How Berlin’s DIY Club Culture Inspired The New Singapore Rave Scene

It’s not often that you get to witness a new club scene bubbling up from the underground, filling previously untrodden spaces with fresh sounds and eagerly dancing bodies. But when you do, the energy is electric. During a recent trip to Singapore, I found myself repeatedly presented with indications that nightlife was no longer the VIP-and-bottle-service monoculture that I had grown up with there as a teenager in the mid-2000s.

[Read more: Discover Seoul’s rapidly growing underground dance music scene]

A tiny island at the tip of the Southeast Asian archipelago, Singapore is known for its strict laws and sparkling clean, orderly streets. In the ’90s, the country had a small underground electronic music community, particularly in the drum and bass scene. But a luxury boom spurred by rapid economic growth fueled a thriving VIP nightlife culture in the 2000s. Storied clubs like Ministry of Sound and Zouk dominated the nightlife landscape, which perhaps peaked in 2011 with Pangaea, the highest-grossing club in the world that year. It was a need for nightlife alternatives beyond velvet booths stacked with bottles of champagne that caused the growth of a new current of underground parties to emerge in their wake. The nascent scene’s greatest challenge, however, has not been to incite a surge in new alternative-leaning parties, but to establish its own identity in an era where western nightlife standards rule supreme.

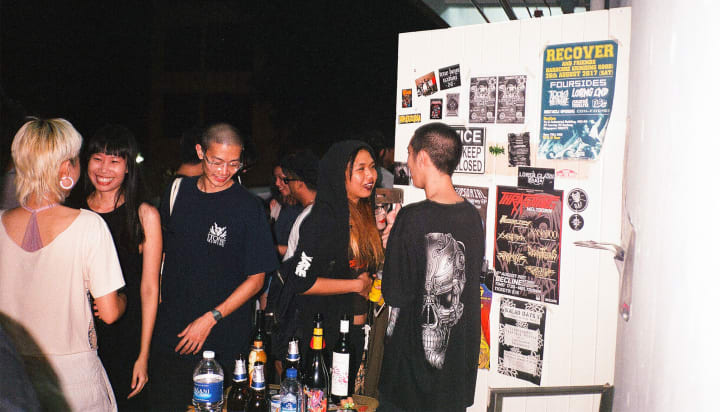

One of the first local industries to grow in Singapore since this shift away from the mainstream club experience has been a boom in a myriad of labels and parties run for and by homegrown electronic music artists. One night in December, I attended a club night hosted by two Singaporean imprints, Darker Than Wax and Syndicate. An array of talented DJs played, but the standout performance was a live set from a duo called NADA, where the singer, face eerily coated in white powder, sang raunchy covers of Malaysian folk songs set to techno, house and disco. Later, Darker Than Wax co-founder Dean Chew surveyed the young crowd of mostly local Singaporeans in their 20s. “The wave is back,” he said with a smile.

The DIY music scene in Singapore ebbs and flows, Chew explained, but about four years ago, he started noticing “more curiosity and hunger for good music again—people are actively seeking it out.” With new independent music collectives springing up, like Ice Cream Sundays, Play by Ear and Kampung Boogie, the scene’s growth has become especially palpable in the last two years.

