Clouds’ New LP Is The Best Post-Apocalyptic Techno Concept Album We’ve Heard All Year

Clouds and graphic designer David Rudnick talk about the Scottish techno duo's brutal new 'Heavy The Eclipse' album and its immersive Neurealm website.

The records stop four hundred years in the future, after the lines shut, and the corporation withdrew. What we know of how we got here is pieced together by the fragments of the rail maps and the corporate orders that survive. After numerous waves of social collapse, Glasgow, a once prosperous city, had run to waste in lawless ruin.

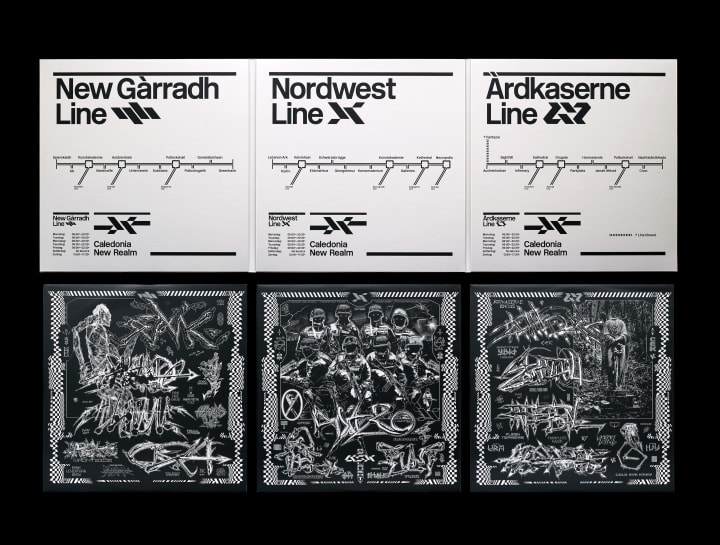

These words, digitally etched in 2-bit script—along with a set of poorly-rendered, indiscernible logos emerging from a flat, black void—are the first things that greet you when you visit Neurealm.net. As the automatic scroll plunges you deeper into the site, whispering metallic sounds filtered through an abyss of reverb give the sensation of exploring some ancestral cave, its paintings a flickering, unfolding web of graphics, primitive writings and grotesque graffiti. This is Neurealm, an immersive world built by graphic designer David Rudnick and techno duo Clouds for their massive new album Heavy The Eclipse, which is out now on Speedy J’s Electric Deluxe imprint.

The deeper you go into the music, visuals and the story of this place, the more its unique take on science fiction pulls you in, and the harder it is to leave. Through its expansive use of sound design, powerful visual aesthetics and web-based experiences, Heavy The Eclipse and Neurealm effectively break down the tropes of hardcore, techno and science fiction to create yet another possible future for electronic dance music that’s different from but also reminiscent of similar currents emanating from the crossroads of these aggressive genres.

Heavy The Eclipse is, on a sonic scale, nothing short of monstrous. And yet it won’t satisfy those looking for a compilation of strategically-structured, disposable dance floor “bombs” or “bangers”. It is a conceptual work that plays out more like a film where scenes comprised of atonal noise matter just as much as its dance floor cuts. “These tracks cover so much ground musically,” says Rudnick of Clouds’ production work. “There’s no point where they decided, ‘Ok, this one’s a big room banger’, or, ‘At this point, we’re going to put the narrative to the side and just go for an ambient piece.’ The whole thing is coherent and so detailed.”

That’s not to say that Heavy The Eclipse‘s beats aren’t huge; they’re just not what you’d expect. The album’s second track, “Clubber’s Guide To Wreaking Havoc”, is a proper techno bomb, with enough thundering, sub-heavy kicks and overdriven hi-hats to satisfy any veteran head’s cravings, but the way Clouds fill the rest of the frequency spectrum is infinitely more interesting. Hardcore hoover synths, slippery lead lines, chain samples and vocals that sound like they’re delivered through a thick coating of slime are all haphazardly spread across the track’s beats, giving it an aesthetic best described as “corroded”.

