The Definitive Oral History Of Berlin’s Fuckparade

The unlikely story of how Berlin's '90s gabber scene united to create the city's most intense street party.

Berlin may be known for its wild techno marathons, but for the past 21 years, the city’s most intense street party has been soundtracked by gabber. Developed from the scene of gabber heads that used to congregate at Berlin’s notorious Bunker club, The Fuckparade is a yearly event that was founded in the ’90s as a response and counter protest to the more well-known Love Parade—in the eyes of the Fuckparade organizers, it had become a mass event and a bloated commercial mess. The Love Parade has since left Berlin and has ended in tragedy, but despite having lost its arch nemesis in the 2000s, the Fuckparade still persists to this day.

In this feature, Sven Von Thülen, Telekom Electronic Beats’ senior editor—and author of Der Klang Der Familie, the definitive history of early Berlin techno culture—met up with many of the key figures of the era to create this definitive oral history of the Fuckparade.

The speakers include:

- Trauma XP: Frankfurt-based hardcore and gabber DJ who founded the Fuckparade

- Panacea: Hardcore and drum & bass producer who performed at the first Fuckparade

- Xol Dog 400: A key player in the Berlin hardcore scene, a one-time Bunker resident and longtime core Fuckparade organizer

- Moog T: The Fuckparade’s current main organizer

- DJ Fater: A Bunker regular, gabber DJ and early Fuckparade team member

- Wolle XDP: Founder of “Tekknozid” raves and hardcore techno-focused party series “Hartcore” at Bunker—also a short-time Fuckparade organizer

- Mo: Frequent Bunker and Fuckparade attendee. She is also a DJ, producer and integral member of Berlin’s Electro Music Department label

- Disko: Former E-Werk resident DJ and Love Parade press spokesperson from 1998 until 2000

Chapter 1: One Family

The story of the Fuckparade can’t be told without turning first to the Love Parade. Originally started in 1989, it reflected the euphoria and spirit of unity felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Sonically, it was also a moment in time when electronic dance music’s scenes were under a single roof. Techno, house rave, breakbeats and even gabber were all a part of one all-encompassing community. This was reflected in the music at the Love Parade.

As time progressed however, the genres began to splinter off into separate communities. Gabber, with its dark humor and punkish aggression, was one of the early parallel sonic universes. This separation could be felt at the Love Parade, where the gabber community felt itself increasingly unwelcome as the parade became more commercial in the mid ’90s.

Xol Dog 400: I’m originally from the EBM scene. When techno got started, it felt like being part of something new. It was the same thing with the Love Parade. You’d be really excited for days before it. But after the third or fourth parade, I was done with it. I already had the feeling that it was going in the wrong direction.

Trauma XP: In order to hear the music that I liked—techno of the harder variety—I always had to travel from Frankfurt to Berlin. In 1991, I heard Tanith at Tresor. His sound was so dark and mean, even though it wasn’t very fast. I didn’t know anything like it until then.

Xol Dog 400: Everyone was still together in 1991 and 1992. Tanith was one of the spearheads of hardcore techno at Wolle XDP’s Hartcore parties when the Bunker opened. We were practically a family there. Then that family split up—not because of musical styles, but based on the question of what is marketable and what isn’t. It soon became obvious that gabber wasn’t accepted.

Trauma XP: It was the same thing in Frankfurt. There was a brief period when even Sven Väth would play Rotterdam Terror Corps’ “No Women Allowed”, but that was really only for a very short time. Maybe the reason was because Torsten Fenslau died in 1993. He always played faster stuff. After his death, all the “normal” techno DJs concentrated on trance and “intelligent techno”. Gabber was considered lowbrow.

Wolle XDP: I liked the first gabber records and the harsher tracks by Aphex Twin. Back then it was great when someone played something like that to kick up the intensity for a while. But if that kind of stuff was played for the entire night it put me in a bad mood. It’s still the same today. If the attitude toward life is only about being crass, then it gets boring for me.

Xol Dog 400: The bigger the Love Parade became, the further it moved away from representing the entire scene. Instead, its development accelerated the commercialization of techno. The harder genres soon died out because you couldn’t get Camel to advertise next to that stuff. And with the increasing prices to register a suitable float and to participate at the Love Parade, the gabber and hardcore scene was pretty much gentrified out of existence.

DJ Fater: I’m a disappointed Love Parade attendee. At some point, it all just grew too big and overwhelming. It became like that from the moment it moved to Straße des 17. Juni from Kufürstendamm. The fact that there was no longer a dedicated gabber truck pretty much finished it off for me.

Wolle XDP: At some point, the Love Parade cozied up to the majority—to mainstream society. That wasn’t necessary at all. I had just seen They Live for the first time, and I could perfectly imagine the Love Parade being in that film. When the procession with the big Camel banners rolled past, it was like you could put on the glasses from the film and see that half the people are hypnotized and the other half are aliens.

Mo: In 1993 or 1994 we drove in the Love Parade with a flatbed truck from the Elektro Club. That was really funny. The turntables weren’t mounted on shock absorbers, so DJing was rather difficult. Every set involuntarily ended up sounding like breakcore. At the time, I thought that techno—as a contemporary historical phenomenon—was something like a political movement. The music brought people together, and in its way helped them relate to each other. But since there was no clear political message, I didn’t really view the Love Parade as political, per se.

Trauma XP: The Love Parade wanted to be a political demonstration, and it had a huge reach up until 1997 at the latest. It was broadcast live on television, and at some point the whole world was watching Berlin on that weekend. And the only thing Motte said was: “Great that you’re all here. It’s great that it’s all so peaceful.” I thought that was pretty weak. Peacefulness isn’t an achievement. That’s called civilization.

Wolle XDP: I have always been a politically-minded person. At the few meetings I had with the Love Parade people in the early ’90s, when I still felt part of it, I always asked why they didn’t use all the attention to address specific political issues. They didn’t want that. As a recent East German, a slogan like “peace, joy, and pancakes” didn’t appeal to me.

