuit throughout the space. And a miniature replica of Berghain by Philip Topolovac, ironically titled “I’ve Never Been to Berghain,” grants viewers permission to enter the white cube that houses Black Album / White Cube.

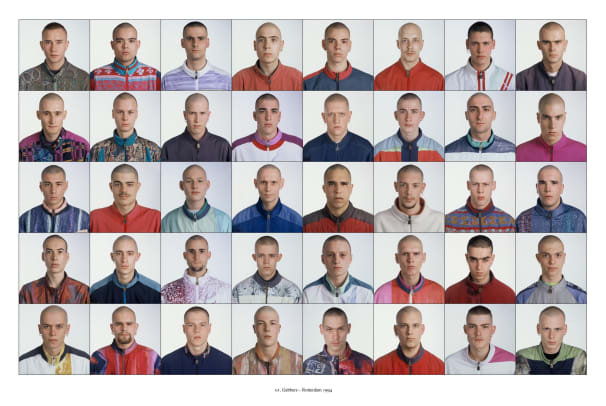

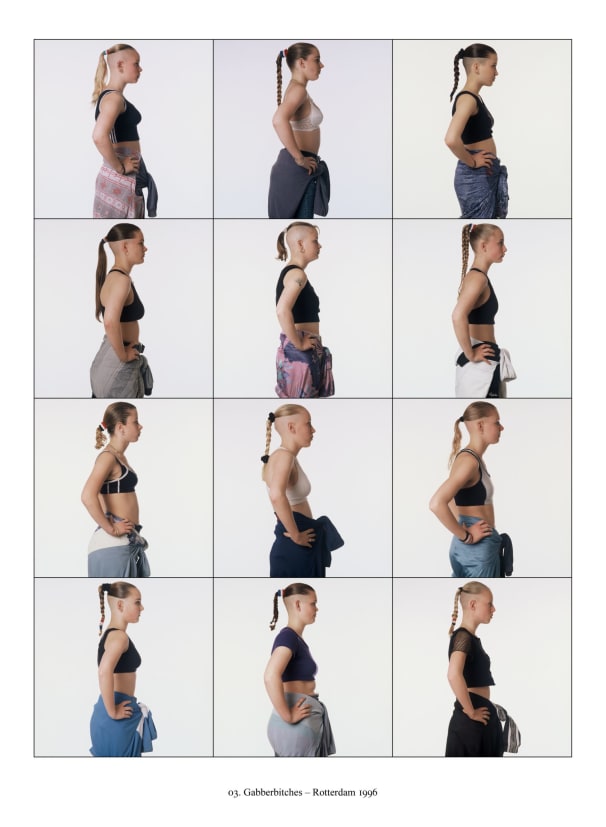

Curated by former Telekom Electronic Beats editor-in-chief Max Dax and Kunsthal Rotterdam’s Eva van Diggelen, Black Album / White Cube exists at the intersection of art and music. The exhibition, originally titled Hyper!, was initially shown in 2019 at Deichtorhallen Hamburg with over 60 international artists. At Kunsthal, it has taken on a different title and a truncated list of artists while including Dutch heavyweights like photographer Anton Corbijn and the illustrious duo Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek, who curate cult street fashion study Exactitudes.

The four-chaptered exhibition functions as a mind map, both visibly and invisibly connecting the dots of our post-postmodern, digital era to reveal the prevalent processes of cut to copy, sampling to resampling, appropriation to post-representation, and immaterial to material. It shows how, though fundamentally heterogenous elements, art and music turn to each other for survival.

While history has always delineated the patterns of collective effervescence and joy necessary in binding marginalized communities, Black Album / White Cube delves beyond the transcendental, Dionysian sensibilities of music; it highlights collective uproar and pain as inescapable qualities omnipresent in the interwoven flux of music, art, and politics.

Take, for example, the emergence of the Rotterdam gabber scene. Rotterdam was a wounded port-city traumatized by war and rampant economic strife. Young people weren’t able to voice their frustrations of the post-war trauma their parents experienced—and subsequently turned to distorted, chemically-induced, 200+ BPM sounds as refuge and hedonistic revelry. Ari Versluis, who documented the Dutch gabber scene in typological photography series Exactitudes with Ellie Uyttenbroek, recounts the Rotterdam gabber scene in the early 1990’s: “Whether it’s hip-hop or gabber, it really comes from the streets. There was a huge explosion of do-it-yourself culture, making record labels, making record stores, making logos, making their own style. When it comes from this part of society, it has to do with getting a grip of pain or a communal sense of destiny.”

It’s precisely the visceral immateriality of music that escapes the scope and authority of predicative language and semiotics. Berlin-based painter Bettina Scholz translates this immateriality in her dystopic triptych, individually titled “Blade Runner 2049,” “Qualm,” and “Solaris.” Taking inspiration from Benjamin Wallfisch and Hans Zimmer’s Blade Runner 2049 film score and Helena Hauff’s gritty, acid-soaked album Qualm, Scholz’s synesthetic process forms subliminally, resulting in raucous and even gothic abstractions in her acrylic glass paintings. Referencing this synesthesia, Scholz comments, “When I hear music, I see colors in my mind.”

Beyond the immaterial lies music’s crossover from being a mass-produced entity to an individualized set of lived experiences. Artist Rutherford Chang began collecting The Beatles’ epochal White Album in 2007 and has now amassed 2,643 copies on vinyl, which are displayed in his installation “We Buy White Albums.” Through demarcations of intimate, handwritten notes, sketches, coffee stains, and water damage, each copy adopts its own unique narrative. These relics of the album—and of music as an oscillating form—speak to its influence in our collective memory.

The exhibition all comes together with Arthur Jafa’s video piece “APEX,” where he spotlights the aggressive dialogue between art and music. The epileptic video quickly cuts to each downbeat of Robert Hood’s “Minus,” revealing the grueling but necessary connections of Black history in relation to pop culture. A rapid-fire flutter of 841 archival images of lynchings, cartoon characters, celebrities, people in Black face, and outer space beckons the voice inside to “not look away, not now, not ever.” “APEX” is too often hastily described as an examination of the Black gaze, while giving voice to the indisputable role of Black consciousness and ingenuity in American pop culture. While not entirely false, this hasty assumption fails to recognize two points: one being the embedded, universal presence of the Black gaze in our collective psyche and the second being the connotation of a specifically American issue, which does not recognize the proximity of African diasporas internationally. Jafa’s “APEX” is all-encompassing; it acts as the epicenter of entangled powers illustrated in Black Album / White Cube.

The perennial themes of dancing, revelry, and jubilation can not be detached from collective despair and resistance. The history of music, whether it’s jazz, Baroque music, rock and roll, or techno, is intertwined with a fearlessness that renders festive moments subversive. A subculture, an audio piece, or an artwork never stands alone in this world. And if we’re not careful to place these radical departures in perspective, these precious snippets of time will pass us by without a second glance.

Jocelyn Yan is an artist and writer based in The Hague. Follow them on Instagram @midnightbisou

Published July 01, 2020. Words by Jocelyn Yan.