How Authentic Is Pop-Feminism?

Beyoncé, pop cultural feminism, and the dilemma between progress and exploitation.

Brands and branding increasingly determine our everyday behavior. They create a sense of belonging, identification, and trust. Beyoncé’s is such a brand. In the past, the pop star has used this status to make clear political statements—and has repeatedly received criticism for it. Is feminism ultimately just a product that artists make use of strategically? Or is there more to it?

In this excerpt from “Brand Identity Feminism or Feminism as a Brand Identity?,” a full-length essay featured in the Electronic Beats book (created to celebrate 20 years of Electronic Beats), cultural critic Aida Baghernejad explores how throughout the past, pop stars have incorporated feminism into their personal brands and whether Beyoncé’s “pop feminism” can be viewed as authentic. Order the book now to read the full piece.

Brands are a dominant force in the contemporary world. No longer just logos on consumer goods, they are complex constructions with sometimes more, sometimes less fixed identities, value systems, and religious communities. The last thirty years have seen the adoption of branding as a practice from a growing variety of organizations and institutions—from sports clubs to political parties, from NGOs to cities, parks, residential complexes, and every individual. And with the rise of influencing as a viable career option at the beginning of the 21st century, anyone with a social media account–particularly Instagram or TikTok—will recognize the technology’s tendency to reward users with a solid “personal brand.” However, the rise of branding doesn’t always equate to exploitative practices or have negative implications.

Anyone with a social media account will recognize the technology's tendency to reward users with a solid personal brand.

Brands can also act as signposts in an increasingly complex, overwhelming world where traditional gatekeepers have lost their power, and increasing individualization dissolves securities in communal societies. Or, as Goldsmiths lecturer Liz Moor writes in her 2007 work The Rise of Brands, “the logos, symbols, and imagery produced by these techniques have […] become an important resource for individuals in fashioning a sense of place and self within a complex global system.”

