The article you’re reading comes from our archive. Please keep in mind that it might not fully reflect current views or trends.

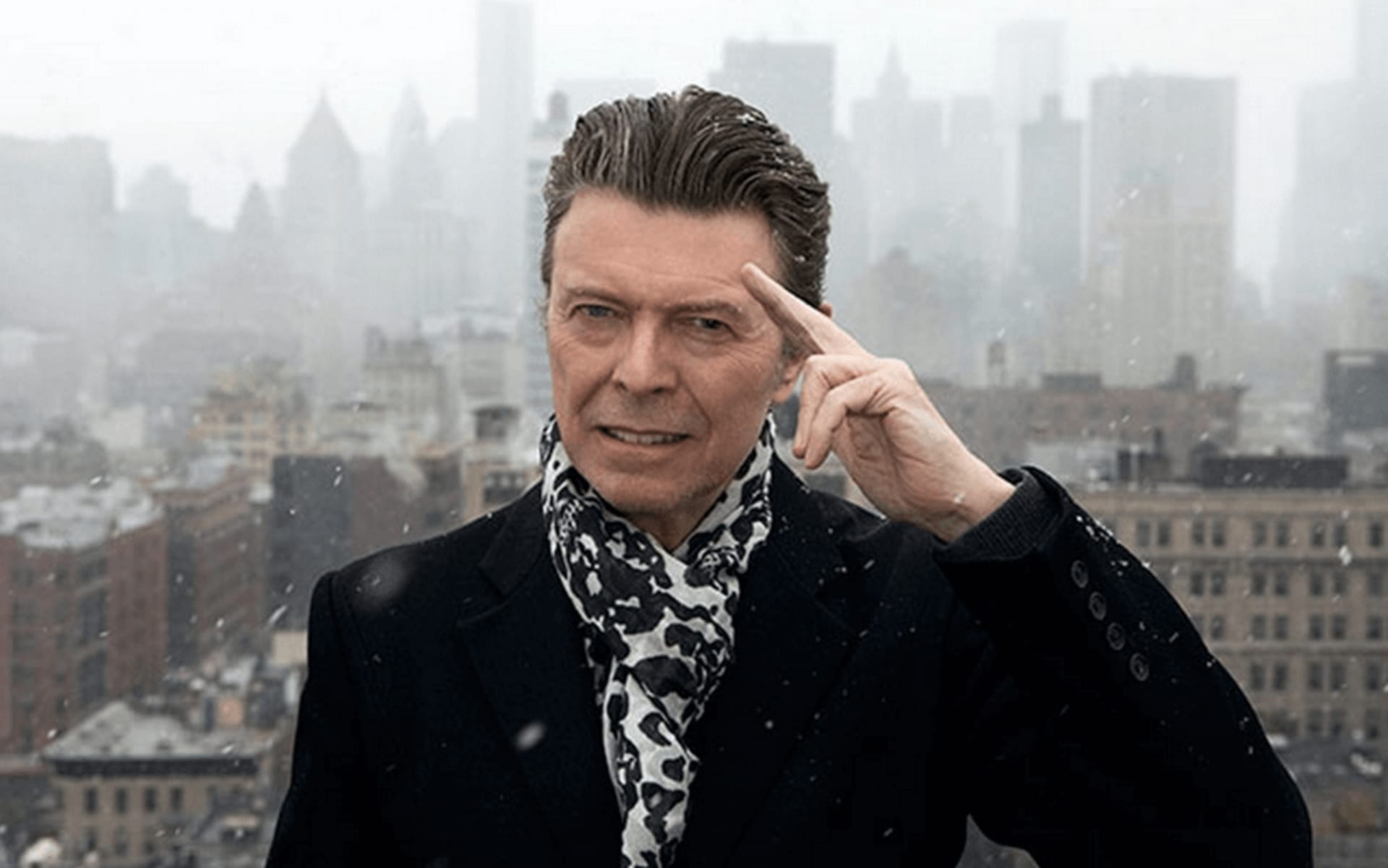

From The Vaults: David Bowie Interviewed

David Bowie’s sitting in the private room of an extensive suite of the Hamburg Atlantic hotel. The curtains are drawn, in the next room, a television crew is preparing a short interview. Outside the door, hectic activity, indoors: silence. Bowie is tanned and good-humored. He is in the Hanseatic city because of his sold-out concert in a small concert hall that evening. “How many tickets do you need ? You will come to the show, will you ?” He asks at the end of the conversation, after photographer Francesco Sbano is allowed to photograph for 45 seconds. Actually, he wasn’t allowed to be photographed, but Bowie made an exception. While we wait for Francesco, who rushes from the foyer of the hotel in the suite, I ask Bowie if he would sign an album of his band Tin Machine for me. He is surprised: “Most journalists didn’t like Tin Machine”. This conversation took place on 5 June 1997.

It’s nice to see you, Mr Bowie.

Do you know what I’d like to talk to you about? About how the coffee in Germany, even in luxury hotels, is disgusting. It tastes as if there is no pressure in the pipes or as if the water is chalky.

May I smoke?

But of course. I smoke as well. Camel Lights. Far too many.

I’ve got two good pieces of news for you, Mr Bowie.

Go on, young man! What would be the first?

Bob Dylan is…

… [interrupts] out of the hospital. Someone told me the breaking news just minutes ago. I have to admit I was nervous about his recent state of health. But everything should be OK by now.

You are a man who has continued to rediscover himself and his music. In this sense you are similar to Bob Dylan.

His comeback since the beginning of the nineties is simply spectacular and this positive tendency will continue, of this I am quite sure. His albums have a great class to them, even those albums where he is actually playing songs of long-dead blues singers. His writing, his song texts, leave me speechless. To a certain extent it’s a disadvantage for him that in certain circles today it’s not exactly fashionable to listen to Bob Dylan.

Do you really think that something like that bothers someone like Dylan?

No, I don’t think so. I am actually pretty sure that he is totally immersed in what he does. I mean, if he writes, then he writes. That means that when he writes, he writes for himself. And not for anyone else. I’ve also experienced that if you have an audience, then you have an audience. If you don’t have one, then you don’t have one. But when you have a task, a goal, something that you can lose yourself in, then you just do it. Then one isn’t really interested in being popular with one’s audience. Dylan is a writer in the original sense of the word: you write, but you’re not a supplier for consumers. Period. End.

