Meet Nik Nowak, An Artist Who Makes Monster Sound Systems Out Of Military-Grade Tank Parts

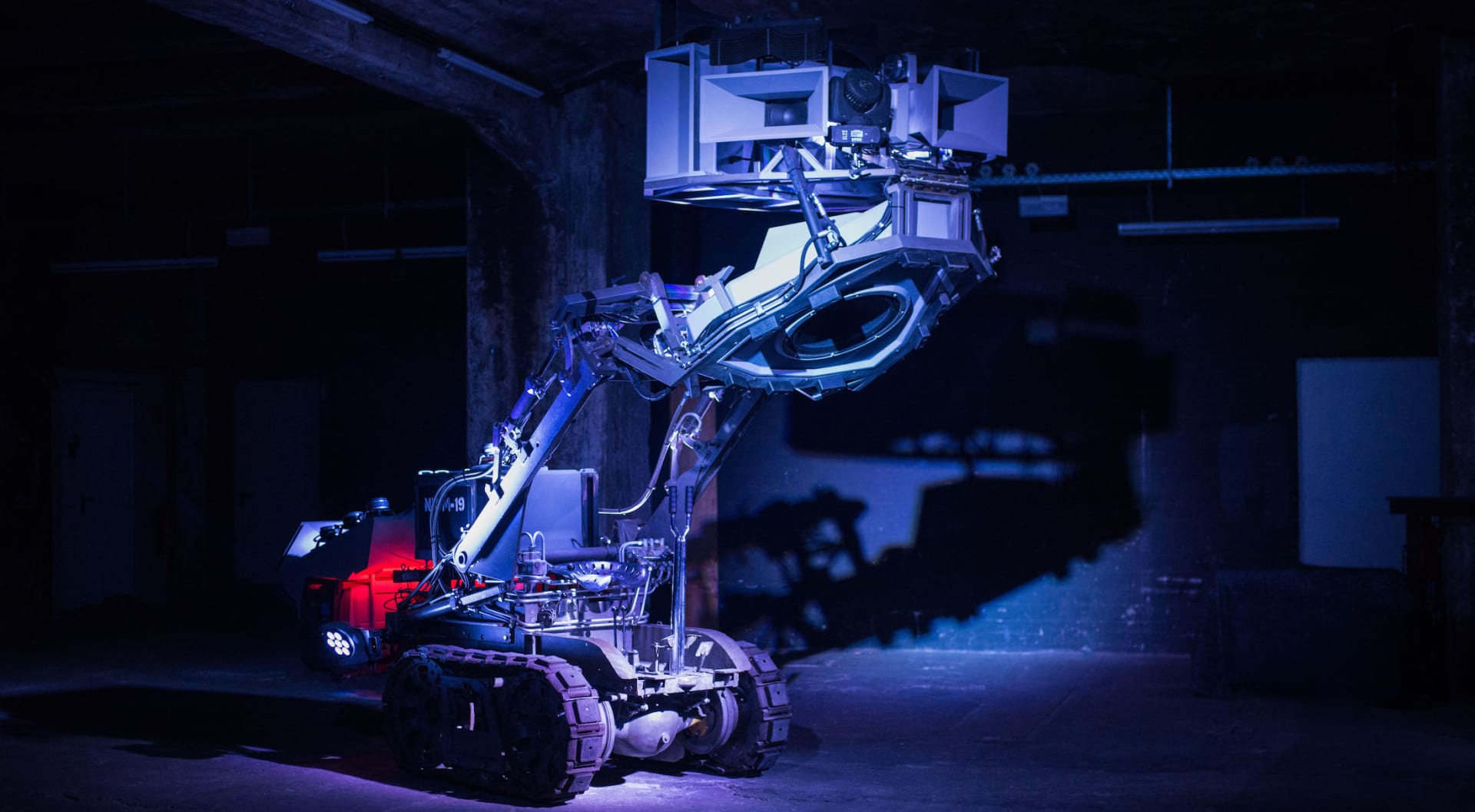

Nik Nowak's latest project, called 'The Mantis', is a massive sonic war machine that made its debut at CTM Festival's 2019 edition.