Xol Dog 400: What remained was the picture of an apolitical crowd who had no problems with being dragged along by the cigarette industry.

Mo: This absence of a clear political position was, in my opinion, also an important reason why the number of participants grew so much.

Chapter 2: The Bunker

Berlin’s gabber scene coalesced around an illegal venue called Bunker. Even by the city’s own standards of industrial grandeur, the construction of the club’s building stands out. Originally designed by Nazi architect Albert Speer, it’s a massive high-rise bunker that modelled on a renaissance palazzo. A concrete monolith, its small rooms and low ceilings lent its parties an intense and claustrophobic feeling. It was there, too, that legendary Berlin men’s fetish party SNAX got its start.

In the book I co-authored, Der Klang der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the Wall, the club’s owner, Werner Vollert, shared his reasons for opening the club, “It had to go in the hardcore direction, away from the gay dance and party techno, towards aesthetic liminal experiences with music. Where does noise begin and music end, and what’s still danceable?“

Small wonder that the venue quickly gained a reputation as the “hardest club on earth”. It attracted a devoted fan base, and yet it wasn’t to last, and by 1996, the venue closed, leaving an entire community of hardcore fans without a space to call home.

Xol Dog 400: Around 1995, there was an idea in the gabber scene to do something of our own during the Love Parade weekend. We already had the impression that we were no longer welcome. The final impulse was when the Bunker closed in the summer of 1996.

DJ Fater: The Bunker was the home base for all gabber heads in Berlin. The building itself was very impressive. Noise complaints weren’t an issue there either. There’ll never ever again be a club like that, at a location like that. I was there for the first time in 1993, at one of the first Gabba Nation parties. I was 15. As soon as I got in, I asked about DJ Cut-X. “He’s back in jail again,” was the answer. “Again?” I asked. “Yes, it happens a lot.” That’s why people had warned me about the Bunker.

Wolle XDP: Back in 1993, after I’d finished my brief collaboration with Wolfgang Vollert, the owner of the Bunker, I no longer had anything to do with the place or the people there. What developed after my departure was way too heavy for me. At the time, the techno and gabber scenes in Berlin were parallel universes that had little to do with each other.

Mo: The Bunker was a tiny island in the midst of the techno-bustle. E-Werk and Tresor were definitely bustling. They were tourist attractions. Sure, there were still cool parties, but you couldn’t actually go to a place like Tresor after 1997.

Xol Dog 400: The Bunker was special. Not only the building, but also the fact that the same building also had the Ex-Kreuz Club–a fetish place–which was also home for Tanja’s Nachtcafe, a more of a bourgeois cabaret event series.

DJ Fater: In the garden, there was the Ex-Kreuz Club, which was a fetish club. We gabbers would turn up there every week. We were there in our black terror hoodies, and then there were the people in bondage gear sometimes being dragged around the yard on a leash.

Xol Dog 400: A lot of different people came together there. Sometimes it was pretty funny. When coming out into the yard from one of the techno parties, it was possible to come across fetishists who led their sex slaves on the leash through the vicinity, and at the same time there were older couples who came from Tanja Ries’ cabaret. That was pretty unique.

Mo: I loved going to the Bunker even though I wasn’t there regularly. It was simply an experience. The gabber scene, and the Bunker in general, was very much a man’s world. But that didn’t bother me.

Xol Dog 400: For us, the Bunker was more than just a club. Later we attached climbing hooks on the outside of the building, and then we’d meet there in the afternoon to climb and drink coffee.

DJ Fater: Besides the Box, in Hamburg, there was no other gabber club anywhere else in the world. In that sense, it was an absolute privilege.

Xol Dog 400: The Bunker was my living room for years. And it was for many others, too. When it had to close, it was clearly the end of an era. Something was happening that couldn’t just be undone.

Trauma XP: There was word of another “very last party” at the Bunker. It was illegal, of course. The operator Werner Vollert still had the key, and I was booked there again at the end of 1996. So were Xol Dog 400 and Cut-X from Gabba Nation. But the cops found out about it beforehand and turned up en masse to prevent the party before it even started. So then Xol got into his car, turned his stereo up loud and people started dancing, right in front of the Bunker. The police made three announcements for us to clear the road. After the final call from the police and the threat of violent eviction, everyone left.

Xol Dog 400: What remained was frustration. And with it came a certain politicization, because we realized that the Bunker was gone and that other clubs had also gone or were under threat. It became clear that the anarchic conditions after the wall came down couldn’t last forever. It was no longer possible to occupy these forgotten spaces for ages without anyone taking a closer look. But when it finally happened, the frustration was immense. And it was clear that it would hit the harder non-commercial forms of techno first. Berlin got cleaned up.

Chapter 3: The Hateparade Is Born

The Fuckparade’s earliest incarnation was actually known by a different name. After the Bunker closed, DJ Trauma XP dreamed up a new kind of politically-oriented festival called Hateparade. In conceiving of it, he looked at Frankfurt’s Nachttanzdemo, a demonstration with soundsystems and ravers, that happened spontaneously in 1995 for the first time, opposing that city’s repressive stance against illegal parties and recreational substances. Trauma XP’s idea was to create something similar in the German capital.

Trauma XP: A few months later, I was booked at the Eimer and slept at Cut-X’s place. After the party, we sat together and philosophized about how shitty it was that the Bunker had been closed and that the final Bunker party was prevented by the cops. And also that there was only shitty music being played at the Love Parade. Then came the idea: If the Love Parade is a demonstration, then let’s do a counter demonstration.

Xol Dog 400: At some point, Trauma XP announced that he would organize a Hateparade. At first, I was skeptical about the name. I didn’t think it was good. And I said that clearly. For one thing, for me it was too obviously a response to the Love Parade. On the other hand, it provided a point of attack that wasn’t actually necessary.

Trauma XP: It was somehow obvious that the counter event to the Love Parade would have to be called the Hateparade. Apparently, the same name had been used in 1996 and 1997, during Hannover’s so-called “Chaos Days”, during which punks and police clashed. At the same time, a flyer turned up calling for Berlin to be laid to waste in the context of a Hateparade. Of course, the police were alarmed and freaked out when I registered the demonstration. They really thought we wanted to smash up Berlin.