Are you so far above everything that you don’t need to consider your audience? Are you also a person who only does what he has to?

I sometimes like to believe that. On the other hand, what I know with certainty is that I endeavour as much as possible to stay true to myself—to the halfway original ideas that I had when I first began making music, namely to find how music can be presented in different, more experimental and searching ways. And looking back I think that I have done pretty well at staying the course when measured against the goals that I set for myself in life. And this doesn’t really change much when I consider my ambition for the future. I like my work, I like the music that we write and play as a band. I think we’re doing it right. I mean, right in terms of what we want and what we consider right, naturally.

If we can come back to Bob Dylan once more, his texts and his music, indeed his entire presence, has become more serious or one could even say more religious or more spiritual, without having needed to produce explicitly religious albums…

You’re right there, even if Bob Dylan has always had a very strongly developed sense for the metaphysical. I am furthermore of the opinion that he has from the very beginning been on a spiritual search that has consumed his entire energy and given his whole being and his work such a philosophical dimension. I can only too well understand that throughout this search he has encountered different religious structures that he has absorbed into himself and which have at different times flowed into his work. One of the forces that have always driven me both as an artist and as a private person has been the search for a reason—a rational, comprehensible reason for my existence. That is an intensely deep type of quest that forcibly leads one into a religious-spiritual examination of oneself. What I actually want to say is the following: if one sees this spiritual search for meaning as one’s mission in life, as Bob Dylan does, then it can turn into an obsession that, on the other hand, might take away the innocence one had before when one led a more unassuming, naïve and unburdened life. In other words, one perhaps isn’t as influenced by television and other fast moving things as one was previously. These are the important questions. That’s exactly how I see things as well and I’d like to emphasise that. I find much more pleasure in this self-examination than I do in other things.

