ModeKollector: An interview with Dennis Burmeister, Depeche superfan

Dennis Burmeister is the über-collector of Depeche Mode memorabilia whose vast collection contains over 10,000 pieces and makes up the majority of our Depeche Mode Fan Exhibition. Growing up in East Germany, where DM had a huge and intensely loyal following, his access to editions and oddities particular to the territory formed the base of a 30-year accidental obsession culminating in exhibitions in four cities across Europe and a monograph book. We spoke with Dennis about the origins of the collection, his experiences as a Depeche Mode devotee, and get details of the exhibition from him and curator Martin Hossbach.

When did you first hear Depeche Mode? What song was it?

It’s hard to say exactly how and when I came to be a fan, but I do remember hearing “Pipeline” on the radio and thinking what an unusual song it was with all these sounds and samples—like the table tennis ball and the chanting sounds—and these crazy mixing effects. That was probably my first ‘lightbulb’ moment, although at that point I knew nothing about the band. It must have been 1983 or ’84.

Was that on East German radio?

I’m not sure, but I think it was on Western radio. At that time, we were listening to all sorts of music and recording it ourselves directly from the radio. There was this really big recording culture going on at that time.

But at that time it was illegal to listen to West German radio, right?

I can’t remember whether there were any regulations about the radio. We were doing all sorts of things at that time. A friend of mine used to go into the copy shop and photocopy pages out of Bravo magazine in postcard format, and then sell them openly around the city and no one gave him problems. There was also this TV program called Ronny’s Pop Show with a monkey with the voice of Otto Waalkes where I first saw video for “A Question Of Time”. That was in 1986 and probably my second lightbulb moment.

Would you say that the third lightbulb moment was when the Berlin Wall fell and you could finally buy all this stuff?

No. I was already buying things before. In mid-1987 there was a greatest hits album released in the East because they couldn’t agree on which studio album to release. The AMIGA compilation was a huge thing and I loved listen to songs like “Shake The Disease”, “It’s Called A Heart” or “Everything Counts”.

Was the greatest hits album put together just for East Germany or was it also released elsewhere?

I think the tracklist on that one was different and just for East Germany. They used the cover from The Singles 1981-85 but they changed around some of the songs. As I said, originally there were plans to release a studio album but there were financial limits to what they could do, and eventually it was decided to release a best of album. That was around April, 1987. I got a tape copy of that album at the time and I still have it. I actually stole it from the city library along with an Elvis tape.

You have a collection which now totals around 10,000 pieces. How did you manage to amass so much?

It grew over time. My friends and I used to swap tapes and things that like. I wasn’t just listening to Depeche Mode either. My dad was kind of a hippie and I grew up listening to the Stones and Beatles and Black Sabbath. He really tried to influence me musically. I had Shakin’ Stevens posters on my walls, but I didn’t put them up—he did! My dad was also really into music, so that sparked my interest, although my taste was different to his. I collected what I could get my hands on and what I couldn’t find in the East, I bought later after the fall of the Wall.

How did you find and buy things before eBay?

I just bought what I could find in record stores. There were record stores such as Cadillac that had pretty decent collections of electronic music, and that’s where I got a lot of my stuff. With the fall of the Wall, there was a massive surge in sales in the Eastern Bloc countries and you could see that in the stores. You could find everything back in those days. There wasn’t really any knowledge or interest in whether certain releases or pressings were rare, people were really just concerned about the quality of the music.

Did you also go to flea markets or things like that?

No. Sometimes there was a fun-fair in town, that had little stalls and was kind of like a flea market where you could find books and lot of second-hand items. They also sold records from the West there, but they were very expensive. A Stones record would cost 200 or 300 East German marks and that was just crazy when you look back at it today.

