Interview: Hans Ulrich Obrist speaks to Milan Grygar

Milan Grygar is one of the world’s first sound artists. Born in the Slovakian town of Zvolen in 1926, he first began exploring alternative forms of musical notation and recording the sounds of his sketches in the late 1950s. These acoustic drawings eventually caught the attention of other notable sonic-experimentalists, including John Cage, with whom Grygar had been planning collaborative performances shortly before Cage’s death in 1992. Hans Ulrich Obrist sat down with the artist to find out more about the lineage of the Eastern European avant-garde.

HUO: Who were your artistic heroes growing up? Were they Czech or international?

MG: Before I started studying at the College of Applied Arts in Prague, I didn’t know very much about art at all. That changed pretty quickly when I met the architect František Kalivoda, who was my teacher and who had been a friend and collaborator of László Moholy-Nagy. In 1935, Kalivoda had organized a large exhibition of Moholy-Nagy and put together a magazine called Telehor, of which the only issue that was ever published had been entirely devoted to Moholy-Nagy’s work. That was eye opening for me to say the least.

I always found Moholy-Nagy’s Gesamtkunstwerk approach one of the most interesting aspects of his art—his bridges between architecture and visual art, as well as his utopian dimension. What fascinated you about Moholy-Nagy?

It all seemed somehow familiar to me, because I had seen Moholy-Nagy’s work as a child in a magazine called Žijeme that was put out by the graphic designer Ladislav Sutnar that my father always bought. But I didn’t have very much time to explore art during my studies because they were interrupted by the war. I ended up pretty quickly as a forced laborer in an arms factory in Brno in the forties, so I finished my studies after the war.

So what do you consider to be your first work as an artist? Where does your catalogue raisonné begin?

[laughing] I would never put together a catalogue raisonné.

But can you tell me a bit about your early exhibitions in the late fifties?

These were mostly paintings, some geometrical, some still lifes.

In Prague at the time, there was still a historical proximity to the Russian avant-garde of the teens and twenties. I’d be very curious to find out your relationship as a young artist to that era.

The Russian avant-garde is something I have always been fond of. In fact, our information about international art was not quite so limited after all.

When did your visionary work with sound begin? Did you have anything like a sonic “epiphany”?

One of the most important moments was seeing American artists at the Biennale in Venice 1964, especially Robert Rauschenberg. This really gave me the confidence to think about creating art in a freer fashion. Of course, Italian futurist Luigi Russolo was also extremely important for me.

When did these influences first begin to play a role in your work?

That was in 1965 with my acoustic drawings, when I recorded the sounds of what I was creating visually.

Your acoustic drawings look like a form of musical notation.

You see, my father worked for a railway company and I grew up in and around various train stations. I always had a certain sensibility to the sounds I was surrounded by. Pretty soon it branched out to all of the various objects I had been drawing with. That’s when I realized that every drawing I see I can also hear, and so I chose to exhibit the recordings of the sounds of the drawings I made. That was also 1965. Everything I make visually, I also record.

But how did you end up “inventing” them? You would consider this an invention, no?

Well, it was a process and it took around a year and a half. It mostly involved thinking about the bodily rhythm contained in drawings—that is, contained in their execution. It was part of a longer process, not an epiphany.

Does that also go for the visual presentation as a kind of notation?

Yes, developing that was also a process, not a single moment. Erhard Karkoschka actually published the first book on alternative notation, even before Cage. Eventually this led to Karkoschka having my scores performed internationally.

John Cage also had the idea of the “open notation”. Was that ever of interest to you?

I did work with open notation and incorporating moments of chance in my compositions. So yes, there was that similarity. But for me, these were certainly controlled moments of chance. Before Cage, I had been interested in Schoenberg’s writings. When I first started my sound drawings, I knew nothing of Cage. Only after Karkoschka had published my work was there a real connection. Eventually I met Cage the year he died in Bratislava. We were preparing a joint exhibition in Prague but before it was finished he passed away. It was actually supposed to be a concert: Cage and Grygar. There was an exhibition and concert that took place in 1993-94, but unfortunately without him.

There’s also the connection to birds in your work, which conjures up the compositions of Olivier Messiaen. Can you tell me about that?

Birds actually never really interested me—rather only the bird-shaped toys that made bird sounds. I started experimenting with these toys around 1966. I had been drawing mostly by hand with a pen until a certain point when I started branching out, and eventually drawing with the toy birds. I was particularly drawn to the sound the beak made, which I dipped in ink, drew with and recorded.

Tell me about the role of collage in your work. It’s very different to the surrealistic approach of, say, Jan Švankmajer, who I’ve also visited while being here in the Czech Republic.

My work is anti-surrealistic. But to answer your original question: collage was never really so important for me.

At a certain point, you began incorporating the conventional lines of staff into your notation. How did that come about?

You can see it as a kind of visual “horizon”. Shortly before Cage died he gave a talk in Bratislava. Someone in the audience asked him what connected the visual arts with music and he replied, “The horizon.” I had actually begun including staffs in my drawings before Cage had said that, so it was a kind of validation of my approach. For me, the staff functions as a spatial element.

And how did that turn into collage?

It was a natural progression. For example, I would take a drawing of mine, cut it into pieces and then rearrange them in a totally chance fashion. I recorded the entire process—that’s what the accompanying record is.

So the recordings of some of your larger works are almost like soundtracks to your art. Films have soundtracks—is this comparable?

Absolutely.

Some of your works look like palimpsests, with their overlapping visual information.

Well, the drawings are really functional. What you’re seeing often are operating guidelines for constructing and manipulating the objects pictured.

Do the numbers in your work have a specific function?

They usually denote the order in which the guidelines should be followed.