Xol Dog 400: The press jumped on it right away. They didn’t understand it at all. They didn’t want to understand it—not even the humor. For example, the Love Parade logo with the hand grenade instead of the heart in the middle. Even a lot of the Love Parade people thought that was funny. But the press, as outsiders, couldn’t make the connection. They saw it as a call for violence.

Trauma XP: On our flyer we wrote: “We oppose the sale of the Scheunenviertel district.” Today that’s known as gentrification. It was clear to us that more clubs would suffer the same fate as the Bunker. We wanted to point out that such things don’t happen in a vacuum, but that they are obviously linked to the general trend in rental prices.

DJ Fater: I don’t remember how I first heard about the Hateparade. It was probably at a party. At that time, there were still a few gabber locations like Grüne Hölle, a squat at Spittelmarkt and also the Stellwerk in Friedrichshain.

Trauma XP: Apart from Xol-Dog, the people in Berlin were pretty flakey at the beginning. They liked the idea but were unable to implement it. I bought a book about German demonstration law and called the assembly authority in Berlin to ask what we had to do. They told me I should just send them a fax. I did so, and with that, the Hateparade was registered.

Xol Dog: I knew that quite a few people would come—the entire core audience from the Bunker, for example. I had expected maybe up to a thousand participants, essentially the Berlin hardcore and gabber scene. When the time came, not only was I surprised that were there many more than that, but also that a lot people had come from other cities.

Chapter 4: The First Year

On July 12, 1997 the first edition of Hateparade took to the streets. The starting point was the then-closed Bunker. A couple of thousand gabber heads, punks and other techno misfits danced through Berlin’s Mitte district protesting against gentrification and the commercialization of the Love Parade, which was happening simultaneously at the nearby Tiergarten park. In its second year on the bigger route, the Love Parade hit a new peak and managed to attract one million ravers from all over the world under the motto “Let The Sun Shine in Your Heart”.

DJ Fater: At the first Hateparade, the entire gabber family was represented. That was the focus. It was uncommercial. You arrived there and immediately said: “The right people are here.” Everyone was dressed in black terror hoodies as far as the eye could see, and there were punks everywhere. There were always a lot of punks around at gabber parties. The Mutoid Waste Company drove trucks with their scrap steel sculptures that spat fire. That was Berlin.

Moog T: I moved to Berlin in 1997. A friend who wanted to write a political science paper on subculture and techno dragged me straight to the Love Parade to conduct interviews with the ravers in their furry gear. But that wasn’t especially satisfying, so we went to the Hateparade to try our luck there. The interviews didn’t work out because we just joined in with the crowd and danced. That was the beginning for me.

Mo: The stance against the Love Parade immediately appealed to me. So I went to the Hateparade with a number of my friends; most of whom had nothing to do with the Bunker at all. It didn’t really represent me, either, but it definitely stood for the underground—for all the little clubs, party crews and sub-scenes.

Xol Dog 400: The starting point was the Bunker.

Wolle XDP: For the established Berlin techno scene, the Hateparade was actually a no-go. The gabbers were considered to be the nasty kids.

DJ Fater: We were always the bad guys: freaks with terror hoodies. Gabbers from all over Germany met for the first time at the Hateparade. You could really see that the scene was networked even without the Internet. It was impressive how many people turned up. At the Bunker, you could never see anything. It was never clear if there were ten people in the place or a thousand people. That gave us courage. Also, the scene: you noticed that there were actually quite a few of us.

Trauma XP: I asked Cut-X if Gabba Nation would do a truck. At the Hateparade, we had five trucks and also a truck with a punk band.

Panacea: Back then we traveled by train from Frankfurt to the Hateparade. Achim Szepanski of Force Inc Music Works arranged and paid for the truck and the sound system. Achim had a very determined political stance. He thought it was important for us to be part of the Hateparade. At the time, everything that didn’t fit in with the concept of love–or commerce–was no longer wanted at the Love Parade.

Trauma XP: There were also techno-hippies there and people who you could find today in the free tekno and teknival scenes. It wasn’t just gabbers. It was a lively mixture.

Panacea: Visually, the Hateparade was a bit more martial. If you’d have put people like Xol Dog 400 and all the Bunker crowd in the Loveparade, all the flower ravers would have thought that Germany’s GSG 9 had come to shut down the parade.

Trauma XP: There were five hundred people with black terror hoodies on, all of them looking grim. Some looked like Nazis, others like radical punks. It was a very different spectacle from the flower ravers at the Love Parade.

Mo: Of course, the first Hateparade was fairly modest in size. The trucks were more like those from the Robben & Wientjes flatbed rental fleet.

Trauma XP: I had rented three trucks from a squatter collective in Friedrichshain, one of which was a Russian Ural. They were these giant things that you could load a sound system onto. I had hoped that if all the DJs would donate fifty Deutschmarks, then it would end up covering the costs. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. They all played great, then said their friendly goodbyes. I got stuck with the costs.

Mo: It all seemed very improvised. There was no big master plan. It was more like something that was dashed together.

DJ Fater: It was pretty chaotic. Nobody really knew what to do. And some of the people on the trucks also didn’t. The cops were totally overwhelmed. We were totally overwhelmed. There was a huge construction site at the Tacheles. No one had thought about that. When we stood in front of it, we just moved the fences aside and drove through with our trucks and the whole parade behind us. That’s Berlin for you. Nobody minded.

Wolle XDP: For the Love Parade in 1997, I did a party in the S-Bahn arches at Hackescher Markt together with Ralf from Suicide and later Casino. It was called Love Bytes. At some point, the Hateparade came marching along. I had no idea what was coming at us, so the first thing I did was to alert our security. To me, it looked like a protest thrown by people who hated techno. Some kind of punk sound was roaring from the trucks and there were tons of cops. Ralf said to me, “They won’t do anything, it’s just the Bunker kids, and it’s a counter-demonstration to the Love Parade. The Hateparade.”