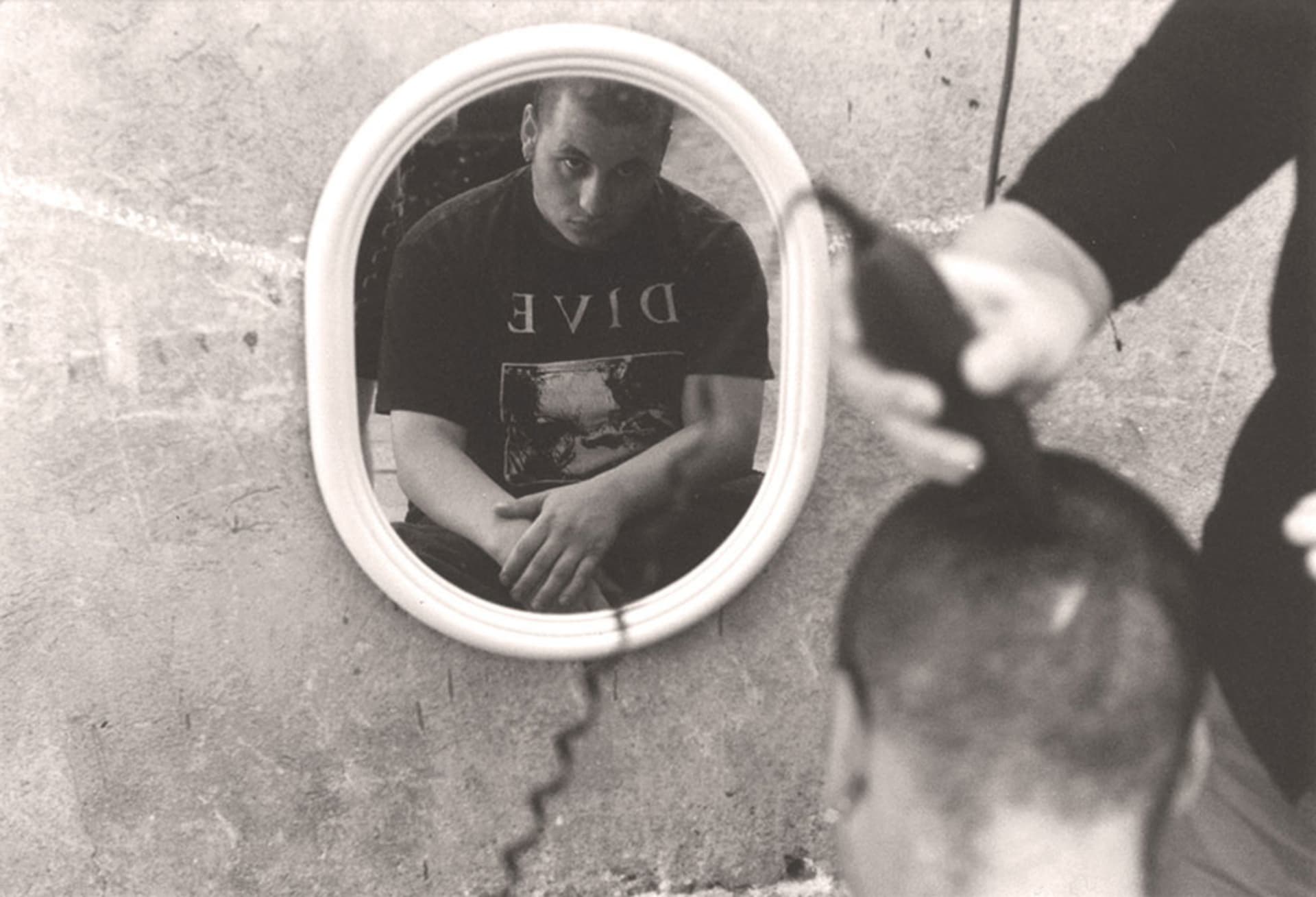

Dennis Burmeister in 1991, the year after Violator came out

You have built up your collection because you’re intrigued by the music, but it’s more than just that. You’re also interested in pop culture beyond the music, correct?

Personally, it really annoys me that the same stories about the band get transported from one press article to another. They all seem to use the same ideas and same tone. Since 1996, there was this increased focus on the whole drug story and then it was all about gossip and grubby stories about the band, and I just wasn’t interested in any of that at all. For me, it was about more than just four musicians—there was the whole team at Mute Records. You could write a whole book about Daniel Miller, and the whole Mute or Intercord story. Today’s mp3 generation probably can’t imagine what Daniel Miller did with Mute in UK or Intercord records in Germany and then everything else that surrounded it. These sorts of stories were what really interested me and got me involved as a kind of music historian. The whole success story of Depeche Mode lies in so many fields, like Martin Gore’s texts or the awesome sleeve designs that the band produced.

Let’s talk a little about the book and then the exhibition. People are saying that this is the first extensive monograph about Depeche Mode. How did you come up with the idea for this project and who did you work with?

With regards to the idea, I have a pretty good relationship with Anne Haffmans from Mute Germany. Around 2000, I was working on a website with people who had close links to Mute, and that was all really nice and interesting having a direct view of how it all works. Anne is someone who has a genuine interest in fan stories and how fans create cultures around certain bands and build up collections. She was the first person to say to me that I should make a book out of all the information that I had gathered over the years.

I made the book together with an author and historian from Leipzig called Sascha Lange. In 2008, for the 20th anniversary, he tried to get a documentary about the concert in East Berlin on March 7th, 1988 off the ground. I met him in the offices of Mute, and he wanted to get a bit of material and information from me. He was also doing interviews, and he wanted me to be there when he interviewed the then-tour manager of Depeche Mode. So, Sascha and I quickly become friends and that’s how the whole thing started. We spoke about it for ages before actually getting our act together, and after speaking with friends eventually settled on the idea of putting it out through [publishers] Aufbau Verlag.

