Calabrian Tarantella: Trance, Drone and the Rituals of the Mafia

“If it were not part of Italy, Calabria would be a failed state. The ’Ndrangheta organized crime syndicate controls vast portions of its territory and economy, and accounts for at least three percent of Italy’s GDP (probably much more) through drug trafficking, extortion and usury. Law enforcement is severely hampered by a lack of both sources and resources.”

– Cable from J. Patrick Truhn, Consul General, exposed by Wikileaks

“And when I was born / I was born crying / And the midwife ran away and screamed / A child of bad luck has been born.”

– Giuseppe Colosimo, “Quannu niscivi iu” (“When I was born”)

Songs of Beauty and Evil

Speeding along the autostrada through the craggy Mediterranean landscape at the southern tip of Calabria, two things dominate the coastline: the volcano Mt. Etna, which has been emitting black smoke for the past two weeks, and the myriad construction ruins that dot the region’s steep hillside. The buildings are in various states of completion and range from medium-sized houses to fully blown architectural absurdities made of ludicrous amounts of concrete to form shapes that appear to have no function (obvious even to the untrained eye). Referred to simply as “disgraces,” they serve as a constant reminder of the political corruption and organized crime endemic to Calabria. I am sitting shotgun and holding on to the edge of my seat with Hamburg-based journalist and photographer Francesco Sbano at the wheel. A native of Paola, a small town some two hours north of the region’s most populated city Reggio di Calabria, the tall, silver-haired Sbano is a controversial figure in Italian cultural circles. Over the past fourteen years, he has become the go-to guy for countless international media interested in getting face time with members of the Calabrian ’Ndrangheta, currently Italy’s most powerful mafia organization. But he is even better known for promoting and distributing the lone cultural contribution of the ’Ndrangheta to Italian culture: its music.

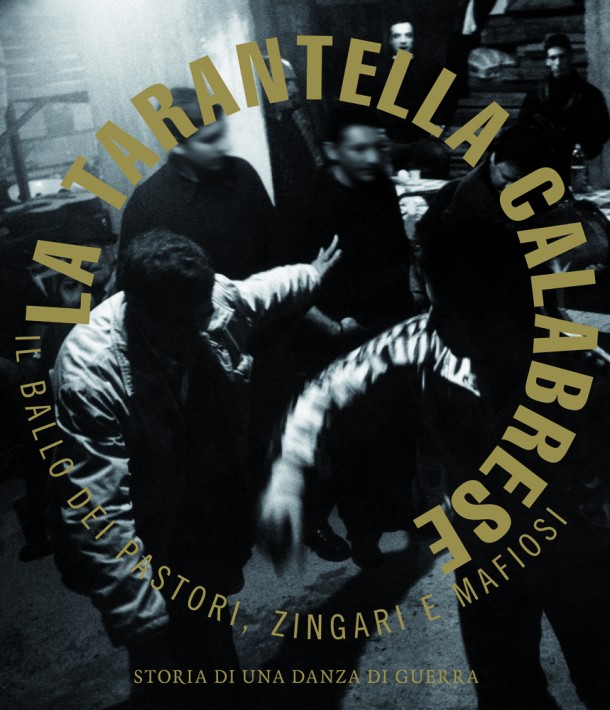

Since 2000 Sbano has released several volumes of so-called malavita songs, a genre of mostly acoustic Calabrian folk that romanticizes the trials and tribulations of ’Ndrangheta members’ lives of crime. Lyrically, the texts are often written by or based on stories of imprisoned Mafiosi and usually take the form of a wistful lamentation, with the narrators singing their hearts out about not receiving enough visits or being forced to kill out of honor or about never talking to the police—all to the pace of a slow waltz. Sbano, with the help of some of the genre’s most beloved songwriters, mined hundreds of malavita cassettes for the compilations, which together have since sold more than 250,000 copies worldwide. Almost overnight, music that had been exclusively available in small town markets or specialty record stores in Calabria was being distributed and discussed all over the globe, and just as quickly condemned by various European anti-mafia organizations. Critics accuse Sbano of spreading mafia propaganda and creating folklore out of brutal gang activity. Having become something of a thorn in his side, they regularly protest his work and public appearances, which currently includes the release of his fourth and perhaps most compelling compilation, La Tarantella Calabrese, documenting the relationship of the Calabrian tarantella to the rituals of the ’Ndrangheta.

