The article you’re reading comes from our archive. Please keep in mind that it might not fully reflect current views or trends.

From the Vaults: An interview with Bernard Sumner and Johnny Marr

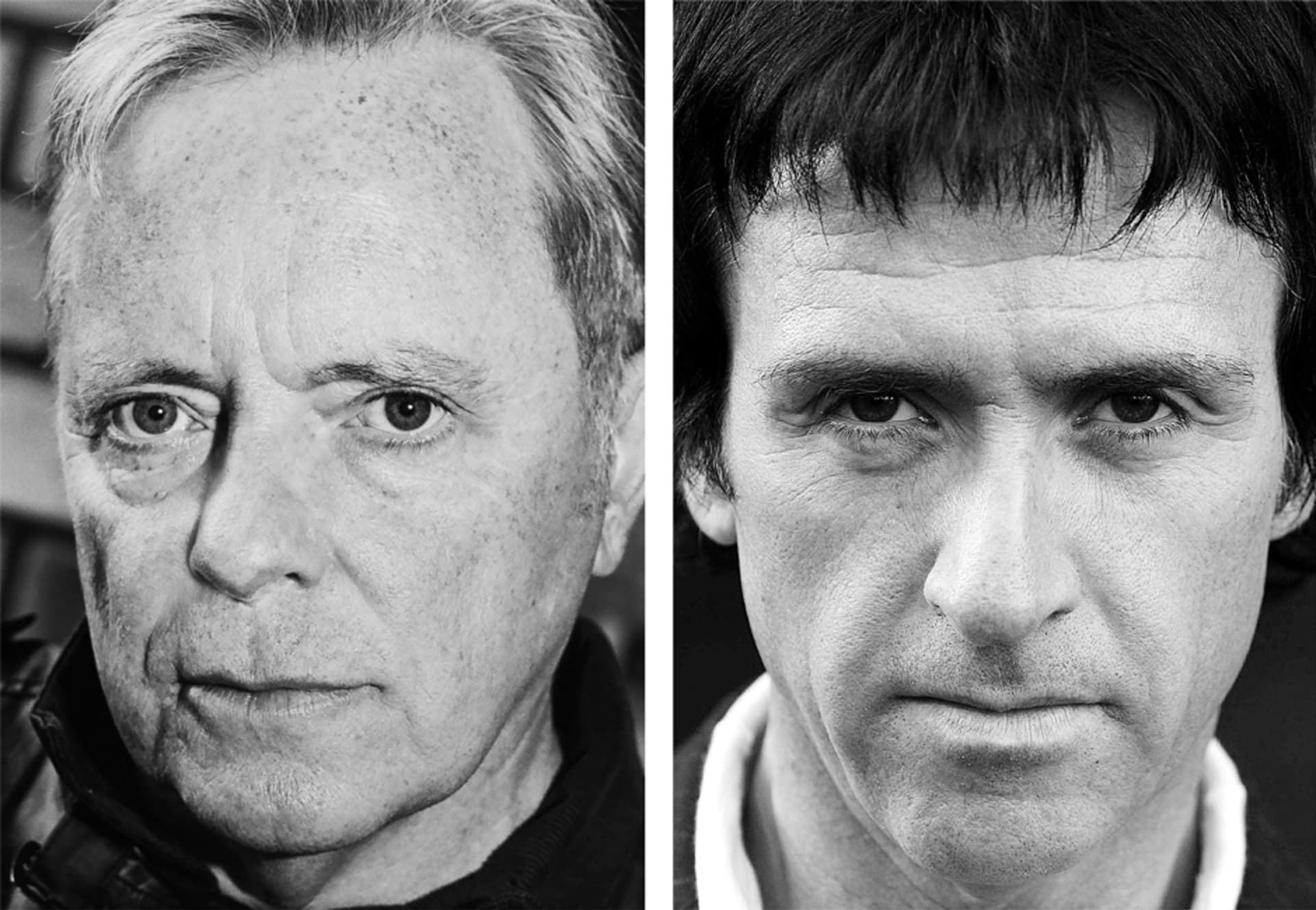

When two songwriting icons collide: In the latest edition of our irregular From the Vaults series, we present our editor-in-chief Max Dax’s 1996 interview with Bernard Sumner and Johnny Marr. The in-depth conversation originates from around the period they released Raise the Pressure as Electronic and is presented here in English for the first time. Photos: Bernard Sumner by Andrea Stappert, Johnny Marr (cc) University of Salford, 2007.

