Mykki Blanco Talks To Lydia Lunch

Since the late ’70s, no-wave icon Lydia Lunch has been known for her no-holds-barred approach to self expression, be it political, sexual or a combination of the two. The creative mind behind Teenage Jesus and the Jerks has collaborated with a veritable who’s who of punk and post-punk artists, and in the process has become an inspiration for many a fellow musician and young art weirdo seeking to break out of their hometown for the big city. Despite being from two vastly different New Yorks, she and rapper/writer Mykki Blanco, whose recent mixtape Gay Dog Food was released via UNO in late 2014, are perfect foils. Blanco’s rise as an artist has seen him wear a number of hats, from occasionally cross-dressing rapper and poet to aspiring investigative journalist. And while Lunch has been creating art globally for over three decades—or “since before you were born, honey” as she put it to Blanco—both have the same experimental fire burning in their cores. The two bonded over wine at the Howl! Happening gallery in Manhattan before the opening of Lunch’s current exhibition, “So Real It Hurts.”

Lydia Lunch: One reason why I was interested in speaking to you is that I’m in drag every day. I thought it was also interesting that we both ran away to New York when we were very young. We already have this connection. We’re both, as I like to call it, non-mono-gender.

Mykki Blanco: I think I most identify with being a gay male. But what’s interesting is that before Mykki Blanco began in 2010 and 2011, I was living as a transgendered woman every day. What spurred it wasn’t anything that had to do with my sexuality; rather it was this creative Pandora’s box that seemed to open. One of the reasons I ran away as a kid and still do the impulsive things I do is because I’m an experience junkie. I’ll hop on the horse and ride into the dark cave, get bit by a scorpion and then be rushed to the hospital, but at least I did it.

LL: I’m an adrenaline junkie, which is why I’ve never become addicted to any other drugs because I’m riding on the natural high and that’s from experience. It’s why I also collaborate with people. Art, to me, is the self or the universal wounds. When I collaborate with people I want it to be this sacred space where no bullshit gets inside because bullshit is everywhere outside of it.

MB: What I’ve found now is that when I do choose to cross dress, I know how to do it so perfectly my body becomes something that gets catcalled on the street. Then I experience that feminine sex objectification. It’s so odd because I can have facial hair and go about my life this way, but if tomorrow I decide to wake up, shave everything, put on a wig, a full face of makeup, a padded bra and go out into the street, it would be a completely different experience. Knowing that everything is actually that transformable, it kind of messes with your mind.

LL: That’s where you and I are kind of similar: [grabs breasts] These are balls, honey. But this is a grand trick and the devil is a woman. I love being tricked out in this body because basically I feel like a faggot truck driver. That’s how I describe myself, but I look like this. It’s a lot of work.

MB: When I ran away from home, I wasn’t running away from a negative home environment. I was super independent. My mom actually still has the letter I wrote her, and I think I say something like, “I’m not running away from you. I’m running away to my future,” or something to that extent…See, Marcel Duchamp was such a huge influence for me. I actually wrote a narrative book of poetry before I started rapping called From the Silence of Duchamp to the Noise of Boys. That term actually comes from this European conceptual artist Vettor Pisani, who had a piece called All the Words from the Silence of Duchamp to the Noise of Beuys, as in Joseph Beuys. I switched it around to be B-O-Y-S. But Duchamp was super important to me because through him I realized at a young age that I didn’t have to be pretentious. Art didn’t have to be this foreign, serious, over-intellectualized thing. It could be playful…

LL: And absurd. It’s whatever you decide to elevate to art, which is both the best and the worst part of Duchamp. My favorite piece by him is Étant donnés. If you’ve never been to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see it, it’s stunning. It’s a huge barn door, so you walk into this room and there’s just a barn door with two peepholes. To me, this was such an amazing last statement that’s so multi-dimensional and so evocative and provocative. I’m a conceptualist—the Surrealists, the Dadaists, the Situationists, that’s my heritage. And that has nothing to do with punk rock, which I never was. It’s no wave. When you speak of any other kind of music, like disco or punk or country or opera, to some degree, you know their parameters. But when you say “no wave,” it’s less clearly defined. It was different from punk because it was a social phenomenon based on protest. No wave was about personal insanity in an asylum the size of a city where everybody was a lunatic, quite frankly. It wasn’t user-friendly and it wasn’t “we’re all in this together.” It was very isolationist. It was very this is me against everything.

MB: The ideology of going out of your way to move to somewhere inexpensive and dangerous isn’t so prevalent these days.