As Sbano explains over long lunches and many hours of driving, Calabrian tarantella, known locally as sonu a ballu (music for dancing), presents a kind of historical blueprint of malavita culture. Unlike classical tarantella from Apulia, which gained its name in the Middle Ages as a kind of musical exorcism for the effects of spider bites (tarantella is Italian for tarantula), the classical Calabrian tarantella is said to derive from the ancient Greek Pyrrhic dance, a dance of war. ’Ndrangheta tarantella ceremonies don’t just celebrate the criminal class in song—they also play an integral role in their rituals. Unlike the dozens if not hundreds of different kinds of regional tarantella in southern Italy, an ’Ndrangheta tarantella is a codified ceremony reinforcing or establishing new clan hierarchies and held on special occasions, from successful acquisitions to the release of a clan member from prison. It’s almost always the local don, or someone delegated by the local don, who decides which two dancers will dance together within a circle of potential participants, with the first five men chosen representing the elite garde of the clan. While most dances are purely celebratory, occasionally they can become a dangerous competition when the goal becomes to literally dance circles around your partner as a form of athletic dominance. Responding to a challenge with a knife or a stick is an uncommon but not unheard of way of defending your honor.

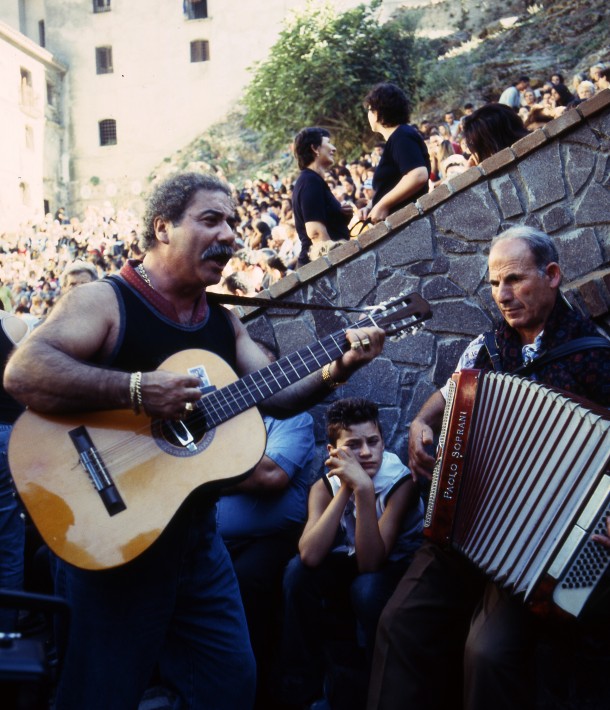

Musically, the Calabrian tarantella is an endless melodic cyclone, frenetic and extremely hypnotic, as I experienced personally during a ceremony with Sbano and numerous ’Ndranghetisti in a clubhouse in a valley of the Aspromonte mountains. Following a memorable meal of pasta with pig lard and massive piles of grilled meats, one or more tambourine players began to set a pace in 6/8, while small box accordions move back and forth between two chords and simultaneously weave a dizzying melodic tapestry. Floating atop the sonic melee were guitars, lutes, lyres, shepherd’s flutes, and the music’s most trance-inducing element, a traditional Italian bagpipe made entirely of wood and goatskin. The instrument’s reedy drone was actually more of a constant wail and synched stunningly with the occasional singer, who belted out stories of love, farming and honor in powerful bursts, with the ends of his phrasing held and wavering until they find their harmonic home, mostly unisono with the drone. The power and elegant inaccuracy of the singing in Calabrian tarantella—particularly that of Antonio Serra or the late Fred Scotti, both of whom feature prominently on Sbano’s most recent compilation—reminded me, in my thoroughly non-ethnomusicologist referential nexus, of the vocal stylings of Jeffrey Lee Pierce or Kevin Coyne. Indeed, the music’s most entrancing strains have retained the historical traces of a kind of musical exorcism.