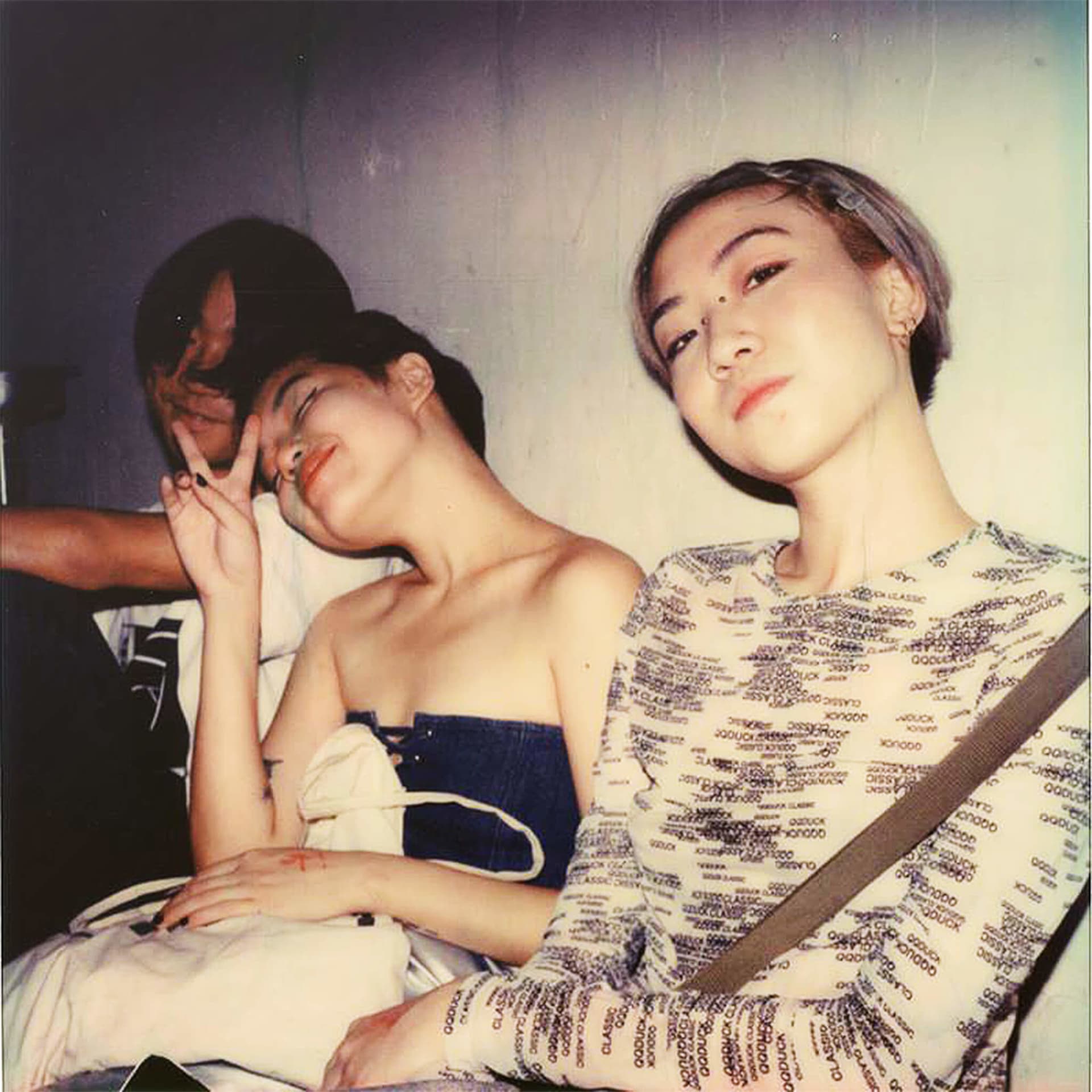

Later that night, I moved on to a mysterious new party called Horizon99, the mere existence of which only confirmed Chew’s observations about the scene’s sudden explosion. Abrasive techno played by local DJs clawed against the walls of a dark room in an otherwise deserted compound; it was the first proper rave many of my friends had ever been to, or heard of, in Singapore. The party’s co-founders, who were in their early 20s, told me that they used to haul a boombox into the Singaporean jungle with their friends before deciding to throw this party. Feverishly dancing next to an industrial fan, I wondered why raves like this didn’t seem to exist in Singapore ten years ago, when I often found myself dejectedly sipping watery cocktails at yet another sterile mega club. Where did it come from, and what was it responding to?

As the current clubbing capital of the world, Berlin nightlife influences what rave scenes everywhere look, sound and feel like. I was especially curious how, in the age of “peak Berghain”—where Berlin club culture has been flattened by endless memes and think pieces into a narrowly-defined aesthetic—nascent electronic music communities in non-Western countries like Singapore look to Berlin for inspiration, while defining themselves on their own terms.

“A scene can never develop in a vacuum,” Horizon99’s co-founders Sant Ruengjaruwatana and Chantal Tan, who DJ as ROT FRONT and A(;D), said via email. They cited the internet as the main arbiter for the spread of culture, and said that one of the reasons why they started their party was to be able to dance to music they could normally only hear on SoundCloud.