Nik Nowak is an artist who makes sonic war machines. His latest creation, The Mantis, is a two-ton structure with the body of a tank. Outfitted with a terrifying assortment of loudspeakers, it offers a commentary on the propaganda battles that have been fought and won with sound. The Mantis made its debut, with a collaborative performance featuring Kode9 and Infinite Livez, at this year’s edition of CTM Festival, which wrapped up last weekend. Staff editor Zach Tippitt met with Nowak to explore some of the ideas behind the project.

Believe it or not, the people who sell vintage military-grade tank parts on eBay can be a little sketchy. Still, according to Berlin-based artist Nik Nowak, it’s easier than you might think to procure the equipment needed to assemble a fully-functioning war machine.

Nik Nowak is a sculptor and artist whose most recognized work has centered around the construction of full-scale, multi-ton tanks. Instead of outfitting the machines with the standard range of artillery, however, Nowak uses them to house massive sound systems. His first creation, Panzer, and his new, recently-unveiled vehicle, The Mantis, splice together elements from the histories of global sound system culture and militarized sonic warfare. His work looks at the fine line between pleasure and pain to examine the psychological effects of extremely loud sound.

The Mantis debuted at CTM Festival 2019 with an installation and a string of performances inside Halle am Berghain. The project was inspired by events that took place on the border between East and West Germany at Studio am Stacheldraht (literally “the studio at the barbed wire fence”), where both governments utilized the amplification technology of the period to assault each other with sonic propaganda. Open for nine days, it featured a sonic face off between the Mantis and the Panzer, another sound system built by Nowak. At the performances, Steve Goodman (a.k.a. Hyperdub label founder Kode9) and Nowak controlled the machines while UK artist Infinite Livez provided vocals. We sat down with Nowak to learn what inspired him to create this imposing sonic behemoth.

Could you break down your methodology behind the creation of The Mantis?

My work is always bound to my research into sonic warfare and the use of sound as a weapon—that and the global phenomena of mobile sound systems. But Panzer was the first project explicitly focused on sonic warfare.

From there, I got more into the idea of using music and sound for propaganda. In this context, I learned about the Studio am Stacheldraht. There was a demarcation line at the Berlin Wall from 1961 to ’63, and the Russians and Americans were funding sound systems on each side, blaring propaganda over the border in both directions. The Mantis is directly tied to this bit of history.

To what degree are you using your military-grade sound systems for antagonistic “sonic warfare” versus actually inciting people to gather?

Both tanks play off of the concept of mimicry. Military sound systems usually play frequencies that are uncomfortable to disperse threatening groups of people. For example: the Long Range Acoustic Device (or LRAD) emits a tone in the range of 3,000 Hz, which is where our hearing is most sensitive and our pain perception highest. Reggae sound systems and my own systems actually have a filter that cuts this range out to allow higher volume and more comforting bass without pain. I mimic the form but use it to different effect.

In my work, I’ve always dealt with the military abuse of sound versus the civil use of sound and the development from military equipment to popular music equipment. For example, the vocoder was first used as a coding machine before it was used as a hip-hop machine. There’s a great book by Dave Tompkins about it called “How To Wreck A Nice Beach”.

The same goes for the history of amplifiers. High-power amplification was developed alongside systems for psychological warfare. There’s one particularly interesting story about a British-Jamaican soldier in World War II who was in the Army’s psychological warfare department and specialized in high-power amplification. After the war, he went back to Jamaica to use his skills to build amplified, heavy-bass sound systems and become one of the pioneers of the reggae sound system movement. You can see this connection everywhere, where people are empowered by equipment originally used for military purposes. For me, art has the potential to be resistant, and it’s important to know about the strategies of powers like the military so that you can resist. The concept of mimicry is about analyzing, understanding and “un-powering” those influences.

How have you used this technology to resist in the past?

I did these Panzer parades with DJ Spinn, DJ Rashad, Ikonika and Scratcha DVA where we drove the Panzer out into the streets waving these flags created by John Hartfield, a collage artist from the Dada movement. They say, “War and the dead are the last hope of the rich.” This was actually made after the World War I, when Hartfield’s work was focused on criticizing and warning against the militarism of the rising Nazis. Our parades were amplified demonstrations against weapons exportations into crisis areas and the ways the government and companies find ways of selling weapons into areas that have been prohibited by the Geneva Convention.

