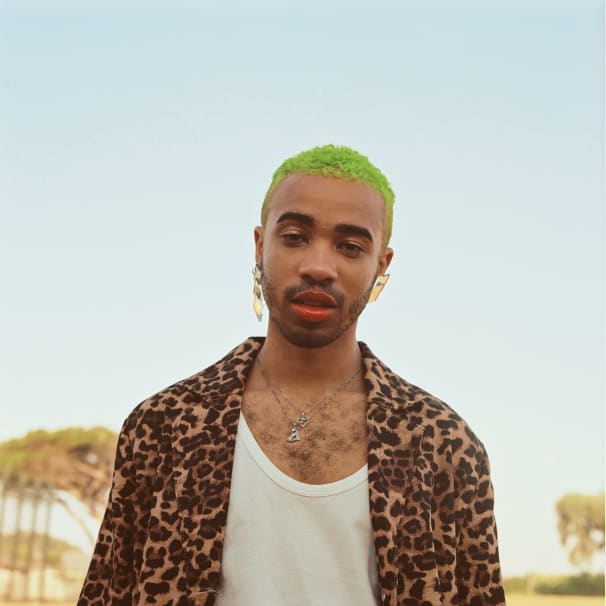

Meet River Moon, South Africa’s Loveable Agent of Chaos

Cape Town's self proclaimed queer “Rave Princess” and meme mastermind discusses “spiral music” and the comedy of confrontation, on and offline.

Cape Town-based DJ, producer and social media maverick River Moon (who goes by they/them pronouns) has taken on a distinct creative mission during the pandemic: to spread joy in the form of dance and laughter. “We really need both in these times,” Moon said over a phone interview—which was, indeed, filled with plenty of cackling.

Their first two releases of the year, “The Rave Princess,” to be released this Valentine’s Day, and “Sick Bitches,” a collaboration with fellow Black and queer techno pioneer LSDXOXO, to be released later this Spring, strives to illicit a demure giggle and simultaneous hip sway in listeners. It’s hard not to smile when singing along to the sassy lyrics of “The Rave Princess,” which proclaims Moon’s reign over nightlife with unapologetic confidence. The dark, sexy track is an ode to memories of glamorous entrances into clubnights past, and Moon’s way of offering listeners a sliver of that cinematic sparkle and safety that queer, underground spaces once provided.

After spending their childhood and teenage years in New York, Moon returned home to South Africa—where they were born and where their extended family still resides—four years ago. “When I got here, I wasn’t alone,” Moon says. “I immediately felt community.” The aspiring DJ and self-proclaimed “rave princess” joined a legion of LGBTQ+ musicians, like FAKA, Angel-Ho, Queezy, Dope St. Jude, K.Dollahz, Umlilo, MX Blouse, and Lelo Whatsgood, who have become some of the most pertinent cultural ambassadors of a post-apartheid country Archbishop Desmond Tutu once aptly dubbed the “Rainbow Nation.” “But that community is dead now!” Moon says, only half joking.

Just as in most other countries, COVID-19 has robbed Cape Town—and South Africa at large—of vital queer spaces and creative platforms. Moon’s tone shifted to one of mourning when discussing the permanent cancellation of their favorite queer-friendly party in the city, PRIME. As a gender nonconforming artist, Moon described how affirming the ritual of attending was. “When you’re out in the world, people look at you weird or people ask questions, but if you’re in that type of environment, where everyone else is also expressing themselves freely, you feel at home. And you feel welcome,” they mused. Moon colored their memories by recounting the whimsical outfits they donned for the event, which included a hot pink, two piece Helmut Lang suit with a matching cowboy hat (which they describe jovially as “like Woody from Toy Story, but gay!”) and magenta hair. For Moon, PRIME was a platform for unimpeded expression, sartorially and sonically. “It was the only party where I felt truly safe and where people actually enjoyed new sounds,” Moon says, before ruefully adding, “The rest of the city is very homogenized.”