Max Dax: It’s remarkable that two musicians from Manchester with such unparalleled careers—with Joy Division and New Order and The Smiths respectively—have started working together and that the songs which have come out of the collaboration sound so different to the music you’ve made before. It’s much more club-oriented and has a techno feel to it.

Bernard Sumner: When we were in the studio with Electronic recording our new album Raise the Pressure, Johnny brought in an album for me called… Wait a minute…

Johnny Marr: New York Garage Trax?

BS: Exactly. That’s an album full of great club tracks. After all, we both love the Haçienda in Manchester, where they play music like that. If I were the owner of a record store for DJs in Manchester then I would have thousands of these types of records lying around in the store.

MD: What constitutes a song?

BS: If you think about what people like about the music that Johnny and I make, it’s the melodies and the harmonic structures in our songs. By comparison, it would have been too easy to just write a record full of dance tracks.

MD: Because these days machines make the process so easy?

BS: No, no, even simpler than that. In England you can buy copyright-free grooves on CD right off the shelf. One CD is full of drum loops, the next CD has dozens of bass lines, then there are CDs with piano jingles. You can sample whole bars of music made up of these hackneyed collections and put together an authentic sounding dance track. If you’re experienced and your hard drive doesn’t continuously crash, then you can write a track per night. However it’s not simple to write an original melody. In comparison to a melody, a groove is super easy to program. But even today it’s difficult for me to write a melody and a chord progression in a form that hasn’t been done before. Why is that? Because it’s difficult!

MD: It takes skill to write a melody. Would you describe it as craftsmanship?

JM: Yes, what we’re talking about here is craftsmanship. And emotions. And touch. A melody has to touch me and bring me to tears. That’s the benchmark. That’s what we’re searching for.

BS: Quite simply, it’s hard work to write a melody. Above all it means continuously throwing away ideas that you previously believed were exciting.

JM: It’s mostly craftsmanship, but there are also exceptions. Sometimes you find yourself in the right place at the right time. Sometimes an idea simply drops through the roof and hits you unexpectedly. Things like that don’t happen to you when you’re in the supermarket shopping or when you’re in the car driving to the supermarket listening to music—maybe sometimes when you’re driving, but rarely. I’ve been writing music for so many years and I must say that ideas only come to me when I have a guitar lying around somewhere near me, or a piano. It sometimes happens to me that I’m in the studio in the morning, overtired, working on a piece of music, and then I get all agitated and suddenly notice that I’m actually working on a completely different piece. Our song “Forbidden City” came about when I was working on another song, “Free Fall”. Those who know them will know that they are two very different pieces of music. We were programming, it was quiet, there was no music playing for one or two minutes and in this break I heard the song in my head with its whole chord progression, rhythm and refrain. I was worried that I would lose the idea, so I grabbed a guitar, plugged it in and let the DAT run. My only hope was that this magic wouldn’t disappear, I tried to not think about anything else other than this song that had come to me. If I had been outside of the studio the song would have faded away like a dream.

BS: Someone I know who writes books once said to me that he could touch-type with ten fingers at an incredible speed. He told me that this ability had enabled him, for the first time, to bash a thought or a sentence that he suddenly had in his head into the computer immediately without interruption—and then after that to type in the following sentence. He sometimes writes like he is in a trance, because the speed of his thoughts corresponds to the typing speed of his fingers. The thought of having to first labour to write a sentence before then thinking back to the other connected thoughts that he had really does him in.

JM: Unfortunately these moments in which songs suddenly appear out of nothing like dreams don’t really happen that often. You simply have to be there ready for it when they do. It’s a different way of working than simply being at the studio getting drugs and hanging around the pill table.

BS: But that doesn’t sound bad either.

MD: What comes first? The text, a line, a word? Or the idea to want to meditate about a certain topic?

BS: Most of the time it begins with a line that comes out of nowhere and straight away means something to me. Later, I make sense out of it and then find the rest of the words which turn that fragment into a song. When I write I try to go along with the flow of things. It only rarely happens that I sit down at the table with the clear intention of writing a song. Actually it was only that way with my confession, the song “Second Nature”. That was a case where I had the urge to summarize a lot of things that I’d been thinking about. In this song I imagine what it is like to die. When I stand face to face with God and I’m asked: “What have you learned in your life?” and “Second Nature” is my answer to that question. For me a song must always me a story, it must express something that I have actually been dealing with. But very often these are improvisations.

