Richard Brody recommends Claude Lanzmann’s The Patagonian Hare: A Memoir

People in America tend not to have seen Shoah for a very silly, practical reason: its unavailability on DVD. You can buy a copy from absolut MEDIEN, but very few people know that this version is code-free. So if you didn’t get a copy when the DVD was in circulation a decade ago, or if you weren’t an adult in the mid-eighties when Shoah was in theaters or on public television, you’re kind of out of luck. We’re talking here about a generation of Americans in their twenties and thirties that don’t even know what Shoah is. Of course, watching the film on YouTube is a literal option, but not an ideal one. I’ve certainly watched plenty of films on YouTube, and I also consider the website to be the cinematheque of the future. But Shoah is a grand-scale movie, and it gains a lot from being projected onto a large screen. Conversely, the smaller you see it, the more reducible it becomes to a mere delivery of information, and devoid of its—how should I put it?—unique beauty.

Beauty isn’t the opposite of horror—it’s the sublimation of horror. It’s the transcendental redemption of horror, but certainly not its absence. When you see the beauty of the Polish forests in Shoah, you realize that only the knowledge of what took place there actually despoils it. Visually speaking, there’s nothing left that evokes murder—a point also brilliantly made in the beginning of Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog. The killing fields, in their post-war state, reveal nothing. In comparison to Resnais, Claude Lanzmann raises the aesthetic risk in Shoah to an even higher level by bringing the actual survivors—his interview subjects—back to these places of indescribable pain and suffering. Simon Srebnik on the boat or in front of the church in Chełmno are images of theatrical daring stronger than any method. They carry with them incredible aesthetic risk and reinforce that what you’re seeing is, in many instances, drama—not a documentary, though entirely the truth. You don’t need to see piles of bodies to know that a colossal crime was committed. And if you do, you’re probably morally obtuse.