So what makes the Mantis performance different from your previous work with Panzer, and how have your past performances influenced it?

This project is in some ways a continuation of what I was doing with Panzer, but also it’s a coming together of many elements. There will be a fence in the middle of Halle am Berghain with the two tanks on either side. The installation is accompanied by video projections by Moritz Stumm that deal with the loudspeaker war and the use of propaganda sound systems to demoralize the soldiers and inhabitants of both sides.

Will the performance’s audio be more welcoming than what one would expect from “sonic warfare” sound systems, or will negative aspects of sound be explored as well?

You could see the performance as an audiovisual essay. The sound is cinematic, and the material approaches the potential of sound psychologically, physically. There are sections that can be irritating, and there are sections that are related to club music. But club music can be brutal. Even in the spectrum of what you might consider pleasing, there is a certain violence because of the pressure or sonic weight.

How do you feel about the painful and borderline-masochistic aspects of clubbing?

If you go to a reggae soundclash, you have to cover your ears to not lose your hearing, but you want to feel the full pressure. You want every cell in your body moved by the sound. After that, you feel shellshocked for days, but it feels like your whole body has been redirected.There are people who put certain metals in water and claim that it redirects the molecules in the right order. This is how it feels for me after a proper sound system night, like your body has been shaken until everything is evened out.

As for the borderline-masochistic aspect of clubbing, it may have something to do with overtoning the noise of the everyday. Over the past hundred years, humans got much louder, to the point that nature seems quieter, and our everyday lives got so noisy that now we need to produce self-selected noise. When you choose a club night, you want the music to be so loud that everything else goes away.

Additionally, I think intense volume works like a self-alarming system. You put yourself on high alert. It’s like calculated stress production or adrenaline production. When you’re on high alert, you’re a one man army prepared to face the offences of the outside world.

Why do you think people tend to be drawn to this experience?

You use the sound as armor. Earlier in my career, I built this piece called the Mobile Booster, which looked like a “pimped” car sound system, but kind of inside out. It didn’t have an engine, and the sculpture worked more like a wheelbarrow than a car. At the time, I was thinking about how when someone has a big-ass sound system in their car, it becomes a capsule where the sound level inside is so high, but it’s in a public space. Everyone outside of the capsule is affected by the leftovers—the bass frequencies—but inside the car, the person is in this high alert mode, pumped up, in a self-selected sound sphere. It’s his or her comfort zone, but for everyone else, its a threat. They’re dominating the environment. Everyone else in other cars is drowned in the acoustic sphere of that one person. It’s a sonic warfare strategy used in an “urban militia” way, an adaptation of military strategies in the urban subcultural context.

So we use high-powered sound to drown out the constant noise of our lives?

We not only have to deal with the real noise of the city, there’s also an abundance of input channels in the digital age that contribute noise that we have to deal with all the time. 60 years ago, in Germany, there were two television channels. Now there’s an endless amount. If you think about propaganda in the ’60s, there was so little radio and television transmission that whoever was the loudest spoke to the people. It was so simple back then. Eastern people were prohibited from watching or listening to Western television or radio. In North Korea as well, external information doesn’t come into the country. They control ideology by controlling input channels. It’s fascinating that this still works.

As civilians, it gets more and more difficult to feel independent navigating all of the offers from various channels. The ability to select gives us freedom, but you have so many vying for your attention that it’s difficult to know what to want or how to trust your intuition.

Is performing the sounds you want to heat at the highest level possible your way of forcing a “self-selected sound sphere”?

In my performance, I deal with these issues, but I’m not a dictator. I don’t want to tell people what to listen to. If you go to a club, it’s your choice. “This is where I’m going to be. This is where I’m going to escape from everything else. And this is what I’m going to listen to.” It’s not my intention to dictate a sound spectrum for everyone. That’s not my interest.

But all of these ideas are motifs in the performance. It’s quite complex, and the dimensions of the video and sound composition make this quite an extraordinary format. It has elements of a soundclash and a club night, but it’s also cinematographic and has narrative embedded in the sound.

When you have two sound systems facing each other vying for loudness and trying to be heard, how important is setting up the performance space for sonic clarity ?