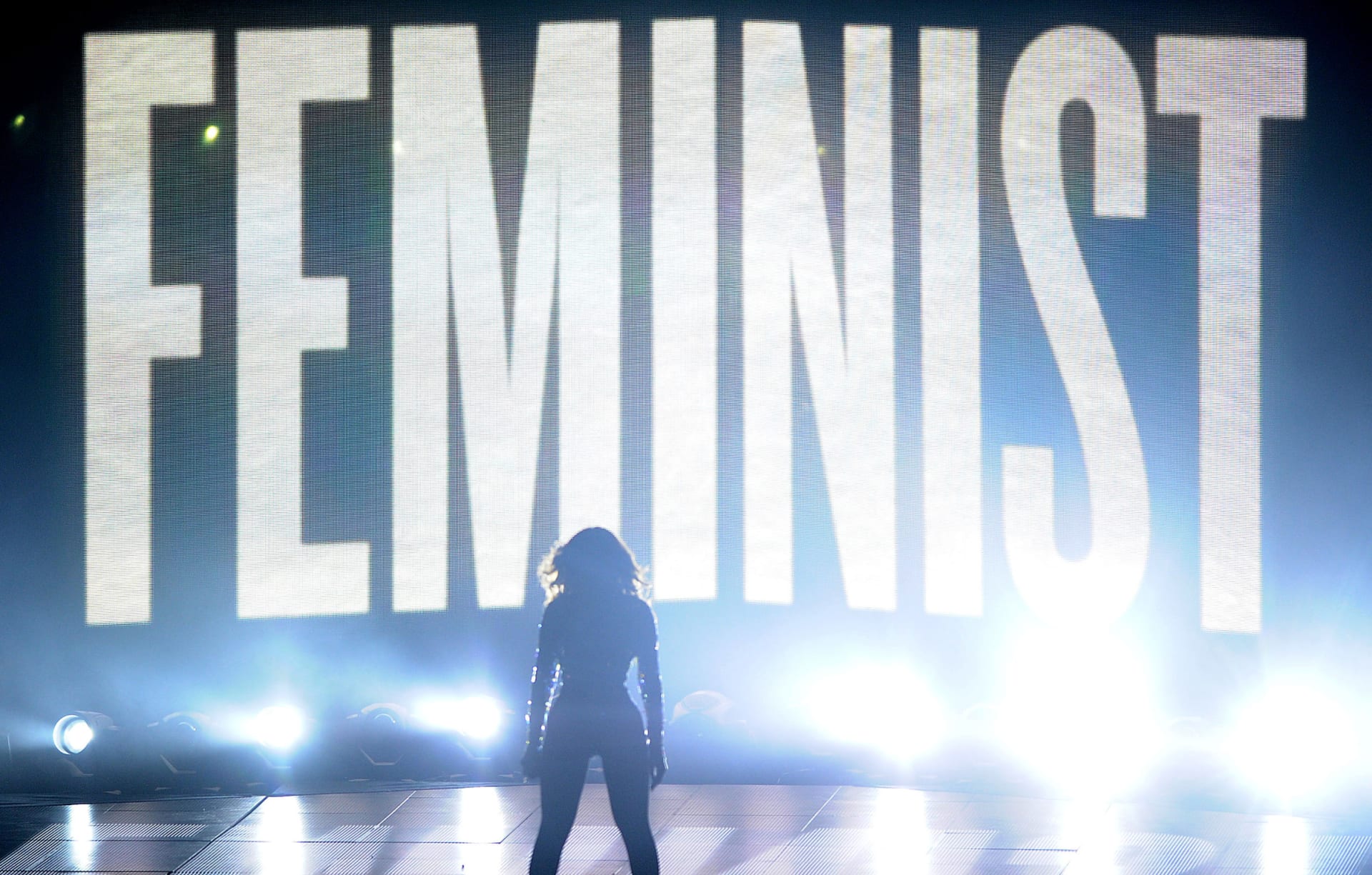

Take Beyonce’s self-titled 2013 album and its notorious sampling of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “We Should All Be Feminists” speech on lead single “***Flawless.” The American pop star’s world tour and performance at the 2014 Video Music Awards featured a giant screen emblazoned with the word “FEMINIST,” as if to symbolize feminism as a brand itself. While Beyoncé’s critics focus on the central and essential aspects of her performance from the viewpoint of a feminist critique of capitalism, one must not forget that an influential pop artist like Beyoncé sees feminism as part of her value system. Appropriating it as part of her brand gives the term a boost in social classes that were otherwise indifferent or hostile to it.

This element will show content from various video platforms.

If you load this Content, you accept cookies from external Media.

Let’s not kid ourselves: Feminism has always been subject to constant criticism, from the early suffragettes to doxxing and other violent practices that feminists are exposed to in the digital age. The phenomenon of “post-feminism,” particularly of the late 20th century and the early noughties was particularly treacherous. It suggested that equality and freedom of choice had long been achieved and were “common sense,” and thus (more radical) feminism would be obsolete.

In the nineties, the confrontational feminism of a group like Bikini Kill was far from the mainstream. Instead, the much more apolitical “girl power” of Spice Girls and German pop star Jasmin Wagner (AKA Blümchen) dominated the cultural zeitgeist. Their narrative declared to be at the end of a fight that had, in reality, only just begun.

Still, a conservative backlash followed in the US with a return to “traditional” values, symbolized by pop artists like Britney Spears, whose innocence and virginity were heavily promoted by her management.

This element will show content from various video platforms.

If you load this Content, you accept cookies from external Media.

In the following years, a neoliberal type of feminism emerged in the form of Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg and her infamous book Lean In. Published in 2013, it dodged addressing structural problems and shifted responsibility to the individual affected by discrimination. The colorful “girl power” narrative in miniskirts and the “serious business costumes” of the Lean In-generation were closer in spirit than you might think. Both images sell one of the core elements of feminism that supports the status quo instead of calling it into question. They’re symbols of consumable and commercialized versions of feminist thought that can be exploited as a product of pop culture.

Crucially, this type of corporate feminism negated the aspect of intersectionality, a concept coined by American lawyer and theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw which focuses on the interaction of different forms of discrimination—for example, discrimination based on race or class—which take on another dimension through they are interlaced. Intersectionality represents a form of multiple marginalizations which coincide with the person affected. But if you include these and other dimensions in the debate, it inevitably becomes more complex—and complexity is, as is so often the case, the enemy of exploitation.

Complexity is, as is so often the case, the enemy of exploitation.

Think of the example of the inventor of rock and roll, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a queer Black woman who came from a poor background in the southern United States. As one of the first artists to use distorted guitars, she shaped the foundational sound of pop. Even Chuck Berry, a member of the genre’s vanguard himself, admitted that his entire body of work emulated this pioneer. And yet her name disappears behind Little Richard and Chuck Berry, just as Elvis overshadowed the latter.

Other examples are artists like Nicki Minaj or, more recently, Cardi B. Her collaboration with Megan Thee Stallion, the track “WAP,” published on August 7th, 2020, was harshly criticized by columnists and critics citing the explicit nature of the song. These same critics of course ignored the fact that male colleagues have been singing and rapping about sex since the very beginning of pop culture without anyone beating an eyelash. The backlash seems to be reserved only for women like Cardi B, and any criticisms directed at them are even harsher when they are not white women.

Look beyond the mainstream, and you’ll see that it is no different in the electronic music scene, which sees itself as progressive. While women and non-binary people are made invisible or are discriminated against, women of color and people with multiple factors of marginalization are often the targets of sheer hatred and projections, particularly online. For example, artist object blue, a queer woman of color who was recently featured in our Life Forces web series, has had experienced several incidents of harassment from trolls and negative comments in live stream appearances on other platforms.

This element will show content from various video platforms.

If you load this Content, you accept cookies from external Media.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that commercialized feminism and “post-feminism” refer primarily to the so-called “Western world” and its pop-cultural space, as media and cultural studies professor Simidele Dosekun explained in an article published in 2015 titled “For Western girls only? Postfeminism as transnational culture.” In the story of “girl power,” she writes, women in the global South appear at most as “girls to be empowered,” as people without agency and, to put it more cynically, merely as recipients of neocolonial aid programs.

If an artist like Beyoncé appropriates the self-description as a feminist, it’s always part of a brand repositioning—regardless of whether it is strategic or not. Coming from a Black woman who, in her definition of feminism, refers to another Black woman, Adichie, this adoption of feminism as a brand is nevertheless a radical act within the capitalist pop-cultural space which Beyoncé inhabits. It stands out from the individualizing and apolitical “girl power” and Lean In narratives, because for a marginalized minority—especially the Black community in the US, and especially the women in this community—survival in itself is a political act, let alone to be successful in a world that perpetuates structural discrimination of Black women and misogynoir.

Aida Baghernejad is a writer, cultural critic, and Ph.D. candidate based in Berlin. You can read her full-length essay “Brand Identity Feminism or Feminism as a Brand Identity?,” published in German, in the Electronic Beats book.

Published March 24, 2021. Words by Aida Baghernejad, photos by Jason LaVeris/FilmMagic.

Follow @ElectronicBeats