Rewind: The Clash and Punk Rock in Post-WWII Scotland

Roual Galloway could be considered both an archivist and driving force in UK club culture. He’s filled roles as a promoter, record collector and occasional producer and created the storied Faith Fanzine with Terry Farley. And like many respected dance music authorities, his musical roots date back to punk. Here, he talks to writer, DJ, label head and Hard Wax mainstay Finn Johannsen about the anti-establishment mythology of garage bands and his all-time favorite track by the Clash, “Garageland”.

So what was your first encounter with “Garageland”? Listening to the radio as a teenager?

I got a copy of the first Clash album in 1979 from a record shop in Edinburgh called GI Records when I was 11. My dad had done some work for the owner and he was paid in vinyl, which meant that my sisters and I had three records each to choose from the stock. I can’t remember what my sisters chose, but the three I selected were The Ramones’ It’s Alive, The Skids’ Scared to Dance, and the self-titled Clash album. At the time we lived in a new Scottish town called Livingston. Later in life I realized that all post-World War II towns are built in three stages: building houses, attracting people and offering jobs. We moved there in ’78 in between stage one and stage two. This meant that unemployment was high and the youth were disenfranchised. Like most new towns, it was badly designed and architecturally awash with concrete grey. Punk seemed like a natural rebellion against the injustices imposed on the youth of Livingston and had a massive following there. A local punk band called On Parole used to cover “Garageland,” and I suppose it became ingrained in my consciousness from that. I saw the Clash live for the first time in 1979. I’ve always liked the sentiments of the lyrics, of standing up against selling out and of doing things for yourself.

Had you ever heard something like it before, or was that your first experience with punk?

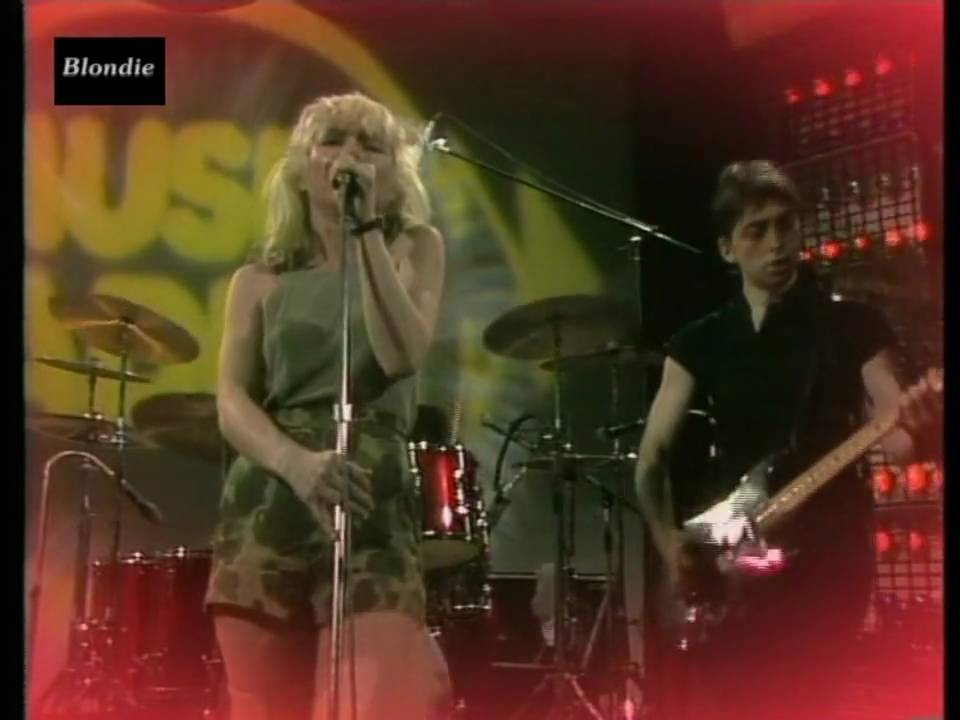

I was aware of punk in 1977, but I was too busy kicking a football about and chasing girls at the time. One of the first records I bought in 1978 was “Denis” by Blondie. Unfortunately, the other two were “The Smurf Song” and the Official Scottish World Cup song of 1978. I bought these while living in Nottinghamshire just before we moved to Livingston, Scotland. There was no escaping punk in Livingston.