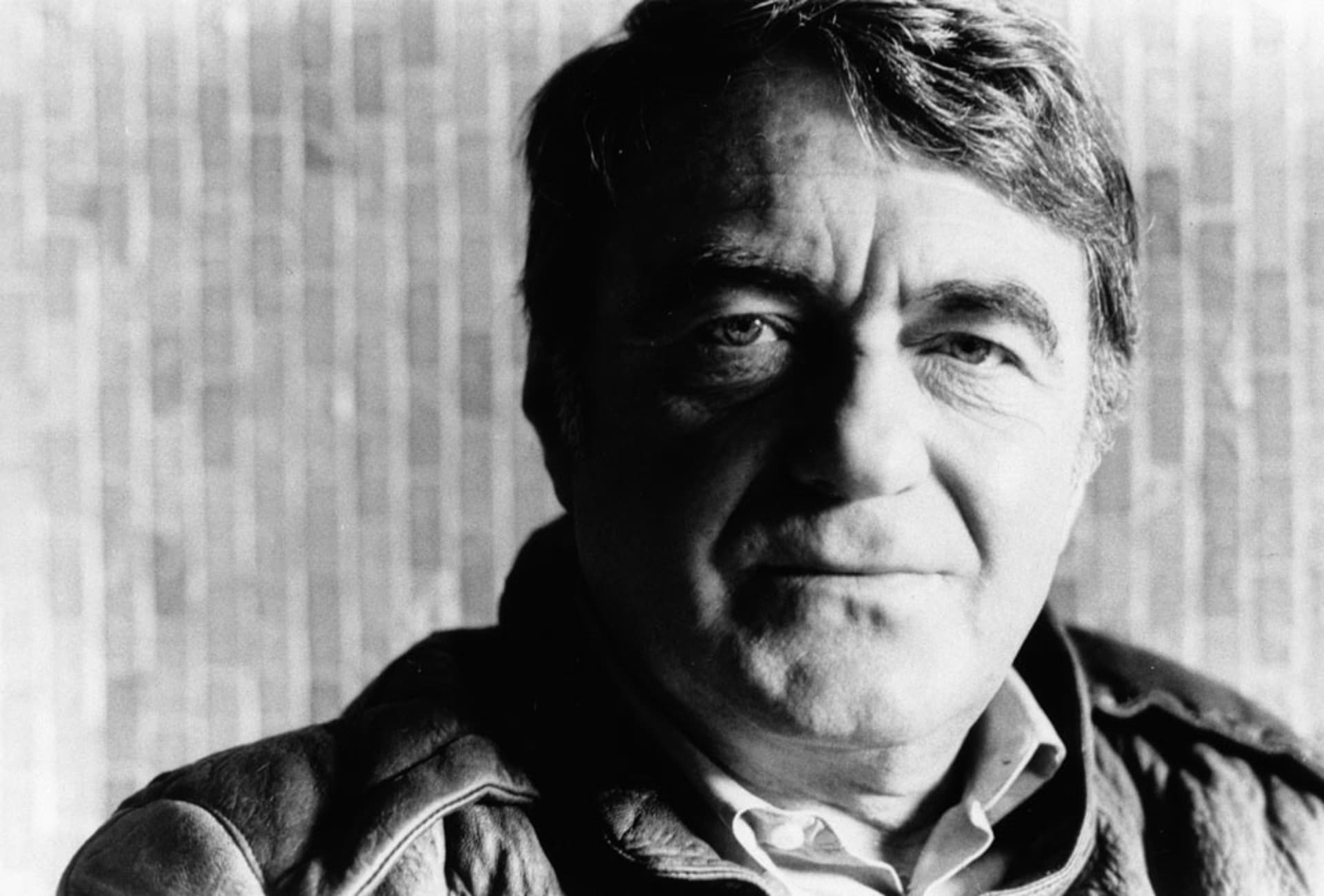

Every film and every book is actually two films, two books. There’s the work itself and then the making-of. Especially with non-fiction, where the author or director spends so much time travelling, interviewing, and researching. The experiences that go into the production can’t all be reflected in the results. Also, these experiences, even if related to events of complete horror, don’t have to be horrifying themselves. Lanzmann’s memoir, The Patagonian Hare, is often humorous, and that wasn’t shocking for me in the least. I was more blown away by the life he led overall. Before reading it, I knew next to nothing about Lanzmann’s biography, with only the vaguest awareness that he had been together with Simone de Beauvoir and was a friend of Jean-Paul Sartre. But I didn’t know of his adventurous nature; his involvement in the Resistance; his experiences of anti-Semitism in Paris in the thirties; his athleticism; that he would go out of his way to confront physical danger. I suspected he was a tough character because I had interviewed him in 2003 in Paris for my book about Jean-Luc Godard—who had proposed a joint film project to Lanzmann that was never realized. Lanzmann was very generous and it was a good discussion, but I found it very intimidating to talk to him. Lanzmann had an intensity in his gaze when he looked at me that seemed to contain a condensed and extraordinary strength, an amazing moral authority. It was like interviewing Moses.

After reading The Patagonian Hare, I realized this strength was built on experience, on the willingness to confront grave physical, emotional and moral danger. Lanzmann has lived his life running the risk of nonexistence, running the risk of death. The Patagonian Hare made clear that Shoah didn’t come out of nowhere. I had always wondered, “Who is this man who made this film in the middle of his life?” I felt as if I understood, because I myself didn’t write professionally until my forties, and Lanzmann didn’t complete his first film, Israel, Why until he was around forty-seven. Waiting that long to undertake his first big work is, in Lanzmann’s case, an incredible act of bravery—and he topped it by putting twelve years into Shoah, which he didn’t finish until he was almost sixty. Somebody with such an overflowing mind, soul, and energy being patient enough to wait to accomplish something so great, is nothing less than astounding.

At its core, Lanzmann explores in his memoirs the most basic question of his life: What does it mean to be a Jew? For him, the very idea of the survival of the Jewish people went hand in hand with the promise of resistance: the founding and endurance of Israel, the willingness of Ben-Gurion to fire on the Zionist paramilitary Irgun as they were bringing arms into the country for their own militia—these were integral parts of the promise of a Jewish future, the willingness of Israel to function like a state. The concept of resistance was also a main theme in the last part of Shoah and one that people don’t talk about very much. In fact, the film ends with the acknowledgement that Jews weren’t only passive victims, but also attempted to fight back as best they could. Or, to put it in Lanzmann’s terms, Jews attempted to “reappropriate violence”. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in Anti-Semite and Jew that Jewish identity is defined by the anti-Semite, without whom Jewish identity would be lost. After Lanzmann went to Israel for the first time in the fifties, he claimed to have found proof of the opposite. Indeed, his life and work are dedicated to fighting against Sartre’s definition. I’m not sure he’s been entirely successful, but The Patagonian Hare undoubtedly succeeds in exposing the paradox of his struggle. ~

Richard Brody is an author, staff writer and movie-listings editor for The New Yorker. His most recent book, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard, was published by Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company in 2009.

photo: © Medien GmbH, www.absolutmedien.de

This text appeared first in Electronic Beats Magazine N° 30 (Summer 2012). Read the full issue on issuu.com:

Published February 13, 2013. Words by Richard Brody.