Eastern Haze: December 2013

In her monthly report, Lucia Udvardyova tracks the movements in and from the best of the Central and Eastern European sonic underground, distilling the best of her Easterndaze blog.

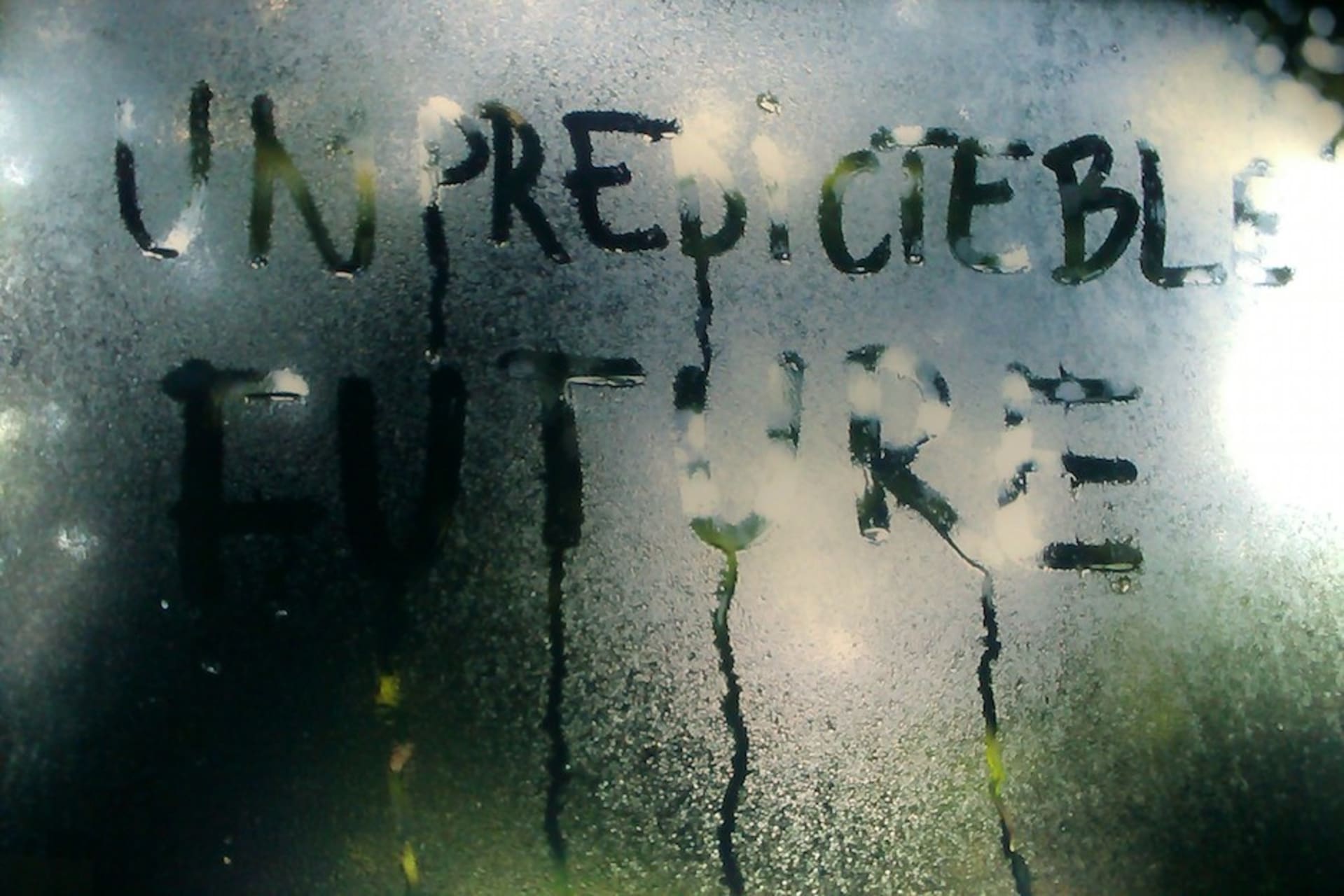

Main image: “Untitled (unpredicteble future)” (2004) by Mircea Cantor—photo taken by Lucia Udvardyova at the MNAC, Bucharest.