Mo: That was another world. I don’t know how much the people behind the Love Parade felt provoked by the Hateparade. I didn’t expect a counter-demonstration to cause a rethink of the Love Parade. But as a provocation, it had an important function. That was the idea behind taking part.

Chapter 5: Love vs Hate

As the Hateparade and its criticism of the Love Parade became more well-known, the animosity between the two increased. At the same time, some of the issues addressed by the Hateparade organizers, especially around commercialization, mirrored the creeping alienation from the Love Parade that even parts of the Berlin techno scene reported. While it was still one of the scene’s most important weekends of the year, there was a growing disconnect between the Love Parade, their organizers and the club scene. In that context, the Hateparade’s denunciation of the Love Parade’s business practices fell, at least in some parts, on fertile ground.

Wolle XDP: The Love Parade was already totally done for. For the people in Berlin and the Berlin club scene, the parade was just the weekend where you could finally meet a load of people who you otherwise wouldn’t see, and where you could make really good money as a club. None of the people from the club scene were still going to the parade at that time. The clubs—which were at the core of the scene—and the organizers of the Love Parade moved in parallel universes. At the time, there was hardly anyone DJing at the parade who wasn’t part of that crew based around Low Spirit and Planetcom.

DJ Disko: The Planetcom people immediately found out that the Hateparade was going to happen. At the time, the Love Parade GmbH and Planetcom were like a gang. They were a conspiratorial circle of people. I was a former resident DJ at E-Werk and was the presenter of the Viva House program on the German music TV channel Viva. In 1998 I started as the press spokesperson for the Love Parade. My position was: The best way to deal with the Hateparade is simply to invite them over and talk to them. In my opinion, there were a lot of justified objections from their side.

DJ Fater: The Love Parade sometimes behaved very arrogantly.

Disko: We were the enemy. And that was okay. I endured it with dignity.

Trauma XP: At Radio Fritz there was once a discussion between me and Dr. Motte, that must have been in 1998 or so. Listeners could call the studio and ask questions. Motte didn’t have it easy. The plan was for us to DJ back-to-back, which didn’t work, because all my records seemed twice as fast as his.

Disko: Of course, next to Motte, the attacks were also focused on me as the press spokesperson.

Trauma XP: When Disko came in as the press spokesperson, the Love Parade had already blown it in terms of their communication.

Disko: A lot of things were changing. Jürgen Laarmann was out. Frontpage magazine went bankrupt. E-Werk closed. Motte was totally unhappy. Then a lawyer named Scheuermann came on board, which was new. That was the step that made the whole thing seem much more official and business-oriented. Motte in particular had really big problems with that.

Moog T: I joined the organizational team in 1998. We often spoke with the Love Parade GmbH and also with Motte. The point was always that there was not only one company but several GmbHs and various interest groups behind it.

Trauma XP: The worst thing was just this web of companies, including Low Spirit, Loveparade GmbH, Planetcom and Mayday. They all did business with each other and surely wrote invoices, but in the end it turned out that we all earned nothing, and were actually terribly poor.

Disko: Motte had difficulties with various business ideas that had come from Scheuermann. He even made a fiery appeal to his fellow organizers, but he was reigned in by Sandra Mohlzahn, who had this very quiet manner. She said, “But Motte, what do you want to do otherwise?” Motte had threatened to end the Love Parade, because for him the fundamental idea behind it had been dragged through the mud. That cynically blunt comment by Sandra first caught him off guard and then silenced him. Suddenly it was also about incredible amounts of money. That has to be said.

Moog T: There was also a legal squabble between Trauma and Planetcom, which didn’t make things any easier. He was accused of hacking and abusing their mailing list.

Disko: In 1997 there was indeed a legal dispute between techno.de and the Love Parade, or rather between Planetcom and Martin, because he sent out an announcement for the first Hateparade via the Love Parade mailing list. The dispute wound up in a Frankfurt court. I didn’t know that at the time. However, Ralf Regitz had made it clear to me that the parade wanted nothing to do with the gabbers. The atmosphere was toxic. Internally, there was this attitude that we wanted absolutely nothing to do with them.

Trauma XP: I sent an e-mail to techno.de, which was the mailing list of the Love Parade. The only thing I had to do in order for my email to go to all the recipients of the mailing list was to edit the sender field. Then my mail just rushed through like that. I thought that was very funny, because it went to thousands of people. The Love Parade, however, didn’t find it so funny.

The Love Parade went to the police when they found out. The police had no idea what they were talking about. That was back in 1997, and the police and prosecutors didn’t even know what an e-mail or mailing list was. They then brought up an old law dealing with falsification of technical records. It was a law that was conceived for ATM fraud. But an e-mail is not a technical record. After I received a phone call from the police, I went to a lawyer. He said that changing the sender on an email would roughly be equivalent to changing the sender on a letter. That is not punishable by law. They realized that at some point, then stopped the whole thing. It never went beyond a preliminary investigation and never landed in court. Of course, it didn’t exactly improve my standing with the Love Parade.

Disko: For me it was strange. I had been there from the second parade, and always experienced the whole thing as a confirmation of our ideas. But the bigger it got, of course, the more open to criticism it became. I realize that today, but back then it basically felt like shit.

Mo: At the time, the Love Parade was essentially this internationally shining symbol. The Hateparade was a local thing. From the outset there was never the intention to attract those kinds of masses.

Chapter 6: The Hateparade Becomes The Fuckparade

In an attempt to shake-off the association with violence, which was mostly drawn from Berlin’s yellow press, the Hateparade organizers decided to change their controversial name in its second year. The Fuckparade was born. While at heart still an event for extreme music fans and gabber heads, the Fuckparade also attracted techno fans who had become dissatisfied with the commercialized mass event that the Love Parade had become.

Trauma XP: In the second year we changed the name to Fuckparade. We chose it because the word “fuck” also has something to do with love. It’s also a stereotypical hallmark of many gabber tracks. We also wanted to scare off the candy ravers. That even worked for a while.

