Oblique Strategies for Understanding Brian Eno’s Latest Reissues

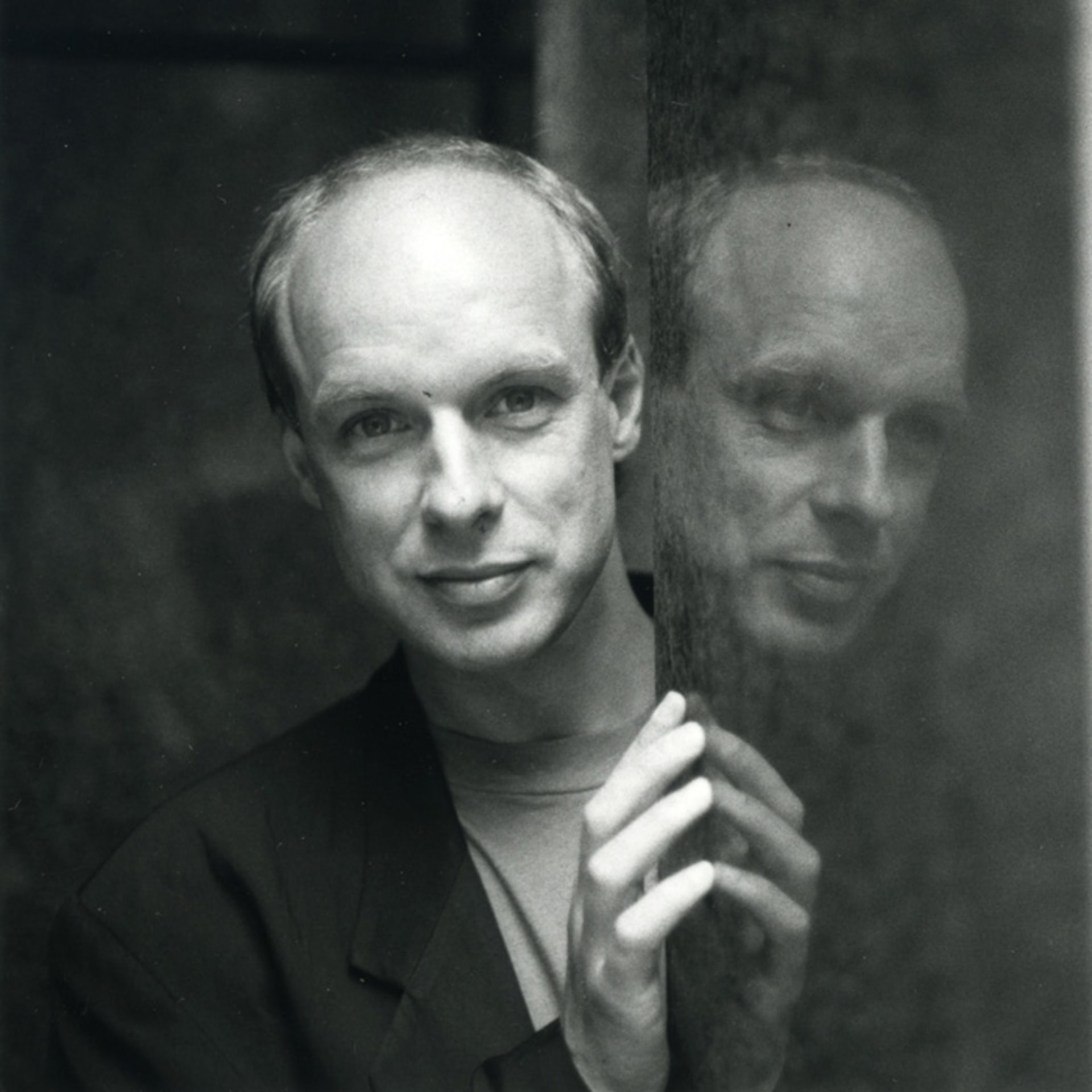

Aaron Gonsher explores the ups and downs of Brian Eno’s work through the lens of four recent reissues that dropped December 2.

What is the reality of the situation?

When Microsoft released Windows 95, the operating system sold 40 million copies in the first year, and by 1998 it held over 50 percent of the global market share. The program’s start-up sound thus became ubiquitous in homes around the world, and the brief sequence was created by Brian Eno, an artist with so many diverse occupations that referring to him solely as an icon of ambient music and pioneer in the field of studio production seems like a disservice, even if both honorifics are accurate. A marketing agency had provided him with a list of more than 100 adjectives, including “futuristic,” “emotional,” “sentimental,” and “optimistic.” 20 years into his career as a self-proclaimed “non-musician,” Eno was perhaps more equipped than anyone to satisfy such requirements, as his music had proven time and time again to be an ideal and elusive mix of futurism and classicism, familiarity and foreignness—in a word, universal.

My family was one of the millions who purchased Windows 95, and so years before I knew anything of Roxy Music, the Talking Heads, U2, or any number of bands on which he had left indelible sonic fingerprints, or even who he was himself, sounds made by Brian Eno were already part of my day-to-day existence. I would hear Eno’s work in short bursts in my living room, every day.

Look closely at the most embarrassing details and amplify them.

The four solo Eno albums now receiving reissues on All Saints—The Shutov Assembly, The Drop, Neroli, and Nerve Net—are not his best. The press release for these reissues, which were originally recorded between 1992 and 1997, trumpets how comprehensively they represent Eno’s various styles with descriptors that hail his “exquisite ambient miniatures,” “extended drones,” and “polyrhythmic funk.” The embarrassing detail is that Eno has done all the stated styles better elsewhere. These reissues are a boon to completists because they include over three hours of unreleased music. But to the casual listener, those bonus LPs run the risk of appearing as unnecessary additions to less-than-sterling albums.

