Reporting Live From Berlin’s Exploding Open-Air Scene

After a wave of criticism of outdoor parties, Nathan Ma gathers perspectives from organizers, party goers and Berlin's Clubcommission.

In early March, it became clear that it was officially time to evacuate the dance floor. As countries around the world scrambled to flatten the curve, an outbreak of 17 cases of COVID-19 was traced back to Trompete Bar in Berlin, with another partygoer testing positive after attending a party at Friedrichshain club Kater Blau. By March 13, Berlin’s mayor ordered the city’s bars and clubs to close temporarily, but in one of Europe’s club culture capitals, the party never really ended.

The club closure hit Berlin as spring turned to summer—a changing of the guards usually marked by garden parties and open-air raves cobbled across the German capital. While clubs closed their doors for what soon became an indefinite leave of absence, the city soon swelled with a network of underground raves on the banks of local lakes and deep in suburban forests and public parks. “It’s kind of an altruistic act that they’re doing this,” says Irina*, 32, who attended an open-air at Hasenheide–a popular park for open-airs just south of Berlin’s city center. “I actually had an amazing day, and I feel like something about it recalibrated my mental health—that kind of ambient boredom has gone away since then.”

Organized independently and communicated through Telegram, Facebook, and other messaging services, these parties have helped keep the city’s spirit alive. One open-air regular shows me an encrypted chat lovingly titled “Raves” in which strangers send each other GPS coordinates to link up for a late-night dance; two different partygoers recount settling into parties by local rivers and in the woods before realizing naked tea-parties were taking place in the immediate vicinity.

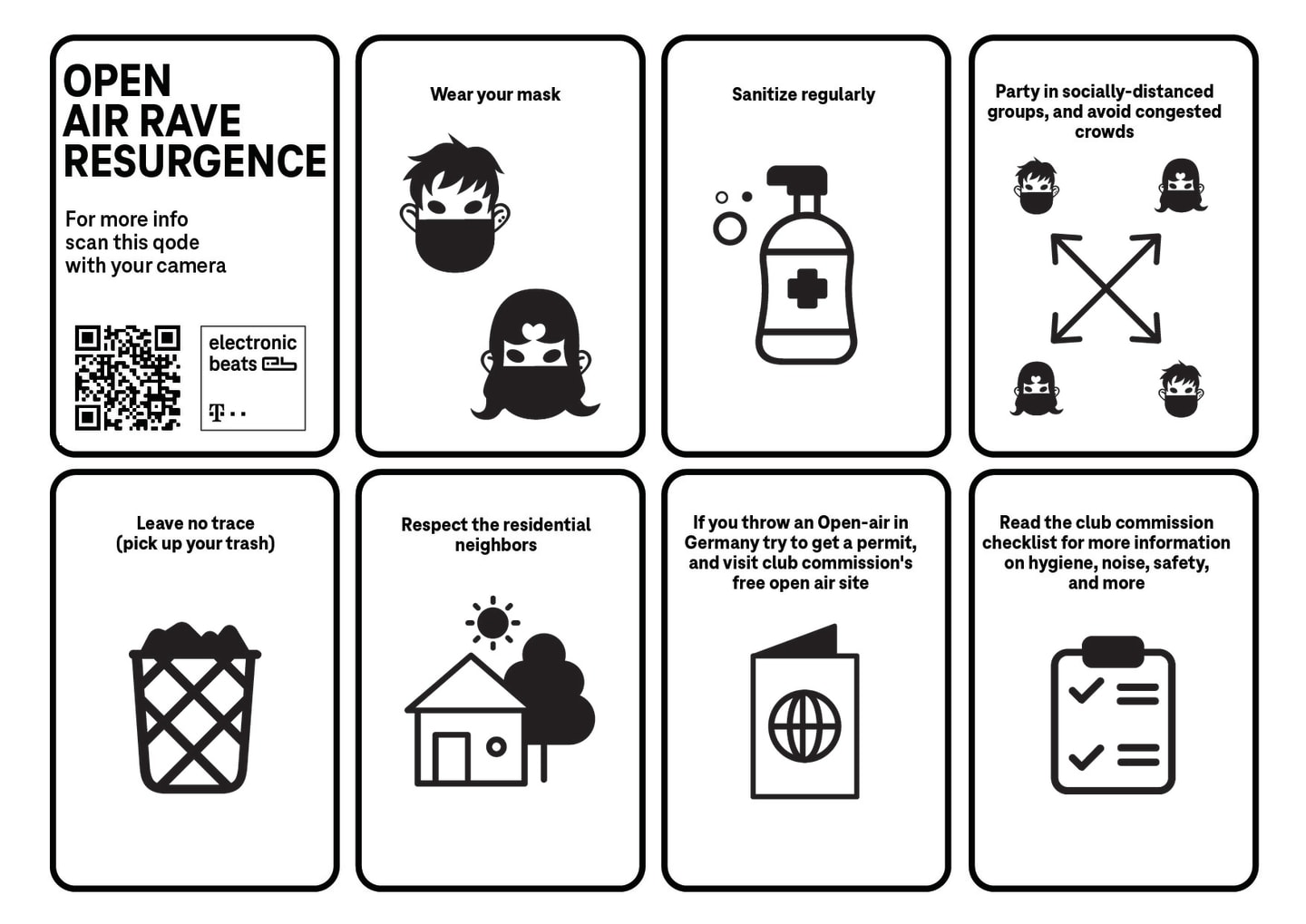

Erich Joseph, who works at Berlin’s Clubcommission, says that there’s no knowing how many open-air parties are being held, both now or ever. He says, “A lot of open-airs occur underground and on private channels. That’s how the open-air scene developed and is still alive.” According to Erich, the fight to keep open-air parties open in Berlin predates the current crisis: In 2014, the Clubcommission launched the Free Open Air initiative to work alongside organizers and government officials to create safe, legal, and free events targeted toward young Berliners. In light of rising health concerns, they updated their guidelines in June to include recommended hygiene measures to prevent the transmission of COVID-19. The recommendations were tailor-made to keep clubbers safe in a pandemic: They include providing designated hand-washing stations and keeping extra face masks on hand for those who need them, as well as staying up-to-date with the current transmission rate in Berlin.