Disko: When they changed the name to Fuckparade, it didn’t make much sense to me. I just thought: “Hmm, there’s more fucking going on at our thing.” It was the wrong name. Of course, the press all jumped on the name Hateparade. But you have to endure that.

Wolle XDP: I was running a club called Discount in Mitte. But the district became totally gentrified. I had to close in 1998, and I remember as we were loading the sound system onto a large flatbed truck. It kind of looked like one of the Love Parade’s trucks. Then someone said, “Let’s do a truck for the next Fuckparade.” I briefly paused, and then I thought, “Well, why not?”

Xol-Dog 400: Then Wolle came along. He hitched onto an ongoing project. He brought his audience, which opened up a new audience for us. That can be seen either positively or negatively.

Wolle XDP: The gabbers didn’t necessarily want us around. For many of them, I was just this flashy commercial techno guy. But some people also knew that I had initiated the Bunker and in particular the first Hartcore parties in 1992.

DJ Fater: For a parade like that you also need a few people who have a little bit of talent when it comes to putting together an event. The average gabber was still rather naive in that department. From other scenes, there were people who had already done that kind of thing. They then helped us.

Trauma XP: It was also a question of finance. We needed someone with event experience. In the beginning we did benefit parties to cover the expenses so that we wouldn’t go bankrupt.

Moog T: When Wolle came along, the press kind of pounced on him. He was a well-known Berlin promoter and DJ, and he also had something to say politically.

Wolle XDP: When I made the decision to participate in the Fuckparade, a lot of jaws dropped. “Do you really dare to get together with them?” I knew what would happen if I registered a truck there. The arrogance with which the Berlin scene had treated the Fuckparade to date was over at that point. The moment that someone from their own ranks had defected, it was no longer so easy to ignore their concerns. I expected a lot of backlash from the club scene, and indeed, that was the case. But I didn’t care. I had nothing to lose.

Panacea: I think at the time some people just dared to do it and had become self-confident enough to take a stance. At the end of the ‘90s both gabber and drum and bass were really interesting, so you could position yourself as an unruly outsider.

Xol Dog 400: We saw ourselves as the avant-garde, not the outsiders. We already had a rather elitist stance. We felt like the real and only true representatives of the techno underground. All the rest was a conventional carnival with elevator music.

DJ Fater: We definitely thought of ourselves as superior.

Xol Dog 400: It wasn’t David against Goliath, but us, the elite, against the commercial crowd.

Panacea: It was clear that as a gabber and hardcore DJ, you wouldn’t get a big slice of the techno cake. It was simply too much of a niche genre. Even drum and bass had a relatively short half-life for the hype. That niche also had its own arrogance and attitude.

Wolle XDP: The creators of the Love Parade had moved so far from the actual scene that their power had started to crumble. Those who said anything negative about Jürgen Laarmann, Frontpage, Low Spirit or the Loveparade in the early-‘90s could be sure that those statements would have an impact on their business. If you messed with them, you would be drawing the short straw. I’m a perfect example. Suddenly everything was over and done. Gradually, in 1999, more and more club DJs came to me and wanted to play on my Fuckparade truck. It was like a liberation. And then even Disko changed sides and played with us.

Disko: I think I had only half-jokingly suggested playing at the Fuckparade to Trauma. But then we really went through with it. That was a statement of respect. As part of the opposition, I wouldn’t have done much different than them.

Trauma XP: It was funny that Disko played with us.

Disko: I did have some difficulties with the music. I took my fastest and hardest records, but even that was too soft for them. That was the biggest problem in their eyes, that this commercial moron was playing tralala. Otherwise, I generally felt welcome. I thought that was great. I stood on the truck and felt that we were actually moving in the same direction. No matter what visions we had privately or politically, what brought us out onto the street back then was pretty much compatible. That was the city. We had the same roots. We may not all have had the same dealer, but we had very similar dreams.

Wolle XDP: I don’t even want to imagine what Disko must have heard from Planetcom about that gig.

Disko: That was a huge fuss. I was their press spokesman, and I suddenly dropped out to go and play with the competition. I caught a lot of flack for that which I responded to in the same way that I always do in those situations. I told them to throw me out. They then grudgingly allowed it, and they had to watch while their press spokesperson was photographed on a Fuckparade truck.

Wolle XDP: For a moment I had the feeling that an alternative to the Love Parade was possible—a parade that had not completely sold out its ideals and also clearly positioned itself politically.

Chapter 7: How Big Is Big Enough?

As the Fuckparade gained momentum, the organizers began to face the challenges caused by rapid growth. At the same time, the Love Parade continued to attract more people with each new year. Its success brought with it questions about its status as a political demonstration, and even what it means to have a political demonstration at all.

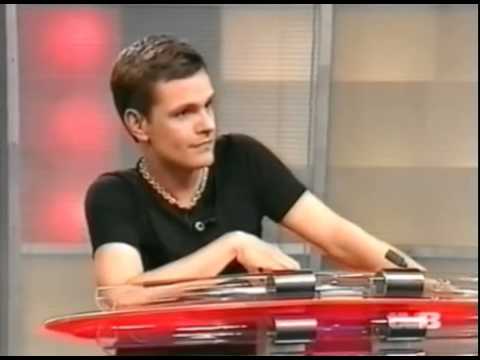

In a legendary talk show interview (embedded above), Disko, the Love Parade’s press spokesperson at the time, joined Trauma XP, Xol Dog 400 and a delegate from the German Green party to discuss the ecologic damage the parade caused to Berlin’s big inner city park Tiergarten and the respective parades’ differing ideas of political protest.

Moog T: The Fuckparade grew and the Love Parade still had more and more people coming to it. The discussions about their status as a political demonstration, about commercialization, about the impact of the Love Parade on the Tiergarten, grew louder.