“We cannot deny Berlin’s influence on Horizon99,” they added. “However, the Berlin club scene that has inspired us does not lie within the big, predominantly techno clubs like Berghain, Tresor and Kit Kat.” Instead, they cited Creamcake, Herrensauna, Trade and Janus, which they see as “smaller, younger, queerer and honestly, more interesting” events, as well as music made by relatively unknown and underrepresented producers who do not “irrationally idolize Berlin’s traditional (and conservative?) club sound.”

The commodification of Berlin’s club culture has resulted in a rise in techno tourism to the city. “Having been to Berlin, more and more party-goers [in Singapore] are demanding techno and house whenever they go out,” noted Ruengjaruwatana and Tan. They said that as a result, a myriad of local promoters are now throwing weekly techno events that claim to bring the “Berlin” look and sound simply by importing resident DJs from Berghain or Tresor. “This particular strategy seems to be overly stifling, with a very limited scope for interpretation and the natural process of growth and evolution,” they said.

Mark Wong, the founder of Singapore’s Ujikaji Records, echoed similar apprehensions about the Berlin ideal. “Berghain’s success makes it a convenient reference point for others,” he said, “but it’s also easy to think that there is only one way—or one ‘best’ way—of organizing shows, which is nonsense, of course.” Wong’s long-running experimental label throws noise shows in cafes. He also recently began hosting a club night.

Everyone I spoke to agreed that Berlin and Singapore’s rave scenes face vastly different socio-cultural conditions. “We do not have the drugs, we do not have that large a crowd, we do not have that space,” Ruengjaruwatana and Tan put it. The key question is how can we critically analyze the structural conditions [of Berlin nightlife], and break them down into tools that can be re-contextualized to achieve different strategic goals.”

Eileen Chan, who co-founded Singapore’s only techno-focused club, Headquarters by the Council (or simply, “HQ”), was quick to disavow any real influence from Berlin. “What is Berlin club culture? People dressed in all black and no photography allowed in the clubs?” she asked, tongue planted firmly in cheek. “Every community should develop and define their own club culture. We shouldn’t strive to be like any one other city, because we are met with different sets of challenges.” Chan opened her own club in response to this need for a unique local music outlet. “HQ was born out of frustration with the bottle service culture that was slowly overtaking the nightlife scene here. If anything, the only thing from Berlin club culture that influenced us is how the focus is on the music, versus how many bottles of Dom Perignon you can open in a night.”

In a similar vein, Ruengjaruwatana and Tan said they hoped to use Horizon99 to address “the universal problem of precariousness and inequality in the neoliberal reality centered around work,” an issue that is “especially pronounced and relevant within the hyper-capitalist state of Singapore.” Bottle service culture, they said, is a toxic environment where inequality is not just tolerated, but supported.

In this regard, Berlin’s club culture provides a useful model of nightlife unchained from bottle service. “The entire DIY culture in Berlin’s club scape has definitely inspired us to a certain degree,” said Darker Than Wax’s Chew. “I like that it’s raw, it’s not bound by any particular system or preconceived ideas, so it’s more likely to be spontaneous.”

For Ruengjaruwatana and Tan, one of Berlin’s biggest lessons is that “it does not require much to do a party yourself,” and that in fact, “luxury-pandering equipment” like air-conditioning and expensive sound systems can hinder the party from reaching its full potential. Harsh, austere, uncomfortable conditions and sounds at some parties in Berlin have shown them the value of discomfort as a tool that can “unlock and free one from the torpor of the frictionless, normal and easy.” To them, “to party is to feel your body in full once more.”

“Berghain-style might be the one under scrutiny now,” they concluded, “but it is inevitable that we will also be discussing the problems surrounding the NAAFI-style, Staycore-style, Bala Club-style, GHE20G0TH1K-style, Discwoman-style parties soon.” They wondered if this this issue could be avoided—if there really is any strategy out there that could prevent one hegemony to replace another. “Perhaps the only way out is to have a full system overhaul.”

See more photos by Christopher Sim.

Published April 04, 2018.