Holly*, 24, tells me that she turned down invitations to open-airs because of COVID-related concerns at the start of the summer. “The rave was in a forest in Brandenburg, and the idea of getting a regional train potentially packed with ravers with a chemically-lowered sense of personal boundaries seemed overly risky,” she says. “I think people need to be responsible for each other and take precautions before doing substances in the wild,” agrees Sally*, 29. “You are not in the main city or at the club, and if someone passes out in the woods, it could go undetected. The thought of that haunted me days after the party, and thankfully we did not have any incidences. But it is a serious possibility.”

“The rave was in a clearing in the woods outside the ring. It was an old hunting ground, by the lakes on the edge of the Berlin city limits,” Sally explains. For them, hosting an open-air proved to be more complicated than they had planned. They followed the Clubcommission’s suggestions—masks, hand sanitizer, sign-in sheets for contact tracing, and plenty of reminders to maintain socially-distanced included—but found that leaving the forest as it was beforehand proved to be a surprising challenge. “Clean up was pretty intense: the cops shut us down around 11 P.M., and everyone scattered. Very few people stayed to help us clean and pack up. Also, the cops would not let us turn our generators back on to use lights to help us clean,” they told me. Sally says that the need for efficient waste disposal became apparent quite quick and advises that contacting the municipal trash collection service is among their top tips for future raves. After cleaning up what they could in the dark, they returned the next day: “I had nightmares of all the trash bags we had after the rave—it was a lot of sorting to do.”

“I’ve only been camping a few times in my life, but like everyone says ‘leave no trace.’ So, you know, I brought a couple extra garbage bags and the event organizers had trash bins,” Andy, 34, says when I ask him how he prepares for an open-air rave. “I don’t know if there’s a better way, but the way that the police break things up encourages leaving trash. The police come in with flashlights, and they intimidate people”.

The Clubcommission hopes that by streamlining the bureaucratic process that organizers face when planning an open-air, they can also better advocate for the city’s top concerns: The protection of green spaces and respect for neighboring residential zones. On July 26, the Berlin Polizei claimed that a party with upwards of 3,000 guests was hosted illegally in Hasenheide. Photos published in Tagesspiegel the following day show beer bottles, plastic bags, and takeaway containers spilling out of a public trash bin. “There were way too many people, and the areas around the speakers—which mainly seemed to be people’s Bluetooth speakers that they’d brought themselves blaring out techno—were totally packed, and it was too much,” Holly tells me. She visited Hasenheide shortly after leaving a party on Tempelhof, another popular park both during the day and occasionally after dark. “People were dancing in twos or threes and keeping their space, it was actually really lovely. The Polizei and park rangers drove by at various points and didn’t stop, so they can’t have been too concerned.”

“In the evenings the park isn’t really any more crowded than it is during the day,” says Andy, who was at the party at Hasenheide on July 26. Before dark, the park is a popular hangout zone for picnics, lawn games and after-work drinks. As Andy says, “I think some of the criticism of the people partying is just because it’s easy to criticize. I don’t see people breaking social distancing rules anymore than I see them breaking them on the street,” he continues. “I think there’s still an apprehension about strangers because we know that it’s during Corona times.” Irina agrees, saying, “It’s more of a moral sense of your own rules that you’ve already established a bit in advance, and one that you’ve established for months as well.”

The dissonance between personal and public responsibility is an issue of global proportions: Across the world, private parties and open-airs are being held, often in defiance of local lockdown restrictions and government advisories. For some, these parties are a moment of self-indulgence; for others, they represent an opportunity to fill in the cracks for performers and organizers who are feeling the cultural loss that comes with the closure of clubs and cancellation of festivals. Still, the lack of guidance on how to safely and legally host public events remains a challenge, and one that the Clubcommission hopes to fix quickly.

“The open-air season is going to be finished in two months,” Erich tells me. “On the one side, it is and has been very important for new artists in the city to have a stage and share their music. This platform enables them to become important authors in the electronic music scene. On the other side, the open-airs are a good short-term solution for the given circumstances in the electronic music scene,” Erich tells me, continuing, “Our main goal as Clubcommission is to represent the interests of the Clubs. Nowadays, this means surviving the crisis. With the Free Open Air Initiative, I hope that the cooperation with Berlin’s districts continues, so that more places can be used for legal open-airs.”

He adds that creating a clearer bureaucratic process for hosting open-airs is the first step towards creating safer parties during a pandemic: “On the other hand, I hope that the procedure of getting a permit for a place can be centralized—that’s one of the main reasons a lot of people don’t do it.”

“It’s a totally different ball game than working in clubs, where everything is provided for you,” Sally notes. In addition to providing safety and hygiene protocols to reduce the risk of transmission, their team did everything themselves—from sourcing speakers to looking after guests and keeping an eye on the noise levels for the neighbors. Sally continues, “The basic considerations start with power, weather conditions, difficulties at the location, local law enforcement, and local residencies—and the list goes on from there.”

But was it worth it? As Sally says, “It was fucking beautiful”.

Nathan Ma is a writer and critic based out of Berlin for The Believer, The Outline, i-D and more. Find him on Twitter.

*Names changed to protect the privacy of interviewees.

Additional graphic design by Sofia Apunnikova and Ekaterina Kachavina

Published August 11, 2020. Words by Nathan Ma.