Disko: The media interest beforehand was total madness. For two weeks I was accompanied by three television crews: an Italian one, one from Singapore and one from Hong Kong. They basically picked me up from home in the morning and never left my side. It was all very exhausting. Suddenly I had to do six video interviews a day, plus countless print interviews about garbage collection and the demonstration status. At some point I thought: I’m going to freak out. It couldn’t be possible, that that is all that was left of the event.

Wolle XDP: The Love Parade was a political demonstration. Because it embodied the absolute opportunism and total conformance with the prevailing system in the techno scene. We bring the youth of the world together just like the state would like to see us: consumer-minded, brand-conscious, politically uninterested, self-optimized, success-oriented and heterosexual.

Disko: It was hedonistic, but not necessarily heteronormative. The press always showed photos of sunflower tits. But there were other pictures of gay guys, sexy punks and so on. Sure the gay subversiveness was more marginalized the larger the parade became. And it was definitely very white. That’s how the scene looked back then.

Xol Dog 400: Those pictures of the ravers who ware dangling from the street lamps looked like a carnival to me. And then the image rights were sold.

Disko: The sale of the image rights barely brought in enough to cover the costs of organizing the parade. That’s why there was this deal, otherwise it would eventually no longer have been affordable.

Wolle XDP: I thought the broadcasting of the parade was dreadful. That wasn’t my world, and it had something staged about it.

Disko: As I said, safety came first. And then, the marketability of the pictures. Of course, the Love Parade had an interest in sending out the right images to the world, which also sold well. There was a political intention behind the selection.

At the debriefing after the ’99 parade, my proposal for 2000 was complete transparency. So many details had suddenly become important. My question to the GmbH at the time was: “Why don’t you just publish your numbers? Show people how much money you actually make.” It wasn’t all that exorbitant. But they saw it differently. I think there would have been a lot of fuss for a week, then the topic would be finished with. Of course, it was about large sums, but it wasn’t nearly as much as the parade brought into the city year after year. What we have achieved for Berlin, just in value added tax alone! In contrast, the revenue was ridiculous. Publishing the numbers would have taken the discussion to another level. I thought the city should stand up for the parade. We also tried to demand that. The GmbH didn’t want to go that way, which was insanely short-sighted.

Trauma XP: The Tiergarten park was looking increasingly battered after the Love Parade and the organizers consistently refused, for example, to install more toilets at their own expense. It didn’t happen—they always insisted that they were a demonstration. That worked for them until 2001. By that time, the city of Berlin had finally figured out that such a commercial event could not be a political demonstration. At least politics was not in the foreground.

Moog T: With the Fuckparade, you could at least recognize the political concerns behind it. Over the years, we have continued to expand on that. In the beginning it was decisively only about the closure of the Bunker. Then in the following years it was about gentrification in general and eviction of illegal and semi-legal clubs and bars.

Xol Dog 400: The number of participants went through the roof around 2000. That happened for us in a flash, similar to the Love Parade.

Wolle XDP: The Fuckparade grew. I was pretty sure that the growth would increase exponentially, similar to the Love Parade in the years before.

Moog T: After the 2000 parade, the signs were suggesting that we could see as many as 20,000 or 25,000 participants in 2001. We began to think about how to curb that.

Xol Dog 400: It had changed completely for me. We were not able to handle the mass of people. There were also people coming who had little to do with our scene and our ideas. I wasn’t happy about that.

Trauma XP: We always had problems with the local assembly authority. The person responsible for that was named Hass, which means “hate” in German, and he did justice to his name. He did not want the Fuckparade in Berlin.

Moog T: There’s a Fuckparade documentary, and in that documentary Hass says something like: “I’m going to erase the Fuckparade from the face of the Earth.” Or something in that direction. He really hated the Fuckparade. We don’t even know why.

Wolle XDP: Parts of the media were very against the Fuckparade. They didn’t want to let go of the image of this dangerous radical left mob, which was established before and after the first Hateparade.

DJ Fater: The police had their water cannons and riot battalions waiting for years. Of course, that didn’t happen at the Love Parade. That also shows what kind of situation they were expecting.

Xol Dog 400: After the 2000 parade, we thought about how to continue. We didn’t want to become like the Love Parade. One idea was that the Fuckparade should end in 2001 with a protest march.

Chapter 8: The Fuckparade Gets Banned

After continuous heated discussions and legal battles, both the Fuckparade and Love Parade lost their status as political demonstrations in 2001. The Love Parade organizers registered the 2001 edition as a commercial street event, and the city of Berlin helped them out financially with the costs for trash removal.

The Fuckparade organizers, on the other hand, decided to sue and simply march the old-fashioned way instead—without sound systems and music—, demonstrating for the people’s right to protest with the means of their choosing.

Trauma XP: The registration for the demonstration always went out in April or May, from us and also from the Love Parade.

Xol Dog 400: Then the letter came with the order of the Berlin assembly authority.

Trauma XP: In 2001, they let us know immediately after registration that they would no longer authorize it. They retracted our demonstration status and banned the demo.

Wolle XDP: I have my own conspiracy theory about that. A demo that big doesn’t get banned that easily. I think the prohibition of the Love Parade was actually meant as the prohibition of the Fuckparade. Politicians had to let the Love Parade die so that the Fuckparade couldn’t develop to its full potential. It was only possible to prohibit the Fuckparade if the apparently unpolitical Love Parade was also sanctioned. Otherwise they couldn’t have done it. The Fuckparade would have become a problem for politicians. It was a visibly leftist—if not radical leftist—demo with extremely high popularity.

Disko: That’s total nonsense. It’s a typical Wolle conspiracy theory.

Wolle XDP: I can’t prove it. But there was absolutely no reason to ban the Love Parade. Why would they risk the most important image-builder and crowd-puller that the city had ever seen?

Trauma XP: The decisive factor for the ban came from the Love Parade, because the assembly authorities concluded that the parade was a commercial event. They then also accused us of that. We immediately objected. It wasn’t that the Love Parade could no longer take place because of us, but that we were banned because of the Love Parade.

Disko: The thumbscrews they used to get us were garbage collection and catering.