For Francesco Sbano, promoting music so intimately related to the ’Ndrangheta has become tricky business, but not because he struggles with the ethics. In the five days we spent together he often and candidly expressed a deep mistrust of Italian politics and the country’s judicial system. What at times appeared to border on cynicism revealed itself as the crux of a struggle I associate with the work of artists like Josef Beuys or Viennese Actionists: that is, artists that encourage people to accept that, for better or worse, “evil” is sometimes an intrinsic part of things artistically sublime. Or rather: the art is not sublime because it’s evil, but it’s also not to be discounted for the same reason. Indeed, the longer I stayed in Calabria, the more paradoxical the situations appeared and the less the appearances revealed the true nature of the things themselves. More than one Mafiosi’s crumbling apartment building from the outside revealed itself to be a spotless luxury abode from the inside; the smallest, most harmless-looking guy in the room turned out to be the ruthless bodyguard with the longest criminal record; a young but senior ’Ndranghetista responsible for cocaine and weapons trafficking insisted we name his hometown while the comparatively small town don would barely exchange a word with us.

“Growing up, I had acquaintances who, at a certain point in their lives, were forced to distance themselves from the ‘normal’ world when they became members of the ’Ndrangheta,” Sbano told me. “I had gone to the beach and played soccer with these people, and suddenly they lived parallel lives. And this is the most surreal aspect of it all, because the parallel world is hard to tell from the normal one. That is, unless you know the codes, and both music and dance are important aspects of that.”

Of course, this also applies to the ’Ndrangheta’s social by-laws, which are firmly established. For Francesco Sbano and myself during the interview process, this meant being identified as non-mafia members who nevertheless pose no obvious threat to the ’Ndrangheta and therefore are to be treated with respect—i.e. having our questions answered either honestly or not at all. In the following series of monologues, our interview partners candidly describe their relationship to the tarantella and, where applicable, their role in a clan hierarchy. With the exception of a legendary malavita songwriter, names have been changed. This is who we met, how we got there and what we ate in the process.

Sergio is a local ‘Ndrangheta boss of multiple villages an hour northeast of Reggio de Calabria. A dark and poorly lit collection of hillside roads led out of the regional capital Reggio di Calabria toward Sergio’s small farmhouse and preferred meeting space. We turned onto almost hidden and unlit paths off the main streets of a local village where nothing was marked. These led deep into the rural mountainside and were oddly better paved than the crumbling streets built by the local municipality. Passing pitch-black fields we pulled up to the base of a small hill on top of which stood Sergio and an acquaintance, their persons obscured entirely by a bright security light which shone directly into our car. I ask Sbano what Sergio’s main form of income is. “People tell me it’s not extortion. They all say, ‘No, he’s a good person. People just give him things.’” I was told to wait while Sbano went up to greet them and explain who I was and what I was there to do. I was certainly not the first journalist they had been introduced to, but wariness remained. After ten minutes, Sbano whistled me out.

At the top of the hill I opened the door and entered a small, brightly lit room that doubled as a kitchen and a clubhouse. I shook hands with Sergio, a short, powerfully built but soft-spoken man with extremely calloused hands that betray his lifelong activities as a farmer. In his early fifties, Sergio has a high-pitched voice and speaks with a slight lisp. His companion, Aniello, is a white-haired older gentleman whom I am told is not a member of the ’Ndrangheta. I take a seat at the table, and Sergio summarily fetches a juice bottle filled with chilled red wine made from his own small vineyard. This is followed by a massive hunk of crumbling, aged, homemade pecorino, which he cuts off in chunks with a large kitchen knife. Then the fennel salami; that morning’s hard, crusty bread, which he softens with cold water; the homemade olives and, finally, the pickled mushrooms. Up in the mountains it was close to freezing and the door to Sergio’s hut was left open for the entirety of our lengthy nosh. About two hours in, Sergio started to feel comfortable enough to talk.

Sergio: The first time I ever led a tarantella was when I was sixteen. I was chosen by the elders of our organization, because—well, it’s hard to say exactly why, but I am pretty sure it was because I was a wild kid: people respected me, I solved problems both with and without my fists, and I had also grown up with the dance. It goes without saying that being the master of the dance is an extremely important role. Depending on the reason for the tarantella and if the rhythm is good, it can go on for four to six hours. I’ve been in trances before, soaked from head to toe with sweat, but only if the specific rhythm is being played from the foothills of my birthplace. I remember that my very first tarantella wasn’t that long, but it was important in terms of figuring out who to choose to dance and why. I recall the first time understanding that it was important to invite dancers from the surrounding towns to dance before my friends. It was a sign of respect and hospitality, one with which you also gain more respect. And I get a lot of respect around here. I am the boss, which means that I am bound to my territory. I don’t go on trips or travel abroad.