It’s Saturday night. I’m tagging along with a bunch of Moldavians through the periphery of downtown Bucharest passing chaotic traffic, horns, flamboyant Las Vegas-style Christmas street decorations, eclectic architecture that defies any categorization and well-dressed passers-by—an amalgam that is one of the last havens of self-contained anarchy in Europe. As I rush via Piata Universităţii, the square loaded with meaning where most of the protests and demonstrations usually take place, including the 1989 one, I talk to protesters who gather in the freezing cold to voice their support of farmers fighting a corporation in a bid to save their environment. I’m a bit hungover from last night; I went to see the post-punk stalwarts Soft Moon supported by local EBM-inflected act with a rather suggestive German name, Tanz Ohne Musik. I’m still not sure whether I liked either of the gigs.

During the week, I visited the flat/studio of the guys from Future Nuggets located in the old town which, strangely, looks like Potemkin village. Future Nuggets is a collective, label, cross-pollinary music project and a group of sonic enthusiasts who, a couple of years ago, rediscovered the Romanian psych electronic rock project Rodion. Coincidentally, I also get to meet them too as they’d just returned from Moscow. Rodion Ladislau Rosca is an affable man in his sixties, with whom I speak Hungarian. We sit on the couch, they talk animatedly, and in spite of the several generations that divide them, there is a mutual respect and camaraderie that binds them. He tells me about the love for his mother and the trauma that her death—just few months ahead of the execution of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu—caused. He, in effect, became disinterested in music for more than two decades, leading a modest life in a Transylvanian village. There is a new documentary about Rodion, which is due out next year.

Future Nuggets’ members, apart from playing in Rodion’s newly reformed band, have a band called Steaua De Mare, a hypnagogic instrumental project that delves deeper into the recesses of Romanian collective and personal history, “flirting with progessive-manele and other international and outernational crossbreeds.” They also have various side projects, for instance the amazing Plevna. The collective stands out as it doesn’t shy away from recontextualising their own musical heritage—such as manele—and placing it within a modern context. One of the members of the group, Andrei Dinescu, who looks like a young Todd Rundgren and whose father is a famous Romanian poet, has played with a prison band, for instance.

Manele is a Romanian music style largely performed by highly skilled musicians, lăutari, from the local Roma community, which in the past would have been denigrated for its “lowbrow-ness”. Gradually, the downtown youth has fallen in love with the music their parents loved to hate, dancing to it in dingy basements and listening to it on YouTube while the music itself has mutated and embraced electronics. Manele was previously unofficially prohibited from the public realm, banned from the radio and basically relegated to weddings and restaurants where you have to book a table in order to hear it. I talk to Adrian Schiop, a writer who has just published a fly-on-the-wall autobiographical novel about a love affair between an ex-con and a scholar set in one of Bucharest’s most deprived areas, the Ferentari. He also did a PhD on manele and happened to YouTube-DJ at the aforementioned basement, with the indisputable king of the genre, the amazing Florin Salam, on heavy rotation. Schiop considers manele one of the most authentic musical movements to emerge in Romania, being much more authentic than, say Romanian hip-hop, which can be perceived as one of the symbols of the “self-colonisation” of Romanians, avidly adopting Western models of modus operandi without critical reflection.

I also get to hang out with my friend Gili Mocanu of Somnoroase Pasarele, a painter and a musician who has a studio in the Lizeanu district. An epitome of post-communist dystopia, Lizeanu is an area where the old and the new worlds come together and collide. Uniform concrete block estates where hustlers, junkies and enterpreneurs of various kinds abound. As Gili plays me his haunting rework of Ceausescu’s last speech, the electricity in the whole block eerily goes off, and on again, and off.

The Romanian capital remains elusive and somehow subliminally claustrophobic, like the music of Iancu Dumitrescu, a doyen of Romanian avantgarde composition, whom I don’t get to meet. In a way, Dumitrescu’s legacy looms large, mostly abroad, but Gili’s music, in some liminal way, is a continuation of this aesthetics.

Rochite’s music, then, embodies Bucharest. It’s inane, playful and utterly lovable.

I spend most of my days roaming the streets, hanging out with strangers and recording in order to capture the moment, the transition, the fissures and seams, and hoping that they won’t evaporate in a bid to instill “normalcy”. ~

As part of a programme courtesy of the Romanian Cultural Institute, Bucharest. You can read previous editions of Eastern Haze here.

Published December 17, 2013. Words by Lucia Udvardyova.