LL: Otherwise, Detroit would be overloaded with artists. I was there recently for a no wave panel at the Detroit Institute of Art with Retrovirus. And there are great people there. But pre-technology and pre-Internet—Haight-Ashbury in the ’60s, Chicago with blues in the ’40s, Paris or Weimar Berlin in the ’20s and ’30s—people always went to places that were pre- or post-disaster for economic reasons because other artists gravitated toward that. I think with the rise of the Internet, that geographical place doesn’t exist so much anymore.

MB: And everything is event based. I was having a conversation with a friend about how no city is cool anymore. Everything we do is based off of an event.

LL: This seems like the right time to drop a few facts about New York in 1977: Son of Sam; the Blackout with 5000 people arrested, all of Broadway looted. Hip-hop culture came out of the Blackout of ’77 because everybody stole electronic equipment. Many mafia dons were murdered. The first boy appeared on a milk carton, Etan Patz, and they just reopened that case recently. That’s just off the top of my head. My apartment was $75 a month. It was between two burnt-out buildings, garbage piles six feet high. They didn’t want to give it to me because somebody had electrocuted themselves with their TV by accident and their dog ate their face off. It smelled like death. So, I went to the botanica around the corner. They gave me a little bottle with a skull and crossbones, I shit you not, a few drops and the smell of death was gone.

MB: So, New York City, 2007. I moved into a storefront. There was this woman who had a store called the Art Fiend Foundation. Her name was Johanna Hofring, I met her as a runaway. But then six years later, when I got back to New York I was like 22, and I rented a room deep in Bushwick. My neighbor was this Caribbean man, who I don’t believe practiced voodoo, but he definitely chanted at night. Then when I was in New Orleans, I heard similar chants, which made me think it was voodoo. But anyway, I had to get out of the situation because there were fucking roaches in the building, and it was pretty disgusting. As in, like, furry roaches. I left, and Johanna and I had this deal. She had opened up this whole new store in Sweden, so she actually didn’t even live in New York. I was supposed to manage her store in New York, but I definitely didn’t manage it. I used it as an insane hangout. My friend Armand and all these boys would come and smoke angel dust there, which was all full of organic clothing…

LL: That smelled like angel dust? Best of both worlds.

MB: But they would steal stuff. I ended up having an insane situation where I was locked out and drunk, but I had left my shoes inside. I accidentally broke the glass door, but I didn’t have any money. The closest best friend I had was in Greenpoint [Brooklyn], so I had to walk across the Williamsburg Bridge, barefoot.

LL: Good thing you weren’t in drag barefoot. That wouldn’t have been a pretty picture.

MB: One of the things about crossdressing is that I actually learned about a New York underbelly that still exists. Times Square is actually still fucking sleazy as shit. Have you ever seen that scene in Sweet Charity where they sing “Big Spender”? There’s a club in Tribeca, in the Financial District, it’s still there, called Club Remix. It’s a basement club, a red room with paneled mirrors around and literally it’s just transgendered women and [cisgendered] women standing in a room and guys come to the bar. This exists. I discovered this through how I was living. The city will really throw you for a fucking loop.

LL: What about New Orleans? How long were you there?

MB: I was in New Orleans just for two months. I actually left because if I stayed there, I was going to become an alcoholic.

LL: They do drink hard there. I lived there for two years. I lived in New York from ’76 to about ’80, then went to L.A. for two years to work with Exene [Cervenka, singer for seminal punk band X] and I had a band when I made 13.13. Eventually I went to London to work with The Birthday Party and Rowland S. Howard. Then I came back to New York in 1984, and I moved to Spanish Harlem. I left New York in 1990 for good. I’ve been living in Barcelona for almost ten years. America is a fascist police state. I went to a country 30 years out of fascism, because [George W.] Bush stole the second election. I’m amazed nobody came with me.

MB: I live in L.A. now, but I was on tour for two years, so I didn’t really have a home when everything started with Mykki Blanco. I was literally living out of hotels. And this is the thing: I moved to L.A. in January but I’ve only lived in my apartment consistently for two weeks. My lease is for a year, and I enjoy living there when I’m there, but I’m kind of bored. Ready for this? Next month I’m doing an assignment in Nepal, but guess what? I’m going to climb Mt. Everest in drag. I’m not going to do it dangerously. I already told my mother, I’m not actually climbing Mt. Everest. I’m just going to do the trek to the base camp and I’m not doing any climbing. Whatever is two hours up, that’s where I’ll be. [This conversation took place before Nepal’s tragic earthquake.]

LL: I hope you don’t cause an avalanche with your spiked heels. Is anybody going to be sponsoring this?