Generally, when we host a tarantella only within our clan, then it is full of ’Ndrangheta codes. If a young buck gets smart with an older member, he may raise his hand to tell the youth: “You will know your place, you will respect me—or you will pay the consequences.” Of course, nobody challenges the dance leader because his decision is law, even if this means that they aren’t chosen until later on in the ceremony. This also means that nobody would dare attempt to dance around me.

In tarantella, dancing with sticks or knives is something that happens for tourists, but believe me, it’s not a joke. The tarantella establishes respect and order but it can also be the arena for brutal conflicts. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, people can be carried out on a stretcher. Independently of the danger involved, I always have the best musicians to commemorate the event at hand. I want people to respect our culture. You see, so many things you see around here—the roads, the buildings, the stadiums, the markets—were created by us, the ’Ndrangheta. But only the politicians get the credit. The bourgeois don’t respect what we do. Exporting the tarantella is a way of gaining at least what we contribute to culture. The fact of the matter is that I represent a different, older ’Ndrangheta—one that is fundamentally different than the younger hotheads who operate the trafficking and do all the killing.

Mimmo Siclari is a producer and songwriter of malavita music. Driving west along the beachfront of Reggio di Calabria we end up in a neighborhood on top of a hill not far from the city’s small downtown amidst a series of illegally built tenement-like apartment buildings that run to a dead end. It’s sunny outside but the brightest thing in this dark alley are the whites strung across the clotheslines connecting the buildings. We’re there to pick up Mimmo Siclari, one of the most famous malavita songwriters who records his equally romantic and violent songs right here in his home studio. Siclari in particular has been the object for much criticism by anti-mafia activists and has given dozens of interviews over the years with journalists looking to find out more about the small round man who has been dubbed the 50 Cent of Calabria.

We walk together to a local restaurant and take a seat where Sbano takes care of the orders: a three course meal including an antipasto of pecorino and olives, a primo piatto of pasta and fennel sausage with broccoli and a main dish of grilled meat. Before the interview begins, Siclari immediately asks us to lower our voices regarding Mafia questions as the waitress’s husband is currently in jail. He didn’t elaborate why. When the wine arrives, Siclari begins in a hushed voice to tell us how he first started writing songs for and about the ’Ndrangheta:

Mimmo: The voices in tarantella have a very special quality: they are natural, untrained. These musicians sing beautifully, but it’s not formally studied in any way. It’s an authenticity that’s impossible to teach, I would imagine. The funny thing is that back in the day, everybody loved the tarantella, but only the farmers and the mafia were the ones who openly bought the records. The bourgeoisie would actually send someone to pick up the record for them because it was somehow a crossing of an invisible divide. They were ashamed to buy it, but loved listening to it in private.

Before physical recordings the music and the dance were always one. That’s obviously changed, but for me they remain inextricably linked. Also, it used to be you could always tell who was playing if you heard the musicians from a distance because each had their own distinct style. These days, lots of the musicians attempt to copy what they hear on the record which makes it all somewhat less individual. Certain musical habits have become more widespread and musicians are far more competitive. It’s almost a kind of fight between them, and I’ve seen tambourine players play so fast and intense that their hands are bleeding. And they still won’t quit until somebody picks up another tambourine and smoothly continues on, like with the DJs changing of the guard. The music never stops, it just mutates slightly.

For some musicians, playing for an especially important group of ’Ndrangheta might add extra pressure to perform. After all, it’s an extremely intimate musical relationship that they enter. But this isn’t true for the true musicians. For them it doesn’t matter who’s dancing, who’s listening, who’s armed and who’s not. Of course, there is some overlap between the ’Ndranghetisti and the musicians themselves. Fred Scotti, one of the most famous tarantella singers and musicians, was also in the ’Ndrangheta and was killed in a feud with another member. But there are rules to this stuff and for the most part it doesn’t matter if they’re playing in front of the Madonna, a boss or a group of housewives. The music doesn’t change, only the atmosphere and the intensity when ’Ndrangheta dance. The air is thicker, especially in the Aspromonte, where musically, the tradition is the most pure. And the most intense.

I started out my career by selling cassettes from a wagon, where I would design the covers of the tapes myself. The lyrics were about the malavita, or the criminal underworld, which I had been surrounded by since I was a kid. It’s a different kind of music than tarantella—more like individual songs as opposed to endless rhythms. But they’re closely related. I’ve traveled all over Calabria and I was always fascinated by the respect and behavior of the ’Ndranghetisti, especially speaking in a kind of code. When I eventually spoke to them myself, they were eager to teach me some of the songs and texts because I was so fascinated, which is how I came to compose malavita music myself.