State the problem in words as simply as possible.

I feel somewhat guilty for disliking even the least impressive pieces in Brian Eno’s catalog, a hesitance to criticize I don’t have for any other artist. How do you approach “minor” works by a “major” creative force? Criticizing a substandard Eno album feels a bit like walking into the Sistine Chapel and complaining about scuffs on the marble floor; the clunkers appear as minor distractions when measured against the titanic impact of his overall contributions to recorded music. Yet the urge to stifle my negative opinions based on a presumed stature of untouchability is a position I imagine Eno himself would discourage.

Balance the consistency principle with the inconsistency principle.

Based on a career of restless genre-hopping and a general demeanor of detachment from trends, these reissues undeniably benefit from Eno’s fans giving even the least of his output the benefit of the doubt. Many of his releases are automatically assigned a level of objective quality that can surpass their actual emotional or musical impact simply based on the fact that the music sprung from the skull of Professor Eno. What might be deemed missteps coming from other, less established artists become artistic pivots to Eno acolytes, with each one significant as added chapters in what would have been a legendary career even if he’d stopped making music in 1981.

The only expectation of Eno is unpredictability. The only pressure he faces is to evolve, but even that seems self-imposed. He works without external influence from critics or commercial demands. At the beginning of December, Eno won €10,000 as part of the Giga-Hertz Award for Electronic Music presented by German broadcaster SWR, for reasons partly described as “his lifetime of musical transgressions.” Rarely is unpredictability and breaking the frame rewarded with such critical vigor as Eno has experienced.

Emphasize differences.

These reissues are admirable because they highlight the diversity of Eno’s abilities, even if the execution is sometimes faulty. Neroli, a continuous ambient work, is the strongest on offer, the type of exceedingly lovely composition Eno must have stockpiled in terabytes, ready to release at random for the next 50 years. The skill with subtle accretion and disintegration that made him an ambient icon is also amply evident here and on the bonus material, another hour-plus piece called New Space Music. It sounds unbounded by a specific time period or style. Beginnings, middles, and ends are structurally superfluous – New Space Music is a pool you can jump into in any season and the water temperature remains the same. Stasis becomes beautiful.

The Drop pursues a similarly meditative state with jazzy electronic music, yet it’s sanitized by comparison. With the exception of two tracks that casually stroll past the 18-minute mark, most of these drops hover in interlude territory. Despite an assorted melange of pleasing sounds, such as the moaning in “Dear World” or the jumbled tones in “Targa Summer,” The Drop is all foreboding with no payoff.

Do something boring.

The Shutov Assembly is named for Sergei Shutov, a Russian painter who used to work while listening to Eno’s music but had difficulties accessing it in Soviet Russia. Eno, who originally studied to be a painter, obviously has a knack for these sorts of placid excursions. This could be Music for Airports if your plane suffered more turbulence and the stress of delays. It’s fitting that it was named for a painter who used the music functionally, as similar sonic threads showed up in the soundtrack of Eno’s travelling installation 77 Million Paintings. Experiencing that work was like watching grass grow in the best way, with endless visual permutations casually introducing themselves regardless of any attention you paid them. With both 77 Million Paintings and The Shutov Assembly, it’s difficult to stay engaged and yet disappointing when they music fades.

Discover the recipes you are using and abandon them.

Brian Eno’s current website is strange. It’s as if the only music he’s ever made are these albums now getting reissued. In the context of the Oblique Strategies, a collection of koans and directives written by Eno and Peter Schmidt in the mid-1970’s to jolt them out of complacency in the recording studio, such forward focus is unsurprising.

Like Eno’s career, the Oblique Strategies have gone through various iterations and transitions since the first edition was released in 1975. Now in their sixth edition, the Oblique Strategies are subtitled “over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas,” and they are a procrastinators dream and nightmare, both for how they can encourage random pivots of creativity while emphasizing process and effort rather than final result.

These bite-size pieces of guidance and obfuscation are like a Rosetta Stone for decoding the aforementioned stochastic elements of Eno’s career, while also serving as a concrete example of the intellectual freedom he’s been afforded. His music is unburdened by contemporaneity and, in the case of these reissues and numerous others from his career, stylistically unfashionable. These worthwhile dilemmas surely deserve some of the credit for the entrancing individuality he’s managed to achieve despite that.

Trust in the you of now.

One of my favorite albums of 2014 was High Life, the second LP Eno released this year in collaboration with Underworld vocalist Karl Hyde. While their first, Someday World, was anodyne, High Life is a wonderfully bubbly album, indebted to the namesake African genre and crammed with jangly guitar, tumbling drums, and an ecstatic energy. It’s so fun that it’s almost surprising it came from Eno, especially in the context of these generally grey reissues. When listening to High Life, I was struck again by a sense of guilt for enjoying the “easier” work, compared to the intricacies of The Drop or the mellow waves of The Shutov Assembly.

But for all his potentially impenetrable concepts or compositions, Eno’s success is ultimately due to the humanity he extracts from the complex conceptual underpinnings, an infectious enthusiasm heard in the imperfections, divots, and knots of whatever he’s singing or making that day. These reissues don’t immediately gratify, and they aren’t classics simply by nature of coming from Brian Eno. However, like everything Eno does, the music is presented with such earnestness and an obvious devotion to the task of creation that even basic attention results in a plainspoken joy. Worthwhile dilemmas, indeed.

Words by Aaron Gonsher.

Published December 19, 2014. Words by EB Team.