Would you say this exhibition is important and necessary because of the passion of Depeche Mode fans? There really isn’t any other pop phenomenon quite like it, particularly with relation to East Germany.

There had been ideas previously to put together such an exhibition, but the band had resisted anything like this because they didn’t see themselves as a band that should have an exhibition in a museum or anything like that.

I’d like to talk to about Depeche Mode on the internet. From the end of the 1990s, when the internet really took off, fan forums started to appear bringing together people from all over the world. Did this really give the fan community a new thrust?

Definitely. I first really noticed it when Exciter came out in 2001— on the official website, fans were being enticed with little snippets from songs, particularly the first single “Dream On”. That was the first time that I can think of where the internet was really used to promote a Depeche Mode album. The culture then grew really quickly. Today there are hardly any secrets anymore. Whenever anything happens, the band is in the studio or something like that, there are people who see them and take photos and put them on the internet straight away.

Do you have any explanation for why that is with Depeche Mode, even today? People who are constantly posting on the internet are likely to be younger than 40, and it sounds like these fan groups are really continuing to grow—writing blogs in different languages and everything. It kind of sounds like a popular football team where fans are constantly speculating about every injury and every potential new player that the club might buy.

The band members themselves don’t really say that much, so they’ve kind of left all of the space for discussion about the band to the fan community. There are smaller bands that don’t really do much promotion or anything like that and just let it happen over the internet, and it’s the same with Depeche Mode even though there is such a great interest in them. I have no idea why that is.

I’d be interested to know how you were able to choose the 500 pieces for the exhibition from a collection of 10,000 pieces.

Martin Hossbach: Funnily enough, Dennis wasn’t really much of a help, because it’s actually quite difficult when you’ve spent so much of your life collecting all this stuff to pick out a selection that gives a good reflection of the broader picture. That’s why you need someone like me to come in any make some decisions. I am personally a collector of Pet Shop Boys items and, although I have much less stuff than Dennis, I know that I would have difficulty knowing where to begin if I had to put on such an exhibition. We worked together with exhibition architects, who suggested that we do a mixed layout—with some sections like in a classic natural history museum with cabinets that allow people to take a closer look at individual items, and then have other sections as ‘scenes’, which would be built like film sets where items would be arranged as they would have been used. The scenes will only be at the Berlin exhibition on the ground floor. Due to financial and logistical issues we’ll only have the natural history style sections in the other cities of the tour. In Berlin, there will be two scenes; the first will be in a recording studio and the second will be in a record store. The record store is modelled on the legendary Rough Trade store in London and the studio is modelled on the Hansa Studios in Berlin, where Depeche Mode actually recorded. In the studio you can see an original Emulator, a sampler, one of Martin Gore’s guitars, and a range of other machines and other things that the band used. There are also listening stations where you can listen to Depeche Mode songs, including the first demo tape that the band recorded. The record store is put together to give an impression of how the marketing of the band and other behind-the-scenes work was done by the label.

After it was decided to do the exhibition in this format it was easier to decide what items to use from the collection, because we knew what the restrictions were. Dennis and I sat down for two days and thought about how we could narrow down this selection that includes everything from Russian bootleg flexi-discs to fanzines from various countries, remixes, tour programs, promo material, everything possible. In the end, it also came down to a question of taste—really just choosing certain items based on how they look aesthetically.

DB: The exhibition isn’t just aimed at hardcore fans and collectors; that’s why it was important to get Martin involved because he’s not so deep in this whole scene and could pick out items that would appeal to more people.

MH: I think that the quality and the real strength of the exhibition lies in the fact that even if you’re not interested in the music, you can still learn a lot about pop culture, marketing, promotion, graphic design, photography, and much more.

DB: It’s also really interesting to look at how many opportunities the band were given that new bands these days wouldn’t get. These days if one or two albums flop, then bands get chucked out the window. With Depeche Mode it was different, the record label believed in them and stuck with them. It was a typically Daniel Miller thing, understanding the basic idea of the band and its potential. You can really see how much love went into it all. It’s also, in parts, an intensely colorful journey back in time, which helps dispel this image of the band as being somehow gloomy. For me, Daniel Miller has been one of the most important people in the music business for decades.~

The Depeche Mode Fan Exhibition:

Zagreb: 09–23.05.13, Galerija Klovicevi Dvori

Budapest: 11–23.05.13, Design Terminal

Bratislava: 15–25.5.13, Telekom shop in Polus City Center

Berlin: 7–20.06.13, Warenhaus Jandorf

Published May 05, 2013.