They’re not playing simultaneously all the time, it’s more of a dialog. I see them as mono sound systems being played like instruments. If you have an orchestra, and there is a contrabass and a drum, you wouldn’t be worried about the frequencies of the drum cancelling out the frequencies of the bass. This makes more sense than seeing them like a PA system installed in a specific room, which tries to create an optimal neutral, linear sound in the space. As long as we compose the music for the sound systems, they work more like instruments.

Physically speaking, how did the construction of Mantis differ from that of Panzer?

I wanted to have more brilliance in the middle and high frequencies, so I decided to use a horn speaker system on the Mantis. It also broadcasts in 360 degrees.

On an acoustic level, it’s completely different. I love the bass on Panzer because it’s relatively simple and compact. The Panzer is very functional as well. It works as a mobile sound system. You can drive it. The new one is such a stretch between an absurd, mechanical old timer—its body is from 1963—and a modern system. It’s trying to bind future and past, so it’s kind of a utopian project. I wouldn’t use it to drive long distances. Mantis is so much more technically advanced than the Panzer, but at the same time it’s so anachronistic in its mechanics that it’s completely absurd and extreme.

Was the Mantis’ ability to rise up into a threatening, fully-extended position a purely aesthetic choice?

It also has a very important acoustic benefit because the middle and high speakers can broadcast much further away. The horns need to be above the crowd. While Panzer is a very typical sound system shape—it’s like a wall—the Mantis benefits from being able to play sound in 360 degrees and from above the crowd.

When you think about it, taking three and a half years on a sculpture, the process is very intense. It’s this morphological process with a million decisions involved. If you think about product development, the decisions are made practically. Here, you add a million extra artistic decisions. It becomes a very complex object, and, in the end, each object is unique.

How did you develop the Mantis‘ militaristic, threatening shape?

Most of the design comes from the original concept of mimicry. For example, if you think about camouflage patterns in fashion or the way we absorb militarism into pop culture, absorbing tank design is just another step.

I also have a personal fascination with insects, especially their shapes. So there’s also an element of biomimicry in the design. If you look at nature in terms of scale and change only the scale of an insect, it becomes terrifying and alien to us, even though it’s from our planet, and some of them are hundreds of millions of years old—much older than we are. This fascinates me: when something becomes really uncanny or frightening only because it’s so hyperreal. I try to achieve the same effect in my own objects. It’s something that’s absolutely plausible but completely shocking.

And if you actually take it apart, it’s composed of regular things. If you look at human perception, we really depend on being used to something. We’re completely overwhelmed when something is new for us.

How will the collaborative aspects of the performance play out?<

Kode9 wrote the book Sonic Warfare, which I became aware of when I was building the sound tank. He also translated bits for Panzer’s unveiling, and we have been meaning to work together since.

Infinite Livez, the MC, is from London, but he also studied fine arts, like me. His performance style is incredibly unique. You can tell he’s thinking in several dimensions. He works on graphics, and his idea of making music is quite unconventional. It’s easy for us to work together because we both work a lot with associations. In the end, however abstract the work appears, it always contains a level of narrative. Working with someone who understands this way of thinking makes the process more like creating an image than just music production.

In the Studio am Stacheldraht, there were operators in cars who read news to the East side. Then someone from the East would answer through the loudspeakers. They didn’t use recordings because they wanted the soldiers on the other side to know that they were spoken to personally. The spoken word was important to the operation, so Infinite Livez will MC live through the systems during the performance.

Moritz Stumm, who created the visuals, is a long-time collaborator of mine, and we have been working on collaborative audio-visual performances for over a decade. I call him the “inside crew” in the tank performance. The video synthesizes all of the ideas behind the performance. It includes the Studio am Stacheldraht, the propaganda, the psychological potential of sound and the world-wide phenomena of mobile sound systems.

Do you feel like this performance is a fitting culmination to the years of work you’ve spent on the concept?

It’s a one shot performance. It’s never been done before. Having those two (gestures to the tanks) in a duet, not just a DJ set or a soundclash—there’s quite a lot of things that come together there. It’s bound to be quite a ride.

Published February 07, 2019. Words by Zach Tippitt, photos by Camille Blake.