I was really hooked on the power and respect when an ’Ndranghetista solved a little problem I had: I was arrested in a small town on the Ionian coast by the police after it was found out I didn’t have the right license to sell my tapes. Because the local Mafiosi knew me and liked my music, a feared member of the local clan came down to the station to pick me up. When the officers saw him their jaws dropped. They immediately released me and apologized for having confiscated my tapes. They also promised to never confiscate my tapes ever again. From that point on I often had two friendly men stand next to my wagon while I was selling to keep the police away. And they always bought me lunch. At some point a local boss invited me over almost every day for dinner for two weeks. I met his whole family and at some point I became afraid that I would be expected to pay him back for all of his kindness and generosity. But the boss wouldn’t even accept a single cassette. He just appreciated the respect that I had shown them in some of the texts I had written.

Pretty much from that point on I have written almost exclusively about ’Ndrangheta heroes romanticizing this life, while ignoring the more disturbing details of their criminal reality. This was easier to do with the old school ’Ndrangheta, who are different than today’s cowboys who absolutely cannot be romanticized. If you read the newspaper and heard anything about all the cocaine trafficking and all the unnecessary murders, then you know what I mean. But ultimately I write songs about Calabria. This is my land. It’s who I am and it’s what I do. Historically, this part of Italy always got seriously fucked, but ultimately it’s a kind of paradise.

Dario, ‘Ndranghetista and trafficker in the port of Gioia Tauro. Our first meeting with Dario from the port town of Gioia Tauro had been two days prior in the parking lot of a sporting goods store which, according to Sbano, his crew ran and operated out of. I had also heard lots of intimidating things about the wealth and fearsomeness of the ’Ndrangheta’s new garde both by Sbano and by older bosses from smaller villages, so it was with some surprise when Dario pulled up behind us in his decidedly unostentatious Fiat Panda with his wife in tow. We were greeted warmly by a handsome, soft-spoken, medium-sized Mafiosi, who compulsively played with the cross hanging around his neck. After exchanging pleasantries and working out the details with Sbano he agreed to meet us on our last day to show us around the port and tell us a bit about what he does for a living.

Forty-eight hours later we find ourselves in another parking lot in the center of town, this time, ironically, behind the city’s municipal government building. We spot Dario and follow him through Gioia Tauro, which, as Sbano explains, was built around an ancient Greek necropolis. But I have a hard time paying attention because things have gotten noisy. Every car we pass seems to honk at Dario and most of the pedestrians wave and shout a greeting. Everybody knows Dario and he doesn’t leave town much, if at all. As a higher-up in one of Gioia Tauro’s two major clans, he is literally bound to his turf by ’Ndrangheta code, like Sergio. Bosses never leave town unless they are on the run or in jail and accordingly become threatening fixtures that most people greet out of deference because they are bound to see them every day at the grocery store, the cafe, the pizzeria, the bar.

We pull up next to a fish restaurant and Dario leads us inside and introduces the manager as a “friend of mine.” As we’re seated, Sbano tells me that this isn’t the right place to talk about Dario’s business, so I settle in for small talk and one more enormous meal, this time a plate of perfectly al dente, no-frills spaghetti and tomato sauce to start and a delectable grilled whole calamari main. And lots and lots of red wine.

As Sbano and Dario become increasingly immersed in conversation my mind wanders until I look up to see we have visitors. We shake hands with Al and Enrico who take their seats at the far end of our table and seem to want to talk business. Looking at Sbano, I can see their arrival comes as a surprise. Both men are extremely young, intimidating looking toughs. Al, a prematurely balding, welter-weight Italian Mike Tyson leads the conversation, while Enrico, his small, wiry driver and, as I would later find out, muscle, looked around the restaurant nervously, absently running his hand through his long hair. The next twenty minutes were the only time during my stay in Calabria that I felt truly frightened, and I spent most of it alternately staring at Al and Enrico and trying to avoid making eye contact. I understood almost nothing of what Al was insisting to Sbano except the names Spike Lee and Oliver Stone. Eventually, the two got up to leave and shook our hands, which came as a relief. Dario then explained that the duo were also friends of his and were there to ensure our safety, as well as to let us know that they knew who we were and what we did.