MB: I’m going myself. One of the reasons I’m going is I got kind of mad. I grinded really hard the last three years. I think I have really tough skin, but the homophobia and the bullshit that I encountered in the music industry started to turn me off. I signed with this label based in the UK and Germany called !K7. Signing with them has been the best thing career-wise that’s happened to me. I have an advance and it’s good. But I told them, “You know what? You guys are signing me in a really fragile state. I need to recontextualize myself. I need new things to think about, I need new things to talk about. I’m going to accept this deal, but I need you guys to know I’m going to focus on some other things.”

I want to start focusing on my writing again and that’s why I’m going to Nepal on a writing assignment. I’m going to be writing about what I observe in my 41 days there through interviews with different people about what contemporary gay life is like in Nepal. From people who do sex work to middle class people. Through the Internet, I’ve already reached out to Nepalese hipsters. Actually, I feel like in the genesis of what you were doing, the world and society had much more respect for the time that it took to create a song. People didn’t want you to be on a hamster wheel pumping out content.

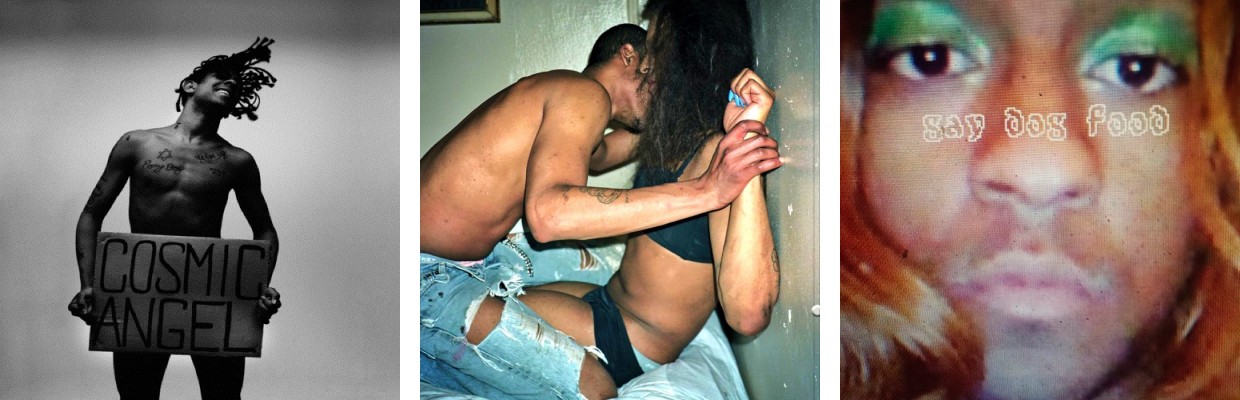

Left to right: Cosmic Angel: The Illuminati Prince/ss (UNO, 2012) was Blanco’s breakthrough mixtape; Betty Rubble: The Initiation EP (UNO, 2013) saw the artist upping his rap game while maintaining his experimental spirit; Gay Dog Food (UNO, 2014) continued to fuck with rap conventions and featured a collab with O.G. riot grrrl Kathleen Hanna.

Left to right: Cosmic Angel: The Illuminati Prince/ss (UNO, 2012) was Blanco’s breakthrough mixtape; Betty Rubble: The Initiation EP (UNO, 2013) saw the artist upping his rap game while maintaining his experimental spirit; Gay Dog Food (UNO, 2014) continued to fuck with rap conventions and featured a collab with O.G. riot grrrl Kathleen Hanna.

LL: I mean, who are they? Because I never listened to them anyway. Only through stubbornness, resilience and an incredible amount of discipline have I been able to do everything I’ve done. “Oh, how come you didn’t sell out?” You can’t sell reality out.

MB: But your music reached!

LL: Because I’m relentless. Because so much music is shit that people are going to reach back and find something good. The same way people reach back to Coltrane or Duchamp or Henry Miller because so much is shit right now and there aren’t many voices of individuals who are staying relentlessly true to their vision. My mood swings, my multiple schizophrenia, which is reflected in my music, my inner faggotry—it needs experience so that I can document it in lyrics or books or spoken word. Speaking about reality is not a popular commodity.

MB: I’m starting to realize that.

LL: I was so fucking aggressive and there was no precedent for that. We didn’t have many precedences for a screaming, tantrum-throwing bitch out there like she’s ready to box your fucking face in, which I was. I had many-a-fist thrown at my spoken word. My fists.

MB: There is a race to remain relevant because of the digital turnover. I was thinking about my projects sincerely, and they were coming from the heart, but how I felt they had to be executed left me no time to actually experience. As soon as it entered my body or my mind, I had to put it out. It’s like, “I need to release this song because I haven’t released a song in three months and people are going to forget about me.”