My gripe with contemporary science fiction is how thoughtless and pastiche everything feels—how everything is like a moodboard leaning on Blade Runner or a narrow docket of influences

When they speak about the album, the common words Clouds and Rudnick use to describe the world they’ve built can come off like insults. But in this context, describing something as “horrible” or “gross” means that they’ve adequately communicated the way the surroundings feel. For example, they developed a series of graffiti tags for the various gangs, or “Krews”, that govern the fictional city’s abandoned rail network. Describing the style, Rudnick says, “It was more important that we reflected the character of the gangs than it was to make some sick graffiti. The end style we came up with is repulsive. It looks like vomit and spleen. It’s grotesque, but I’m really quite proud of that. It’s a different kind of raw to what people are expecting.”

In Neurealm, nothing is pretty. Heavy The Eclipse’s scale—in terms of its sense of decay and the feeling that things are falling apart—led the group to completely abandon the use of the sharp, clean graphics they had been known to use in the past. Rudnick claims the album’s sense of grain, corrosion and noise made it impossible to use a single clean vector edge in the project’s visual design.

Instead, building from the ground up, they developed its style through a series of unorthodox experiments. The graffiti was created accidentally: drawing with overly-inky markers led them to start dabbing and smearing their tags with napkins. The result was the oozing and splintered lettering they thought the gangs deserved. For Neurealm.net, Rudnick made the masochistic decision to create the site’s text and graphics with a primitive 2-bit drawing system. He painstakingly colored in its chaotic visuals pixel by pixel. This over-the-top detail shows. Neurealm looks nothing like Rudnick’s prior work, and it helps to create a world that feels expansive and virtually inhabitable.

This is due in large part to the project’s backstory. Set in a futuristic Glasgow, Neurealm is a disintegrating world governed by drugs, gangs and violence—one where factions control abandoned rail lines and inhabitants throw endless raves. The website’s long side histories about societal collapse, failed urban development and the rise of the city’s Krews feel similar to the dense lores that structure science fiction series and role playing games—yet the brand of dystopian darkness and collapse feels strangely unlike any of these genres’ famous titles. Everything about Neurealm’s history, all the way down its setting in Glasgow, was designed to avoid stale, rehashed science fiction tropes.

“My gripe with contemporary science fiction is how thoughtless and pastiche everything feels—how everything is like a moodboard leaning on Blade Runner or a narrow docket of influences,” says Rudnick. “It goes against the entire essence of what I think makes sci fi interesting.” This unique narrative came about naturally after the record was finished. Rudnick remembers that it was only after several listening sessions that the duo were able to form the core ideas behind Neurealm from the subconscious ideas they heard in the music.

Both Clouds and Rudnick seem repulsed by the idea of writing a techno album as a “fake cinematic soundtrack” or changing the music to accommodate some lofty ideological goal. Clouds’ Calum Macleod says, “I don’t want it to come across like we’re just injecting some kind of concept. It’s there. And we’re still exploring the meaning ourselves.”

One hope they all seem to have, though, is the recontextualization of this music. They claim they want to “open up a different environment for people to view techno or hardcore music in,” saying, “The concept for this album is not to be big room music for some massive Dutch warehouse. That is definitely not what it feels like, why it was made, or how we want to convey it.”

The trio’s ambitions for the music go far beyond the scene altogether. They hope Neurealm will open up dance music’s air of exclusivity, claiming they’re equally if not more excited to hear what “total normies” think about the experience as what seasoned hardcore veterans do. In any case, with a release this innovative, it’s inevitable that Heavy The Eclipse and its Neurealm concept will expand far beyond techno’s narrow confines.

Clouds’ Heavy The Eclipse is available now. It can be purchased on Bandcamp or streamed on Spotify. To download your brain into Neurealm’s virtual world, click here.

Published December 05, 2018. Words by Zach Tippitt.