Moog T: When our 2001 Fuckparade was banned as a political demonstration, we wrote in our lawsuit that the Love Parade should then also have to prove that it wasn’t just an event, but that it has a political background. But they didn’t succeed. We were able to prove that with our leaflets and political announcements.

Disko: We missed the chance to write slogans on the flags that you can actually nail to the wall. But it had a system behind it. It wasn’t out of embarrassment or because we were too stupid. It was intentional. People took that wrong, quite simply.

Trauma XP: The Love Parade registered a commercial street party in 2001, with everything that goes with it. That meant they had to pay for the garbage and cleaning themselves for the first time. We thought, okay, then we’ll do an old school demonstration without music.

Wolle XDP: The ban on the Fuckparade and the retraction of its demonstration status was a deliberate twisting of the facts. They pretended that there was no difference between us and the Love Parade.

Moog T: After the ban, we considered whether to do a spontaneous demonstration with one vehicle. That is permitted under German law.

Wolle XDP: Some of the co-organizers feared that clashes between the police and protesters could occur if the Fuckparade took place as place as planned with loud music despite the ban. We worried that they’d completely ban us.

DJ Fater: Of course, we thought about just putting a truck there. But we knew that wouldn’t be such a good idea.

Wolle XDP: My approach would have been to say yes and amen, and then still drive through with a fat sound system and not make any speeches, either. The microphone would simply be broken. I was sure that we were right, and I didn’t want to back down so easily.

DJ Fater: That would have escalated.

Moog T: Back then we had pretty good contacts with Radio Fritz, the youth station of the RBB, and pretty soon they said that they would put a broadcasting car in front of the Volksbühne for us and that our DJs could have six hours of Fritz broadcasting time.

Wolle XDP: Then I had an idea that we could use radios to decentralize the music. I had a long conversation with the technical director of the Love Parade about how they managed to get the same music on all the floats. They did it with micro-transmitters. And then I thought that we could do the same with radios on VHF.

Trauma XP: The idea was that all participants would bring a radio. They would turn it on at the Fuckparade, find the right frequency and then that way they would be participating and no longer just consuming.

Wolle XDP: I was totally perplexed. Fritz is a public broadcaster. That means a lot of people at Fritz were willing to risk their job to support the Fuckparade. That was the mood in the city back then.

Moog T: We then wrote that everyone should bring a radio.

Wolle XDP: Fritz had rented the foyer at the Volksbühne and set up the DJ setup there. Originally they wanted to set it up outside. During the parade, the music outside should be quiet, and then after the closing announcement, the sound system should be completely maxed out. That would have been such a great action! Imagine 20,000 people with radios raving in front of the Volksbühne!

Trauma XP: The meeting point was at Frankfurter Tor in Friedrichshain.

Moog T: The demo was supposed to lead from Frankfurter Allee to the Volksbühne. At Frankfurter Allee, the cops were standing there with trucks, announced a radio ban and collected all the radios that people had brought. That was perversion of justice. It was a unilateral move by the assembly authority. We sued them for that. And after two years, we won the case.

DJ Fater: We were forced to give speeches. There was even a mandatory period. We satirized that. Especially Xol Dog 400. He just sampled a speech and played it back. Nowhere in the decision did it say that the speech had to be held live, but then we were sued by the assembly authority. It was pure harassment.

Moog T: After Xol Dog 400, Wolle and Martin had given their speeches at the conclusion of the Fuckparade in front of the Volksbühne, someone turned on a sound system in a VW bus.

DJ Fater: It was this little van with a modest sound system.

Moog T: Immediately, a police brigade started moving forward in turtle formation. They tore out the cables and confiscated the sound system!

DJ Fater: The police shut it down pretty roughly. They went straight into the dancing people.

Wolle XDP: I was overtly against any troublemaking. The media was just waiting for riots to happen.

DJ Fater: Gabber people could definitely dish it out and defend themselves if they felt the need to. They didn’t wear terror hoodies for nothing.

Moog T: When the cops had finished, they realized that they were encircled. Then Trauma, Wolle and I were between the fronts. On one side they stood with bottles, on the other with Tonfas. It was really on the edge. Luckily it didn’t escalate any further. On the roof of the Volksbühne there were still a few people from the Köpi [a formerly occupied autonomous housing project and cultural center on Köpenicker Straße in Berlin’s Mitte district], who showed their bare asses, which led to some amusement.

Chapter 9: The Fuckparade After The Ban

Following the ban, the Fuckparade organizers regrouped to discuss how to continue. By then, the Love Parade had officially become a commercial street event, which mooted the Fuck Parade’s main point of criticism. Despite this, the lawsuit against the 2001 ban was still underway, and it became clear to Trauma XP and Moog T that they needed to continue at least until there was a final verdict.

After some changes in the organizational team, the Fuckparade shifted its entire focus to political issues, ranging from violent repression of illegal parties and subcultural activities to gentrification and new surveillance laws. When the Love Parade held its last event in Berlin, in 2006, the Fuckparade had already emancipated itself from the intense rivalry of the first years.

Wolle XDP: After the radio ban, the others had somehow run out of steam. They delivered the speeches at the maximum volume. I didn’t want that, so I dropped out.

DJ Fater: Eventually, the political aspect was almost more important to me than the music. The party stepped into the background for me. That’s why I was also in favor of doing a “silent” Fuckparade without any music. That way, it was not the party people who would come, but the people who have a political claim.

Moog T: In terms of volume, we complied with the strict requirements of the assembly authority. That was one reason Wolle did not agree.

Wolle XDP: The assembly authority had restricted us so much that you could no longer distinguish the Fuckparade from any other rally. I didn’t want anything to do with it.

Moog T: Wolle said very clearly that he would not be there under the new terms. I thought it was important for the Fuckparade to carry on. If you want to establish a demonstration with serious political aspirations, then you simply have to follow some rules. Of course, you can occupy a house, publish a press release and then be evicted by the police under the use of force, and then issue a press release again. But we wanted to create continuity.