LL: That’s part of the generation you’re from and the technological turnover.

MB: But I feel like maybe some people are starting to wise up and that people want albums. People don’t just want this digital turnover because we’ve had so much of it.

LL: I don’t do the digital turnover. I don’t Facebook. I don’t do Twitter. I don’t want any part of that crap. This is my statement for Facebook: I’ve never had one because I knew it was surveillance from the word fucking go. You’re not my friend unless you look me in my fucking eye. And I don’t want to read a comment, I want to read an essay. Your comments? Put them on the toilet wall. This is my statement for Facebook because I’m going to start an account just for my exhibit at Howl! but I’m not running the page: “For all you Peeping Toms looking into the keyhole of all eternity, just so you know what I’m doing and you’re not. And you can’t leave a comment and I’m not your fucking friend.” It’s a surveillance device, and I don’t give shit.

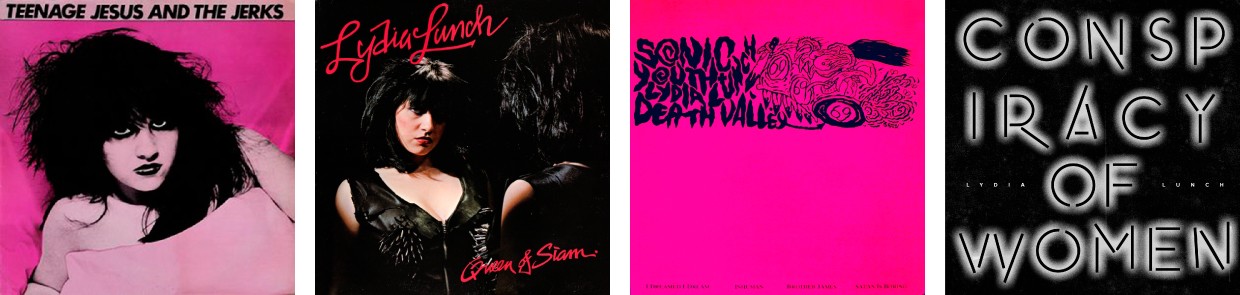

Left to right: No-wave classic Teenage Jesus and the Jerks’ self-titled LP (Migraine, 1979); the comparatively sanguine Queen of Siam (ZE Records, 1980); Sonic Youth collab Death Valley ’69 (Blast First, 1985); recently released Conspiracy of Women (Other People, 2015).

Left to right: No-wave classic Teenage Jesus and the Jerks’ self-titled LP (Migraine, 1979); the comparatively sanguine Queen of Siam (ZE Records, 1980); Sonic Youth collab Death Valley ’69 (Blast First, 1985); recently released Conspiracy of Women (Other People, 2015).

MB: I was just reading an article in National Geographic about how people are less adventurous because they can look places up on their phones, so every city in the world has so much surveillance footage. Even with Nepal, I’ve looked up something, but looking at every Google image, it’s just like, “There’s that temple.” And then when I fucking get there…

LL: That’s why people don’t have to do anything but sit at home and be their own armchair philosophers with their bad one-liners talking about everything you just did. I don’t think so. But I want to go back to the “no city is cool now” thing. I was talking to a friend of mine who has been nomadic for eight years, living as a traveling musician. And I’m like, “If we took $1500, we could get a triplex house anywhere but New York or L.A.” We don’t want to live in these cities because they’re the assholes of the universe. And she goes, “Yeah, but…” and she’s right, we don’t want to live anywhere else.

MB: Personally, something that I’ve wanted so far in this little artistic journey that I’ve been taking is a partner in crime. I’ve toured with other musicians, but having that artistic other… See, one of the things that performing has done, and maybe it’s my life path or my birth chart, but it’s kind of kept me single.

LL: I was celibate for two and a half years after a lifetime of promiscuity, which would top anyone you know. And that was shocking, the celibacy. A friend said to me, “You better get your legs above your head. No wonder you have a backache.”

MB: There’s a poem by the author Bob Kaufman that goes, “My body is a torn mattress, disheveled throbbing place for the comings and goings of loveless transience.”

LL: “My womb, a tomb, a sacrificial cunt. The more they kill, the more I fuck.” Lydia Lunch. To me, spoken word is still very important. The written word is still very important.

MB: I think slam poetry kind of ruined poetry. Maybe that’s a bit harsh; I do think there are some good slam artists, and when slam originated it was such a cool thing.

LL: When I first heard “slam poetry” I thought it was a physical thing and I was into it. Beat poetry? I want to beat somebody up.

MB: It created this stereotypical archetype that everybody associates with [mimics slam poet] “A poet speaking like this. And when I do this, my words are like this.”