Although queer South African creatives are making waves on the global stage and altering the world’s perceptions of the country, Moon was eager to clarify that the shadows of apartheid still weigh heavily on Cape Town’s nightlife scene, explaining, “It’s still very much a boys club. [Bookers] don’t support people who go against the grain, or the real innovators who push the envelope.” Racism, homophobia, and transphobia are still alive and well after the dissolution of the white supremacist Boer regime that plundered the country for five decades. After such a staunch history of queer and Black erasure, it’s unsurprising that so many young LGBTQ+ musicians of the “Born Free” generation are so emphatic in their expression. “[LGBTQ and BIPOC artists] don’t get booked in the same way that straight, white men do. Even straight women struggle to get work here,” Moon says. “And the only time we are booked, it’s as tokens during Pride month or global protests. When those events are over, we go back to not having jobs.” Even before COVID-19, Moon said it was and still is nearly impossible for queer musicians to sustain themselves on art alone on their home turf. “People’s livelihoods are at stake,” they state.

But like so many queer pioneers before them, Moon has consistently managed to overcome the systematic and circumstantial barriers to success that queer Black artists face, not just in South Africa but around the globe. Remarkably, the tragic year of 2020 proved to be their most exposive one, career-wise, to date. Before the pandemic hit, Moon was already physically immobilized and in need of an emergency hip replacement. “I thought I was going to come out of the hospital, recover, and then be back dancing in the streets. But there was nowhere to go when I could finally walk again,” they recall. While recovering, Moon created their first EP, Martyr, which was released in the summer of 2020—a collection of Afrofuturist trance tracks that belong to a genre Moon describes as “spiral music.” Using various unorthodox, DIY samples (the track “She” incorporates iPhone recordings of Moon throwing forks and knives around their kitchen), Moon engineers a sonic universe that reflects their journey of healing and recovery. “I hear music in a lot of things that are visual,” they say. “When I add those sounds to my songs it adds a certain texture that can’t be replicated with certain plugins.”

By loading the content from Bandcamp, you agree to Bandcamp's privacy policy.

Learn more

As evidenced by Martyr, Moon delights in luring audiences towards the bleeding edge, towards a new, perhaps uncomfortable terrain. This practice extends to their approach to online comedy, which has been an equally potent exercise in the art of confrontation. Before Moon started pursuing music professionally, they were a well-known comic and critic in the Twitter sphere, whose bold attacks on hegemonic systems and unabashed honesty got them banned from the platform—a total of 11 times. After facing repeated censorship on Twitter, Moon began focusing on another digital project that’s also aggregated significant momentum this year: the Instagram account @Patiasfantasyworld. Moon is one of three admins who contribute memes to the humor page, which is a celebration of the explicitly (and exclusively) Black experience. “Harvesting” memes, Moon says, is a passion on par with music, “It’s modern art, and it’s comedy. We need memes in the MoMa!” The musician also revealed they use a burner Facebook account to find their funniest content, which usually comes from family members and other folks of older generations. “Aunties,” Moon reports, have proven to be the most reliable resource.

After the murder of George Floyd, however, Moon and the other @Patiasfantasyworld admins decided to shift their attention toward becoming a reliable resource, but with the far more serious aim of dismantling systemic racism. “You can’t laugh at our jokes but ignore our issues. Yes, we’re funny online, but in our real lives we’re stressed and depressed because they’re killing Black people—and not just in America. Black trans women are murdered at genocidal rates everywhere,” Moon said. The trio created an extensive anti-racism database and educational platform to promote the Black Lives Matter movement, which has since circulated extensively around the internet. “We worked hard to make it accessible for everyone,” Moon said.

When talking about their role as a co-curator on the account, Moon described themself as a “loveable agent of chaos,” but the term applies to all of their artistic outlets. Be it in their infectious tracks for isolated raves, gender parodying club kid outfits, or truly outrageous posts online, one thing is clear: Moon has a knack for turning moments of darkness and pain into humor, creativity, and light. And while the future of South Africa’s queer underground—and nightlife culture in general—remains in an indefinite limbo, Moon will keep us dancing and giggling, no matter how dire things get.

Cassidy George is a Berlin based cultural writer. You can find her on Instagram.

Photos by Luke Bell Doman and Jaimi Robyn.

Published January 21, 2021. Words by Cassidy George.

Follow @electronicbeats