MD: In your song “One Day” there is line where you sing “It’s hard to face rejection / What used to be affection.” This has a wonderful effect—is it also the result of an improvisation?

BS: That’s a song that I would probably need longer to determine the real meaning of. Of course it is about love. That’s obvious. And about rejection. But what else?

MD: You don’t know?

BS: No. But look at this way: other songs don’t need any words, these being the dance tracks. When lyrics pop up in these, you can just relax and forget about them.

MD: But surely good lyrics don’t ruin a dance track?

BS: I’m coming ever closer to the realization that the whole point of dance music is to forget—it’s escapism. Forgetting about seriousness. A moment of freedom. Dancing to forget. You can work hard and concentrate all week because you want to reach or achieve something—at least in the best cases—and then at the end of the week you go to a club and want to forget about the pressure that these days have burdened you with. In this moment I use music to forget about the pressure, to suppress what is inside of me. The words in a dance track are generally only superficial. If I write a dance track then I don’t want to distract people from the rhythm and the flow of the melody. So in this way I approach different types of songs in different ways.

MD: Surprisingly, on the cover of the Electronic album Raise The Pressure there appear to be diary-like texts. With New Order you don’t communicate in this way.

BS: I wrote the notes that you can read on the sleeve of Raise The Pressure when I couldn’t fall asleep one night. Late at night I sat in front of my computer and wrote down what was going through my head. What I saw in the social realities of today, of the time in which I live. I wrote about how I see children, who are of an age where they don’t know what’s happening to them because they are not yet capable of abstract thought, being divided into two groups: one half of the children will lead a successful life, and will always experience affection, love, attention. The other half are sorted out and denied this.

MD: Are you talking about yourself? Were you sorted out in this way?

BS: In a way. On the other hand though, these children don’t just disappear into thin air. They continue to grow and become adults—and this is as meaningless as it is useless for society. What do these people do? They hang around and create problems for society. Society expects that these sorted out people will simply disappear into thankless jobs with McDonald’s or UPS. Of course a lot of them don’t do this and instead become criminals. Or they become psychologically ill because they very well know that they were denied the chance for a good life at a point when they couldn’t yet responsibly think for themselves. They simple weren’t allowed in. Our education system in Britain is responsible for a range of problems that our society has today, because it doesn’t treat all children with the same level of respect. It ridicules some of them. Our society is responsible for creating its underclass.

MD: Today you are the father of two children.

BS: I didn’t have these thoughts because I have children myself so much, but rather because some of my best friends are criminals. I asked myself why my friends have gone down this path, because these are, without exception, friendly and in their own way genuine, honest people. I would like to note that this particular worldview, and how it can be formulated as songs in my band with Johnny Marr, can not be transferred over to other projects. Songs are not innocent. We don’t do anything like this with New Order. That wasn’t ever possible. With New Order it was always about being passive. With New Order the lyrics follow a code. We have never made an active statement with New Order. We thought it better not to make observations or represent any viewpoints. For me it was very important with Electronic to step out from the protection that such a concept offers. It’s very easy to hide oneself behind the secretive or the vague. It can be so shocking to actually observe the world.

JM: We both still live relatively close to the places where we grew up. That means the crew which connects us to the places that remind us of our past is still around. But today we have more money. We are successful. I don’t live where I used to. I live close by, in a better area.

BS: I also live in a well-off area of Manchester. But I come from a very poor family. I can see the transformation. Today, the gap between rich and poor is bigger in England than in Kenya. That’s how things are in England. I’m talking about a division of society and I have experienced this division through my own life because I come from one end and have now moved around at the other end.

JM: The strange thing is that we don’t really fit in to either of the two classes.

MD: You said that with New Order it was about being passive. How do you mean that?

BS: New Order was escapism, clearly, above all it was a game of hide and seek. As the songwriter of New Order I never said a word about the lyrics that I wrote. With New Order everything is unclear and indistinctly laid out. It is intentionally unclear and misleading. You must understand that I was never a songwriter and never wanted to be a singer. I only became a singer because Ian Curtis, our singer, killed himself. We nonetheless needed to and wanted to continue, and the idea of replacing him with someone from outside seemed to us all disconcerting and even artificial. Through his suicide he interfered with my future, he changed my life. I had to suddenly do something that I had never considered. I had to change the way I looked at life. Up to that point I was always the one who stood in the corner and could observe the others. Even on stage. I was the guitar player, the observer. In this role I could also sit back in peace and register what all those around me were doing. I found that very interesting. As the singer you can’t do that. As the singer you have to face the people directly, you are the object being viewed and you receive the attention. That is the mental state of the singer and frontman. I had to change my worldview, my manner and as a consequence myself in order to make it as a singer and to be successful. My lyrics with New Order were therefore arranged as a way of protecting myself, so that no one, really no one, should know what was going through my head. I had to sing because it was my job. I was the only one that could steer the ship off of the reef that it had landed on with Ian’s suicide, and I therefore gave myself the right the hide myself.