The reason that I persist is that I have the feeling that there are a large number of similarities between yourself and Bob Dylan and that there is possibly some kind of even deeper level of respect between you two than is usually the case. Both of you have enriched musical history in several genres. Not very many musicians have so much creative drive! Another similarity between you and Dylan is that you are both very popular. A great deal of people would recognise you or Bob Dylan on the street. That surely has an effect, or not really?

You’re totally right, but there is a third similarity between us both: we actually have never sold that many records. For both of us it is the case that our work, our songs, are much more well known than would be usual relative to the number of recordings we have sold. I find that strange and noteworthy at the same time. We have both written songs that are extremely well known around the world, but hardly anyone has them on record at home. That is really unusual. That might be because we have both been far more occupied in our lives with changing things, exploring the textures of music and finding out exactly what music is capable of doing rather than simply writing songs and then sitting back comfortably and attaching ourselves to this or that trend. I’d go so far as to say that our task was and still is to explore the depths of music and to alter the shape of music. Bob Dylan has said about himself that he “was chosen to be a performer”. I think that says everything. We have changed and expanded the vocabulary of music and we have thrown new facets into the great big pot of musical history. And the songs we have written can be considered as the proverbial splinters that fall when wood must be chopped. I suspect that the majority of people out there would also see it that way: they have watched on with interest at our experiments but have preferred to buy the songs of other artists who have set about turning the results of our research into more refined forms.

In this way you are characterizing your songs and the songs of Bob Dylan as a kind of common property?

Yes, it appears that way to me. Having said that, it fills me with a sheer unfathomable happiness that it is that way. I am not complaining. I have a great sense of joy for example when I see or hear bands out there and I notice that they consciously or unconsciously are adapting things that I was the first to do so many years ago. That’s when one has the sweet realisation that one has changed music. That is immensely satisfying, having such a feeling. That all being well, this feeling of happiness hasn’t helped me in the slightest to answer the questions that I carry around with me. I sometimes get the impression that in this regard I haven’t taken a step forward since I was 19.

But if it wasn’t that way then everything would be much more complicated, right?

I’m also afraid that may be so. I would even say that although I would describe myself as driven I devote far less energy to actually answering my own questions. I have actually learned to live quite well with my unanswered questions regarding meaning. It’s good to keep asking these questions; finding the answers—if they actually exist—is less good. That’s probably the road to madness and I can see a stretch of that road already behind me and I know now that I don’t need to run it down so fast anymore. I can give you a comforting piece of advice that the idea that everything will remain unclear until the end is ultimately very, very beautiful. At least that’s what I have to say at fifty years of age.

You spoke before about the texture of music, that you sought to try and change. In the past you have often characterised yourself as an eclectic. Is that a type of formula that works—as an approach and as a way of viewing things?

I would say yes.

Music itself has changed. Today there is club music where previously there would have been jazz music. There are many variants: house, techno, drum‘n’bass…

… don’t forget electronica, as it’s called these days. That is to say the music that has developed out of the old structures, by which I mean German bands such as Cluster, Neu!, Kraftwerk and Faust.

Along with the song, today the structure, or the track, is considered to be almost as important. This is what you find with club music. The melody and words of the song are becoming in this sense less important.