I have to ask this question: Why the Clash, and not the Sex Pistols?

The Sex Pistols released one proper studio album in 1977, and then Rotten left. They were never the same after that, although the cash-in albums were hugely influential at the time of release. The Clash, on the other hand, released six studio albums in their existence. They matured with each album, apart from Cut the Crap. My one regret is that I didn’t see them perform live at the time. If I had to choose between the Pistols and the Clash, it would have to be the Clash every day of the week.

“Garageland” was the last song of their debut album. Did you like the album as a whole, or is this their standout track?

The first album is filled with classic song after classic song. From the opener, “Janie Jones”, to “Garageland”, it’s all thrillers with no fillers. How can you not like an album that’s as strong as this?

In terms of lyrics, Joe Strummer said the song was a reaction to an NME critic writing after their second gig that they “should be returned to the garage immediately, preferably with the engine running.” But it was also a statement against accusations that they were selling out when they signed to a major label—a quintessential dilemma for a newly successful band. Did they solve it?

Arguably not! They did, however, take control of their own imagery with the art on their sleeves, t-shirts and posters. They also refused to perform on Top of the Pops, which was Britain’s biggest music show at the time. On the other hand, later in life they’ve allowed songs to be used in advertising. Also, the corporate machine of Sony has worked their back catalog with great regularity. The fact that the Clash signed to CBS/Sony has no bearing on the quality of music that they released.

From ’60s punk to 143 Reade Street [home to Paradise Garage in New York City], the garage is a special place in music history, a refuge of authenticity. What’s the truth and what is myth? Will the garage forever be betrayed by success?

It depends how you gauge success. The garage is the natural breeding ground for all fledging bands. It’s generally when bands move out of the garage that they lose some of the magic. I’ve always preferred listening to the underdogs than a bunch of fancy dans.

Does it even matter what music you perform when you stand for certain ethics? Could the garage be located within any music?

Obviously, ethics are extremely personal and subjective. There’s only two forms of music that exist: good and bad! We all make our own decisions based on our social existence. The garage is easily substituted for a bedroom studio these days. There should be no barriers to the creation of music.

The era of “Garageland” is always portrayed as one of musical open-mindedness where punk, soul and reggae could coexist without friction and feed on each other. Is that a myth, too?

I have many friends who cross genres and have done so from an early age. I try not to pigeonhole music these days because it limits what you can and can’t listen to. I used to be extremely militant with regards to music, but those days have gone and the barriers are down.

The Clash were always open to more music genres than punk. How would you rate their influence on club music?

The influence of Roland is far greater than anything that the Clash offered clubland. So in that sense, the Clash had little to no effect on dance music. “There’s twenty-two singers! But one microphone/Back in the garage./There’s five guitar players! But one guitar./Back in the garage./Complaints! Complaints! Wot an old bag./Back in the garage./All night.” The DIY attitude of that last verse on “Garageland” lives with me today. Who cares about your tools? My advice to anybody would be to just do it and don’t let barriers get in the way. Don’t make compromises and don’t let the bastards win.

Can you think of any true successors to the Clash and “Garageland” in particular? Is that spirit still alive somewhere?

I’m not sure about true successors to the Clash. Punk, for me, was the music of the streets while living in Scotland. It was when I moved to Manchester in 1983 that my musical tastes moved away from punk towards the merging sounds of electro and hip-hop. These sounds were all over Manchester and it seemed like a natural progression for me. Arguably, Public Enemy was the one act that offered new doors for learning and came with a power no other hip-hop act had at the time. For me they were the last important musical group in history. These days people tend to go with mediocracy, and we’ve allowed ourselves to be corrupted by the media and corporations. I feel for the youth of today because they don’t seem to have the get and go to make a statement against these injustices that we had.

Read previous Rewind interviews with Call Super, L’Estasi Dell’oro, Flemming Dalum and more, and read Finn Johannsen’s recommendations of Soichi Terada, Conrad Schnitzler and more here.

Photo by Adrian Boot

Published October 07, 2015.