MD: What are the New Order lyrics about if you talk about them from the distance of today?

BS: At a metaphysical level they were always about communication. Between people. Also and perhaps exactly when this communication didn’t occur or when it broke down. Furthermore, I would have felt open to attack if the communication had worked, if people had understood what was going on with me.

MD: But isn’t everyone who raises his or her voice on stage vulnerable?

BS: When I write a melody, a chord progression, that is something abstract. Even if this melody warms you, and hopefully it does warm you, it remains a sequence of guitar notes. The melody remains a feeling. A song lyric on the other hand is a literary concept; in my case it was the considered idea of a vulnerable human being. To say it positively: he who has nothing to say cannot hide or conceal this nothingness either.

JM: That’s very interesting for me to hear, Bernard, because, generally, other singers can hardly wait for the next time they stand in front of an audience and can let loose and have fun. I know what I’m talking about. Or they just can’t stop their thoughts flowing when they write lyrics, because they are caught up in a sexual ego trip or they just need to get their oh-so-important emotions down on paper. Those who work in such a way are, in my eyes, nonetheless entertainers. I don’t have anything against entertainers: entertainers have an enormously important role to play in society. People want entertainers because they want to be entertained. Every one of us needs entertainers. Bernard on the other hand works in a completely different way when he approaches his lyrics. Maybe it is actually due to fact that he only became a singer due to a tragic twist of fate. His story has always fascinated me right from the beginning. We both grew up and lived our childhood in a very hard English working class environment. Artistic expression was the last thing that we were encouraged to do by our parents. If as a youth you had expressed an interest in an artistic career, it was not supported. Today I can understand why it couldn’t have been any different: when you come from the working class you have to be able to provide for yourself financially and an artistic profession certainly didn’t provide the security you need to guarantee that. If you can’t answer the core question of how you are going to survive, then that means you have to pit yourself against your parents and in the worst case, leave them. And what then? Back then, where could you try out the artistic talent that you might have? I come from the north of Manchester, a very hard part of the city and when I was still a child we moved to an area in the south of Manchester that wasn’t quite so hard. When I told people that I came from the north, they were worried about me stealing their watches and wallets whereas for me it was like moving to Beverly Hills.

BS: What Johnny means is that where we grew up it was difficult to make the decision to be a musician or an artist because these weren’t the qualifications that would have allowed you to have a simple life. You had to be aggressive and defend your ground. Around us those were the qualifications that counted.

JM: In Manchester there are also areas of the city in which your hippy parents would start you with piano lessons at age four. They would then say to you, because they themselves would have loved to have been artists, “You will be an artist on our behalf. Go to art school.” In the north there wasn’t anything like that. I nevertheless knew that I wanted to be a musician. That wasn’t up for debate. And I think that this circumstance, that we had to struggle for the life we wanted, found good expression through our music, for me with The Smiths and for Bernard with Joy Division and New Order. You can hear it in the determination and the vulnerability of the music. The sadness that we had picked up along the way, and the doubt. That is perhaps the element that appeals to me the most about the music that I make. Even today, although I now lead a very privileged life. There are things one never forgets. I’m not referring to depression, but rather to melancholy and sadness. Depression just leaves me empty. Sadness on the other hand is a strong emotional feeling. Sometimes it is even necessary, because life is that way. Where I grew up the houses are from the Victorian era, they are black and run-down and they seem gothic. When I think back to my walks to school, when it rained there was something in the atmosphere there that was beautiful.

BS: Our band Electronic has a much less sad undertone than The Smiths or New Order ever had. We have also changed as people since those days. The worst time of my life was between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three. Back then my life was a never-ending procession of emotional storms. Thunder storms. Today I say to myself, if you survived this period, then you will survive anything for the rest of your life. What do you want from life? I want to be happier. And today I am a very happy person. ~

This interview was originally published in German in Max Dax’s Dreißig Gespräche / Thirty Conversations, published by Suhrkamp Verlag in 2008.