Now I don’t know if that applies so much to the music that I make. In my music there is a large degree of ambiguity. If one wanted to compare my music with landscape painting, then intuitively I would say that my holding onto melody possibly belongs in the nineteenth century. I quite simply like good melodies, you can say to that what you like! It may appear that I have been left standing in a passing phase. I am still inspired today by the earlier heroes, particularly Neu! and Magma. The latter are a French band from the seventies who worked in a similar way to all the bands from Dusseldorf. This spirit, this special zeitgeist that these bands created, still fascinates me! It’s comparable to the influence of The Velvet Underground in the sixties. I’m talking about free thinking, the search for new, free forms. I’m talking about how these boys understood to search for chaos and to use it in a positive sense for their own ends. Most people perceive chaos as something threatening. I, on the other hand, find it wonderful when new forms of expression become apparent to me during my attempts to give structure to chaos. One day it dawned on me that it was or is exactly these things that have distinguished the late twentieth century! Yes of course, I said to myself: that’s how our world is, that’s how it feels! That was so to say the pre-postmodern, back then in the seventies. This time, and above all the leading artists, understood that everything that has ever been on this earth and everything that has ever happened was at the same time equally important. By the way, that drove a lot of people crazy—that they no longer knew what should have priority and what shouldn’t. Everything was important, and therefore everything was either difficult or simple, depending on your way of viewing this matter. Most people however feel scared about this. That is also the reason why most producers lock themselves into one style and reject the others and why many people perceive their existence as a free fall through our age—without that reassurance that they would consider absolute. I, on the other hand, am of the opinion that this state of things is liberating, because it means that we can create our own future! We have all the ingredients in front of us ready at hand that we need to create something new. The only thing that is stopping us is the insecurity that comes with freedom, but which scares us.

I promised you more good news…

People have started to like good melodies again?

The good news is that exactly that music you have been talking about—the experimental German music of the seventies—is experiencing something of a renaissance at the moment. I have brought you a present, which is the long lost Tracks & Traces CD by Harmonia ’76 that was originally recorded in 1976 but never saw the light of day—until today.

Yes, that really is a positive development. I’m a fan of Harmonia ’76 and I can hardly wait to see what will come out of this all. It’s good that all the important records, including the Neu! records, are now being re-released—and on vinyl. Is there a shop in Hamburg where one can buy old vinyl from the late seventies? My collection of German electronic records would be immensely richer if I could find one of two particular records. Do you know, these records are something like my memory, my cradle and my adolescence all put together. They have left their mark on me, opened my mind and heavily influenced me. I respect them and I’m amazed by them.

Do you know Kreidler? I’ve brought you a CD called Weekend by Kreidler. Like Neu! and Kraftwerk, Kreidler also come from Dusseldorf and are perhaps something like the heir to these bands.

That’s a beautiful cover. A magnolia in a field. By the way, I’ve heard a lot about Kreidler, and only good things. In the seventies there were so many great bands in Germany that worked very intelligently and inspired to dissolve musical boundaries. Most people still think that there was simply Kraftwerk. Naturally. Kraftwerk are superhumanly good. You can describe my respect for them with the word “absolute”. But there were others, many others, that didn’t have the luck to become so famous so quickly like Kraftwerk did, but nonetheless made equally interesting music. They ended up in the rubbish heap of history, because, as we say in England: “The winner is always right!”

The drummer from Faust now drives a taxi in Hamburg. But he doesn’t complain about it.

Do you know Edgar Froese? He was part of Tangerine Dream, but I’m talking about his solo albums, which I can highly recommend even if they sound completely different to all the other records that we’ve been speaking about. I very much absorbed the sound of the early German electronic music from the seventies. When I speak about influence, I’m not just talking about the soundscapes and the musical moods. I’m talking mainly about rhythm and how these Germans back then managed to knock together such breathtaking beats out of their synthesizers. The fascinating thing was and is that these Germans developed these beats out of South American beats, which is why this music appears to have such an unbelievable amount of soul although it was created with electronic instruments.

Are you referencing to tracks like “Autobahn” and “Showroom Dummies” here?