LL: Well, I don’t do poetry. I do spoken word. That’s a real generic term but when I came to New York originally, I came to do spoken word. But a spoken word scene didn’t exist, so I just started curating shows with short acts of violence. One of my first solo shows was called The Gun is Loaded. Now I would have been arrested for treason. The first line was—and this was under Ronald Reagan—“It’s all about getting fucked. It’s about getting fucked up, fucked over, fucked around with or just good old-fashioned getting fucked. And you guessed it if you said the biggest dick of all was some octogenarian asshole who gets off on fucking the entire fucking planet.” This didn’t go down so well with those P.C. Soho News reading people because I was racist and I was sexist. Now, as a black man in a woman’s body who’s a faggot truck driver and a Sicilian, which makes me half-black, I’m sexist and racist? Give me a break.

MB: What was I accused of recently? Oh, I was accused of having an obsession with the “other,” because I don’t speak enough on police brutality or on issues that happen in the country. From all the traveling I’ve done, it’s hard for me to talk about injustices in America because we’re still a first world society. Something that happens in this country, as awful as it is, is not the same as something that happens where people don’t have fucking clean water.

LL: The reason why people don’t have clean water is because we denied them that fucking right. And the reason why we have to talk about the negative bullshit in this country is because we export all the fucking misery to the rest of the world. I have to continue to talk about it, and that’s why it’s important to me that Conspiracy of Women is being rereleased by Nicolas Jaar 25 years after it first appeared; or 30 years after I started complaining about this bullshit after being a child of the Summer of Hate, which is Charles Manson and the hate-fuck of America and Vietnam and Nixon and Kent State and the disaster that America was and the failure of the ’60s. It failed us and that’s why my generation was so negative. And out of that negativity, I chose to do something positive, which was to articulate, for those that have no fucking mouth, the rottenness that this country is. We don’t get the picture. So, I paint the picture with my fucking words.

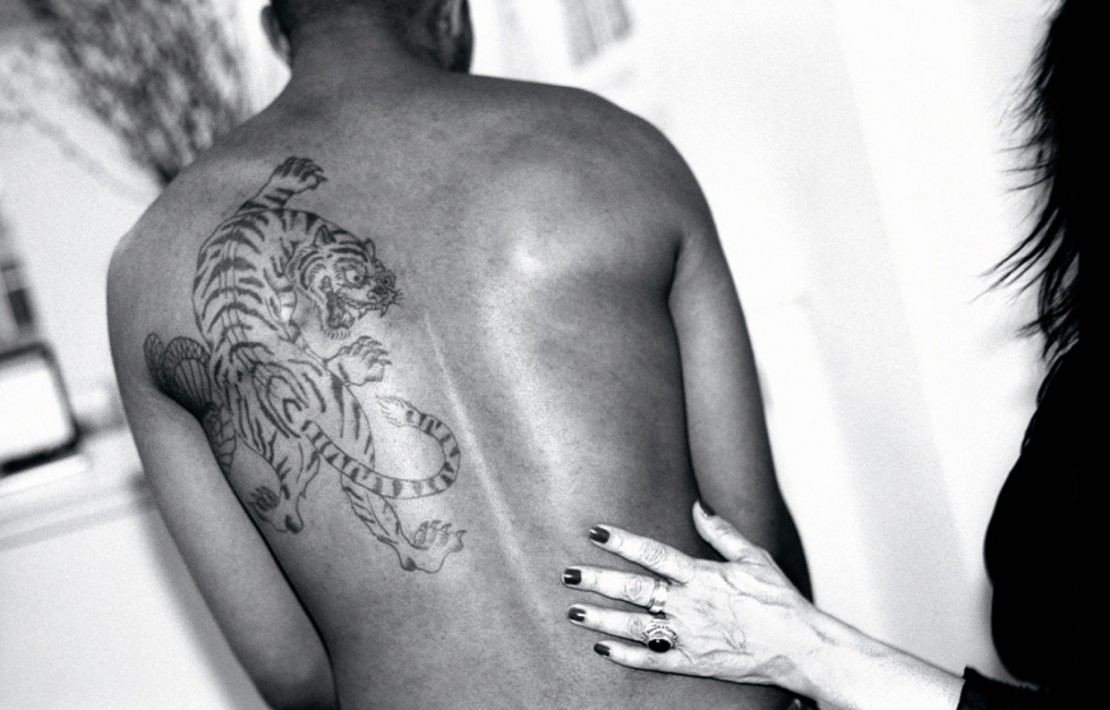

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from this issue. Images by Miguel Villalobos.

Published June 24, 2015.