After lunch we left the restaurant and followed Dario along the beach and back into town, past derelict gas stations and the cracked concrete poverty typical of semi-urban areas in the Mezzogiorno, until we arrived at a small pizzeria owned by his cousin. There, to my initial fright, we were joined again by Al and Enrico for espresso. But this time instead of feeling threatened, the two were all smiles and did their best to make me feel at home, even giving me some fake body blows and pinching my cheek. Dario explained that wiry Enrico was a picciotto or soldier, which is the lowest rung in the ’Ndrangheta ladder. This is why he was constantly being asked to do menial tasks, like clean out the ashtray or fetch things from the car. Al and Dario both seemed to relish making Enrico do something and then break his balls about how he was doing it all wrong.

Across the street in a grey, unassuming apartment building is where Dario lives with his wife. He invited us to take a look inside. The spotless four-bedroom apartment was lavishly decorated with a wise-guy baroque sensibility, boasting various copies of Dutch Masters and courtly looking things. In the kitchen, a hundred dollar bill with the face of Al Pacino as Tony Montana was framed next to a Montecristo cigar, all perched atop a wine rack. While Sbano set up his camera to take some portraits of Dario, Al whipped out his phone to show me some pictures of his three pit bull terriers. In the meantime, Dario reached into his cupboard and pulled out some leather gloves and a ridiculously large handgun and placed it on the coffee table to use as a prop for the photo shoot. As Sbano started snapping away Dario soon realized that the gun wouldn’t do because of its engravings on both sides. And because it looked too intimidating. “It’s a gun for war,” Dario explained. “As opposed to just the everyday shoot out?” I thought to myself.

Concluding that it would be much better to use the unmarked guns located in a clan safe house down the street, we ended up driving to a nondescript, three-story apartment building. Inside there was only one door to a single apartment, with lots of space in the building that otherwise seemed to disappear. The small one-bedroom apartment was cold, austerely decorated and smelled of air freshener. On the walls hung a historical calendar of Calabrian saints and a generic picture of a palm tree paradise. Dario explained that this was where they stashed weapons, gangsters on the run and cocaine. He then told Enrico to fetch another pistol for the shoot. A few minutes later Enrico reappears with a gun shaped package wrapped in multiple layers of plastic and newspaper. The weapon inside was fully loaded. Enrico started to empty the clip onto the table with the gun pointed sideways uncomfortably close to my direction. Dario snatched the gun out of his hands and started berating him, then showing him how to do it properly in exaggerated motions with the barrel pointing towards the floor at all times. Enrico hands me a bullet and smiles. I nervously turn it around in my hands for a few seconds and give it back to him. For the next ten minutes Dario poses with the gun for the portraits, after which Enrico is instructed to thoroughly wipe all the prints off of everything we’ve touched. “Enrico’s got priors,” Dario tells me. “He can’t be too careful. Me on the other hand…” he laughs. “What do you want to know?”

Dario: Gioa Tauro is the largest commercial port in the Mediterranean, and of the circa four million containers that come through here a year, companies pay us a fee of a few euros per container for processing at the port, which in the end is a lot of money. But collecting money is not my job. I am a trafficker, and my clan controls an extremely large amount of the drugs that comes through Gioa Tauro. There are also two other main cities where Europe’s favorite and most expensive powder enters into—Siderno and Vibo Valentia. My other main job in the family is securing weapons. I’m the arms guy.

I became inducted into the ’Ndrangheta four years ago and now have a pretty high position as a contabile or treasurer, and this is something I’ve entered into for life. There is no getting out of it. But I don’t find my job stressful. Shipments come in from South America, and I just deal with it. As for the tarantella: yeah, it’s a part of ’Ndrangheta culture, but I think it’s become less important for the new guys than the old guys. But in Gioa Tauro we do things a little differently anyways, and often times have as many as five men dancing together in the circle. The tarantella for us still remains important, and when you’re asked to attend or dance, you do as you’re told. The last time I danced was about a year ago when a friend of ours was let out of jail. The fact of the matter is that it’s not so uncommon to not go to jail these days if you’re lucky. It’s not like I get up at dawn every morning and commit crimes all day. That’s not how it works. Some days I have very little to do indeed. I am usually working when something isn’t working. I solve problems—figuring out why a shipment is late or why something at the port isn’t functioning. You see, there is an extremely important distinction that I would like to make between the ’Ndrangheta and practicing ’Ndrangheta. The former has to do with being named an honorable man and being able to protect yourself and your family. The latter isn’t just about being in the ’Ndrangheta. It’s about proving yourself constantly. I didn’t get to be where I’m at because of my name, but rather because of what I am committed to doing. Part of that is being extremely generous without asking for anything in return.