Was the idea to partially remove the art from the object—to have it function independently of or beyond the object shown?

Well, the emphasis is more on the action in relation to the object.

With musical notation, you’re dealing with something that musicians are able to play over and over again. It seems to me that art in the twentieth century had been very focused on objects. I’m not sure if you know Marcel Duchamp’s Unhappy Readymade, or Moholy-Nagy’s works with telephones, both of which had a focus of transcending the object.

Creating art “beyond” the object was not really my interest. You know, I had been planning an exhibition of sounds, like today’s exhibitions with prerecorded sounds being played in a certain space . . . Honestly, my work happened very gradually.

I was good friends with Iannis Xenakis and he had the idea of polytopes—sound spaces in which you can completely immerse yourself.

[laughing] Well, I work with the limited spatial understanding of an artist. Xenakis had a far more sophisticated and perfect understanding of space.

That’s a very modest way to put it. Personally, I find your conceptualizations of space impressive. What’s also of interest to me are your tactile drawings and performances involving the penetration of the canvas or paper—breaking through the two-dimensionality of the image. To me, they’re reminiscent of Gustav Metzger and Lucio Fontana—but you also recorded them as well. You must have an enormous sound archive.

Yes, I have audio recordings of almost everything I’ve ever done.

There’s a work by Rainer Maria Rilke entitled Letters to a Young Poet where he offers advice to an aspiring young artist. What would be Milan Grygar’s advice?

I don’t like giving advice. ~

—

Photos:

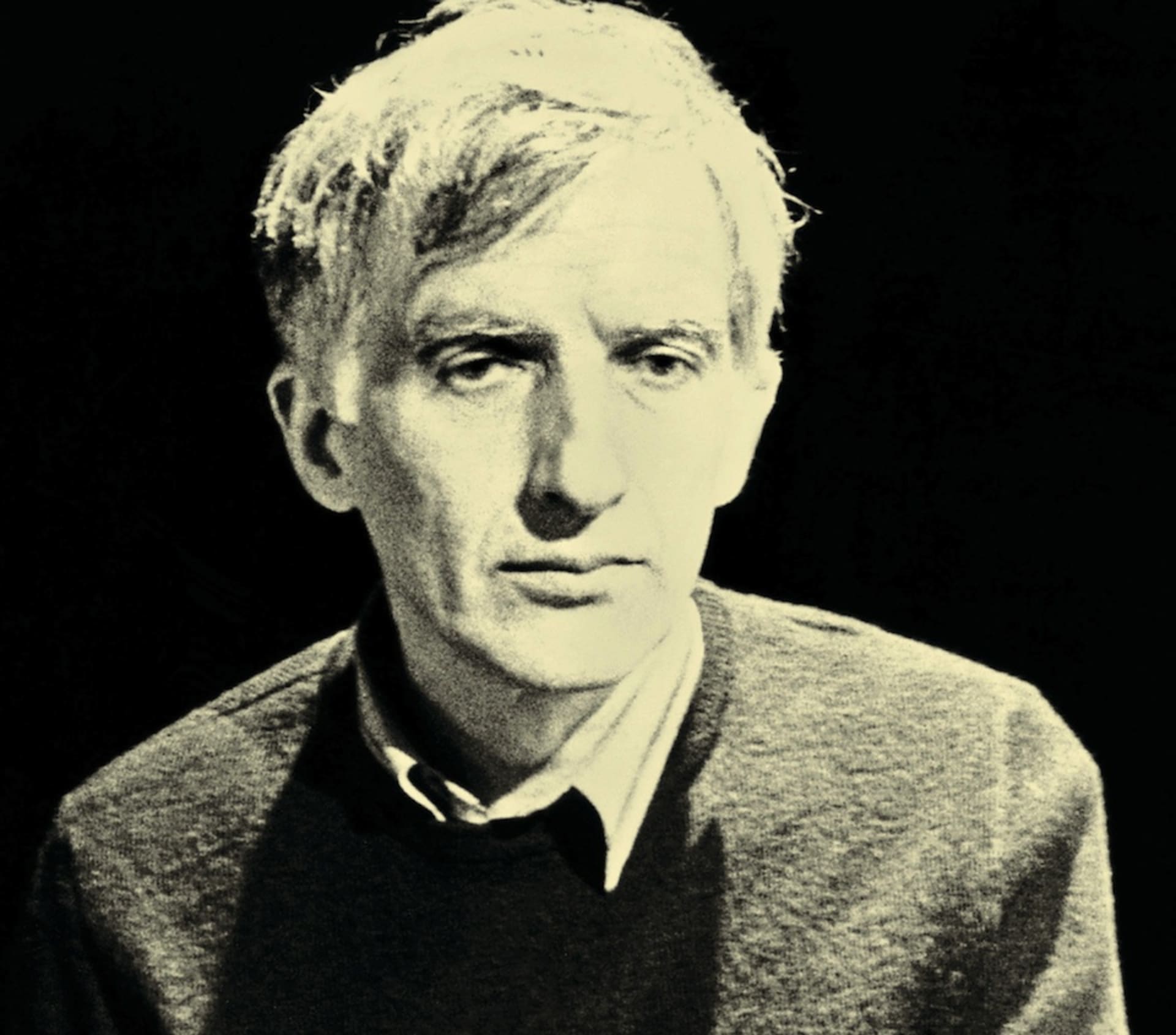

1. A portrait of Milan Grygar from the artist’s archives.

2. Milan Grygar, Tactile Drawing, Recording of Realisation, performance, 1969. Photo: Josef Proek, courtesy of Milan Grygar/Galerie Zdenek Sklenár

Published September 08, 2012.