Exactly. And I could name a few others. These Germans adapted these black beats and in a surprise manoeuvre adapted them into a very European form of expression. If you ask me, that is typically German. And I am furthermore someone who is interested in every mutation, someone who meticulously follows every mutation. I like beats. I also like rock. And I also like my band, Tin Machine. Back then I worked together with Tin Machine on a return to the embryonic fundamentals of rock music, simply in order to clear my head for a while. And in order to breath life into my being as a musician again.

Do you still aspire to be innovative today? Or is it more the case that when someone else is innovative, you feel attracted to this person and that you can absorb what this other human has to offer, like a sponge?

Oh, it’s more the latter. I am he who quotes, I am the sponge that absorbs, I am the shepherd of my own self. I am also very careful regarding the use of the word “innovative”. This word, particularly when one uses it to describe one’s own work, indicates a certain amount of arrogance. I would rather aspire to be someone who always tries out new things—both alone and together with other people. Ultimately I try to do the things that fascinate me. It should be added that I have actually always felt infected and inspired by the cultural context that I have found myself moving around in. It was that way in Berlin, it was like that in America and it is like that in London. For me that is the main reason for travelling, to absorb these new sensations, to search for oneself in others, to actually become a part of new environment. I can accept that in my case these are almost obsessive traits. And of course all of this has a way of finding itself into my music. That is what I would describe as my sponge-like qualities. In short, what comes out of me is hopefully original and hopefully possesses the integrity of a man who has an opinion. But

Because you don’t like to follow the expected path but rather confront people with something new?

Not necessarily anymore. I have always been interested in club music. And what particularly fascinates me today is that drum‘n’bass, techno and also electronica are made out of new structures—they distance themselves from the common pop song. You could also see it this way: that drum‘n’bass is like the material of my suit. The material has a structure, a texture, it feels different to the material of a different suit. I’m talking about when your finger runs over the material. The cut of the suit gives the structure stability and defines whether the material will be rescued over into a new age—or will be forgotten, lost in the past. In this sense I am the tailor who chooses the materials out of a collection, touches them and feels them with his senses and then cuts.

Miles Davis once said of you: “Bowie? Isn’t this the guy who dresses like a woman?”

Nowadays I prefer suits because they’re so comfortable. They are like a sleek and highly effective coat of amour—the amour of modern man. In his time William S. Burroughs introduced me to the suit. He taught me that your fellow human beings treat you differently if you wear a suit. He who wears a suit comes to sense a different, pleasant side of life. I can only recommend it to others. Beyond that, it doesn’t need to be an extremely expensive suit—back then we bought suits in second hand shops in Brooklyn for a few dollars. The important thing is that it fits properly. There is no difference between my clothing style and my music. When I make music, I am very conservative. Like I said, I love good melodies, and melodies are simply handicraft. But sometimes I get the impression that these days even the search for the new, for innovations, is seen as conservative.

How do you deal with the fact that pop and club music are perceived as music that is made and consumed by young people, that it is perhaps even adolescent music?

That is the mystery of my life! The simple explanation for this is that unfortunately the mind goes in one direction but the body goes in another. Thoughts, the mind and consciousness stay young and open, sometimes I even get the impression that thoughts don’t age at all. In my eyes, disappointment and cynicism are the spiritual or intellectual equivalent to bodily deterioration. The mind and the body get older but not necessarily at the same speed. I suspect that it has something to do with brain cells. But I don’t think I’ve reached that stage yet. I think as long as we’ve got enough cells in our brain that our minds don’t play tricks on us. All I’m concerned about is that I continue to have fun with my profession. I enjoy playing concerts. I’m happy that I mean something to the people who come to my concerts. Of course I suspect that I will give up playing concerts as soon as my bodily functions no longer allow it. ~

This interview was originally published in German in Max Dax’s Dreißig Gespräche / Thirty Conversations, published by Suhrkamp Verlag in 2008.

David Bowie opens to the public May 20th at Martin-Gropius-Bau and runs until August 10th.