Trauma XP: 2001 was actually intended to have been the last Fuckparade. The ban and our declaratory legal action made everything different. We wanted to demonstrate in court that we had been wronged in 2001, and that this could be repeated at any time. It was then determined in the context of this complaint that the radio ban was not lawful and that the Berlin assembly authority had perverted the course of justice. That went pretty fast.

Moog T: Wolle and Xol Dog dropped out and Trauma retreated even further. I then made a cut and decided that only six trucks would be allowed to run. I suggested to the organizational team that we shouldn’t have more than 5000 people.

DJ Fater: There was always an idea to stop, but for some reason we just kept going. One reason was the legal challenge. As long as that was active, there should also be a Fuckparade.

Disko: I still followed what happened to the Love Parade after I quit in 2000. It went in the wrong direction. And the opportunity was continually lost to take a position or to reestablish anything. That was really a pity. And after they managed to start a debate, the Fuckparade wasn’t capable of any further ideas. They just went in circles around themselves.

Moog T: At some point we in the left-wing scene were criticized for not clearly delineating ourselves from the right.

Disko: Suddenly they were faced with the problem of having to shield themselves from unpleasant guests.

DJ Fater: There was a campaign with the motto: “cool kids don’t dance with gabba nazis”. That was in 2006. The Fuckparade was accused of being a sham, an “unpolitical subculture” that tolerates right-wing content. But we have always positioned ourselves clearly.

Panacea: I think that’s stupid. If you really are inclusive, you also have to let the hooligans and wankers go along with you. But they have to behave.

Moog T: Fascists or people with Thor Steinar clothes don’t come because of the demonstration, but because of the party. We said that if you see fascists, go to them. Talk to them or punch them in the mouth. There are 8,000 people, we didn’t personally invite all of them. Everyone who registered a vehicle also had to write a text explaining their political intentions, which was then put together with all the other texts into a big announcement text. You can’t do any more than that.

Trauma XP: Years of litigation followed. We also filed a continuation claim. Our goal was to show that in order to achieve media attention, you need to be creative and use up-to-date resources. Like music, for example. That then dragged on for a long time until it had passed through the individual legal instances.

Moog T: Through these dogged negotiations in the courts, the Fuckparade opened the doors for political demonstrations where the focus is on music, and there are plenty of them in Berlin now.

Wolle XDP: When the time came, however, the spirit of optimism which existed around the Fuckparade in 2000 and 2001 completely vanished.

Chapter 10: It’s Political After All

In 2007, the Fuckparade organizers finally won the legal battle that started back in 2001. Even better, Germany’s Federal Administrative Court decided that the parade met the definition of a political demonstration. This landmark ruling changed Germany’s political protest landscape, a change that’s had an impact until today. During this time, the rights to the Love Parade were sold-off to Rainer Schaller, owner of fitness center chain McFit, who relocated the Love Parade to the Rhine-Ruhr area, where a tragic event caused it to shutter for good.

In the years since, the Fuckparade has established itself as an annual event that addresses various left and radical-left leaning political topics. Musically, gabber and hardcore have become less dominant. In many ways it’s more popular than ever, with attendance fluctuating between 5000 and 10,000 per parade.

Trauma XP: In 2007, six years later, the Federal Administrative Court made its decision and declared that we were right. That’s one reason why I registered the Fuckparade for ten years. As long as the lawsuit went on, I had to be the applicant. In 2003, I became a father and my priorities shifted slightly. Nevertheless, every year I had to go to Berlin to register the demonstration and to meet with the police because we still had this lawsuit going.

Moog T: Ever since Trauma withdrew completely, I have been accompanying the Fuckparade as a kind of consultant. Someone has to speak the same language as the police. And as the participating groups have shifted more and more into the radical left corner in recent years, cooperative talks with the police have become somewhat more difficult. That’s why I’m sitting there. The assembly authority and the police already know me. They know that if I’m running the demonstration or if I’m the contact person, then the demonstration will happen without mishaps..

Disko: When the Love Parade stopped, the relevance of the Fuckparade was no longer there. De facto, the Fuckparade only exists because of the success of the Love Parade. It developed on the shoulders of the Love Parade. And that was fine. No one is interested that it still exists today.

Xol Dog 400: Neither the Love Parade nor the Fuckparade really achieved anything in my opinion, neither politically nor culturally.

Moog T: The Fuckparade has established itself as an annual event and demonstration.

Trauma XP: Moog manages it to this day. He’s also a mad scientist, so I trust him to have created a sustainable and independent structure there.

Moog T: To this day, the Fuckparade is not externally financed. The principle remains: no sponsors and no advertisements. The money we need for GEMA and other things is collected through benefit parties. The funds flow to the account of the Fuckparade. And if we see an alternative project in Berlin that needs money, then we support them.

DJ Fater: When the Love Parade was no longer held in Berlin, a lot of people came to us who otherwise would have gone there. I didn’t want to deal with them. They had no idea why the Fuckparade exists and what our political stance is.

Moog T: The number of participants varies from year to year. After the parade in 2010 had grown back to over 10,000, we again made a cut. We also tried to filter the audience somewhat. Because a lot of trucks had joined from the surrounding rural Brandenburg areas and were playing this ultra-fast crystal meth schranz techno, there were suddenly a lot of people that didn’t fit the crowd. There was no visible sign of any political background. In the last few years, there were virtually no gabber trucks anymore. Instead, it was mostly crews from left-wing circles and free tekno sound systems.

Trauma XP: The judgments of the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Administrative Court are still relevant now. It’s only because of these judgments that demonstrations can take place today with mobile sound systems. The assembly authorities try again and again to shoot it down, but they haven’t gotten away with it yet.

Moog T: After the success of our lawsuit before the Federal Administrative Court, it finally has become legally clear that music can indeed be an expression of political opinion. It doesn’t matter if it’s the DGB choir or hardcore gabber. The Fuckparade was the seed for a new demonstration culture in Germany, which remains valid to this day.

Published April 29, 2019. Words by Sven von Thülen, photos by Marco Microbi.