If someone needs money, you give it to them without thinking twice about it. It is a classic aspect of being a man of honor: helping those in need, helping the poor. These are the seeds you sow to have them one day grow into trees of honor. I don’t speak so much about what I do and that’s exactly what keeps me safe. I like to think I have a pretty good sense of who could and would rat on me. And I’d like to think I’m protected by God, because I pray all the time.

Ciccio, former ‘Ndrangheta member member Despite having left his criminal past long behind, Ciccio was not an easy person to get ahold of. Numerous emails and meetings with mutual acquaintances proved futile in our attempt to speak to the small, heavily tattooed seventy-seven year old native of Cosenza. When we finally reached him on the phone through a friend a week after leaving Calabria, Ciccio was quick to reminisce about a time when the tarantella and the increasingly obscure and more brutal aspects of its rituals played a central role in his life as an ’Ndranghetista. This happened to be especially true for the now part-time baker, whose former status as a camorrista, or clan muscle, placed him in the center of brutal conflicts, which were occasionally carried out in the form of dance.

Ciccio: I was eighteen when I first went to jail for robbery and assault, and if I am honest, I had always admired ’Ndranghetisti, or “men of honor” as we often refer to them. I had sought their attention since I was a kid, but growing up poor, the only thing I could impress them with was my courage and ability to adhere to the principle of Omertà, or code of silence. That, I had a lot of, which is why almost immediately when I entered jail I was inducted into the ’Ndrangheta, which of course involved dancing a tarantella held in the prison yard. I got out a year later on good behavior and proudly reentered my small town as a man of honor. But that didn’t last too long and only a few years later I went away again for twelve years, again for assault, but this time it was a bit more serious.

By the time I got out in the mid-seventies, things in the ’Ndrangheta had changed. They called it “reforms”, but really it was all about the new garde literally killing off the entire old garde and instituting new goals, which revolved around ruthless killings and drug trafficking. I won’t say there wasn’t murder back in my day, but at the time, people warned you before you got killed so you had time to escape. But that was then. Anyhow, my boss went along with the changes, but I didn’t see the honor in it so I did something pretty uncommon: I asked to be released from my duties in the organization. He granted this, which happens extremely seldomly, and since then I have been degraded to the status of “contrasto onorato” and no longer have contact with my old clan. But I still have my ’Ndrangheta tattoos, which I am proud of and which are symbols of humility and pain and badges of honor. All of mine were done in prison by other Mafiosi. The enormous butterfly on my back represents freedom and its size is directly related to the length of my time spent on the inside. The snake is a symbol of my former status as a camorrista, and represents the fact that I can bite without warning.

Which brings me to the tarantella. For the ’Ndrangheta it’s much, much more than a dance: it’s our training ground and reflects so many aspects of our world. The circle of men represents the territory of our crew. The dance master is the boss, of course, and participants are there to show who can dance the longest and who has the fastest moves—just like in real life. For us, violence is as much a part of tarantella as it is part of the world of the mafia, and my skills in knife fighting, which I learned in jail, have come in handy on more than a few occasions. You see, in tarantella you employ the same tricks: in order to stay as far away from you opponent’s knife as possible you circle each other counterclockwise, but always face to face. This way you also protect your own liver. My most serious knife attack was actually planned beforehand by my boss. I cut a guy’s face and only afterwards found out that he was a boss from Sicily. My capo invited the annoying young don to the dance because he wanted to teach him a lesson. At the time I remember thinking, “I guess Sicilians don’t dance tarantella as well as us Calabrese.” But later on, and for the next twenty odd years, I worried he was going to seek revenge.

Ultimately, the tarantella is about entering a trance, an animalistic state. This is when you move instinctively, automatically, with speed and precision; looking, judging and reacting all happen in a single movement. This is when you have no fear, come what may. It’s the same state of mind a Mafiosi achieves when he’s planning or carrying out something evil.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2013/2014 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. A.J. Samuels and Francesco Sbano conducted the interviews. All photos are by Francesco Sbano.

Published April 02, 2015.